Sun, May 5, 2024

[Archive]

Volume 21, Issue 4 (April 2023)

IJRM 2023, 21(4): 355-358 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Haghjoo A, Haghjoo R, Rahimipour M. Ovarian torsion in a 2-year-old girl: A case report. IJRM 2023; 21 (4) :355-358

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-2729-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-2729-en.html

1- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran.

2- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran.

3- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. , marziehrahimipour@yahoo.com

2- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran.

3- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. , marziehrahimipour@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 1615 kb]

(274 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (425 Views)

1. Introduction

Abnormal twisting of the fallopian tube and ovary around the ovarian pedicle results in ovarian torsion (1). In most cases, ovarian torsion occurs during the reproductive years, while idiopathic torsion is a relatively rare event within the pediatric age group (2). In children, adnexal torsion can occur at different ages, but > 52% of cases occur between the ages of 9 and 14, with an average of 11 yr. ovarian torsion is also rare in neonates. It occurs in 16% of girls < 1 yr (3, 4).

The signs and symptoms of ovarian torsion, like lower abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting, are usually nonspecific. Tenderness in the lower abdomen and sometimes a mass may be revealed by clinical examination. Differential diagnosis includes intussusception, infantile colic, appendicitis, acute gastroenteritis, constipation, mesenteric lymphadenitis, ureteric colic, and urinary tract infection (5).

Adnexal torsion is a clinical diagnosis. When the clinical features, patient history, and/or imaging are suspected of adnexal torsion, immediate exploratory surgery makes the final diagnosis. In the pediatric population, the best diagnostic and therapeutic approach is laparoscopic surgery. The persistence of pain for more than 10 hr is linked to an increased rate of tissue necrosis. So, fast diagnosis and operation can prevent irreversible adnexal damage, salvaging the adnexal torsion, and increasing the success of ovarian preservation (6-9). This clinical case report presented a 2-yr-old girl with left ovarian torsion as a rare case.

2. Case Presentation

The case is a 2-yr-old girl complaining of episodic lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days. Her parents visited the emergency room in Jahrom Motahari hospital, Jahrom, Iran and they were advised for further observation at home due to absence of any physical exam findings. However, since abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting (4 times) continued until the night, they visited the hospital again. At admission, she looked pale and lethargic with vital signs as follows: BP: 90/60, PR: 100, T: 36/5, RR: 24, O2 sat: 96%.

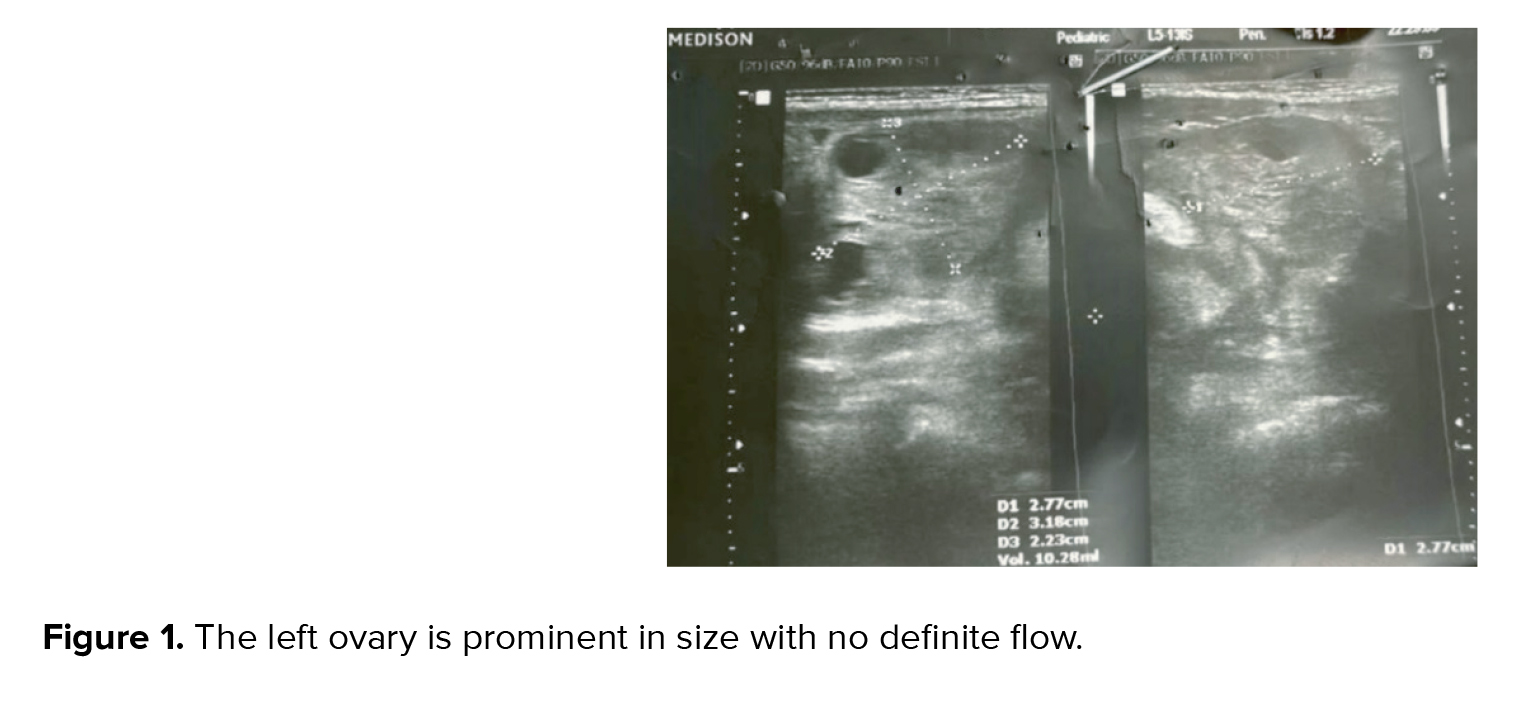

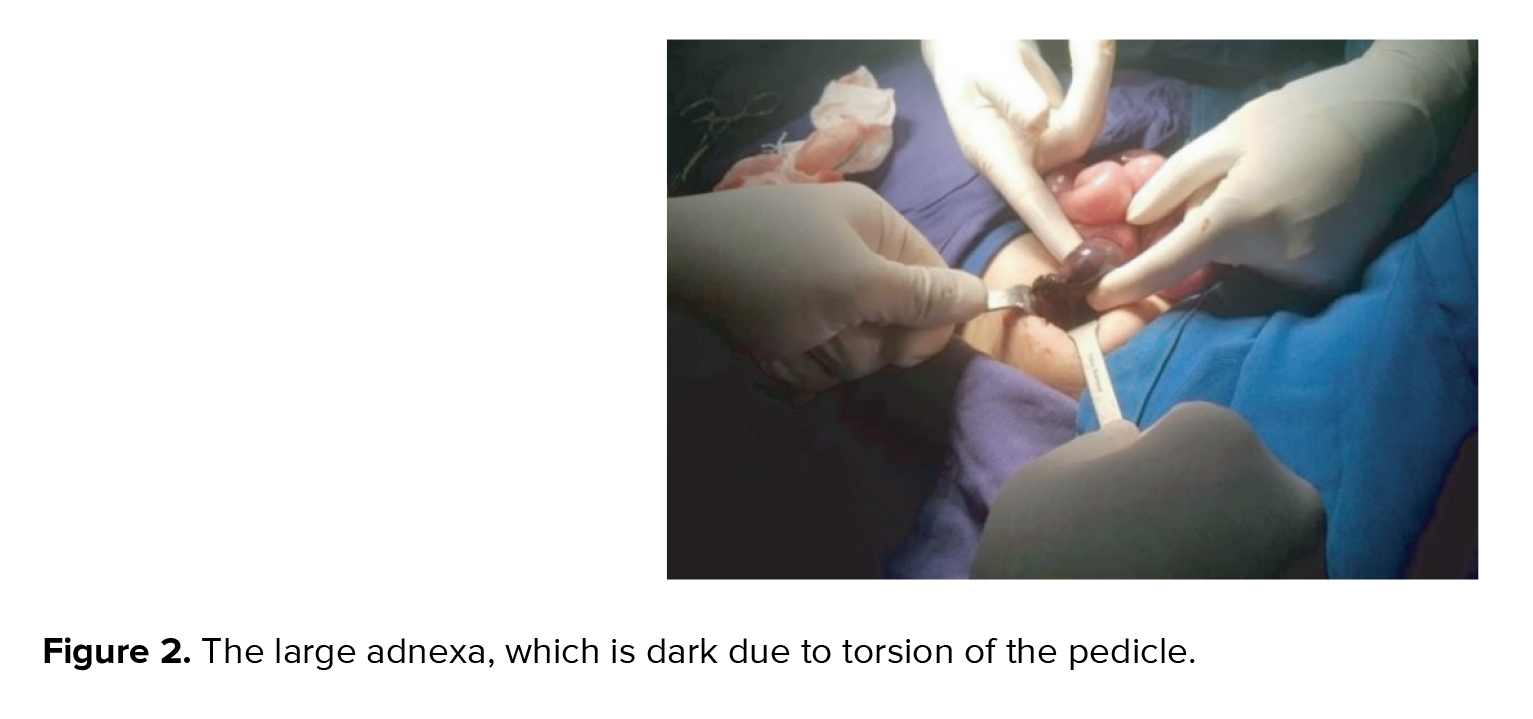

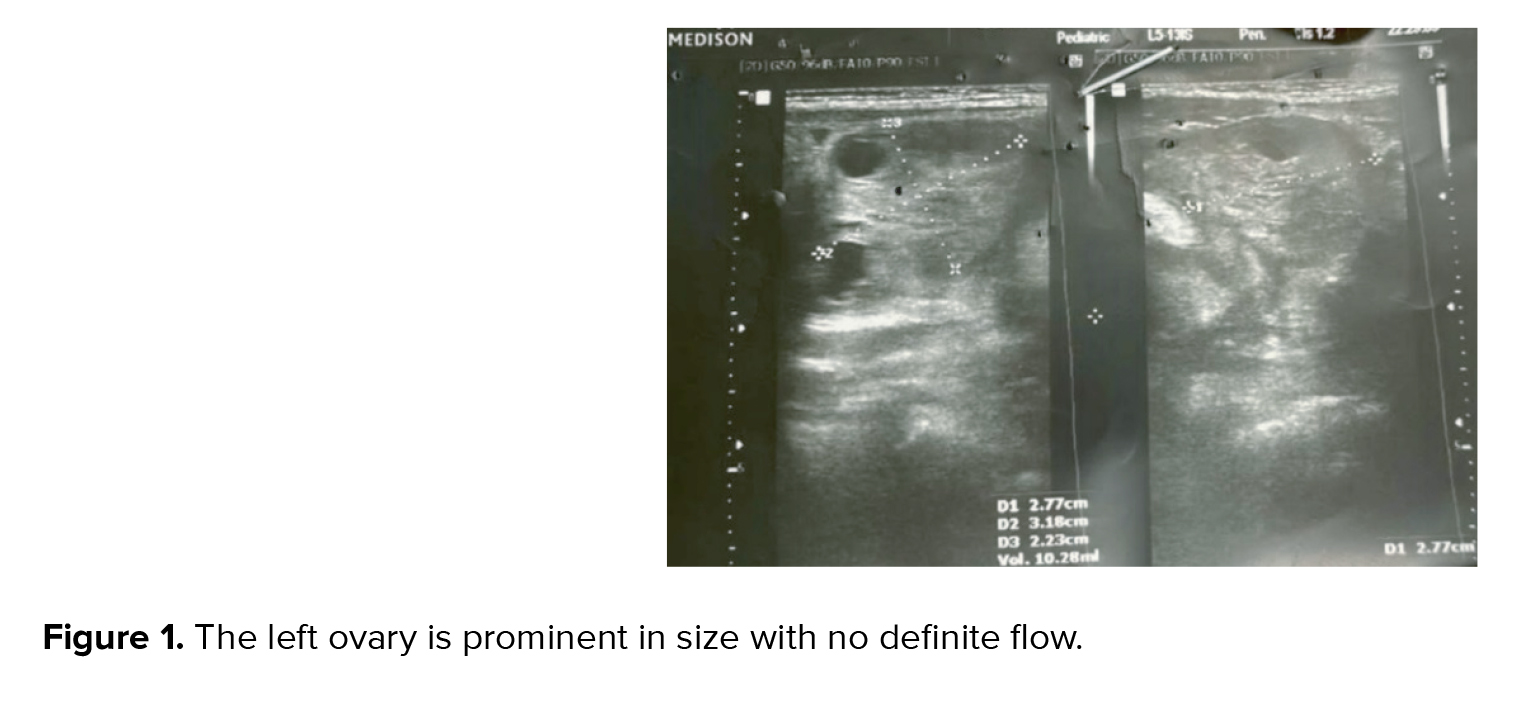

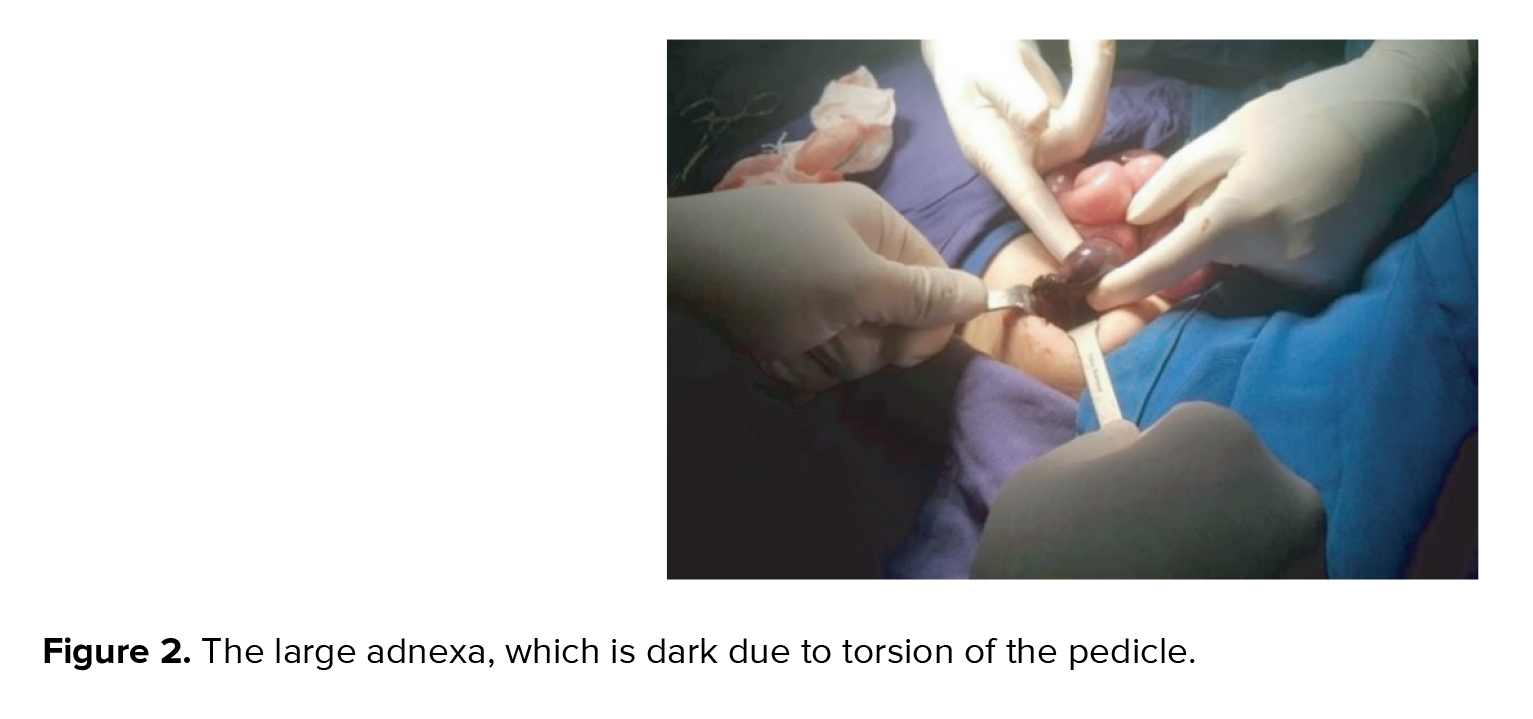

Her physical examination was normal except for mild tenderness in the lower abdomen with no palpable mass. Moreover, leukocytosis was noted in complete blood count. So, an urgent abdominopelvic ultrasound was performed, demonstrating a prominent left ovary size of 33×42 mm with no definite vascularity that was highly suspicious for ovarian torsion (Figure 1). No sonographic sign of intussusception and acute appendicitis were observed. Eventually, she underwent laparotomy due to ovarian torsion. A relatively complete torsion was observed in the left ovarian pedicle. Ovarian detorsion was done and decided to preserve the ovary even though the left ovary and fallopian tube had a dark appearance and 10-15% of the ovarian tissue was normal (Figure 2). After about 20 min, color of the ovary and fallopian tube returned to relatively normal, which indicated normal blood flow (Figure 3). The patient was discharged in stable condition 2 days after the surgery because the color Doppler ultrasound showed normal ovarian blood flow.

2.1. Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were maintained during this study, and written consent was taken from the patient's parents for this presentation.

3. Discussion

Ovarian torsion commonly occurs during childbearing age and postmenopausal age (5). It is estimated to be about 5 per 100,000 in females between 1 and 20 yr old (1). There are several risk factors associated with ovarian torsion, such as ovarian mass (especially dermoid) or cyst, previous torsion or surgery, polycystic ovary, tubal sterilization, and pregnancy (10, 11). In the pediatric patient, about 51-84% of adnexal torsions occur due to adnexal pathology, which mainly includes follicular or hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, cystic teratomas or dermoid, and less frequently cystadenomas, para ovarian cysts, and hydrosalpinx (8, 12).

Physical examination findings, such as normal temperature, low-grade fever, and/or mild tachycardia, are typically nonspecific to adnexal torsion. Acute pelvic or abdominal pain with variable duration (days to months) is the most common symptom, and it is often isolated to one side. Also, it can be mild or intense, non-radiating, constant, or intermittent (depending on whether the torsion is partial or complete). In addition, symptoms such as flank pain, nausea and vomiting due to peritoneal reflexes, and anorexia are usually associated with adnexal torsion. In patients with adnexal torsion, most laboratory findings are normal. However, a slight leukocytosis can sometimes occur (13). Lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, mild tenderness in the lower abdomen with no palpable mass, and leukocytosis were diagnosed in this patient.

Clinical diagnosis of ovarian torsion must be differentiated from hemorrhagic ovarian cyst rupture, appendicitis, gastroenteritis, and kidney stone (8, 13, 14). Moreover, adnexal torsion is often difficult to diagnose because of the vague and variable clinical signs and nonspecific imaging findings. To evaluate blood flow to the ovaries in pediatric and adolescent patients, pelvic ultrasonography with color Doppler is the common and accurate diagnostic imaging of adnexal torsion (14, 15). Therefore, ultrasonography is usually enough for diagnosis (5).

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not the first-line imaging modalities in adnexal torsion, but they can be used to assess the structure if ultrasound is not available or if the differential diagnosis remains with other cases such as appendicitis (14). Delay in diagnosis of ovarian torsion commonly leads to loss of the involved ovary and other complications (5).

Ovarian torsion can be treated with detorsion or oophorectomy. Detorsion is a safe and effective treatment for ovarian torsion, and it may be more optimal for all premenopausal women because of the high rates of ovarian preservation and low risk of complications (16). Recent evaluation of pediatric patients in the national inpatient sample showed that 15%, 6%, and 78% of cases underwent detorsion, detorsion with oophoropexy, and oophorectomy alone, respectively (17). Another case report presented ovarian torsion and histopathological disorders, including cystic lesions with extensive calcification in a 4-month-old baby undergoing oophorectomy (5).

Although ovarian torsion is rare in children, early diagnosis is critical because it can save the ovary and prevent psychological trauma to the parents and child. Therefore, the possibility of ovarian torsion must be considered in all female infants with suspicious abdominal pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Dr. Amir Hossein Pourdavoud (general surgeon), Dr. Reza Sahraei (anesthesiologist), and the operating room staff of Jahrom Motahari hospital, Jahrom, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Full-Text: (64 Views)

1. Introduction

Abnormal twisting of the fallopian tube and ovary around the ovarian pedicle results in ovarian torsion (1). In most cases, ovarian torsion occurs during the reproductive years, while idiopathic torsion is a relatively rare event within the pediatric age group (2). In children, adnexal torsion can occur at different ages, but > 52% of cases occur between the ages of 9 and 14, with an average of 11 yr. ovarian torsion is also rare in neonates. It occurs in 16% of girls < 1 yr (3, 4).

The signs and symptoms of ovarian torsion, like lower abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting, are usually nonspecific. Tenderness in the lower abdomen and sometimes a mass may be revealed by clinical examination. Differential diagnosis includes intussusception, infantile colic, appendicitis, acute gastroenteritis, constipation, mesenteric lymphadenitis, ureteric colic, and urinary tract infection (5).

Adnexal torsion is a clinical diagnosis. When the clinical features, patient history, and/or imaging are suspected of adnexal torsion, immediate exploratory surgery makes the final diagnosis. In the pediatric population, the best diagnostic and therapeutic approach is laparoscopic surgery. The persistence of pain for more than 10 hr is linked to an increased rate of tissue necrosis. So, fast diagnosis and operation can prevent irreversible adnexal damage, salvaging the adnexal torsion, and increasing the success of ovarian preservation (6-9). This clinical case report presented a 2-yr-old girl with left ovarian torsion as a rare case.

2. Case Presentation

The case is a 2-yr-old girl complaining of episodic lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days. Her parents visited the emergency room in Jahrom Motahari hospital, Jahrom, Iran and they were advised for further observation at home due to absence of any physical exam findings. However, since abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting (4 times) continued until the night, they visited the hospital again. At admission, she looked pale and lethargic with vital signs as follows: BP: 90/60, PR: 100, T: 36/5, RR: 24, O2 sat: 96%.

Her physical examination was normal except for mild tenderness in the lower abdomen with no palpable mass. Moreover, leukocytosis was noted in complete blood count. So, an urgent abdominopelvic ultrasound was performed, demonstrating a prominent left ovary size of 33×42 mm with no definite vascularity that was highly suspicious for ovarian torsion (Figure 1). No sonographic sign of intussusception and acute appendicitis were observed. Eventually, she underwent laparotomy due to ovarian torsion. A relatively complete torsion was observed in the left ovarian pedicle. Ovarian detorsion was done and decided to preserve the ovary even though the left ovary and fallopian tube had a dark appearance and 10-15% of the ovarian tissue was normal (Figure 2). After about 20 min, color of the ovary and fallopian tube returned to relatively normal, which indicated normal blood flow (Figure 3). The patient was discharged in stable condition 2 days after the surgery because the color Doppler ultrasound showed normal ovarian blood flow.

2.1. Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were maintained during this study, and written consent was taken from the patient's parents for this presentation.

3. Discussion

Ovarian torsion commonly occurs during childbearing age and postmenopausal age (5). It is estimated to be about 5 per 100,000 in females between 1 and 20 yr old (1). There are several risk factors associated with ovarian torsion, such as ovarian mass (especially dermoid) or cyst, previous torsion or surgery, polycystic ovary, tubal sterilization, and pregnancy (10, 11). In the pediatric patient, about 51-84% of adnexal torsions occur due to adnexal pathology, which mainly includes follicular or hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, cystic teratomas or dermoid, and less frequently cystadenomas, para ovarian cysts, and hydrosalpinx (8, 12).

Physical examination findings, such as normal temperature, low-grade fever, and/or mild tachycardia, are typically nonspecific to adnexal torsion. Acute pelvic or abdominal pain with variable duration (days to months) is the most common symptom, and it is often isolated to one side. Also, it can be mild or intense, non-radiating, constant, or intermittent (depending on whether the torsion is partial or complete). In addition, symptoms such as flank pain, nausea and vomiting due to peritoneal reflexes, and anorexia are usually associated with adnexal torsion. In patients with adnexal torsion, most laboratory findings are normal. However, a slight leukocytosis can sometimes occur (13). Lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, mild tenderness in the lower abdomen with no palpable mass, and leukocytosis were diagnosed in this patient.

Clinical diagnosis of ovarian torsion must be differentiated from hemorrhagic ovarian cyst rupture, appendicitis, gastroenteritis, and kidney stone (8, 13, 14). Moreover, adnexal torsion is often difficult to diagnose because of the vague and variable clinical signs and nonspecific imaging findings. To evaluate blood flow to the ovaries in pediatric and adolescent patients, pelvic ultrasonography with color Doppler is the common and accurate diagnostic imaging of adnexal torsion (14, 15). Therefore, ultrasonography is usually enough for diagnosis (5).

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not the first-line imaging modalities in adnexal torsion, but they can be used to assess the structure if ultrasound is not available or if the differential diagnosis remains with other cases such as appendicitis (14). Delay in diagnosis of ovarian torsion commonly leads to loss of the involved ovary and other complications (5).

Ovarian torsion can be treated with detorsion or oophorectomy. Detorsion is a safe and effective treatment for ovarian torsion, and it may be more optimal for all premenopausal women because of the high rates of ovarian preservation and low risk of complications (16). Recent evaluation of pediatric patients in the national inpatient sample showed that 15%, 6%, and 78% of cases underwent detorsion, detorsion with oophoropexy, and oophorectomy alone, respectively (17). Another case report presented ovarian torsion and histopathological disorders, including cystic lesions with extensive calcification in a 4-month-old baby undergoing oophorectomy (5).

Although ovarian torsion is rare in children, early diagnosis is critical because it can save the ovary and prevent psychological trauma to the parents and child. Therefore, the possibility of ovarian torsion must be considered in all female infants with suspicious abdominal pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Dr. Amir Hossein Pourdavoud (general surgeon), Dr. Reza Sahraei (anesthesiologist), and the operating room staff of Jahrom Motahari hospital, Jahrom, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Type of Study: Case Report |

Subject:

Reproductive Surgery

References

1. Tsai J, Lai J-Y, Lin Y-H, Tsai M-H, Yeh P-J, Chen C-L, et al. Characteristics and risk factors for ischemic ovary torsion in children. Children 2022; 9: 206. [DOI:10.3390/children9020206] [PMID] [PMCID]

2. Tielli A, Scala A, Alison M, Vo Chieu VD, Farkas N, Titomanlio L, et al. Ovarian torsion: Diagnosis, surgery, and fertility preservation in the pediatric population. Eur J Pediatr 2022; 181: 1405-1411. [DOI:10.1007/s00431-021-04352-0] [PMID]

3. Sriram R, Zameer MM, Vinay C, Giridhar BS. Black ovary: Our experience with oophoropexy in all cases of pediatric ovarian torsion and review of relevant literature. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2022; 27: 558-560.

4. Sosnowska-Sienkiewicz P, Mankowski P. Profile of girls with adnexal torsion: Single center experience. Indian Pediatr 2022; 59: 293-295. [DOI:10.1007/s13312-022-2494-5] [PMID]

5. Karambelkar RP, Shah S, Deshpande N, Singh D. Ovarian torsion in a 4-month-old baby. Pediatric Oncall 2013; 10: 60. [DOI:10.7199/ped.oncall.2013.21]

6. Sheizaf B, Ohana E, Weintraub AY. "Habitual Adnexal Torsions"-recurrence after two oophoropexies in a prepubertal girl: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013; 26: e81-e84. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.01.060] [PMID]

7. Yildiz A, Erginel B, Akin M, Karadağ CA, Sever N, Tanik C, et al. A retrospective review of the adnexal outcome after detorsion in premenarchal girls. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2014; 11: 304-307. [DOI:10.4103/0189-6725.143134] [PMID]

8. Geimanaite L, Trainavicius K. Ovarian torsion in children: Management and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48: 1946-1953. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.04.026] [PMID]

9. Casey RK, Damle LF, Gomez-Lobo V. Isolated fallopian tube torsion in pediatric and adolescent females: A retrospective review of 15 cases at a single institution. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013; 26: 189-192. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.02.010] [PMID]

10. Bridwell RE, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Ovarian torsion. Am J Emerg Med 2022; 56: 145-150. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.046] [PMID]

11. Gupta A, Gadipudi A, Nayak D. A five-year review of ovarian torsion cases: Lessons learnt. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2020; 70: 220-224. [DOI:10.1007/s13224-020-01319-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Focseneanu MA, Omurtag K, Ratts VS, Merritt DF. The auto-amputated adnexa: A review of findings in a pediatric population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013; 26: 305-313. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpag.2012.08.012] [PMID]

13. Sasaki KJ, Miller CE. Adnexal torsion: Review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014; 21: 196-202. [DOI:10.1016/j.jmig.2013.09.010] [PMID]

14. Gounder S, Strudwick M. Multimodality imaging review for suspected ovarian torsion cases in children. Radiography 2021; 27: 236-242. [DOI:10.1016/j.radi.2020.07.006] [PMID]

15. Naiditch JA, Barsness KA. The positive and negative predictive value of transabdominal color Doppler ultrasound for diagnosing ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48: 1283-1287. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.024] [PMID]

16. Ke K, Conrad DH, Cario GM. Conservative management of ovarian torsion. Gynecol Obstet 2020; 10: 543.

17. Sola R, Wormer BA, Walters AL, Heniford BT, Schulman AM. National trends in the surgical treatment of ovarian torsion in children: An analysis of 2041 pediatric patients utilizing the nationwide inpatient sample. Am Surg 2015; 81: 844-848. [DOI:10.1177/000313481508100914] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |