Tue, Feb 3, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 22, Issue 3 (March 2024)

IJRM 2024, 22(3): 235-244 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zare Moghaddam M, Zare F, Sandoghsaz R, Khalil A, Shams A. Human Vα7.2-Jα33 mucosal-associated invariant T cells in endometrial ectopic tissues tend to produce interferon-gamma: A new player in endometriosis etiology: A case-control study. IJRM 2024; 22 (3) :235-244

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3216-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3216-en.html

1- Department of Immunology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Reproductive Immunology Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Abortion Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

4- Department of Pediatrics, Shahid Sadoughi Hospital, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Department of Immunology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,alis743@yahoo.com

2- Reproductive Immunology Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Abortion Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

4- Department of Pediatrics, Shahid Sadoughi Hospital, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Department of Immunology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 1111 kb]

(994 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (939 Views)

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by endometrium-like tissue proliferation and development outside the uterus. The main symptoms of the condition are pain, infertility, adenomyosis, inflammation, and alterations in the placentation (1). "Endometriosis affects 10-15% of all women of reproductive age and 70% of women with chronic pelvic pain" (2). Despite several investigations, many concerns about endometriosis pathogenesis remain unanswered. Endometriosis is caused by a combination of variables, including genetics, immunological and hormonal characteristics, and prostaglandin metabolism (3).

Previous research has found alterations in the frequency and function of immune cells in endometriosis participants' peripheral blood, peritoneal fluid, and endometriotic tissue, which supports the involvement of immune responses in this disease (4). Although endometriosis is an inflammatory disease, immune-suppressing cells like M2 macrophages (type 2 macrophage), regulatory T cells, helper T cells type 2, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as well as related cytokines like interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming growth factor beta, have all been linked to disease progression (5-7). Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are a type of T cell with a non-variable alpha chain receptor known as Vα7.2-Jα33 and a limited diversity beta chain restricted to a non-polymorphic major histocompatibility complex I known as MR-1 in humans. These cells have a variety of surface markers, including CD3, CD25, CD8αα, CCR25, CCR6, CCR9, and CXCR6, CD122, CD95, CD69, CD27, and CD161, and their number varies according to the tissue. Their prevalence in the liver and the intestinal lamina propria is 20-50% and 1-10%, respectively. MAIT cells in humans are activated by the specific identification of bacterial and fungal antigens (including vitamin B2 and B9 metabolites) on MR-1 molecules. MAIT cells also express IL-18 and IL-12R permanently, resulting in cell activation by IL-12 or IL-18 (8). According to recent findings, MAIT cells have a role in mucosal immune response and the maintenance of lung and gut mucosal tissues. Bister and colleagues demonstrated that MAIT cells persist in the endometrium and decidua, resulting in powerful defense responses against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Furthermore, the existence of MAIT cells in vaginal mucous and their function are allegedly dependent on Th17 and the IL-17/IL-22 axis. MAIT cell frequency rises in infected and inflamed tissues, either by blood movement or local proliferation at infected locations (9-12).

Most findings have supported enhanced inflammation in ectopic lesions, although there is very little information on MAIT cells in the development of inflammation in endometriosis lesions, as well as the cells' potential to produce IL-17, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in the tissues. Given the importance of MAIT cells in mucosa-dependent immunity and lack of understanding of their role in endometriosis, this study intends to evaluate the cells role in the illness. This study aims to gain more knowledge in the field of MAIT cells in mucosal immune defense, the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases as well as cancer, as well as the lack of sufficient information about the role of this innate immune cell in endometriosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant population

Sample collection for this case-control study was performed in Obstetrics and Gynecology Departments of Shahid Sadoughi hospitals and sample analysis was conducted in Reproductive Immunology Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran from May 2021 to September 2022. 20 endometriosis women with stage III, IV were discernment through laparoscopy and 20 eutopic and ectopic tissue was prepared. As a control group, 20 healthy women who underwent laparoscopy for diagnostic reasons, tubal disconnection, ovarian cystectomy, ovarian drilling were included in the study. Women who had previously received hormonal medications, immunosuppressive drugs, or had a history of autoimmune, cancer, or infectious disorders were excluded from participating in the research. Before the start of the study, all participants were asked to fill out an informed consent form.

2.2. Gene expression in endometriotic tissue

2.2.1. Samples collection

The specimen tissues that were resected by laparoscopy method were 50-100 mg, they were later frozen in the RNA solution and were kept at -80°C until extraction of mRNA to preserve their RNA stability.

2.2.2. mRNA extractions

Homogenization was carried out using a sterile syringe and needle. Cell and tissue lysates were passed through a 20-gauge (0.9 mm) needle at least 5-10 times. TRIPURE Isolation Reagent kit )Gene-Foci, Switzerland( was used for RNA extraction and this process was carried out according to the kit instructions. Concentration, purity, and quality of extracted RNA were defined using spectrophotometric analysis (Thermo Fisher NanoDrop). All the disposal equipment used during the RNA extraction process was RNAase free.

2.2.3. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method

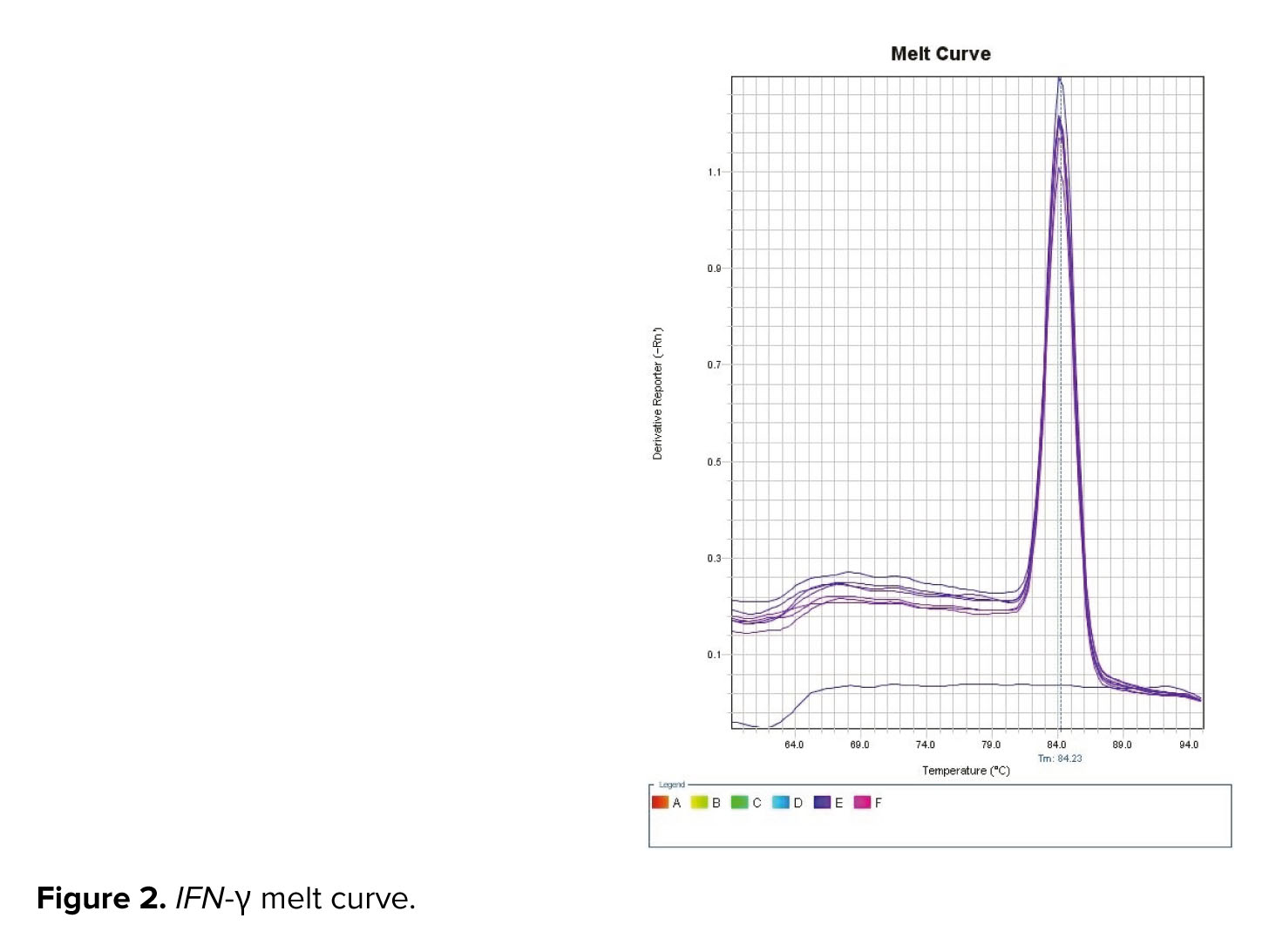

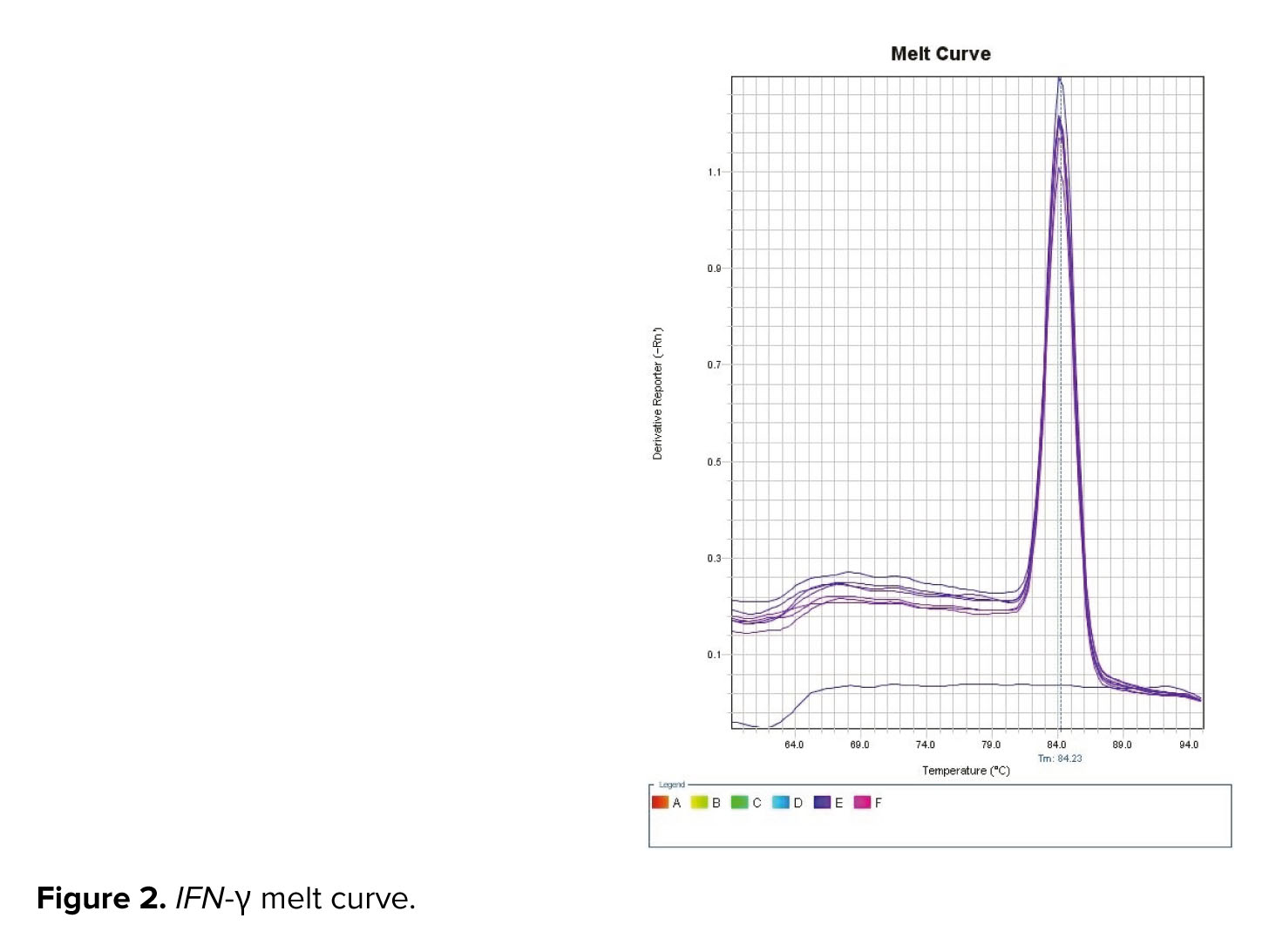

cDNA was synthesized of template mRNA according to the kit's instructions. The PCR reactions were carried out in a 20 µl total mixture volume including: 500 ng RNA, 10 µL buffer-mix (2x), 2 µl enzyme, and 8 µl of DEPC-treated. PCRs cycles were started by incubating the mixture for 4 min at 95oC, followed by 35 cycles composed of 94oC for 30 sec, 57oC for 30 sec, 72oC for 30 sec, and 72oC for 5 min and product size was confirmed on 1% agarose gel.

2.2.4. Quantitative real-time PCR method

The SYBER green PCR master mix was used in accordance with the kit protocol, and the mRNA expression levels were evaluated using the ABI/PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). Thermal cycling settings included 5 min at 95oC, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95oC, 60 sec at 61oC, and 45 sec at 72oC. Beacon designer 7.9 software was used to design specific primers for amplification of desired genes in the form of exon junction (in this method, one of the primers is designed exactly on the junction of exons) and intron inclusion (in this method, an intron with a length of at least 300 bp was performed). Table I provided the primer Vα7.2-Jα33 (13).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the studied subjects

In this study, the average age and weight of women in the control group were 41 yr and 71 kg, respectively, while of those in the patient group were 35 yr and 64 kg, respectively.

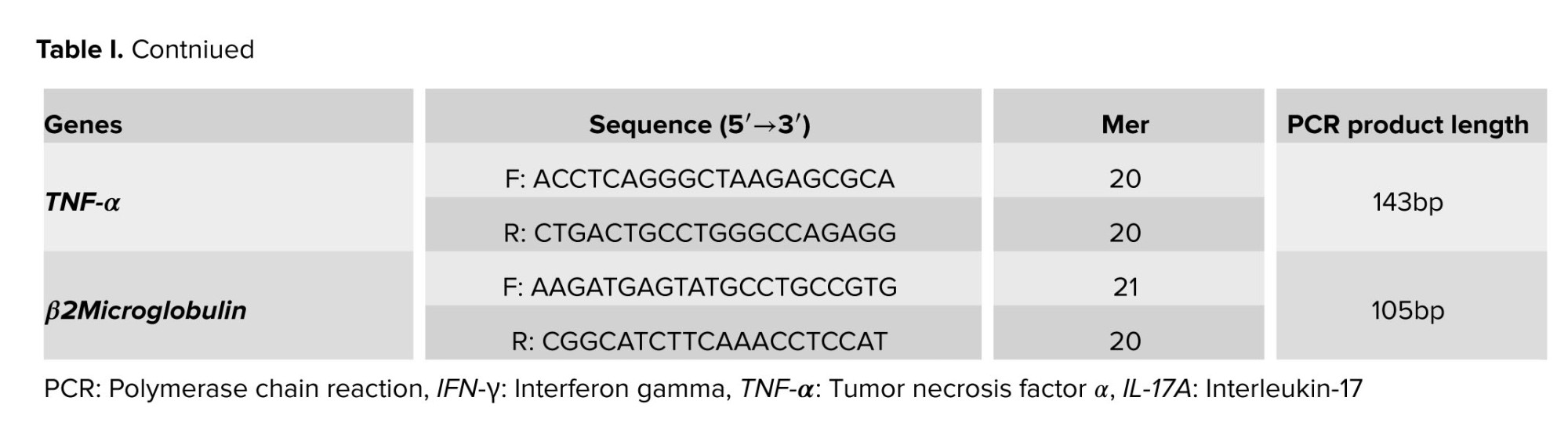

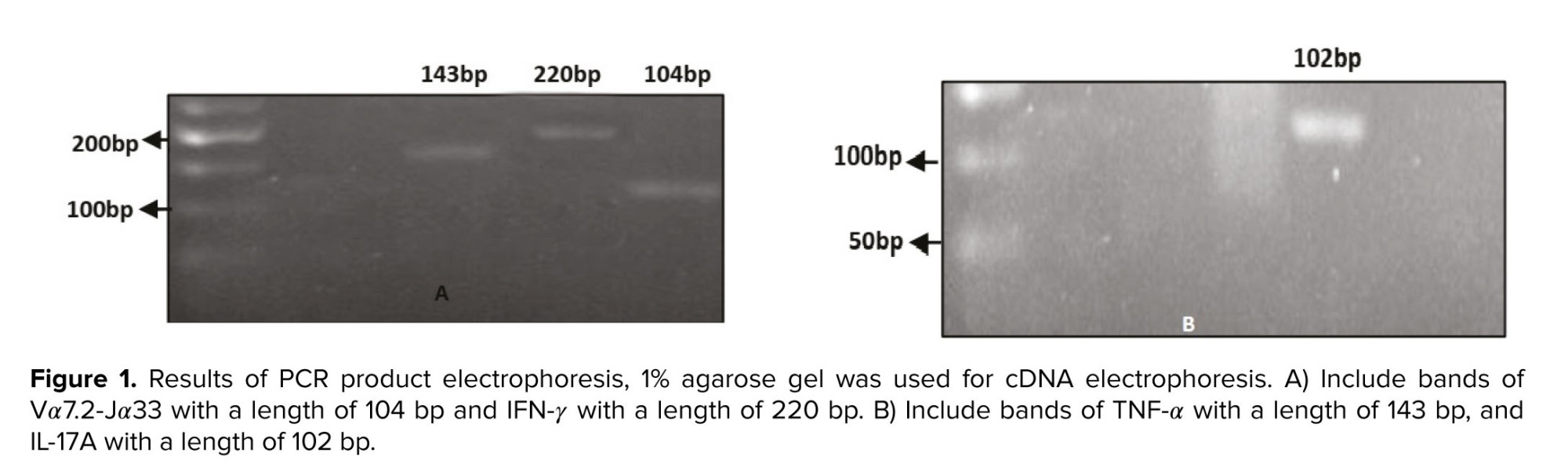

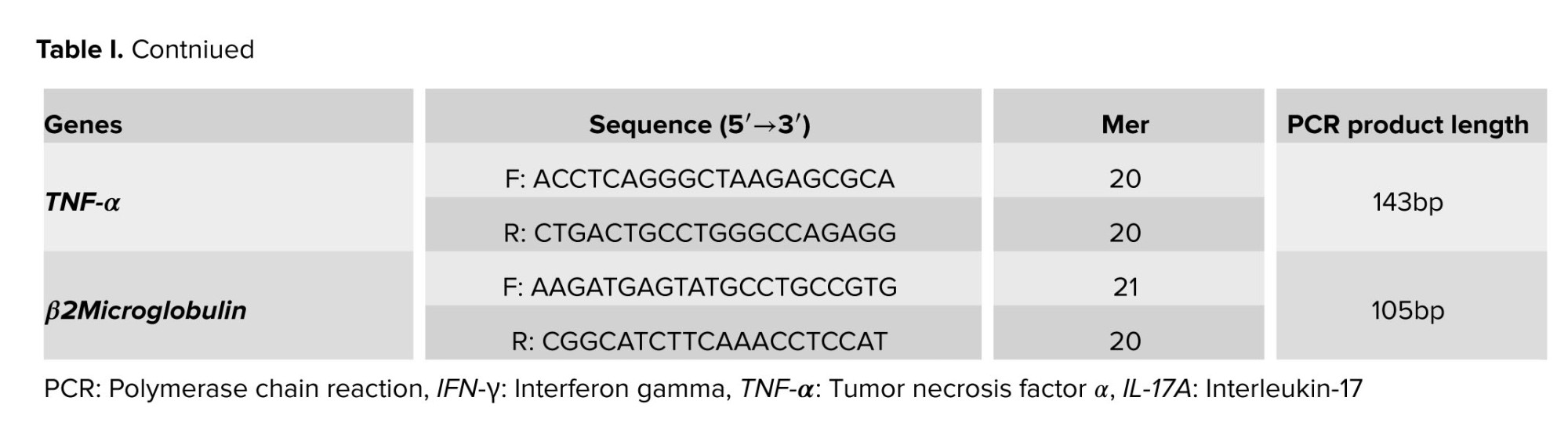

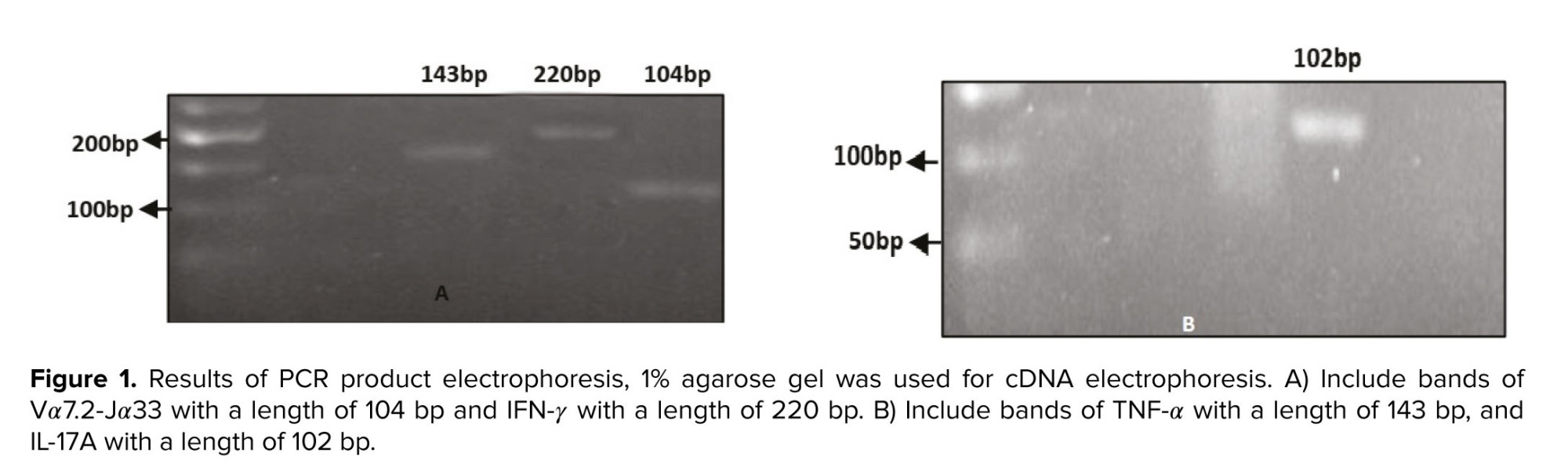

3.2. Quality control results of synthesized cDNA

The electrophoresis technique was used to assess the quality of the cDNA produced. Following cDNA synthesis, cDNA-containing samples were run on an agarose gel, yielding bands Vα7.2-Jα33 with a length of 104 bp, IFN-γ with a length of 220 bp, TNF-α with a length of 143 bp, IL-17A with a length of 102 bp (Figure 1), and melt curve of IFN-γ was observed in figure 2.

3.3. Real-time PCR results

3.3.1. Comparison of IFN-γ gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

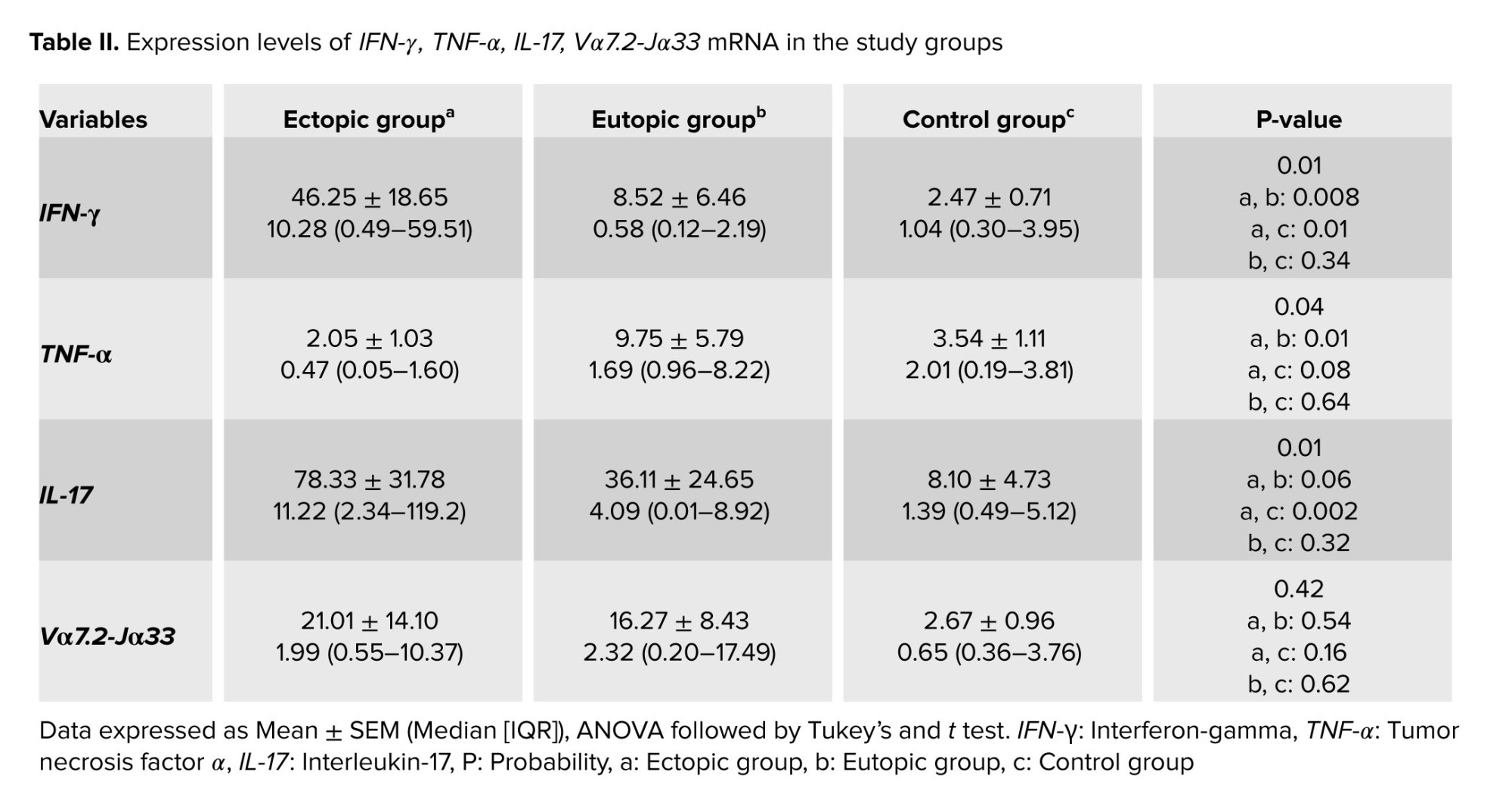

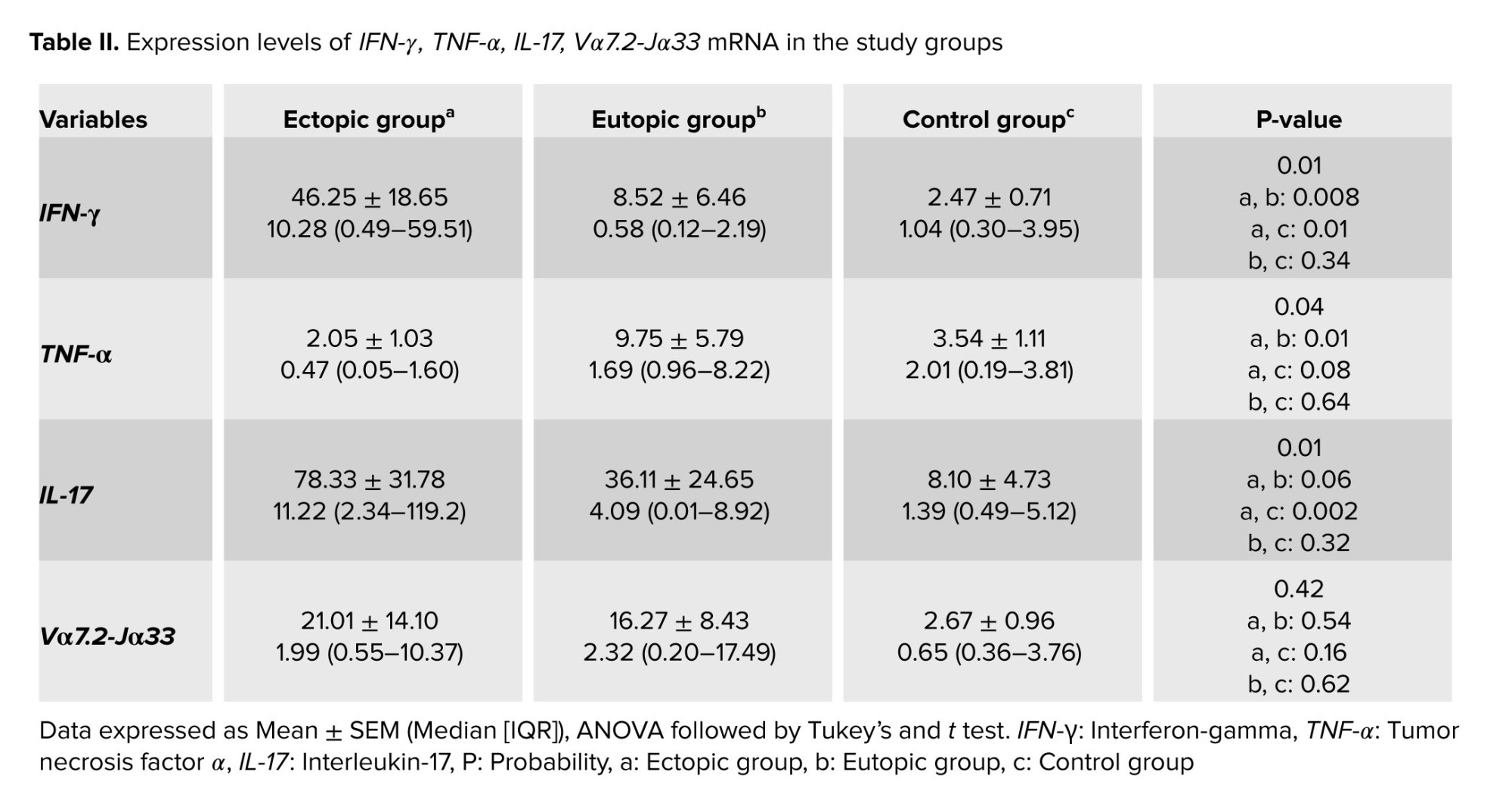

Table II shows that the expression of IFN-γ in ectopic tissue was significantly higher than in eutopic endometrium and normal endometrium, with p = 0.008 and p = 0.01 respectively. Furthermore, the expression of this gene in eutopic tissue does not differ significantly from the control group (Table II, Figure 3).

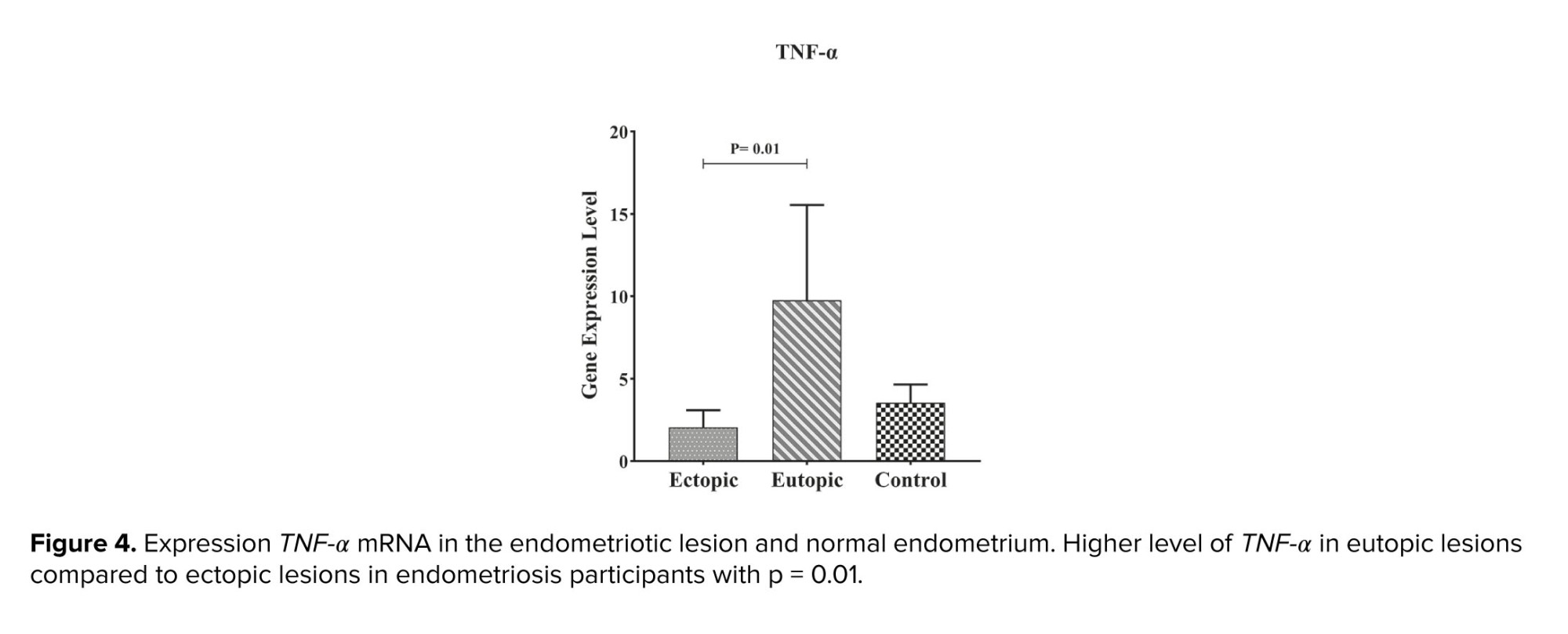

3.3.2. Comparison of TNF-α gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

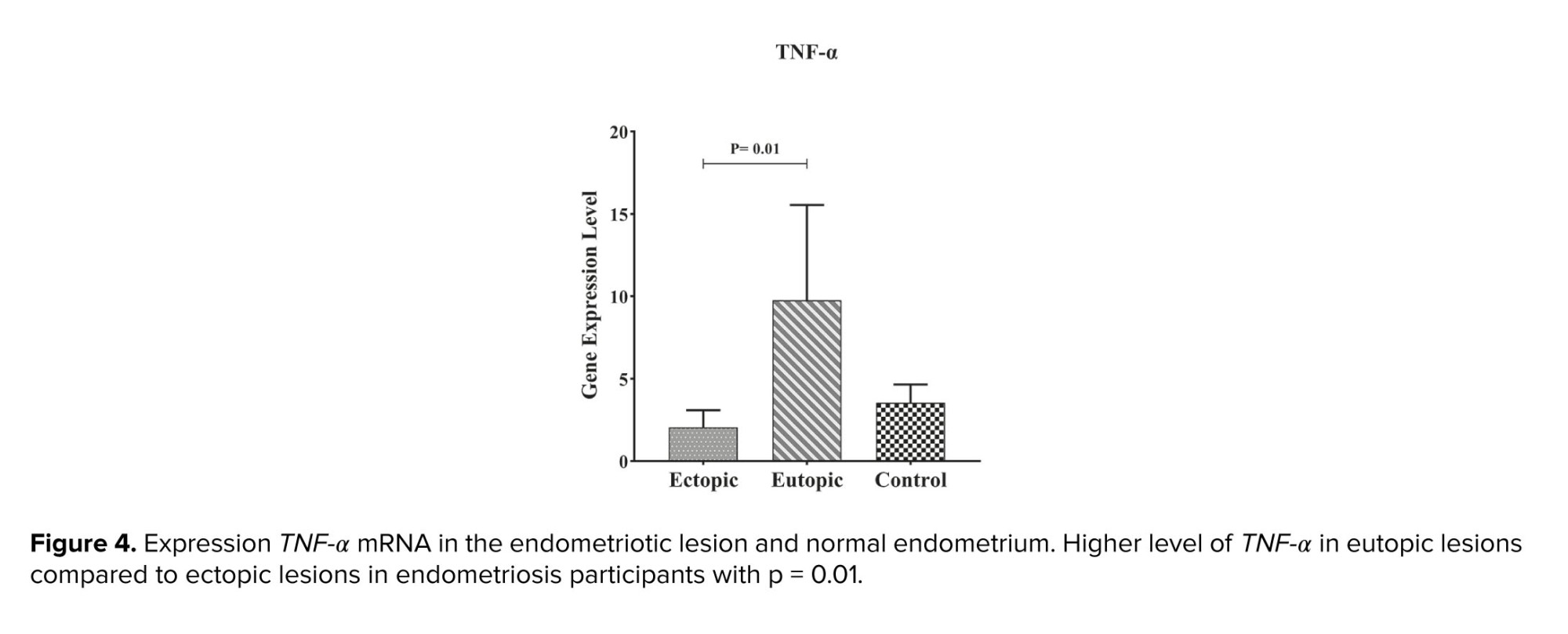

As shown in figure 3, the expression of TNF-α in eutopic tissue was significantly higher than in ectopic tissue with p = 0.01 (Table II, Figure 4).

3.3.3. Comparison of IL-17A gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

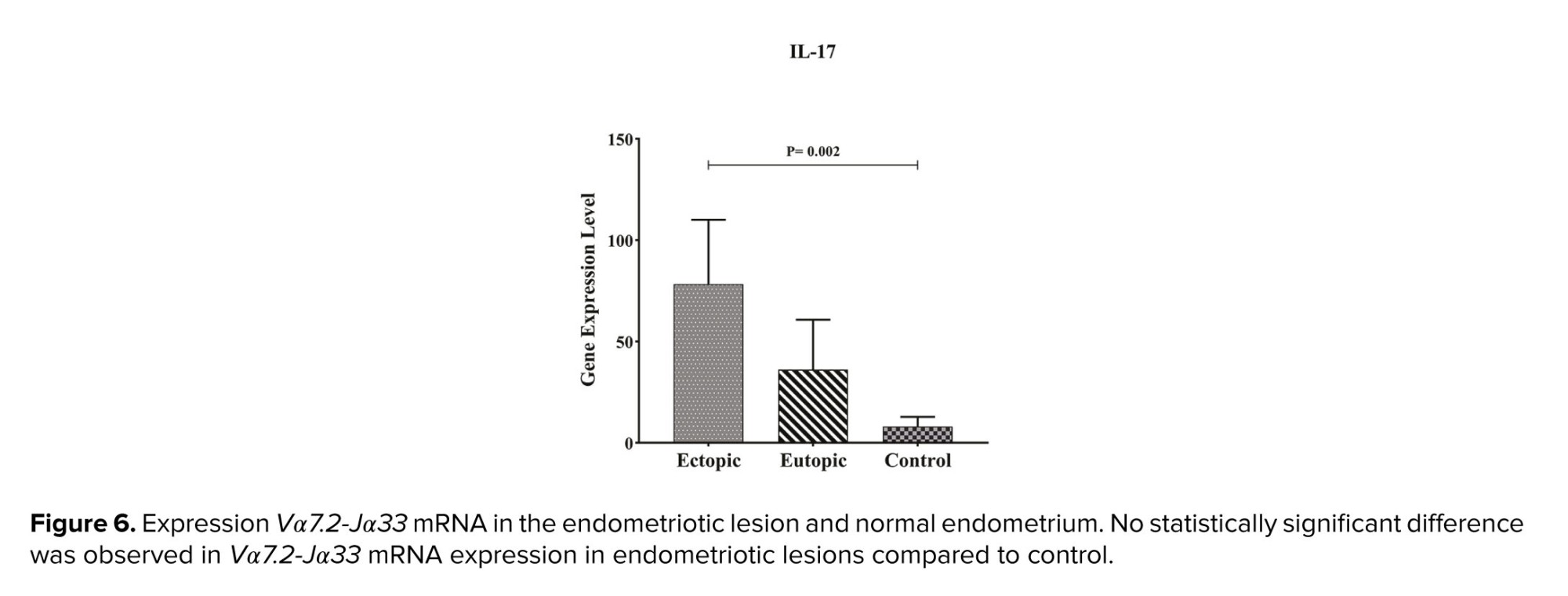

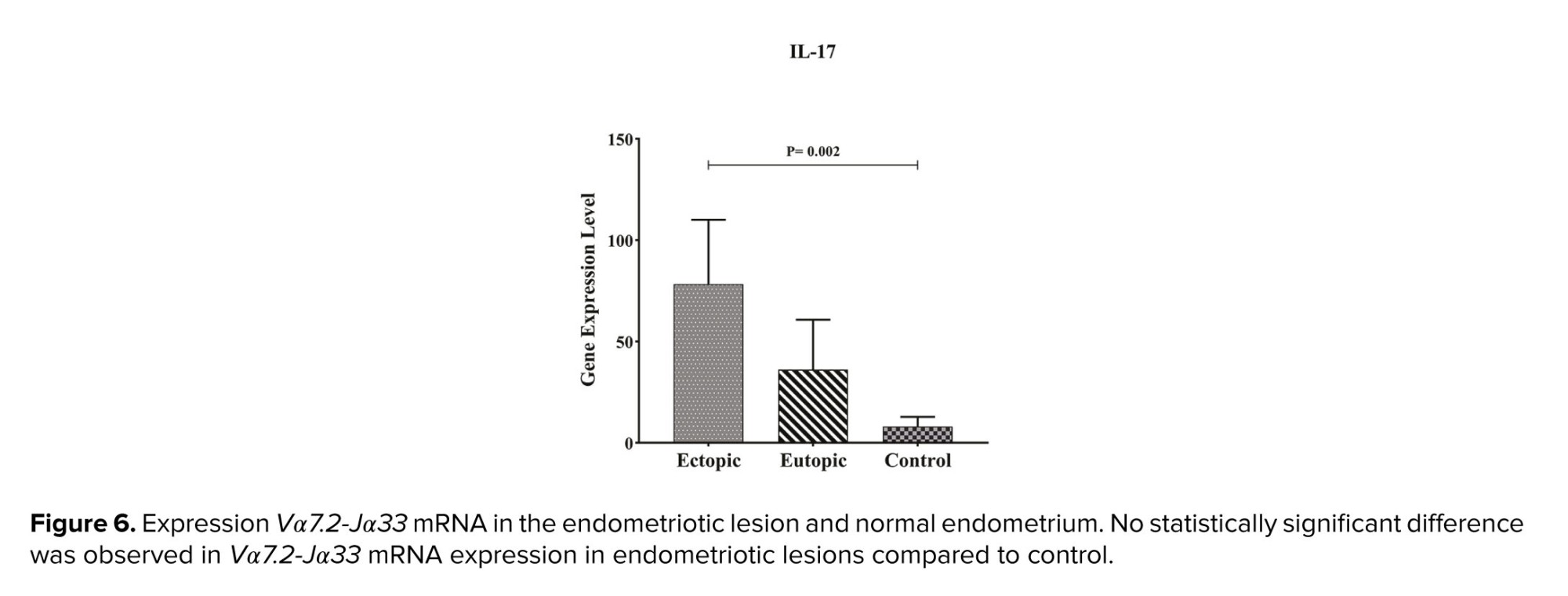

Our results demonstrated that IL-17A expression in ectopic tissue was considerably higher than in eutopic and control groups, with p = 0.002 (Table II, Figure 5).

3.3.4. The results of examining the expression of Vα7.2 Jα33 gene in ectopic, eutopic, and control tissue

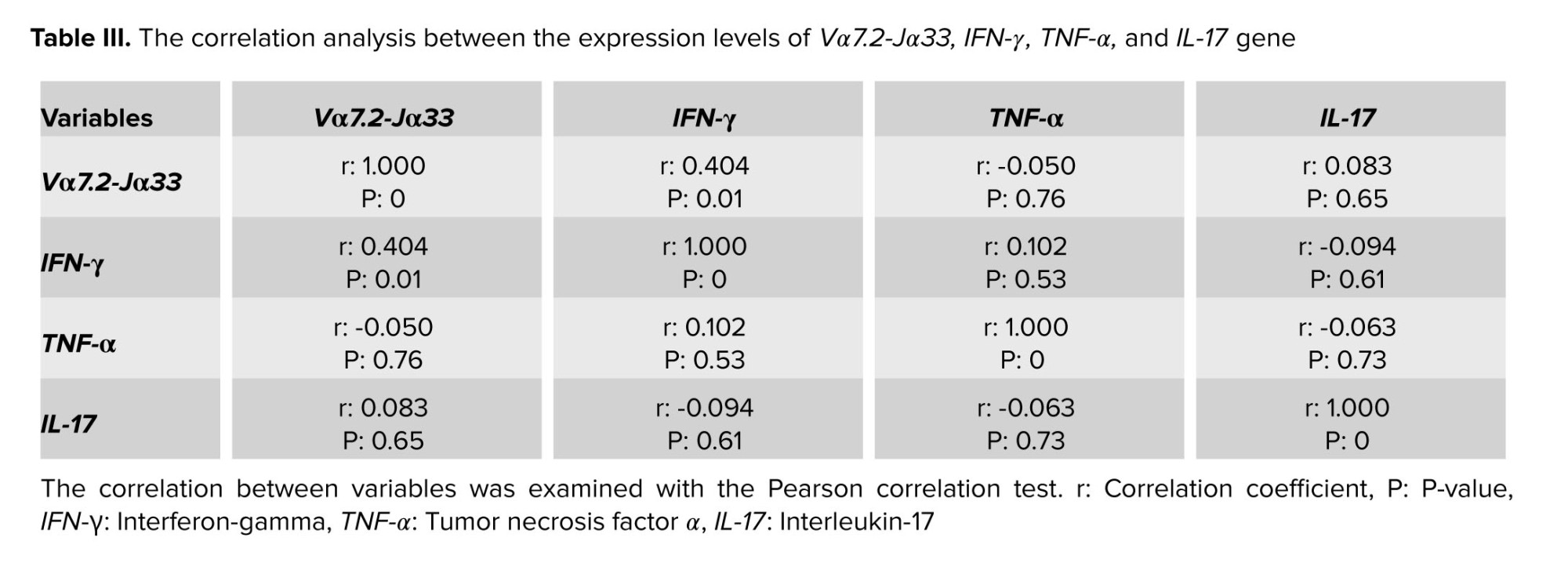

As indicated in table III, Vα7.2-Jα33 mRNA was expressed in all samples, and no significant difference was observed in expression between ectopic and eutopic tissue, with p = 0.54. Furthermore, the expression of this gene in ectopic tissue was higher than in the control group but it is not significant with p = 0.16 (Table II, Figure 6).

3.3.5. The results of investigating the correlation between the expression levels of Vα7.2-Jα33 and IFN-γ, and TNF-α and IL-17

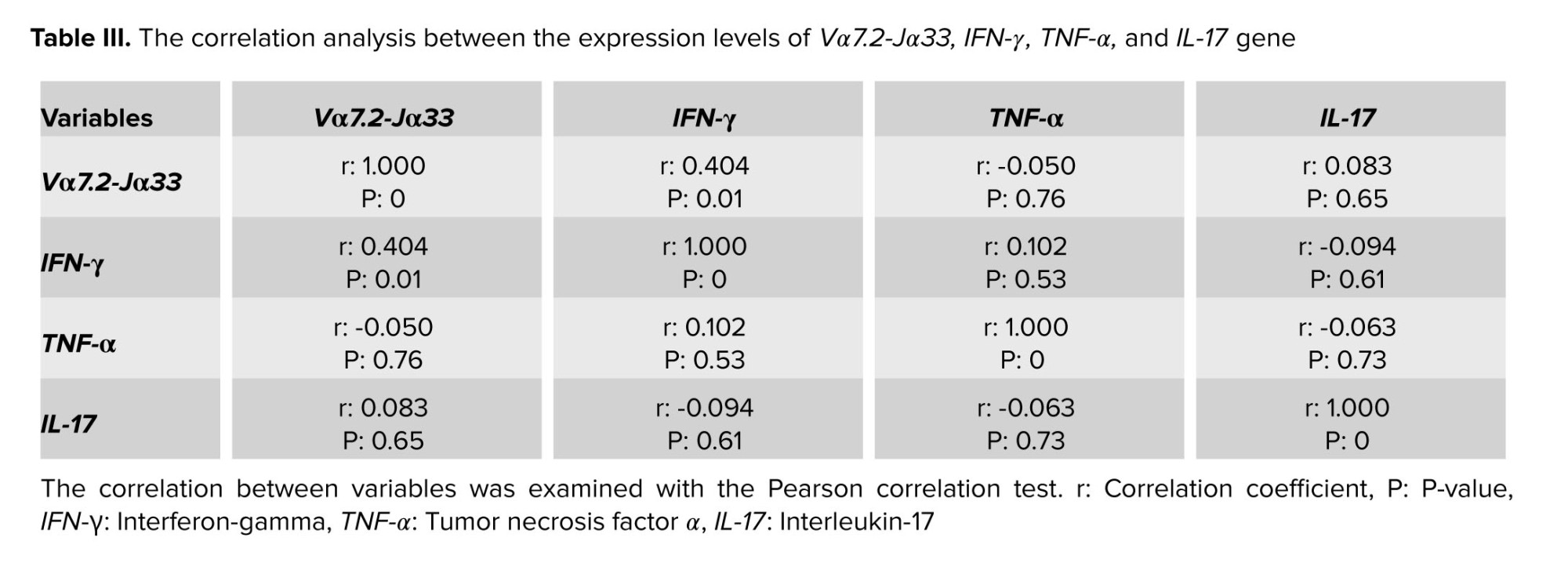

The correlation test results show a positive relationship between Vα7.2 Jα33 and IFN-γ expression levels in endometriotic tissue from endometriosis participants (p: 0.01, r: 0.404).

4. Discussion

Despite numerous efforts to determine the etiology of endometriosis, the exact role of immune system components, especially MAIT cells, remains unknown. Based on previous findings in ovarian endometriotic a large number of immune cells were found in the lesions, but the majority of these cells had an immunosuppressive phenotype, implying defects in immune surveillance functions caused by a suboptimal immune response, which led to the development of endometriosis (13).

Recently, based on our increased understanding of MAIT cell potential in inflammatory responses and ample proof of the cells' existence in female vaginal mucosal organs, the cells have become suspects in infertility and reproduction diseases. Not only do these cells have direct impacts on bacterial infection immunology, but they also play an important role in the progression of various mucosal-related cancers, such as colorectal cancer. Our findings reveal that MAIT cell infiltration into grade III and IV endometriotic lesions is minimal, but we approve of the cell's presence in ectopic and utopic ovarian endometriosis environments. Also, with the increase in the sample size, there is a possibility that the difference between the ectopic group and the control group will reach a significant level. A low-level of Vα7.2-Jα33 MAIT cells are present in uterine tissues, while the influx of CD8-positive MAIT cells in peritoneal fluid of endometriosis participants was significantly elevated (14).

Related previous research found that lymphocytes in endometriosis tissue have a higher capacity for IFN-γ production than cells in eutopic tissues (15). MAIT cells in the uterus have an active phenotype and a high potential for IFN-γ production. Our findings revealed a substantial increase in the expression of IFN-γ mRNA in ectopic tissue as compared to eutopic and control groups. More importantly, correlation analysis indicated that IFN-γ expression levels have a positive connection with Vα7.2-Jα33 gene expression, implying that MAIT cells may be a source of the cytokine in ectopic lesions. An in vitro study discovered that combining IFN-γ and IL-10 can increase ectopic cell proliferation and penetration (16).

As a result, MAIT cells play a role in the development of endometriosis by generating IFN-γ. According to these data, although the frequency of MAIT cells in the endometrium is low, their potential to produce cytokines can induce inflammatory responses. Also IFN-γ generating MAIT cell play role in pathogenesis of lung cancer and type 1 diabetes through increasing inflammation (17, 18).

Other studies defined increase and pathogenic role of this cytokine in peritoneal fluid and eutopic endometrium of participant with endometriosis through increase inflammation and up-regulate the expression of sICAM-1 in eutopic endometrium and interfere with immune function by ICAM-1, respectively (19, 20).

Our findings further confirmed that IL-17A gene expression increased in eutopic and ectopic endometriosis tissue as compared to control groups. T helper-17 and ectopic lesion in endometriotic tissue producing IL-17 can lead to progression of endometriosis through increasing inflammation (4). Our statistical analysis did not reveal a correlation between elevated IL-17A and Vα7.2-Jα33, indicating that the cytokine's source is not MAIT cells in the tissues. The potential of MAIT cells to produce IL-17 has already been proven in numerous autoimmune illnesses and immunological disorders. Despite IL-17 conventional role in inflammation, newly discovered angiogenic characteristics of the cytokine may increase endometriotic cell growth (21). MAIT, Th17, and IL-17, when combined, can cause a pro-inflammatory response. However, the immunosuppressive action of MAIT cells has been found in some instances (14, 22). Interestingly, MAIT cells, due to their potential to develop myeloid-derived suppressor cells and neutrophils, may promote tumor growth and carcinogenesis (23).

Even though TNF-α was found to be highly expressed in eutopic tissue, correlation analysis revealed no significant relationship with Vα7.2-Jα33 gene expression. In other studies, TNF-α expression was found to be significantly higher in ectopic endometriosis tissue than in eutopic tissue (24). Inconsistently, in another study, TNF-α gene expression did not show significant differences in ectopic ovarian tissue and endometrial uterine tissues (25).

High expression of t-bet (specific transcription factor of T helper-1) in eutopic tissue show high existence of T helper-1 in eutopic tissue which can produce TNF in this place (26). According to new research, TNF-α also decreases the expression of miR-183 in eutopic and ectopic tissue, leading to increased endometriotic cell invasion and proliferation (27). TNF-α also promotes angiogenesis by raising the expression of prokineticin-1 in eutopic tissue (28). In inflammatory situations, progesterone receptors are downregulated under effect of TNF-α, and progesterone resistance develops, leading to endometriosis (29). Furthermore, TNF-α by inducing PGE2 in stromal cells of eutopic tissue, promotes the progression of endometriosis (30).

However, to achieve a more detailed understanding of the role of MAIT cells in this disease; examining the subgroups of this cell )CD4+, CD8+, and CD4/CD8−/− [double negative, DN](, determining their frequency and activity with CD marker in both the initial and final stages of the disease, and also increasing the number of participants for further studies were put on the agenda.

5. Conclusion

MAIT cells, which are innate immune cells, are found in low numbers in the ectopic ovarian tissue of endometriosis participants and may play a role in disease pathogenesis by secreting IFN-γ.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Ali Shams and Abbas Khalili designed the study and conducted the research. Fateme Zare and Maryam Zare Moghadam and Reyhane Sandoghsaz evaluated essential criteria for selecting patients and carried out the experiments and analyzed the result of the study. All authors approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

Authors appreciate participants who accepted to take part in the study. We would also like to show our gratitude to the Dr. Javaheri her assistance in selecting the patients and taking the samples and other staff in gynecology ward of Shahid Sadoughi hospital, Yazd, Iran. Financial support was provided from Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (grant number: 10604).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Full-Text: (142 Views)

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by endometrium-like tissue proliferation and development outside the uterus. The main symptoms of the condition are pain, infertility, adenomyosis, inflammation, and alterations in the placentation (1). "Endometriosis affects 10-15% of all women of reproductive age and 70% of women with chronic pelvic pain" (2). Despite several investigations, many concerns about endometriosis pathogenesis remain unanswered. Endometriosis is caused by a combination of variables, including genetics, immunological and hormonal characteristics, and prostaglandin metabolism (3).

Previous research has found alterations in the frequency and function of immune cells in endometriosis participants' peripheral blood, peritoneal fluid, and endometriotic tissue, which supports the involvement of immune responses in this disease (4). Although endometriosis is an inflammatory disease, immune-suppressing cells like M2 macrophages (type 2 macrophage), regulatory T cells, helper T cells type 2, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as well as related cytokines like interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming growth factor beta, have all been linked to disease progression (5-7). Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells are a type of T cell with a non-variable alpha chain receptor known as Vα7.2-Jα33 and a limited diversity beta chain restricted to a non-polymorphic major histocompatibility complex I known as MR-1 in humans. These cells have a variety of surface markers, including CD3, CD25, CD8αα, CCR25, CCR6, CCR9, and CXCR6, CD122, CD95, CD69, CD27, and CD161, and their number varies according to the tissue. Their prevalence in the liver and the intestinal lamina propria is 20-50% and 1-10%, respectively. MAIT cells in humans are activated by the specific identification of bacterial and fungal antigens (including vitamin B2 and B9 metabolites) on MR-1 molecules. MAIT cells also express IL-18 and IL-12R permanently, resulting in cell activation by IL-12 or IL-18 (8). According to recent findings, MAIT cells have a role in mucosal immune response and the maintenance of lung and gut mucosal tissues. Bister and colleagues demonstrated that MAIT cells persist in the endometrium and decidua, resulting in powerful defense responses against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Furthermore, the existence of MAIT cells in vaginal mucous and their function are allegedly dependent on Th17 and the IL-17/IL-22 axis. MAIT cell frequency rises in infected and inflamed tissues, either by blood movement or local proliferation at infected locations (9-12).

Most findings have supported enhanced inflammation in ectopic lesions, although there is very little information on MAIT cells in the development of inflammation in endometriosis lesions, as well as the cells' potential to produce IL-17, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in the tissues. Given the importance of MAIT cells in mucosa-dependent immunity and lack of understanding of their role in endometriosis, this study intends to evaluate the cells role in the illness. This study aims to gain more knowledge in the field of MAIT cells in mucosal immune defense, the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases as well as cancer, as well as the lack of sufficient information about the role of this innate immune cell in endometriosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant population

Sample collection for this case-control study was performed in Obstetrics and Gynecology Departments of Shahid Sadoughi hospitals and sample analysis was conducted in Reproductive Immunology Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran from May 2021 to September 2022. 20 endometriosis women with stage III, IV were discernment through laparoscopy and 20 eutopic and ectopic tissue was prepared. As a control group, 20 healthy women who underwent laparoscopy for diagnostic reasons, tubal disconnection, ovarian cystectomy, ovarian drilling were included in the study. Women who had previously received hormonal medications, immunosuppressive drugs, or had a history of autoimmune, cancer, or infectious disorders were excluded from participating in the research. Before the start of the study, all participants were asked to fill out an informed consent form.

2.2. Gene expression in endometriotic tissue

2.2.1. Samples collection

The specimen tissues that were resected by laparoscopy method were 50-100 mg, they were later frozen in the RNA solution and were kept at -80°C until extraction of mRNA to preserve their RNA stability.

2.2.2. mRNA extractions

Homogenization was carried out using a sterile syringe and needle. Cell and tissue lysates were passed through a 20-gauge (0.9 mm) needle at least 5-10 times. TRIPURE Isolation Reagent kit )Gene-Foci, Switzerland( was used for RNA extraction and this process was carried out according to the kit instructions. Concentration, purity, and quality of extracted RNA were defined using spectrophotometric analysis (Thermo Fisher NanoDrop). All the disposal equipment used during the RNA extraction process was RNAase free.

2.2.3. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method

cDNA was synthesized of template mRNA according to the kit's instructions. The PCR reactions were carried out in a 20 µl total mixture volume including: 500 ng RNA, 10 µL buffer-mix (2x), 2 µl enzyme, and 8 µl of DEPC-treated. PCRs cycles were started by incubating the mixture for 4 min at 95oC, followed by 35 cycles composed of 94oC for 30 sec, 57oC for 30 sec, 72oC for 30 sec, and 72oC for 5 min and product size was confirmed on 1% agarose gel.

2.2.4. Quantitative real-time PCR method

The SYBER green PCR master mix was used in accordance with the kit protocol, and the mRNA expression levels were evaluated using the ABI/PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). Thermal cycling settings included 5 min at 95oC, followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95oC, 60 sec at 61oC, and 45 sec at 72oC. Beacon designer 7.9 software was used to design specific primers for amplification of desired genes in the form of exon junction (in this method, one of the primers is designed exactly on the junction of exons) and intron inclusion (in this method, an intron with a length of at least 300 bp was performed). Table I provided the primer Vα7.2-Jα33 (13).

2.3. Ethical considerations

Each participant provided written informed consent before participating in the study. This research was supported by a grant from Research Ethics Committees of Shahid Sadoughi University of Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1400.097).2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical package for social science version 25 was used for statistical analysis. For normality distribution Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were performed, where they found that the data were not normally distributed by p < 0.05. So, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for the comparison of IFN-γ, IL-17-A, TNF-α, and Vα7.2-Jα33 levels in each group against the control group. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the analytes in all groups. Also, we repeated measures of tests for the evaluation of the analytes at different times. The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Any p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graphpad Software Company, USA).3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the studied subjects

In this study, the average age and weight of women in the control group were 41 yr and 71 kg, respectively, while of those in the patient group were 35 yr and 64 kg, respectively.

3.2. Quality control results of synthesized cDNA

The electrophoresis technique was used to assess the quality of the cDNA produced. Following cDNA synthesis, cDNA-containing samples were run on an agarose gel, yielding bands Vα7.2-Jα33 with a length of 104 bp, IFN-γ with a length of 220 bp, TNF-α with a length of 143 bp, IL-17A with a length of 102 bp (Figure 1), and melt curve of IFN-γ was observed in figure 2.

3.3. Real-time PCR results

3.3.1. Comparison of IFN-γ gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

Table II shows that the expression of IFN-γ in ectopic tissue was significantly higher than in eutopic endometrium and normal endometrium, with p = 0.008 and p = 0.01 respectively. Furthermore, the expression of this gene in eutopic tissue does not differ significantly from the control group (Table II, Figure 3).

3.3.2. Comparison of TNF-α gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

As shown in figure 3, the expression of TNF-α in eutopic tissue was significantly higher than in ectopic tissue with p = 0.01 (Table II, Figure 4).

3.3.3. Comparison of IL-17A gene expression in endometriosis participants with control group

Our results demonstrated that IL-17A expression in ectopic tissue was considerably higher than in eutopic and control groups, with p = 0.002 (Table II, Figure 5).

3.3.4. The results of examining the expression of Vα7.2 Jα33 gene in ectopic, eutopic, and control tissue

As indicated in table III, Vα7.2-Jα33 mRNA was expressed in all samples, and no significant difference was observed in expression between ectopic and eutopic tissue, with p = 0.54. Furthermore, the expression of this gene in ectopic tissue was higher than in the control group but it is not significant with p = 0.16 (Table II, Figure 6).

3.3.5. The results of investigating the correlation between the expression levels of Vα7.2-Jα33 and IFN-γ, and TNF-α and IL-17

The correlation test results show a positive relationship between Vα7.2 Jα33 and IFN-γ expression levels in endometriotic tissue from endometriosis participants (p: 0.01, r: 0.404).

4. Discussion

Despite numerous efforts to determine the etiology of endometriosis, the exact role of immune system components, especially MAIT cells, remains unknown. Based on previous findings in ovarian endometriotic a large number of immune cells were found in the lesions, but the majority of these cells had an immunosuppressive phenotype, implying defects in immune surveillance functions caused by a suboptimal immune response, which led to the development of endometriosis (13).

Recently, based on our increased understanding of MAIT cell potential in inflammatory responses and ample proof of the cells' existence in female vaginal mucosal organs, the cells have become suspects in infertility and reproduction diseases. Not only do these cells have direct impacts on bacterial infection immunology, but they also play an important role in the progression of various mucosal-related cancers, such as colorectal cancer. Our findings reveal that MAIT cell infiltration into grade III and IV endometriotic lesions is minimal, but we approve of the cell's presence in ectopic and utopic ovarian endometriosis environments. Also, with the increase in the sample size, there is a possibility that the difference between the ectopic group and the control group will reach a significant level. A low-level of Vα7.2-Jα33 MAIT cells are present in uterine tissues, while the influx of CD8-positive MAIT cells in peritoneal fluid of endometriosis participants was significantly elevated (14).

Related previous research found that lymphocytes in endometriosis tissue have a higher capacity for IFN-γ production than cells in eutopic tissues (15). MAIT cells in the uterus have an active phenotype and a high potential for IFN-γ production. Our findings revealed a substantial increase in the expression of IFN-γ mRNA in ectopic tissue as compared to eutopic and control groups. More importantly, correlation analysis indicated that IFN-γ expression levels have a positive connection with Vα7.2-Jα33 gene expression, implying that MAIT cells may be a source of the cytokine in ectopic lesions. An in vitro study discovered that combining IFN-γ and IL-10 can increase ectopic cell proliferation and penetration (16).

As a result, MAIT cells play a role in the development of endometriosis by generating IFN-γ. According to these data, although the frequency of MAIT cells in the endometrium is low, their potential to produce cytokines can induce inflammatory responses. Also IFN-γ generating MAIT cell play role in pathogenesis of lung cancer and type 1 diabetes through increasing inflammation (17, 18).

Other studies defined increase and pathogenic role of this cytokine in peritoneal fluid and eutopic endometrium of participant with endometriosis through increase inflammation and up-regulate the expression of sICAM-1 in eutopic endometrium and interfere with immune function by ICAM-1, respectively (19, 20).

Our findings further confirmed that IL-17A gene expression increased in eutopic and ectopic endometriosis tissue as compared to control groups. T helper-17 and ectopic lesion in endometriotic tissue producing IL-17 can lead to progression of endometriosis through increasing inflammation (4). Our statistical analysis did not reveal a correlation between elevated IL-17A and Vα7.2-Jα33, indicating that the cytokine's source is not MAIT cells in the tissues. The potential of MAIT cells to produce IL-17 has already been proven in numerous autoimmune illnesses and immunological disorders. Despite IL-17 conventional role in inflammation, newly discovered angiogenic characteristics of the cytokine may increase endometriotic cell growth (21). MAIT, Th17, and IL-17, when combined, can cause a pro-inflammatory response. However, the immunosuppressive action of MAIT cells has been found in some instances (14, 22). Interestingly, MAIT cells, due to their potential to develop myeloid-derived suppressor cells and neutrophils, may promote tumor growth and carcinogenesis (23).

Even though TNF-α was found to be highly expressed in eutopic tissue, correlation analysis revealed no significant relationship with Vα7.2-Jα33 gene expression. In other studies, TNF-α expression was found to be significantly higher in ectopic endometriosis tissue than in eutopic tissue (24). Inconsistently, in another study, TNF-α gene expression did not show significant differences in ectopic ovarian tissue and endometrial uterine tissues (25).

High expression of t-bet (specific transcription factor of T helper-1) in eutopic tissue show high existence of T helper-1 in eutopic tissue which can produce TNF in this place (26). According to new research, TNF-α also decreases the expression of miR-183 in eutopic and ectopic tissue, leading to increased endometriotic cell invasion and proliferation (27). TNF-α also promotes angiogenesis by raising the expression of prokineticin-1 in eutopic tissue (28). In inflammatory situations, progesterone receptors are downregulated under effect of TNF-α, and progesterone resistance develops, leading to endometriosis (29). Furthermore, TNF-α by inducing PGE2 in stromal cells of eutopic tissue, promotes the progression of endometriosis (30).

However, to achieve a more detailed understanding of the role of MAIT cells in this disease; examining the subgroups of this cell )CD4+, CD8+, and CD4/CD8−/− [double negative, DN](, determining their frequency and activity with CD marker in both the initial and final stages of the disease, and also increasing the number of participants for further studies were put on the agenda.

5. Conclusion

MAIT cells, which are innate immune cells, are found in low numbers in the ectopic ovarian tissue of endometriosis participants and may play a role in disease pathogenesis by secreting IFN-γ.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Ali Shams and Abbas Khalili designed the study and conducted the research. Fateme Zare and Maryam Zare Moghadam and Reyhane Sandoghsaz evaluated essential criteria for selecting patients and carried out the experiments and analyzed the result of the study. All authors approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

Authors appreciate participants who accepted to take part in the study. We would also like to show our gratitude to the Dr. Javaheri her assistance in selecting the patients and taking the samples and other staff in gynecology ward of Shahid Sadoughi hospital, Yazd, Iran. Financial support was provided from Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (grant number: 10604).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Genetics

References

1. Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Gomel V, Martin DC. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: The genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril 2019; 111: 327-340. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.013] [PMID]

2. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 2017; 6: 34-41. [DOI:10.1007/s13669-017-0187-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Parazzini F, Esposito G, Tozzi L, Noli S, Bianchi S. Epidemiology of endometriosis and its comorbidities. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 209: 3-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.021] [PMID]

4. Zare Moghaddam M, Ansariniya H, Seifati SM, Zare F, Fesahat F. Immunopathogenesis of endometriosis: An overview of the role of innate and adaptive immune cells and their mediators. Am J Reprod Immunol 2022; 87: e13537. [DOI:10.1111/aji.13537] [PMID]

5. Classen J, Koschel J, Oehlwein C, Seppi K, Urban P, Winkler C, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations: Phenotypes, pathophysiology, management, and open issues. J Neural Transm 2017; 124: 1029-1036. [DOI:10.1007/s00702-017-1757-0] [PMID]

6. Xiao F, Liu X, Guo SW. Platelets and regulatory T cells may induce a type 2 immunity that is conducive to the progression and fibrogenesis of endometriosis. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 610963. [DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.610963] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Zhang T, Zhou J, Man GCW, Leung KT, Liang B, Xiao B, et al. MDSCs drive the process of endometriosis by enhancing angiogenesis and are a new potential therapeutic target. Eur J Immunol 2018; 48: 1059-1073. [DOI:10.1002/eji.201747417] [PMID] [PMCID]

8. Legoux F, Salou M, Lantz O. MAIT cell development and functions: The microbial connection. Immunity 2020; 53: 710-723. [DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.09.009] [PMID]

9. Nel I, Bertrand L, Toubal A, Lehuen A. MAIT cells, guardians of skin and mucosa? Mucosal Immunol 2021; 14: 803-814. [DOI:10.1038/s41385-021-00391-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

10. Meierovics A, Yankelevich W-JC, Cowley SC. MAIT cells are critical for optimal mucosal immune responses during in vivo pulmonary bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2013; 110: E3119-E3128. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1302799110] [PMID] [PMCID]

11. Bister J, Crona Guterstam Y, Strunz B, Dumitrescu B, Haij Bhattarai K, Özenci V, et al. Human endometrial MAIT cells are transiently tissue resident and respond to Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mucosal Immunol 2021; 14: 357-365. [DOI:10.1038/s41385-020-0331-5] [PMID]

12. Gibbs A, Leeansyah E, Introini A, Paquin-Proulx D, Hasselrot K, Andersson E, et al. MAIT cells reside in the female genital mucosa and are biased towards IL-17 and IL-22 production in response to bacterial stimulation. Mucosal Immunol 2017; 10: 35-45. [DOI:10.1038/mi.2016.30] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Xu H, Zhao J, Lu J, Sun X. Ovarian endometrioma infiltrating neutrophils orchestrate immunosuppressive microenvironment. J Ovarian Res 2020; 13: 44. [DOI:10.1186/s13048-020-00642-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

14. Li C, Lu Z, Bi K, Wang K, Xu Y, Guo P, et al. CD4+/CD8+ mucosa-associated invariant T cells foster the development of endometriosis: A pilot study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2019; 17: 78. [DOI:10.1186/s12958-019-0524-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

15. Chiang CM, Hill JA. Localization of T cells, interferon-gamma and HLA-DR in eutopic and ectopic human endometrium. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1997; 43: 245-250. [DOI:10.1159/000291866] [PMID]

16. Qiu X-M, Lai Z-Z, Ha S-Y, Yang H-L, Liu L-B, Wang Y, et al. IL-2 and IL-27 synergistically promote growth and invasion of endometriotic stromal cells by maintaining the balance of IFN-γ and IL-10 in endometriosis. Reproduction 2020; 159: 251-260. [DOI:10.1530/REP-19-0411] [PMID]

17. Zhang Q, Li P, Zhou W, Fang S, Wang J. Participation of increased circulating MAIT cells in lung cancer: A pilot study. J Cancer 2022; 13: 1623-1629. [DOI:10.7150/jca.69415] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Fan Q, Nan H, Li Z, Li B, Zhang F, Bi L. New insights into MAIT cells in autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2023; 159: 114250. [DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114250] [PMID]

19. Podgaec S, Dias Junior JA, Chapron C, Oliveira RM, Baracat EC, Abrão MS. Th1 and Th2 ummune responses related to pelvic endometriosis. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2010; 56: 92-98. [DOI:10.1590/S0104-42302010000100022] [PMID]

20. Yoo J-Y, Jeong J-W, Fazleabas AT, Tayade C, Young SL, Lessey BA. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 (PIAS3) is down-regulated in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Biol Reprod 2016; 95: 11. [DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.115.137158] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Ahn SH, Edwards AK, Singh SS, Young SL, Lessey BA, Tayade C. IL-17A contributes to the pathogenesis of endometriosis by triggering proinflammatory cytokines and angiogenic growth factors. J Immunol 2015; 195: 2591-2600. [DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1501138] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. Miller JE, Ahn SH, Marks RM, Monsanto SP, Fazleabas AT, Koti M, et al. IL-17A modulates peritoneal macrophage recruitment and M2 polarization in endometriosis. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 108. [DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00108] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Hana T, Terabe M. MAIT cells and MR1 play an immunosuppressive role in glioblastoma through the induction of neutrophils and MDSCs. bioRxiv. 2022:2022.07.17.499189. (Preprint)

24. He R, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang Z, Wang W, Fu L, et al. NLRC5 inhibits inflammation of secretory phase ectopic endometrial stromal cells by up-regulating autophagy in ovarian endometriosis. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11: 1281. [DOI:10.3389/fphar.2020.01281] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Odukoya OA, Ajjan R, Lim K, Watson P, Weetman AP, Cooke I. The pattern of cytokine mRNA expression in ovarian endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 1997; 3: 393-397. [DOI:10.1093/molehr/3.5.393] [PMID]

26. Koval HD, Chopyak VV, Kamyshnyi OM, Kurpisz MK. Transcription regulatory factor expression in T-helper cell differentiation pathway in eutopic endometrial tissue samples of women with endometriosis associated with infertility. Cent Eur J Immunol 2018; 43: 90-96. [DOI:10.5114/ceji.2018.74878] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Shi XY, Gu L, Chen J, Guo XR, Shi YL. Downregulation of miR-183 inhibits apoptosis and enhances the invasive potential of endometrial stromal cells in endometriosis. Int J Mol Med 2014; 33: 59-67. [DOI:10.3892/ijmm.2013.1536] [PMID] [PMCID]

28. Wu Y, Wu X. [Expression of PROK 1 and its receptor PROKR 1 in endometriosis and its clinical significance]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2019; 44: 621-627. (in Chinese)

29. Chae U, Min JY, Kim SH, Ihm HJ, Oh YS, Park SY, et al. Decreased progesterone receptor B/A ratio in endometrial cells by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis. Yonsei Med J 2016; 57: 1468-1474. [DOI:10.3349/ymj.2016.57.6.1468] [PMID] [PMCID]

30. Kim YA, Kim JY, Kim MR, Hwang KJ, Chang DY, Jeon MK. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis by stromal cell culture through nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J Reprod Med 2009; 54: 625-630.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |