Tue, Feb 24, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 6 (June 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(6): 493-506 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: No.20/6/2021/2022

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Almahmoud L, Altawil L, Shahatit Y, Sami R, Qatawneh A A, Alkhdaire Z M, et al . Knowledge and attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health among youth in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. IJRM 2025; 23 (6) :493-506

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3476-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3476-en.html

Lina Almahmoud *1

, Laith Altawil2

, Laith Altawil2

, Yazan Shahatit2

, Yazan Shahatit2

, Rawan Sami3

, Rawan Sami3

, Ayman Abdullah Qatawneh2

, Ayman Abdullah Qatawneh2

, Zaid Mohannad Alkhdaire2

, Zaid Mohannad Alkhdaire2

, Rajai Zurikat4

, Rajai Zurikat4

, Akram Mohammad Karmoul5

, Akram Mohammad Karmoul5

, Abdallah Abuawad3

, Abdallah Abuawad3

, Wasan Al-Dalabeeh3

, Wasan Al-Dalabeeh3

, Mohammad Abu Khait6

, Mohammad Abu Khait6

, Morad Bani-Hani7

, Morad Bani-Hani7

, Laith Altawil2

, Laith Altawil2

, Yazan Shahatit2

, Yazan Shahatit2

, Rawan Sami3

, Rawan Sami3

, Ayman Abdullah Qatawneh2

, Ayman Abdullah Qatawneh2

, Zaid Mohannad Alkhdaire2

, Zaid Mohannad Alkhdaire2

, Rajai Zurikat4

, Rajai Zurikat4

, Akram Mohammad Karmoul5

, Akram Mohammad Karmoul5

, Abdallah Abuawad3

, Abdallah Abuawad3

, Wasan Al-Dalabeeh3

, Wasan Al-Dalabeeh3

, Mohammad Abu Khait6

, Mohammad Abu Khait6

, Morad Bani-Hani7

, Morad Bani-Hani7

1- Department of Medical Doctors, Farah Medical Campus, Amman, Jordan. , linaalmahmoud@hotmail.com

2- Department of Medical Doctors, Farah Medical Campus, Amman, Jordan.

3- Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan.

4- Department of General Medicine, Hospitalist Services, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan.

5- Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University for Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan.

6- Faculty of Medicine, Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan.

7- Department of General Surgery, Urology, and Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan.

2- Department of Medical Doctors, Farah Medical Campus, Amman, Jordan.

3- Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan.

4- Department of General Medicine, Hospitalist Services, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan.

5- Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University for Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan.

6- Faculty of Medicine, Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan.

7- Department of General Surgery, Urology, and Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan.

Keywords: Sexual health, Health services, Health knowledge, Attitudes, Practice, Adolescent, Jordan.

Full-Text [PDF 410 kb]

(1152 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (739 Views)

Full-Text: (97 Views)

1. Introduction

Adolescents comprise approximately 16% of the global population(1) . Adolescence marks the critical transition period from childhood to adulthood, during which individuals undergo significant physiological and psychological changes, including puberty, which significantly shapes their choices, decisions, and overall health. This stage is characterized by hormonal changes, rapid physical growth, development of secondary sexual characteristics, and emotional shifts such as heightened sensitivity, mood swings, identity exploration, and increased desire for autonomy (2) . Developing an awareness of their sexuality is an essential aspect of this developmental stage (3) .

Pubertal health encompasses concepts that have contributed to the improvement of both physical and psychological health(4) . The World Health Organization's Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office asserts that schools have a significant role in maintaining and enhancing health and wellbeing. It implies that the community as a whole and families will gain from education for school students. However, understanding students' knowledge and attitudes toward pubertal health is essential for providing optimal education, as this enables the formulation of educational programs that are appropriately tailored to meet the needs of adolescents, addressing any gaps in their knowledge and attitudes (5) .

Youth who engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as early sexual initiation, unprotected intercourse, and multiple sexual partners, pose serious and risky consequences, including unwanted pregnancies, abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as HIV, and even death(6, 7) . Remarkably, people between the ages of 15 and 25 account for over 40% of new HIV cases worldwide. Adolescents are more likely to contribute to the transmission of STIs and are at higher risk of contracting them. This vulnerability is exacerbated by limited sexual health education, engagement in risky behaviors, regional and national conflicts, and inadequate access to reproductive health services (7) .

Recently, the age of puberty onset has declined, mainly due to improved nutrition and overall well-being. This earlier maturation is linked to an earlier initiation of sexual activity, which increases the risk of reproductive and sexual health issues, such as unprotected sex, early marriage, multiple sexual partnerships, and STIs like human papillomavirus and HIV(8) . Comprehensive education on sexual and reproductive health is essential during adolescence, in order to promote well-being and to prepare young individuals to navigate through the complexities of sexual maturation (9) . The provision of sexual and reproductive health services is widely acknowledged as a fundamental human right (10, 11) . Nevertheless, a significant number of adolescents in developing countries continue to face substantial barriers to access accurate information and necessary healthcare services in this domain (12) . Accessibility to these services in low to middle-income countries is affected by different socio-demographic factors such as age and educational level (13) .

Furthermore, due to social and cultural restrictions, stigma, and the misconception that discussing sexual health might lead to increased premarital sexual activity, parents, the media, and educational programs are failing to provide adequate information on sexual health(14, 15).

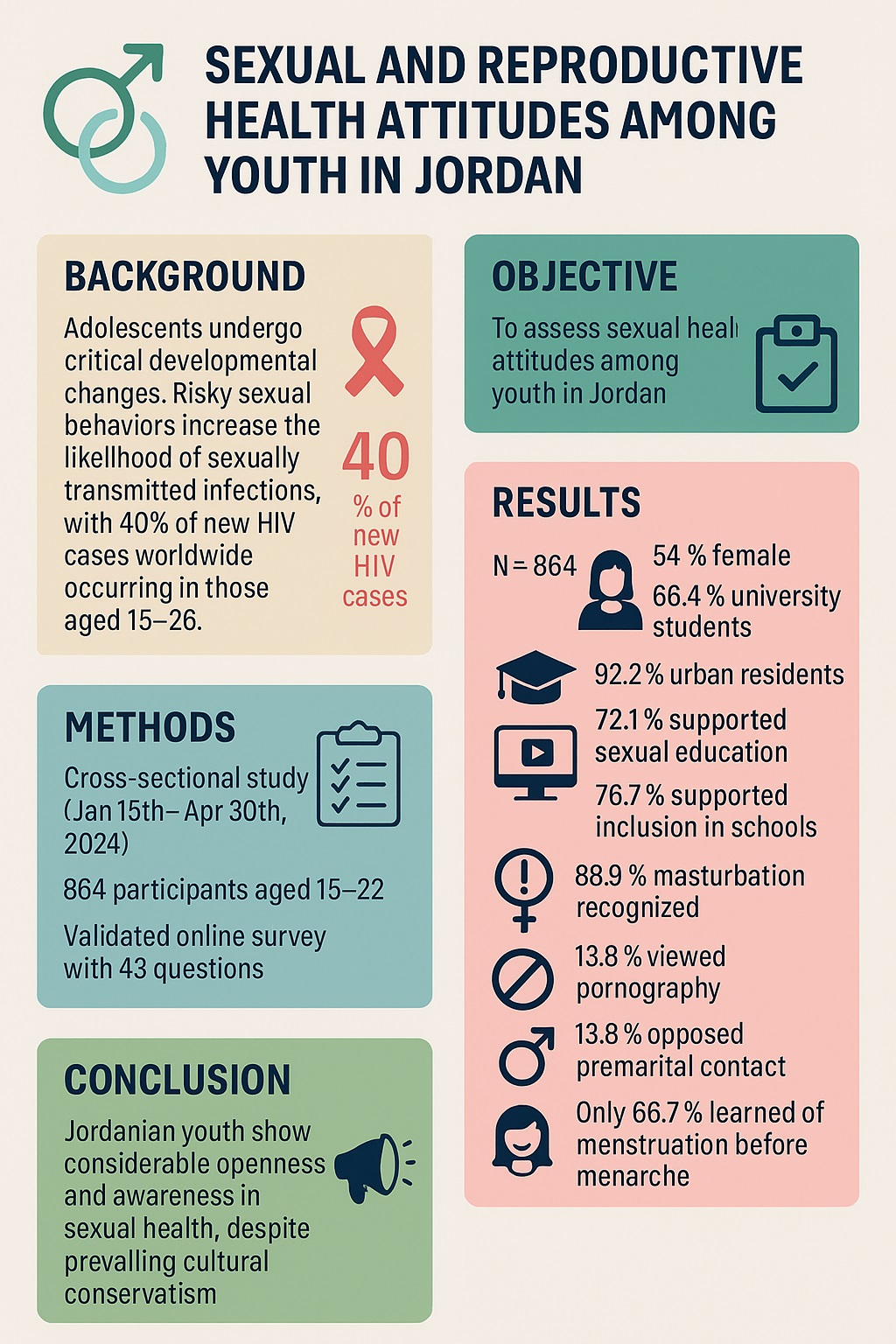

Given the importance of promoting sexual and reproductive health awareness among this age group, we conducted this study to assess Jordanian adolescents' attitudes and knowledge regarding sexual education and sexual and reproductive well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

During the process of preparing this study, we followed the STROBE guidelines(16) .

2.1. Sampling, population, and study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January to April, 2024. Our inclusion criteria were Jordanian youth aged 15-22 yr old who consented to participate. Respondents were assembled via opportunity (convenience) sampling. Individuals who did not fit our specified criteria were excluded from the study.

2.2. Study questionnaire and data collection

We utilized a validated, online, pilot-tested, and self-administered survey that was distributed through social media (Facebook and WhatsApp). Our research team adopted the survey after conducting thorough research in databases to find a similar survey used in a previous study conducted in Egypt(17) .

The questionnaire was piloted on 80 adolescents between 15 and 25 yr old representing different economic and cultural classes. We distributed the questionnaire to potential participants through social media platforms to ensure maximum participant reach.

The questionnaire was then uploaded to Google Forms after being translated from English to Arabic, and the Arabic questionnaire was validated.

The final questionnaire had 43 items total, split into 2 parts: 10 questions about the respondent's sociodemographic information were included in the first part, and 33 questions about knowledge and attitudes were included in the second part. The second part was divided into 4 sections: masturbation, sexual education, sexual intercourse and related presumptions, and pornography. There was a section at the end of the questionnaire, only for female respondents about menstruation knowledge and attitudes.

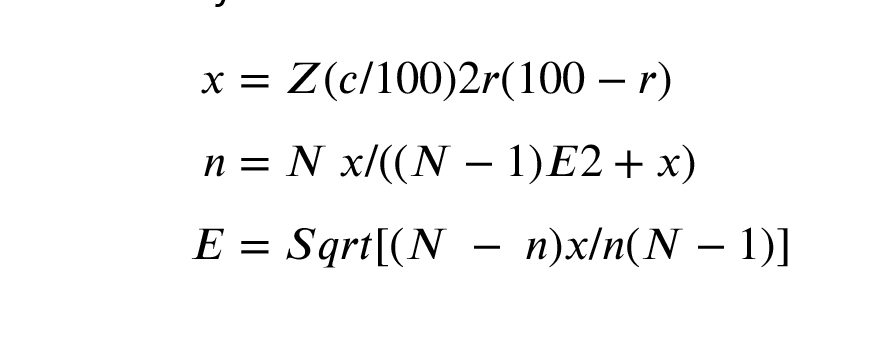

2.3. Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft® Software, with a margin error of 5%, confidence interval of 99%, response distribution of 50%, and a population of 10 million, yielding at least 664 respondents. As a result, 864 people were surveyed.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan (No.20/6/2021/2022). The first section of the questionnaire provided details about the study, including its purpose, the intended group of respondents, and information about the survey. Following this, respondents were asked to indicate their consent to participate in the survey. Their responses were completely confidential.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, we utilized IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 25, Chicago, IL, USA. Means and standard deviations were used to characterize numerical variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were used to characterize categorical variables.

3. Results

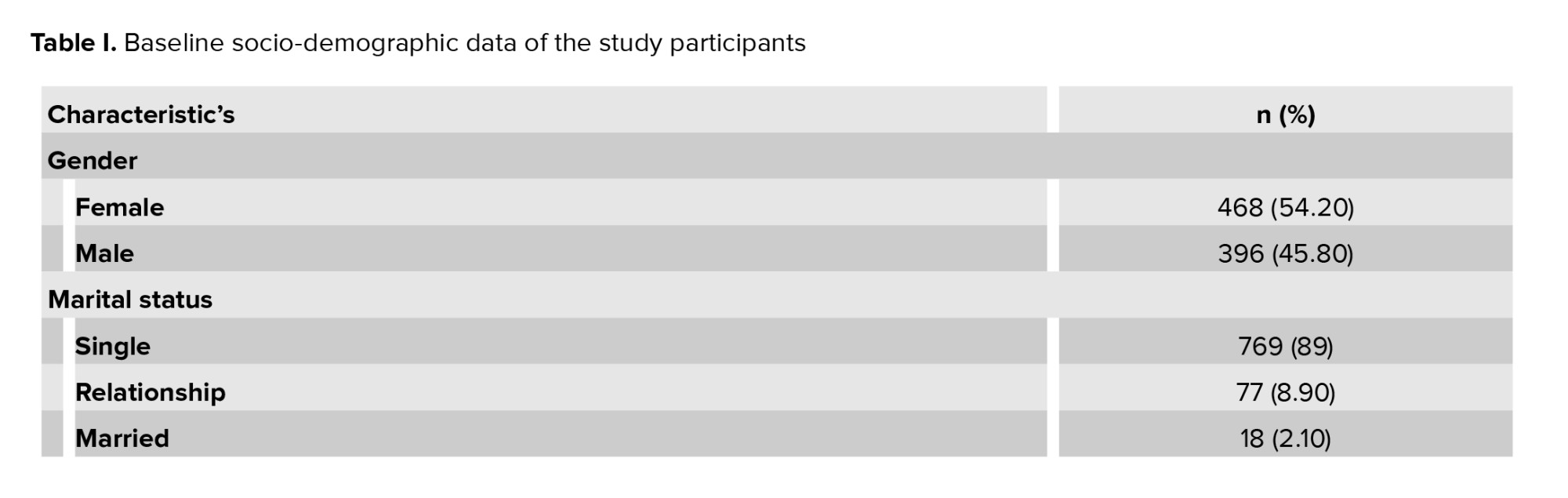

3.1. Socio-demographic data

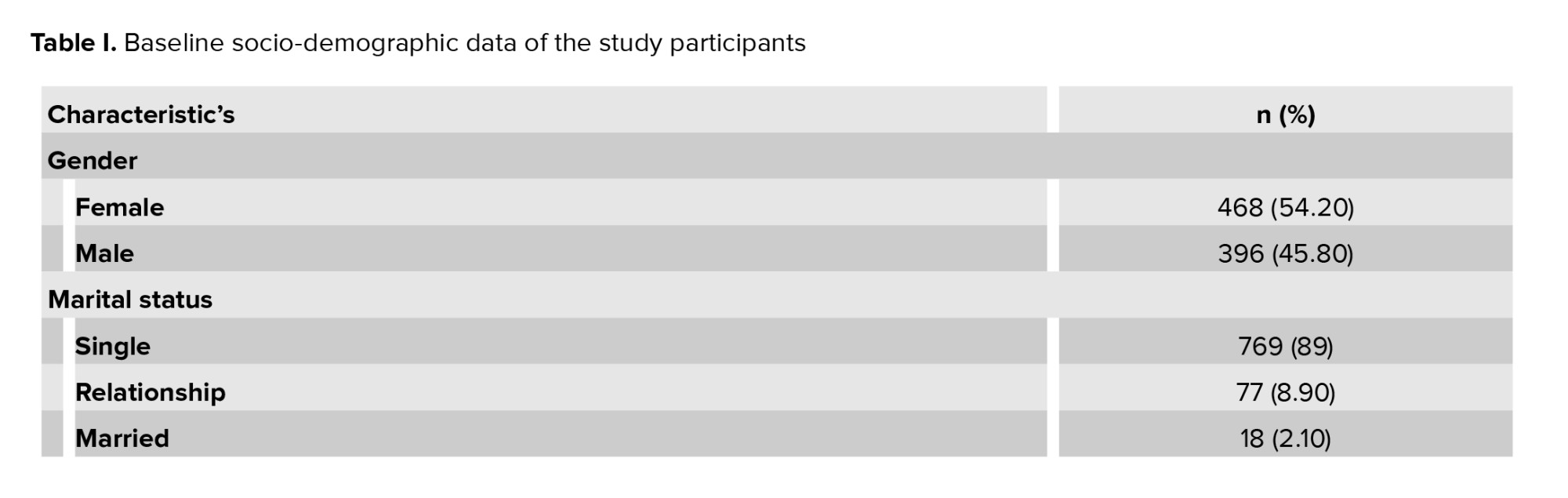

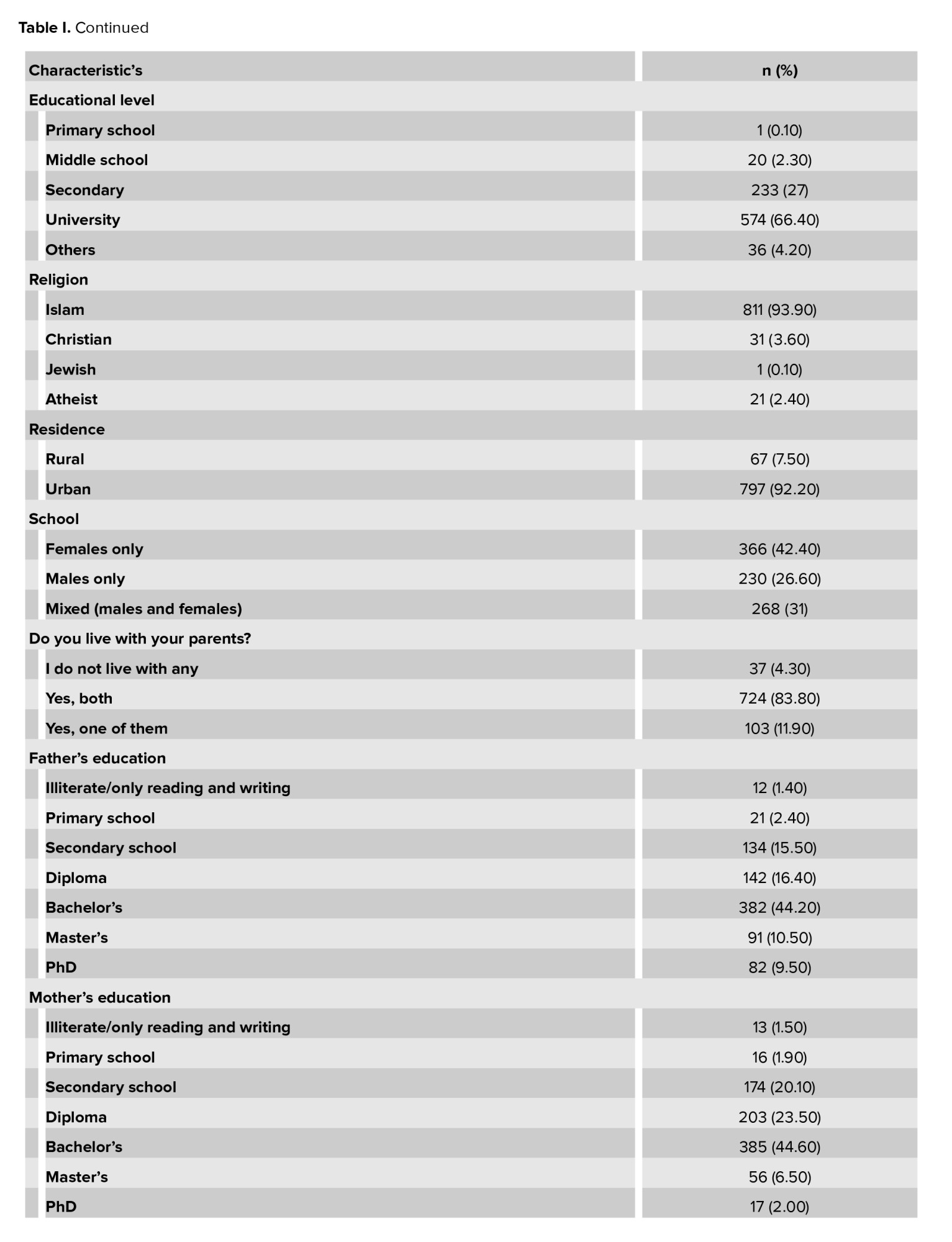

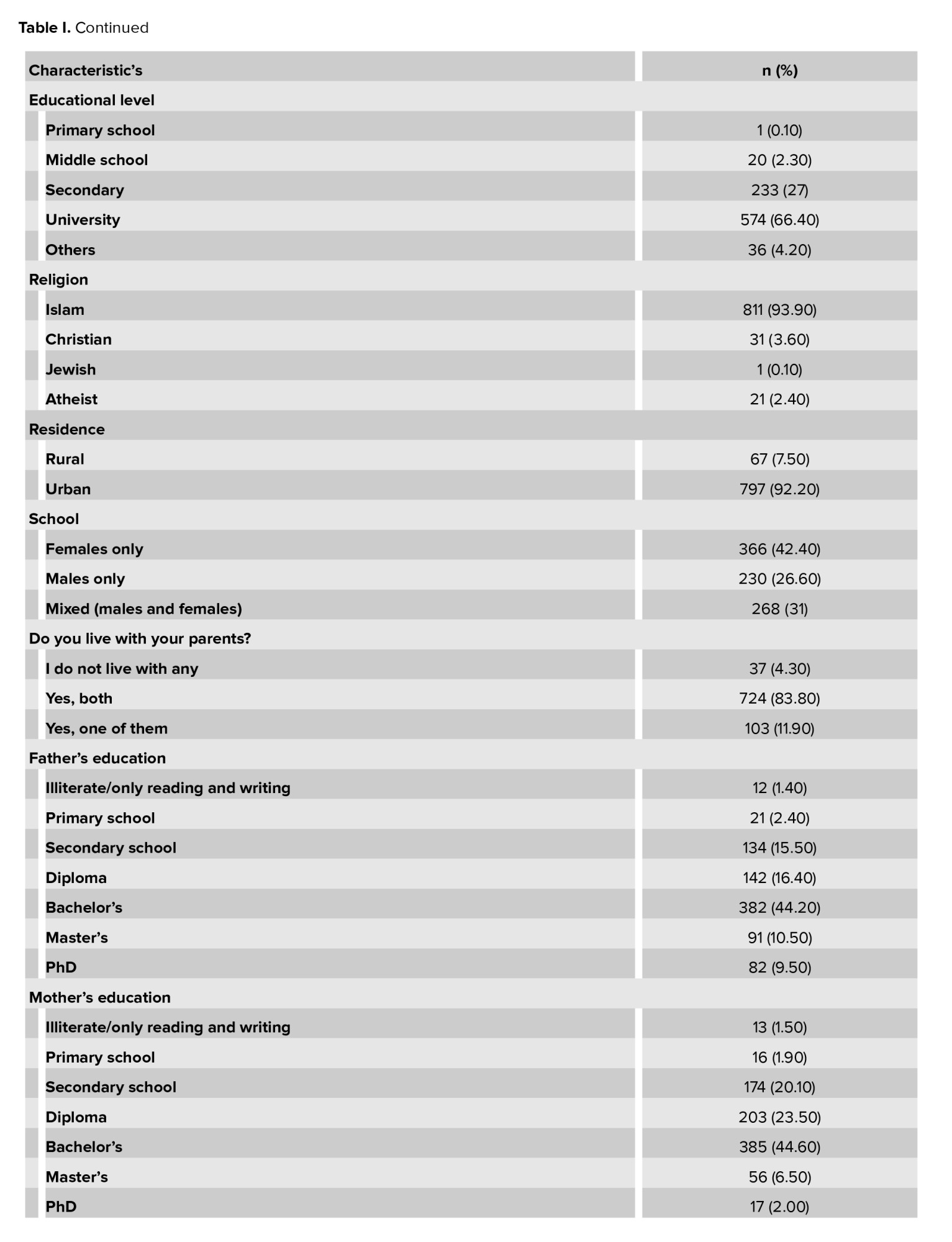

A total of 864 adolescents aged between 15 and 22 participated, of whom 54.2% (n = 468) were women and 45.8% (n = 396) were men. The majority of respondents were single, 769 (89%), and only 95 (11%) were in a relationship, of which 18 (2.1%) were married. University students comprised 574 of the respondents (66.4%), 233 (27%) completed secondary school, and only 20 (2.3%) are still in middle school. Most respondents reside in an urban area with their parents (Table I).

3.2. Sexual education and complementary attitudes

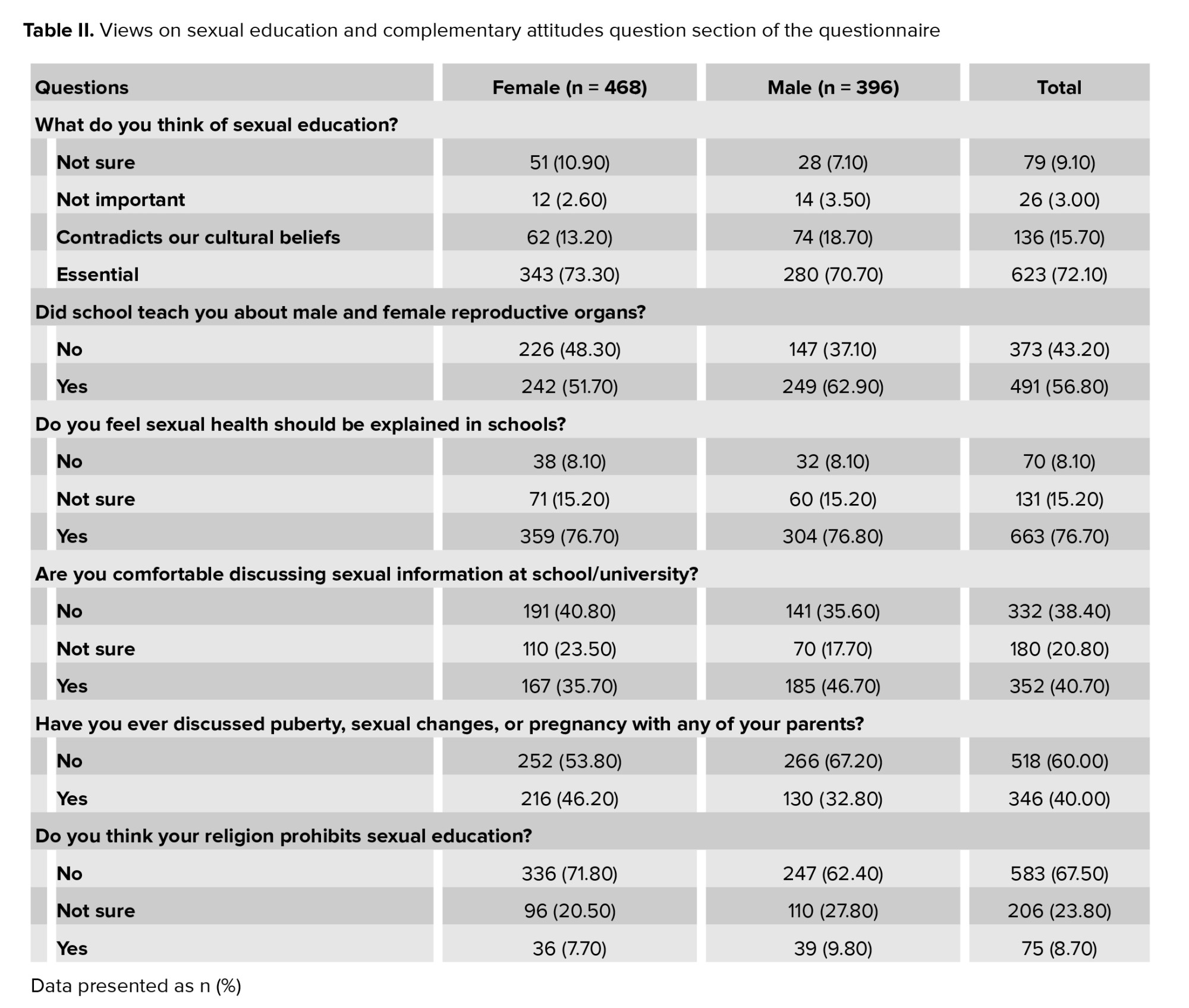

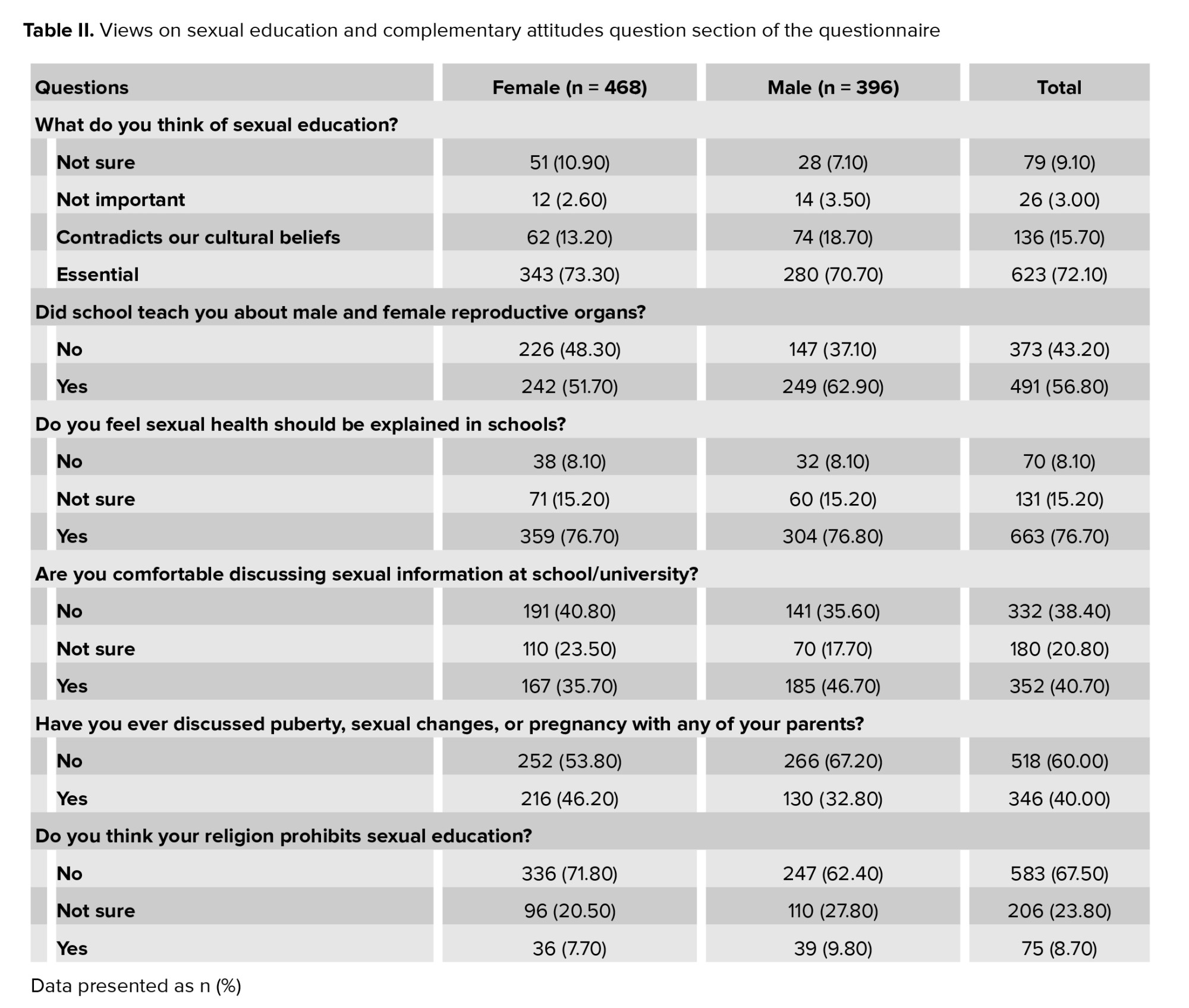

Sexual education is presumed necessary in 623 (72.1%), 136 (15.7%) respondents find that it contradicts cultural beliefs, 79 (9.1%) are not sure, and 26 (3%) think it is not important. 663 (76.7%) respondents advocate for sexual education in schools. However, only 491 (56.8%) have learned about male and female reproductive systems at school. Males were more likely than females to report confidence discussing sexual health in educational settings (46.7% vs. 35.7%). Additionally, 216 females and 130 males have ever discussed matters like puberty, sexual changes, or pregnancy with either parent. Most respondents, accounting for 583 (67.5%), believe that sexual and reproductive health education does not contradict religious beliefs. Table II shows more details on sexual education and complementary attitudes.

3.3. Masturbation and pornography

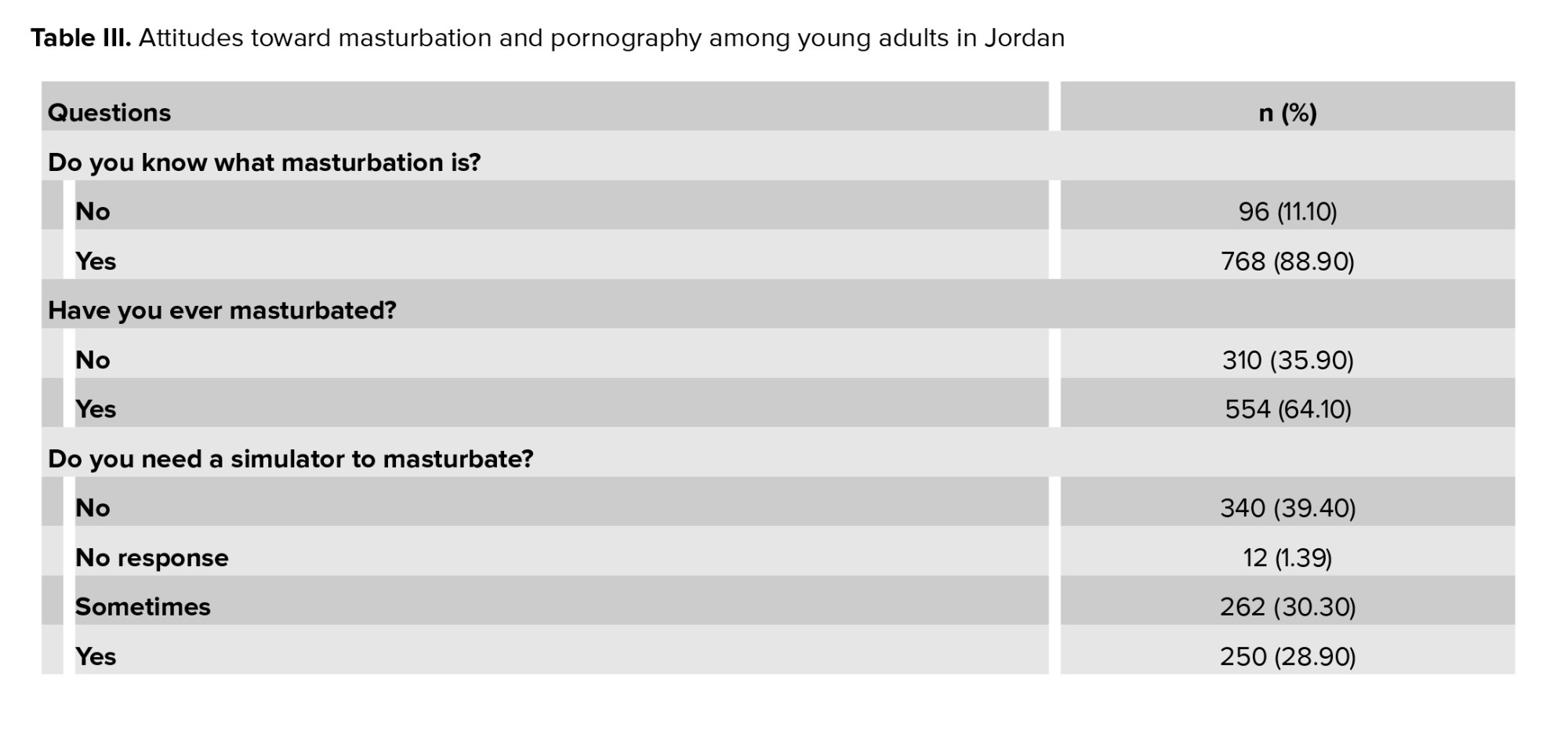

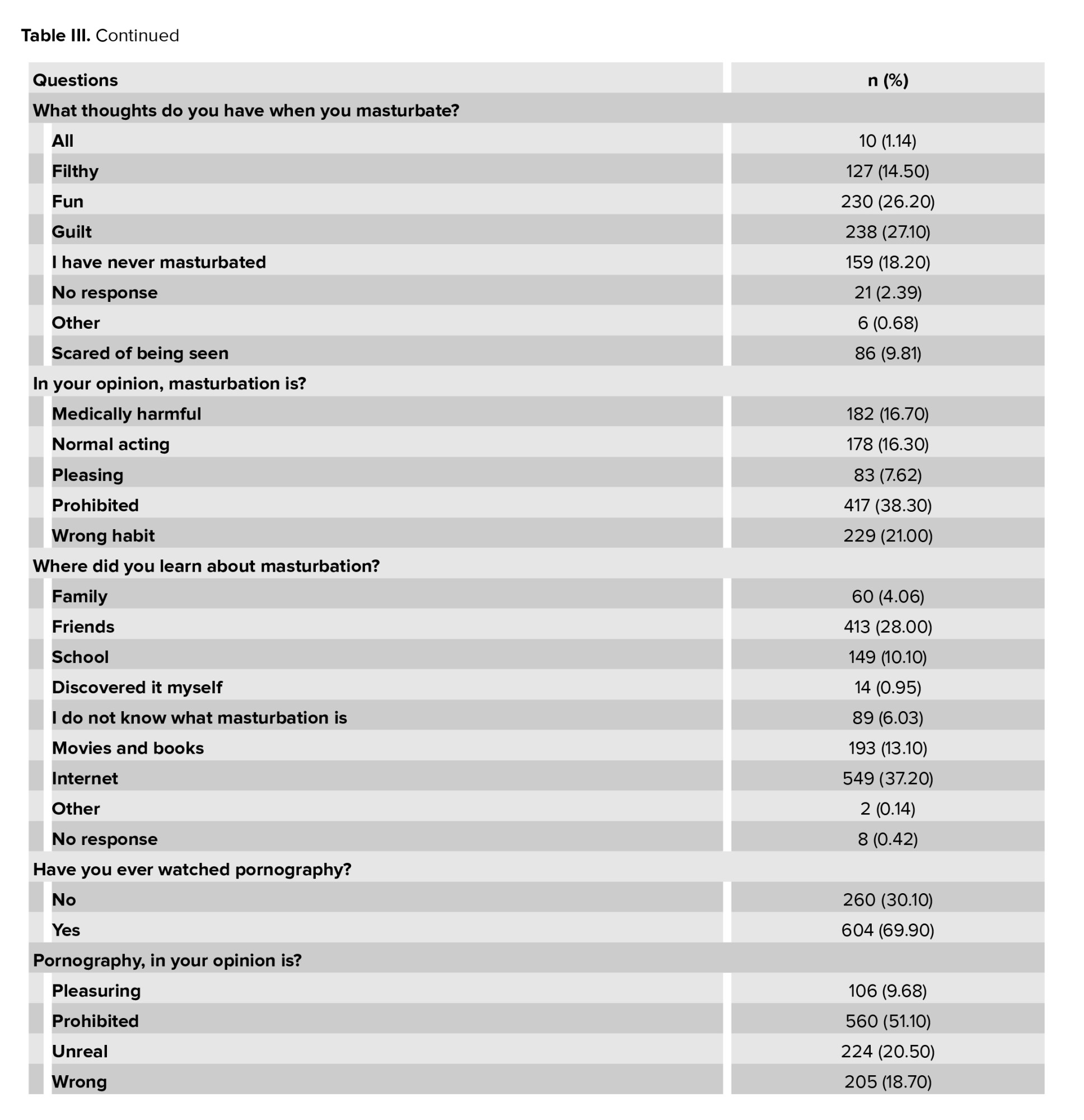

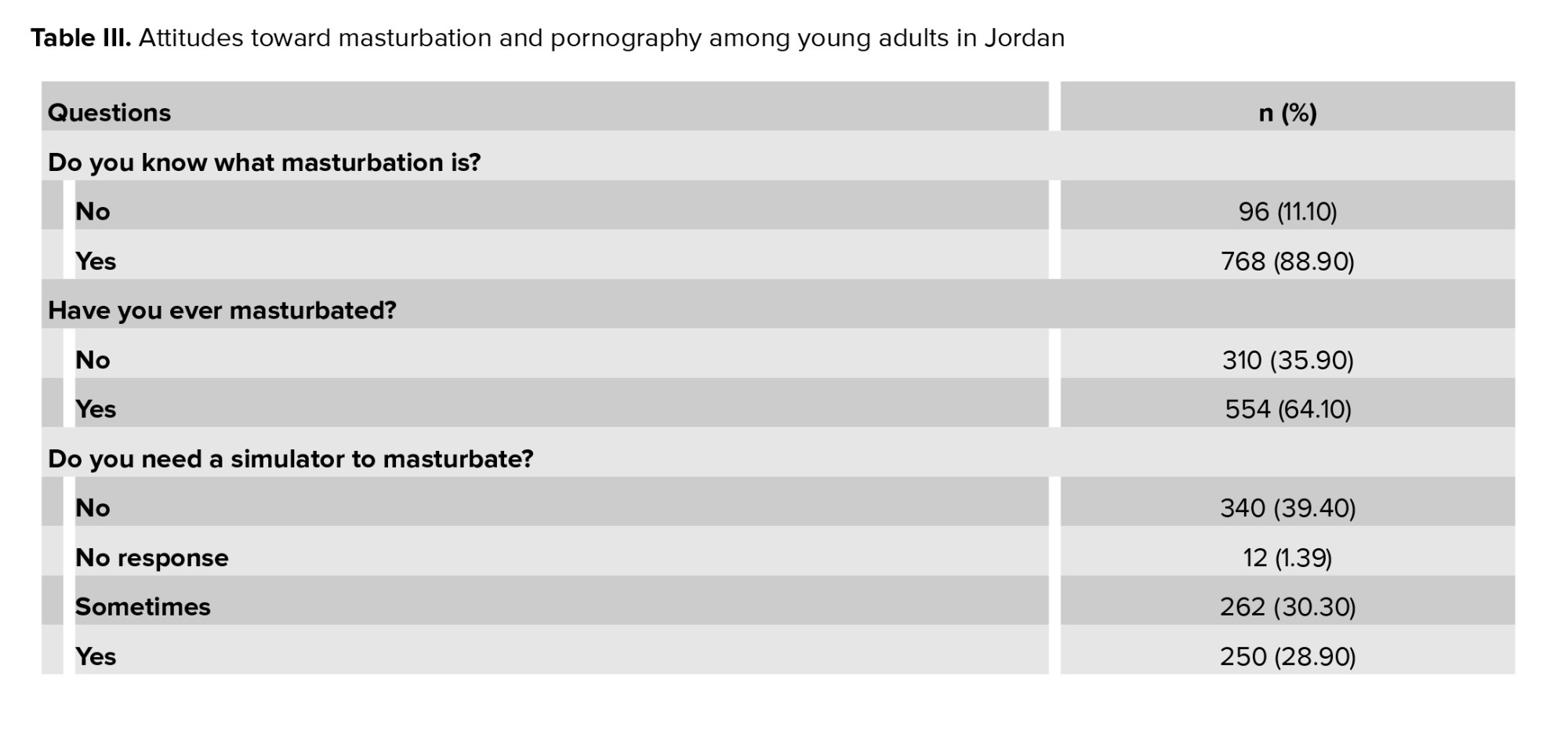

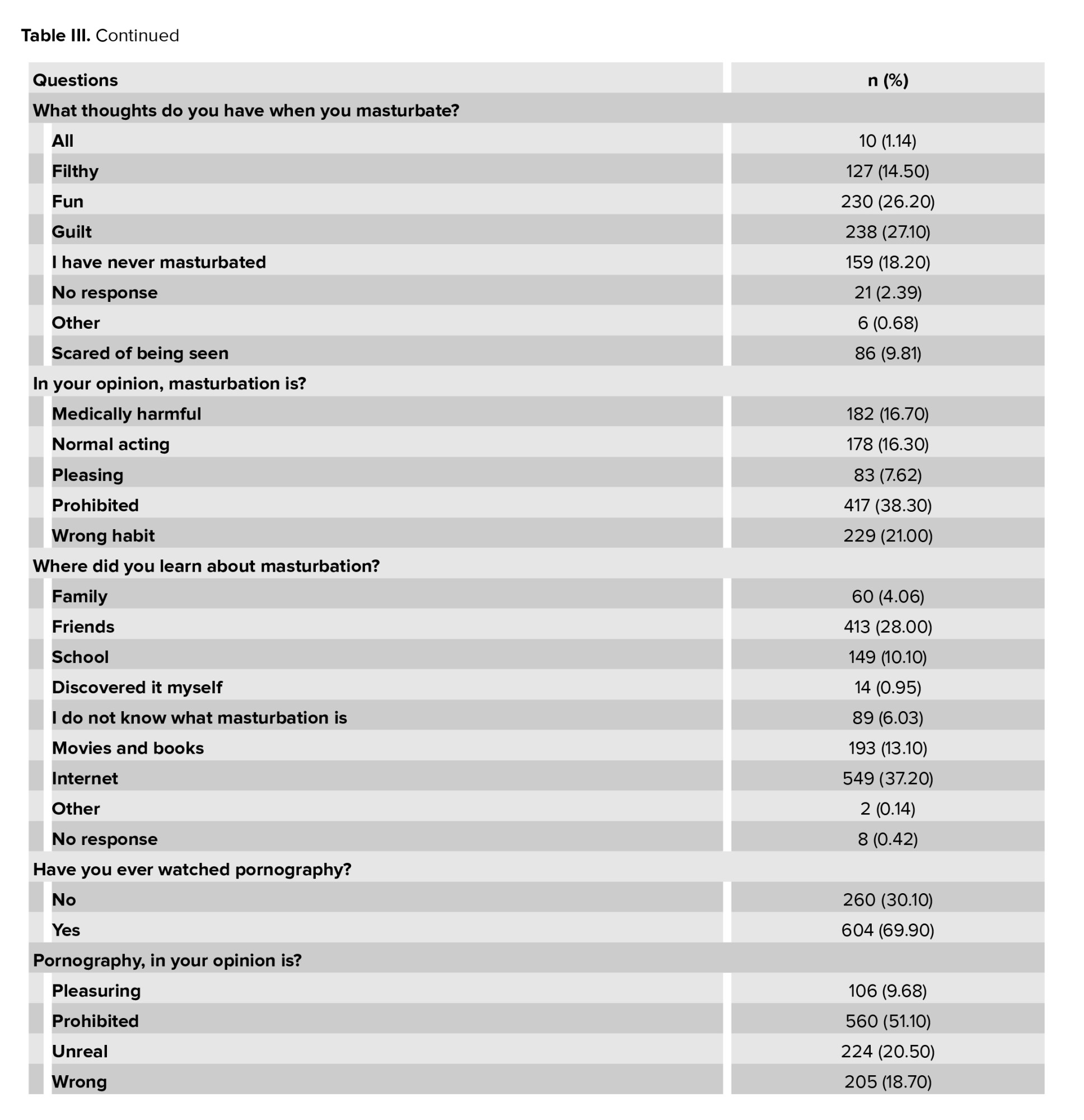

Respondents who knew the meaning of masturbation were 768 (88.9%), of which 203 females and 351 males had practiced masturbation. The Internet was the most commonly reported tool for learning about masturbation, accounting for 549 (63.5%) of all study participants. Among those who masturbate, 28.9% required visual stimulators to masturbate. Feeling guilty upon masturbation was reported in 27.1% of respondents. However, 26.2% feel "fun" during masturbation. On the contrary, 38.3% think masturbation is a prohibited act, 21% believe it is a bad habit, and 16.7% are convinced that it is medically harmful to masturbate. A statistically significant association was found between male gender and pornography exposure (p < 0.001). More than half (51.1%) considered pornography a prohibited act (Table III).

3.4. Sexual intercourse and related presumptions

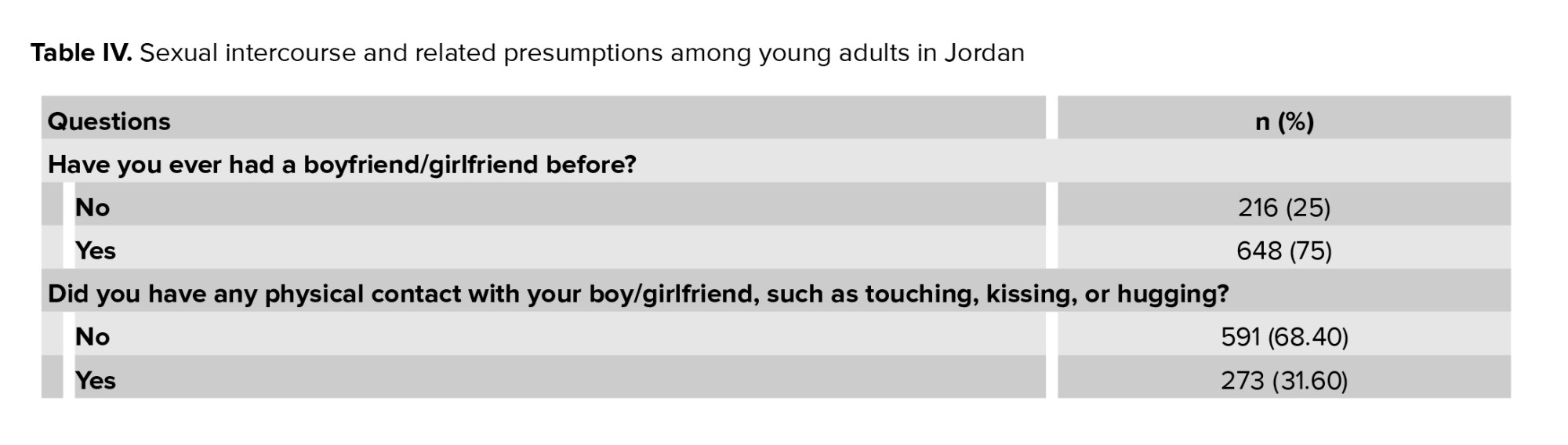

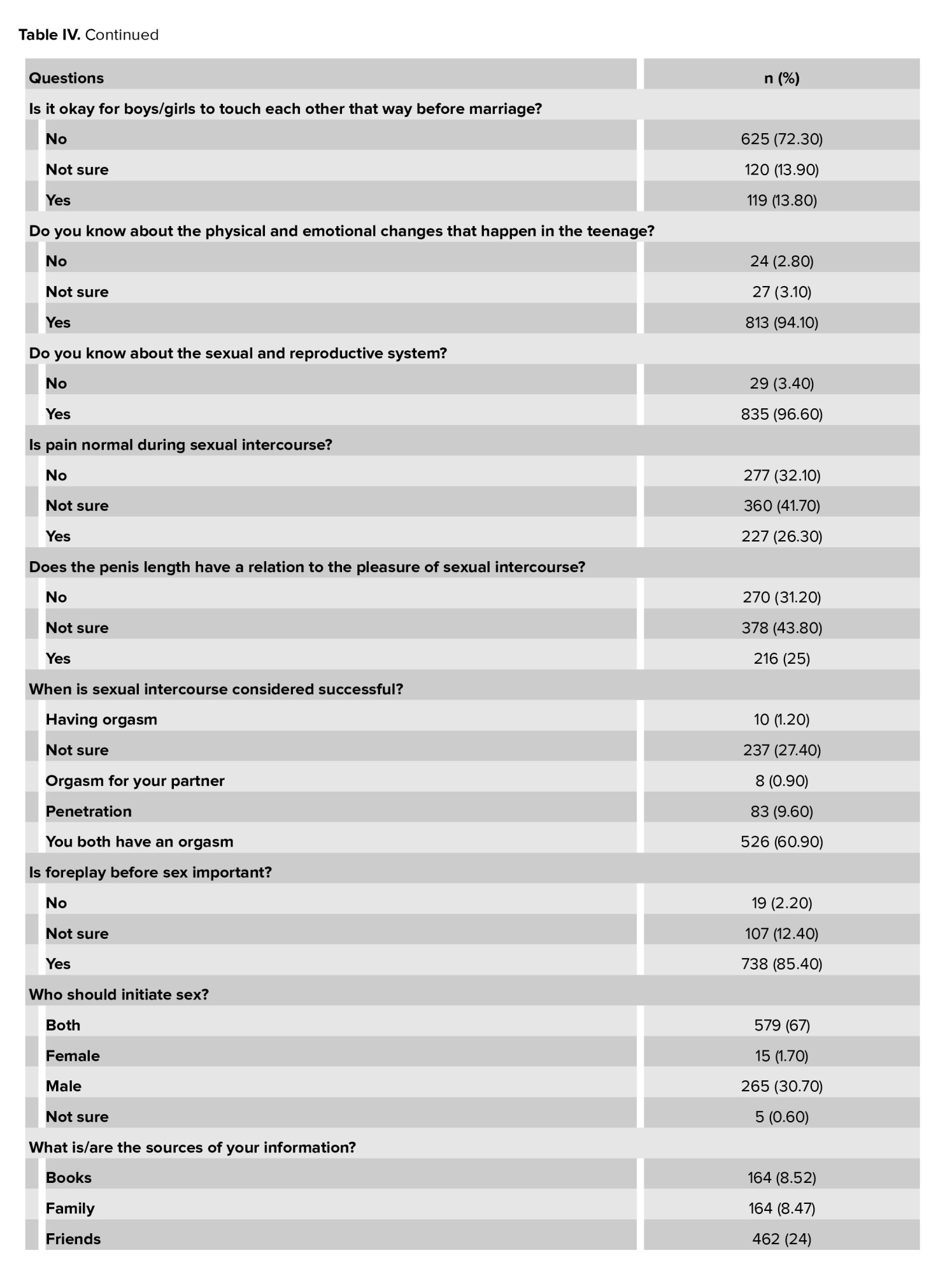

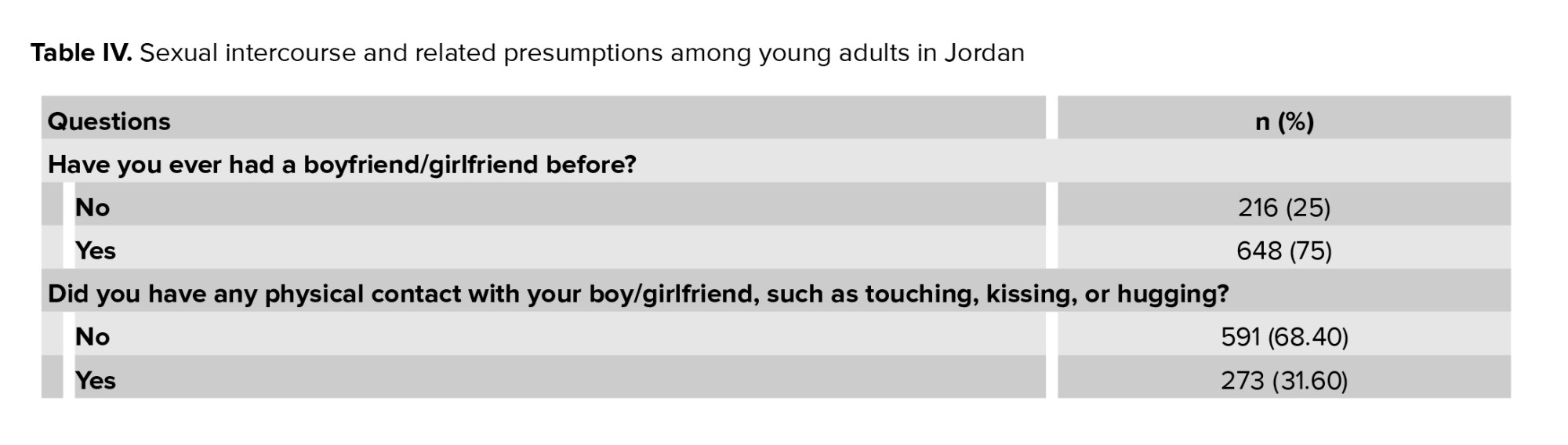

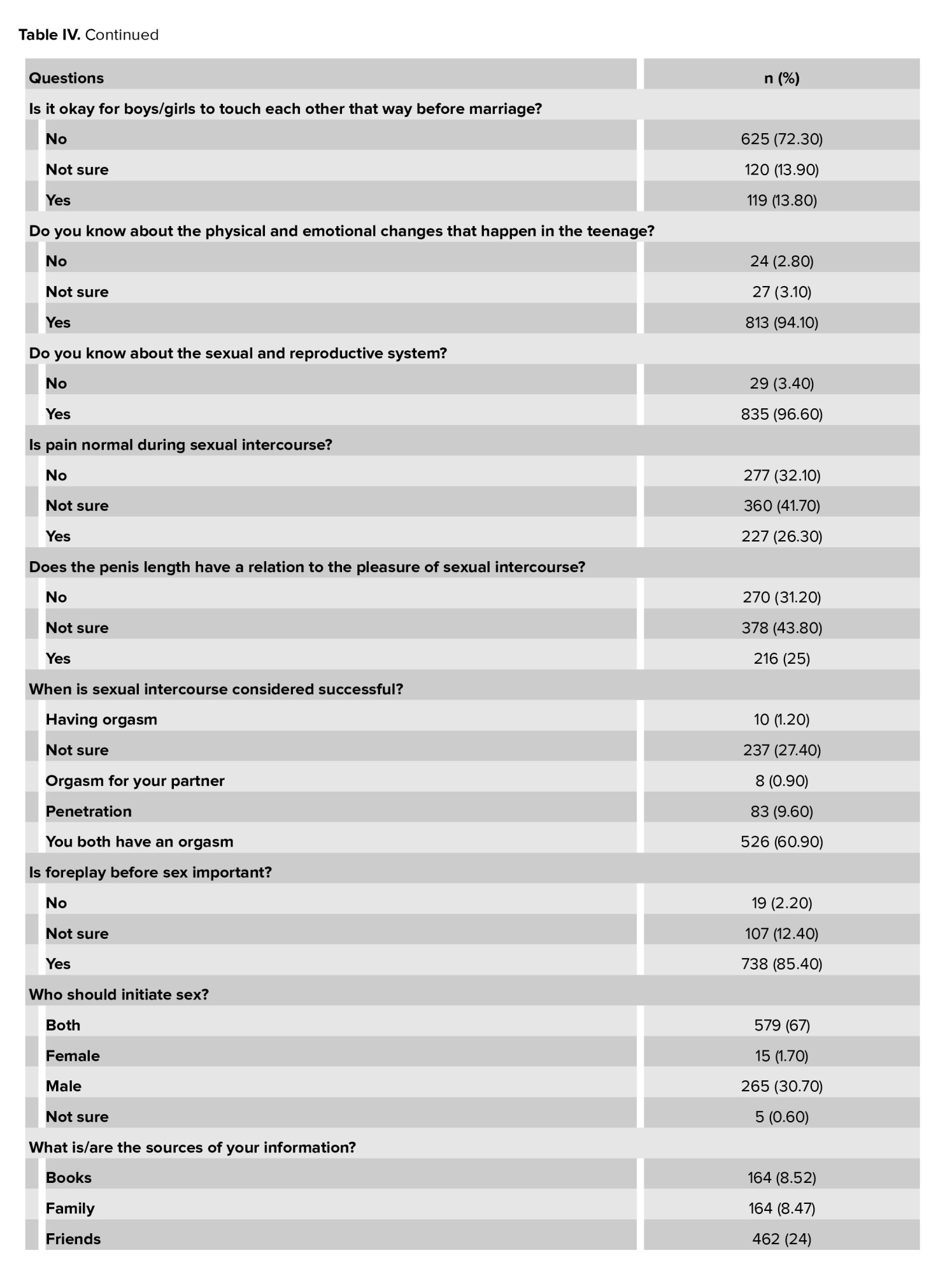

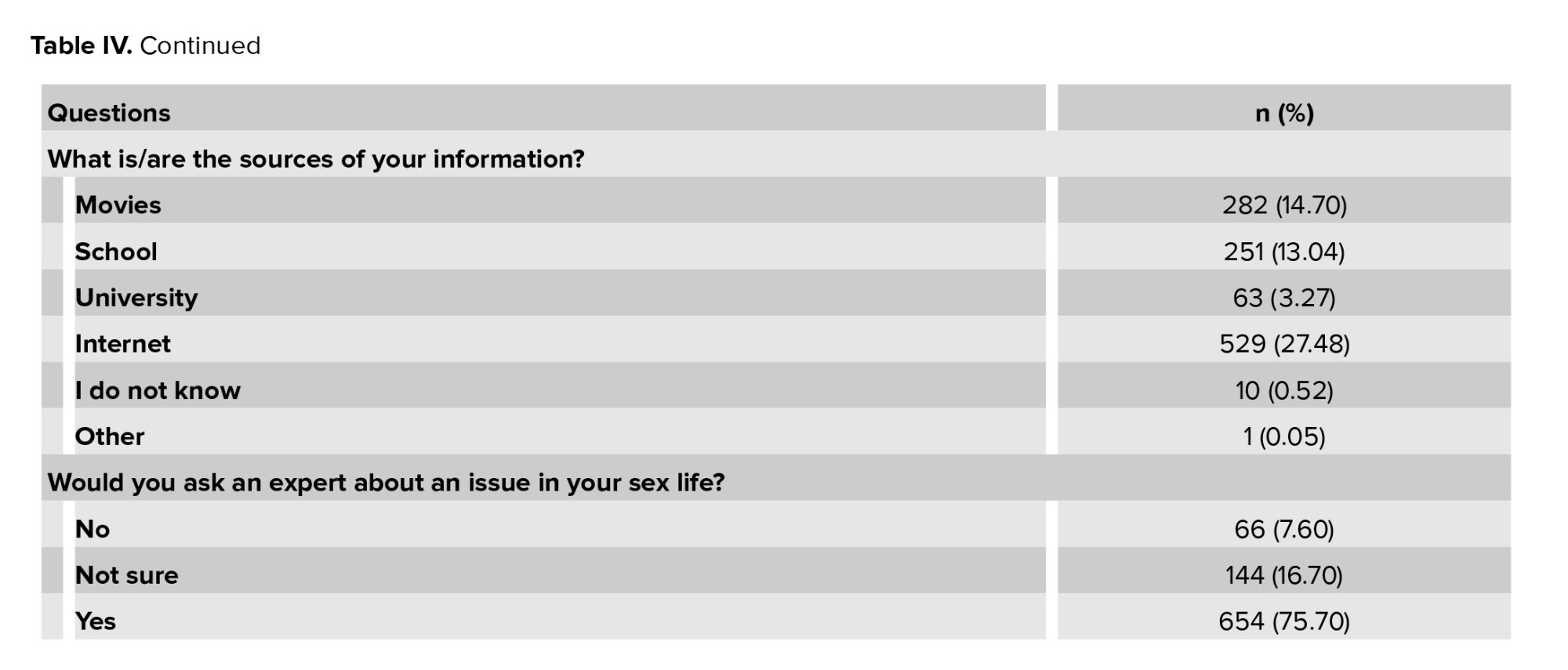

3-quarters of the respondents had been in a relationship (648), and 273 had physical contact with their partners, such as kissing, hugging, or touching. However, 72.3% of all study participants believe it is wrong to pursue physical contact before marriage. The majority of respondents, 813 (94.1%), stated that they are aware of the physical and emotional changes that occur during their teenage years, and 835 (96.6%) are aware of the sexual and reproductive systems. A total of 227 (26.3%) believe the pain in intercourse is normal, and 216 (25%) respondents affirmed that penile length correlates with pleasure during intercourse. Most respondents, 60%, consider sexual intercourse successful when both partners have orgasms. It is presumed that foreplay before initiation of sex is significant among 738 (85.4%) respondents. 67% of respondents agreed that initiating sexual activity is a shared responsibility between partners. Respondents who may seek expert help for issues in their sexual life were 654 (75.7%), but the most common source of obtaining further information was through the internet (Table IV).

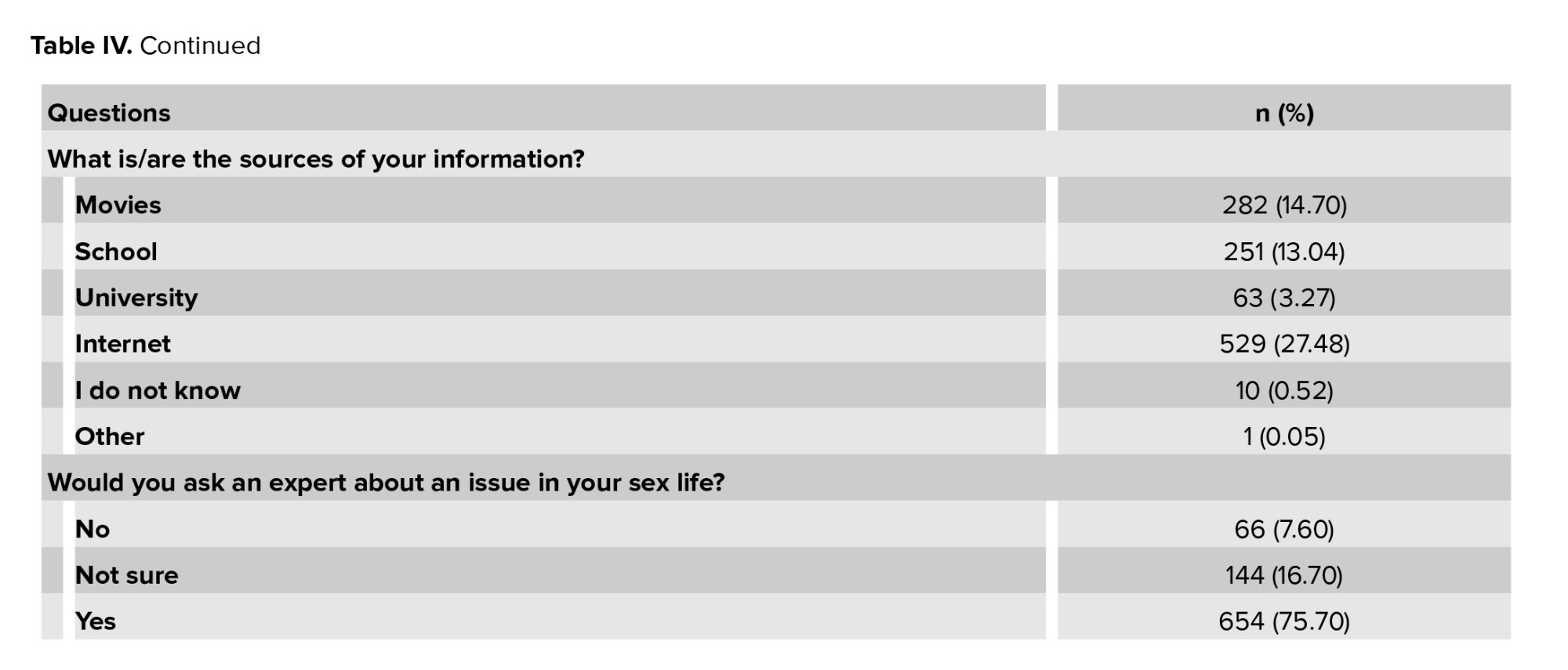

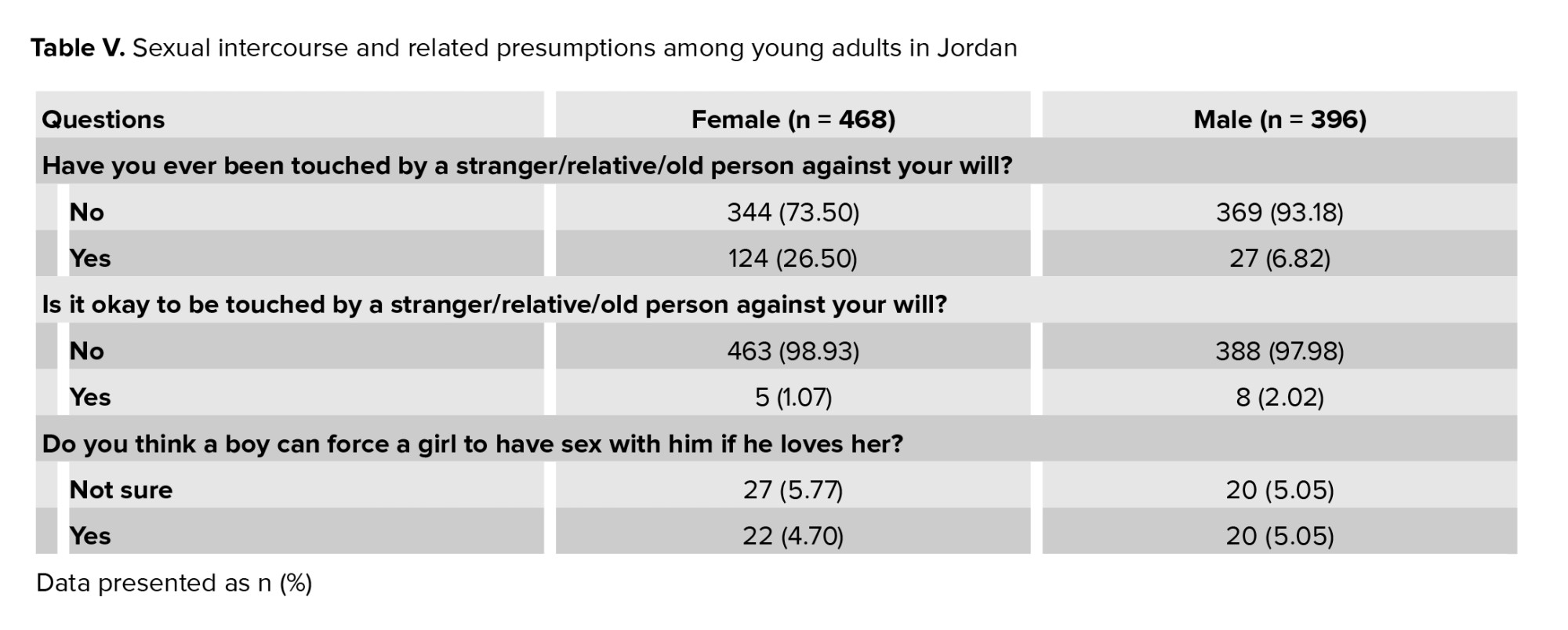

Of the study participants, 151 (17.5%) were molested by an older person, a relative, or a stranger. Fortunately, only 1.5% of all participants think it is acceptable. A significant association was found between gender and experience of unwanted sexual contact Phi (-0.258), p < 0.001, indicating females were significantly more likely to report such experiences. In a similar vein, only 42 (4.9%) respondents believe that a boy can force a lady to have sex with him if he considers he loves her (Table V).

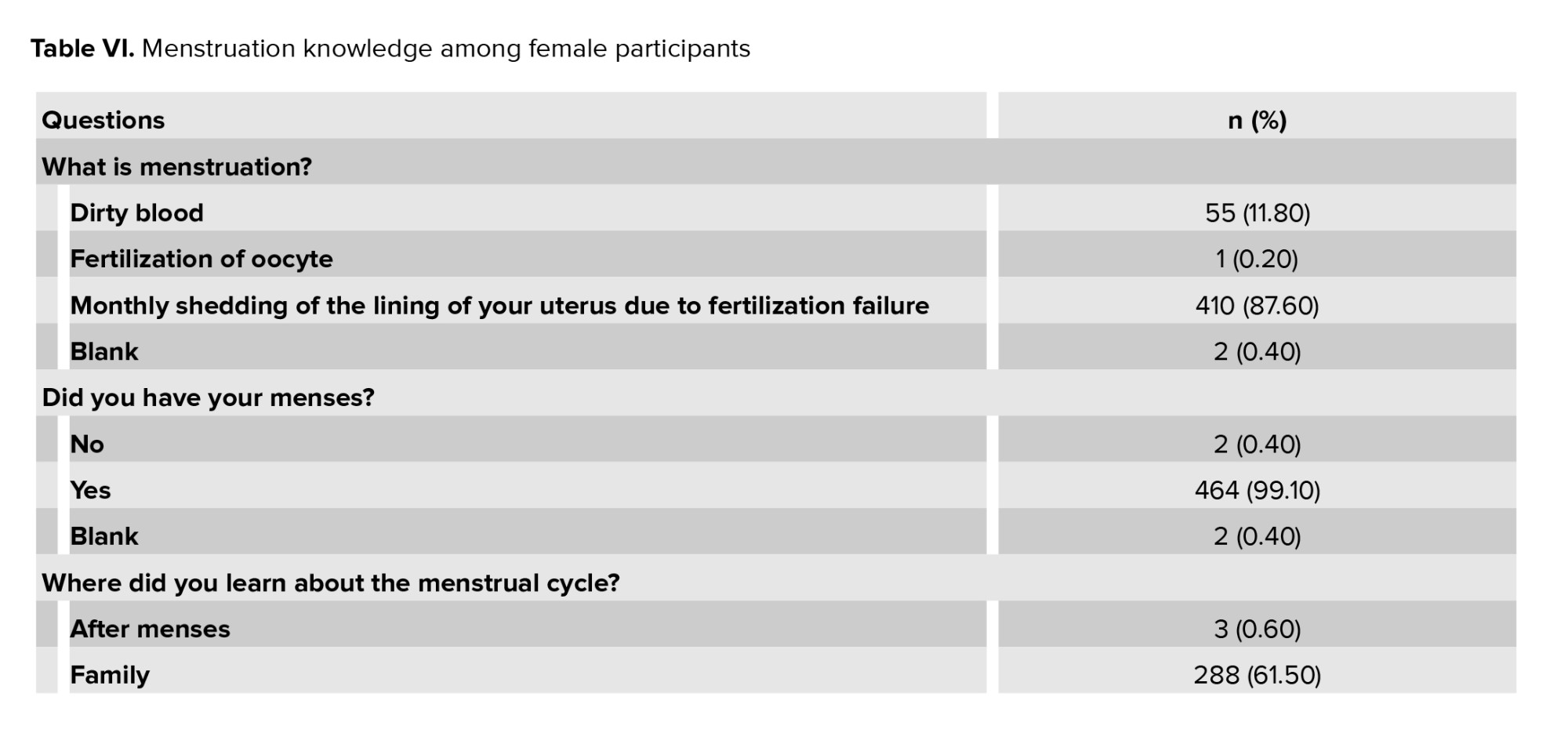

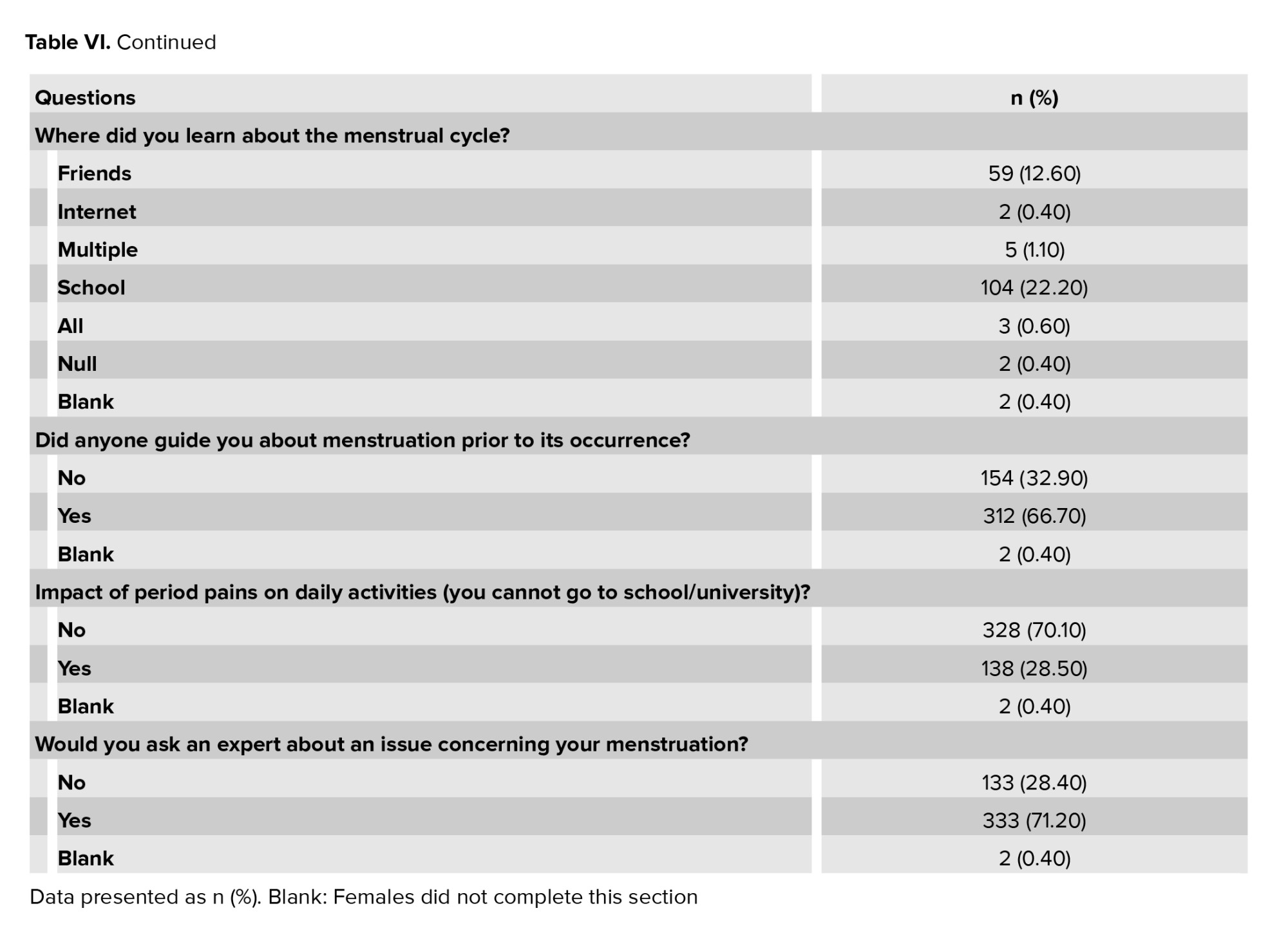

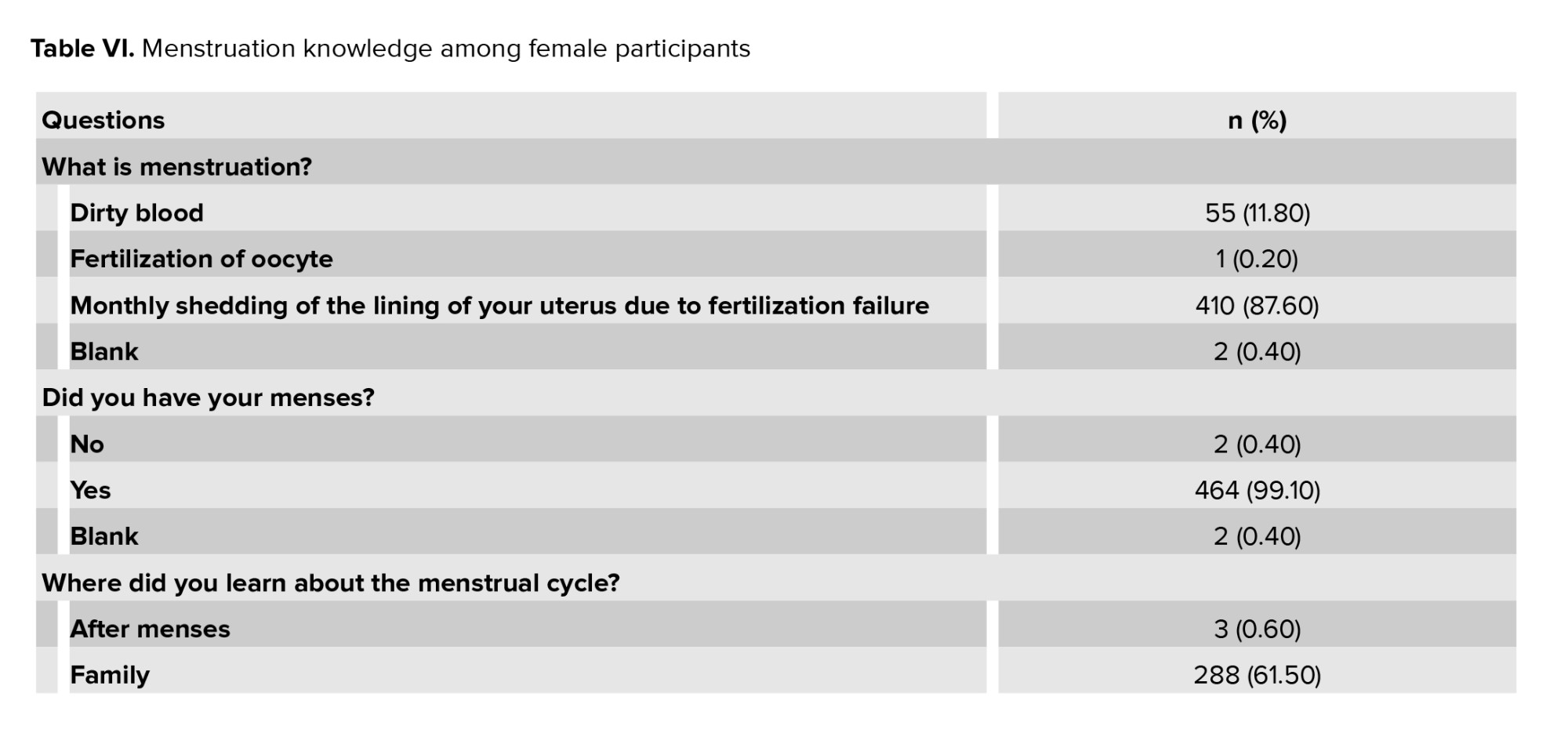

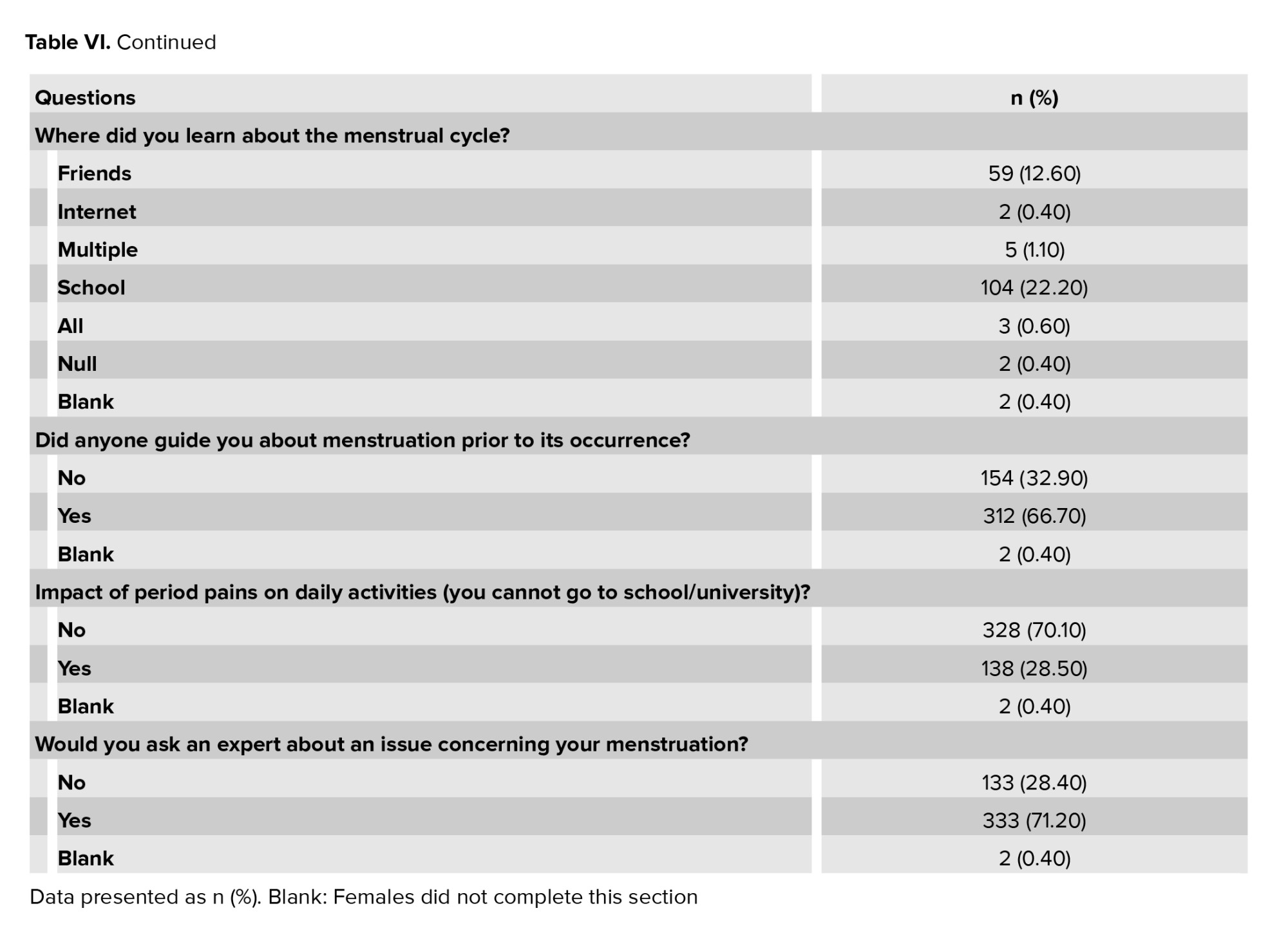

3.5. Menstruation

This set of questions was answered only by female participants. 87.6% of the sample defined menstruation correctly, while 11.8% defined it as "dirty blood", and 0.2% defined it as the fertilization of oocyte, 2 participants did not complete the menstruation part of the survey and were labeled as blank. Out of all the female participants, only 2 females did not have their menses, aged 15 and 18, and 99.1% did. Most learned about the menstrual cycle from their family, 61.5%, while 22.2% learned about it from school, and 66.7% were well informed prior to having their first menses. Around 30% complained about period pains affecting their daily life, and 71.2% were willing to consult a specialist. Complete information has been mentioned in table VI.

When it comes to how the participants deal with period pains, 2 did not answer, and 2 were removed due to not getting their menses yet. As for the rest, 2% had no significant pain, 37% did not use any medications but tried hot beverages, relaxing, and other non-medical remedies, while the rest 61% had to use pain medication.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of the Jordanian youth population toward sexual and reproductive health. The topic is considered an area of stigma among Middle Eastern countries, given the fact that most of these countries are conservative by religion and that sexual education is rarely ever discussed. Consequently, incorrect sexual behaviors continue to exist, leading to possible morbidity in the population, such as the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

Our findings, unexpectedly, did not align with the social norms, as 75% of our respondents were in a relationship before. Along analogous lines, 64.1% have previously masturbated, and 27.1% of them felt guilty about it. In contrast, more females (n = 69) than males (n = 50) are open to physical contact before marriage. Socio-demographic data reflect that living with parents does not affect sexual behaviors, like masturbation or watching pornography. Neither does that delineate optimal sexual expectations or rapport. It is also in consensus with previous research on parental approaches toward masturbation among youth(18) . This is explained by the lack of communication between parents and their children about sexual health, as shown in our study, where only 346 (40%) have discussed puberty, sexual changes, and reproduction with their parents.

Due to the immense prevalence of masturbation, it was and continues to be disputed whether it is an accepted behavior with no adverse effects or whether it is unfavorable and requires public education on how to avoid it(19) . Several research studies have indicated that engaging in masturbation can have adverse effects on physical health. There is also a growing body of evidence suggesting that increased cardiovascular reactivity to stress may lead to hypertension over time. According to Brody et al. penile-vaginal intercourse is associated with an increased body's blood pressure response to stress. At the same time, masturbation not only amplifies blood pressure reactivity to stress but also diminishes the positive effects of penile-vaginal intercourse (20) . Masturbation can have various impacts on the prostate. A study that was done in 2016 revealed that masturbation is linked to elevated levels of prostate-specific antigen in the blood (21) .

Masturbation and pornography can also distort expectations and perceptions of the real marital life. Overexposure to this can create unrealistic ideas of sexual performance and intimacy. This can lead to dissatisfaction and disappointment in relationships. Furthermore, unrealistic expectations set by pornography can hinder the success of marital life. Masturbation and excessive pornography consumption may lead to decreased interest in real intimacy and a struggle to connect with a partner on a deeper level. It can lead to difficulties in achieving satisfaction and fulfillment in a marital relationship. Healthy communication and understanding are crucial for overcoming the ill effects of distorted expectations caused by masturbation and pornography(22) . Despite that, couples can work together to address these issues. However, in such conservative communities, they might find it difficult to build a healthy and fulfilling marital relationship, particularly if professional help is needed due to a lack of good communication between partners and the sensitivity of the topic.

A non-negligible portion of respondents, 151 (17.5%), have been molested. A report on sexual harassment of women in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine has been released by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Its findings are extremely impacting. Sexual harassment is prevalent throughout scientific majors, has not diminished, and is mostly reported in medicine, where potential causes of harassment include not just coworkers and supervisors but also patients and family members. To accentuate a single statistic, up to 50% of female medical students have reported sexual harassment(23) . However, in Arab culture, the coping system of sexual harassment is premature. Discussing the phenomena or a situation openly may be met with cultural constraints. Due to social norms and the fear of stigmatization, many individuals choose not to come forward or report incidents of sexual harassment. The emphasis on preserving family honor and avoiding public shame can discourage victims from seeking justice or speaking out against their perpetrators. This cultural silence perpetuates a cycle of impunity for offenders and can have detrimental effects on the mental and emotional well-being of those who have experienced harassment. Due to the lack of adequate knowledge and awareness about sexual health and reproductive issues, it is possible that instances of sexual harassment may not be perceived as such by the youth population. This emphasizes the critical importance of comprehensive sexual education and awareness programs to address and prevent such misconceptions. Initiating open conversations and challenging these cultural barriers is crucial in addressing and preventing unfavorable consequences.

In terms of menstruation education among the Jordanian youth, 154 respondents have not learned about menstruation before menarche, and 398 refuse to consult a professional concerning their menstrual cycles. Almost all have tried herbal remedies and hot beverages, methods of relaxation, or painkillers to cope with expected discomfort. Moreover, 138 addressed that menstruation has a negative impact on their daily life. During menstruation, it is normal to experience symptoms such as abdominal cramps, bloating, fatigue, and mood swings. These symptoms result from hormonal changes in the body and are generally manageable with self-care and over-the-counter medications. Patient education and open discussions with healthcare providers are crucial in managing premenstrual symptoms and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Individuals experiencing severe symptoms should seek proper diagnosis and management. Treatment options, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, should be carefully considered based on patient-centered needs and symptoms.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

About 6% of respondents were enrolled in middle school. Therefore, our results are not applicable to this age group. Given the nature of the issue and the society in question, some figures provided might be underrepresented. However, by using an anonymous online survey and culturally appropriate (but valid) language when translating the original survey into Arabic, we tried to minimize such bias. We faced some trouble during data collection due to the conservative cultural norms. Future research should use a prospective design to determine the age at which these beliefs and attitudes are formed and to provide proper education and prevention.

Furthermore, cross-cultural research is encouraged to identify the factors that influence sexual views and practices. There is little public data on sexual and reproductive health, including knowledge of sexually transmitted illnesses, unintended pregnancy, and pregnancy termination. Therefore, further research is essential to study the abovementioned areas.

5. Conclusion

It is noted that when it comes to sexual health issues, many Arab and Muslim nations share a conservative culture. However, findings demonstrate significant awareness and openness among Jordanian youth toward sexual education, although cultural barriers still exist. Recommendations include reforming sexual education and encouraging discussions to break taboos. We also propose that taking serious steps regarding sexual harassment is essential. It is mandatory to develop an empowering culture where adolescents are comfortably addressing their sexual health in different social settings, which in return ensures better public sexual and reproductive health.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

L. Almahmoud, L. Altawil, and Y. Shahatit: Contribution to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work and revising it critically. R. Sami, AA. Qatawneh, and ZM. Alkhdaire: Contribution to the data interpretation, drafting of the work, and critical revision. R. Zurikat, AM. Karmoul, A. Abuawad, W. Al-Dalabeeh, and M. Abu Khait: Contribution to the interpretation and analysis of the data, drafting of the work. M. Bani Hani: Contribution to the conception and design of the work, critical revision, and final editing of the manuscript. The authors, L. Almahmoud, L. Altawil, and Y. Shahatit contributed equally to the work and should be considered co-first authors. All authors bear full responsibility for the content published in this article and approve the final version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ebraheem Albazee, Dr. Noor Adeen AbuSalameh, Dr. Shada Ajarmeh, Dr. Sara Alkahder, and Dr. Yasmeen Qadoume for their role in technical problem solving. This study was not financially supported. We declare no use of artificial intelligence in any way in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Adolescents comprise approximately 16% of the global population

Pubertal health encompasses concepts that have contributed to the improvement of both physical and psychological health

Youth who engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as early sexual initiation, unprotected intercourse, and multiple sexual partners, pose serious and risky consequences, including unwanted pregnancies, abortions, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as HIV, and even death

Recently, the age of puberty onset has declined, mainly due to improved nutrition and overall well-being. This earlier maturation is linked to an earlier initiation of sexual activity, which increases the risk of reproductive and sexual health issues, such as unprotected sex, early marriage, multiple sexual partnerships, and STIs like human papillomavirus and HIV

Furthermore, due to social and cultural restrictions, stigma, and the misconception that discussing sexual health might lead to increased premarital sexual activity, parents, the media, and educational programs are failing to provide adequate information on sexual health

Given the importance of promoting sexual and reproductive health awareness among this age group, we conducted this study to assess Jordanian adolescents' attitudes and knowledge regarding sexual education and sexual and reproductive well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

During the process of preparing this study, we followed the STROBE guidelines

2.1. Sampling, population, and study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January to April, 2024. Our inclusion criteria were Jordanian youth aged 15-22 yr old who consented to participate. Respondents were assembled via opportunity (convenience) sampling. Individuals who did not fit our specified criteria were excluded from the study.

2.2. Study questionnaire and data collection

We utilized a validated, online, pilot-tested, and self-administered survey that was distributed through social media (Facebook and WhatsApp). Our research team adopted the survey after conducting thorough research in databases to find a similar survey used in a previous study conducted in Egypt

The questionnaire was piloted on 80 adolescents between 15 and 25 yr old representing different economic and cultural classes. We distributed the questionnaire to potential participants through social media platforms to ensure maximum participant reach.

The questionnaire was then uploaded to Google Forms after being translated from English to Arabic, and the Arabic questionnaire was validated.

The final questionnaire had 43 items total, split into 2 parts: 10 questions about the respondent's sociodemographic information were included in the first part, and 33 questions about knowledge and attitudes were included in the second part. The second part was divided into 4 sections: masturbation, sexual education, sexual intercourse and related presumptions, and pornography. There was a section at the end of the questionnaire, only for female respondents about menstruation knowledge and attitudes.

2.3. Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft® Software, with a margin error of 5%, confidence interval of 99%, response distribution of 50%, and a population of 10 million, yielding at least 664 respondents. As a result, 864 people were surveyed.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan (No.20/6/2021/2022). The first section of the questionnaire provided details about the study, including its purpose, the intended group of respondents, and information about the survey. Following this, respondents were asked to indicate their consent to participate in the survey. Their responses were completely confidential.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, we utilized IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 25, Chicago, IL, USA. Means and standard deviations were used to characterize numerical variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were used to characterize categorical variables.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic data

A total of 864 adolescents aged between 15 and 22 participated, of whom 54.2% (n = 468) were women and 45.8% (n = 396) were men. The majority of respondents were single, 769 (89%), and only 95 (11%) were in a relationship, of which 18 (2.1%) were married. University students comprised 574 of the respondents (66.4%), 233 (27%) completed secondary school, and only 20 (2.3%) are still in middle school. Most respondents reside in an urban area with their parents (Table I).

3.2. Sexual education and complementary attitudes

Sexual education is presumed necessary in 623 (72.1%), 136 (15.7%) respondents find that it contradicts cultural beliefs, 79 (9.1%) are not sure, and 26 (3%) think it is not important. 663 (76.7%) respondents advocate for sexual education in schools. However, only 491 (56.8%) have learned about male and female reproductive systems at school. Males were more likely than females to report confidence discussing sexual health in educational settings (46.7% vs. 35.7%). Additionally, 216 females and 130 males have ever discussed matters like puberty, sexual changes, or pregnancy with either parent. Most respondents, accounting for 583 (67.5%), believe that sexual and reproductive health education does not contradict religious beliefs. Table II shows more details on sexual education and complementary attitudes.

3.3. Masturbation and pornography

Respondents who knew the meaning of masturbation were 768 (88.9%), of which 203 females and 351 males had practiced masturbation. The Internet was the most commonly reported tool for learning about masturbation, accounting for 549 (63.5%) of all study participants. Among those who masturbate, 28.9% required visual stimulators to masturbate. Feeling guilty upon masturbation was reported in 27.1% of respondents. However, 26.2% feel "fun" during masturbation. On the contrary, 38.3% think masturbation is a prohibited act, 21% believe it is a bad habit, and 16.7% are convinced that it is medically harmful to masturbate. A statistically significant association was found between male gender and pornography exposure (p < 0.001). More than half (51.1%) considered pornography a prohibited act (Table III).

3.4. Sexual intercourse and related presumptions

3-quarters of the respondents had been in a relationship (648), and 273 had physical contact with their partners, such as kissing, hugging, or touching. However, 72.3% of all study participants believe it is wrong to pursue physical contact before marriage. The majority of respondents, 813 (94.1%), stated that they are aware of the physical and emotional changes that occur during their teenage years, and 835 (96.6%) are aware of the sexual and reproductive systems. A total of 227 (26.3%) believe the pain in intercourse is normal, and 216 (25%) respondents affirmed that penile length correlates with pleasure during intercourse. Most respondents, 60%, consider sexual intercourse successful when both partners have orgasms. It is presumed that foreplay before initiation of sex is significant among 738 (85.4%) respondents. 67% of respondents agreed that initiating sexual activity is a shared responsibility between partners. Respondents who may seek expert help for issues in their sexual life were 654 (75.7%), but the most common source of obtaining further information was through the internet (Table IV).

Of the study participants, 151 (17.5%) were molested by an older person, a relative, or a stranger. Fortunately, only 1.5% of all participants think it is acceptable. A significant association was found between gender and experience of unwanted sexual contact Phi (-0.258), p < 0.001, indicating females were significantly more likely to report such experiences. In a similar vein, only 42 (4.9%) respondents believe that a boy can force a lady to have sex with him if he considers he loves her (Table V).

3.5. Menstruation

This set of questions was answered only by female participants. 87.6% of the sample defined menstruation correctly, while 11.8% defined it as "dirty blood", and 0.2% defined it as the fertilization of oocyte, 2 participants did not complete the menstruation part of the survey and were labeled as blank. Out of all the female participants, only 2 females did not have their menses, aged 15 and 18, and 99.1% did. Most learned about the menstrual cycle from their family, 61.5%, while 22.2% learned about it from school, and 66.7% were well informed prior to having their first menses. Around 30% complained about period pains affecting their daily life, and 71.2% were willing to consult a specialist. Complete information has been mentioned in table VI.

When it comes to how the participants deal with period pains, 2 did not answer, and 2 were removed due to not getting their menses yet. As for the rest, 2% had no significant pain, 37% did not use any medications but tried hot beverages, relaxing, and other non-medical remedies, while the rest 61% had to use pain medication.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of the Jordanian youth population toward sexual and reproductive health. The topic is considered an area of stigma among Middle Eastern countries, given the fact that most of these countries are conservative by religion and that sexual education is rarely ever discussed. Consequently, incorrect sexual behaviors continue to exist, leading to possible morbidity in the population, such as the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

Our findings, unexpectedly, did not align with the social norms, as 75% of our respondents were in a relationship before. Along analogous lines, 64.1% have previously masturbated, and 27.1% of them felt guilty about it. In contrast, more females (n = 69) than males (n = 50) are open to physical contact before marriage. Socio-demographic data reflect that living with parents does not affect sexual behaviors, like masturbation or watching pornography. Neither does that delineate optimal sexual expectations or rapport. It is also in consensus with previous research on parental approaches toward masturbation among youth

Due to the immense prevalence of masturbation, it was and continues to be disputed whether it is an accepted behavior with no adverse effects or whether it is unfavorable and requires public education on how to avoid it

Masturbation and pornography can also distort expectations and perceptions of the real marital life. Overexposure to this can create unrealistic ideas of sexual performance and intimacy. This can lead to dissatisfaction and disappointment in relationships. Furthermore, unrealistic expectations set by pornography can hinder the success of marital life. Masturbation and excessive pornography consumption may lead to decreased interest in real intimacy and a struggle to connect with a partner on a deeper level. It can lead to difficulties in achieving satisfaction and fulfillment in a marital relationship. Healthy communication and understanding are crucial for overcoming the ill effects of distorted expectations caused by masturbation and pornography

A non-negligible portion of respondents, 151 (17.5%), have been molested. A report on sexual harassment of women in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine has been released by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Its findings are extremely impacting. Sexual harassment is prevalent throughout scientific majors, has not diminished, and is mostly reported in medicine, where potential causes of harassment include not just coworkers and supervisors but also patients and family members. To accentuate a single statistic, up to 50% of female medical students have reported sexual harassment

In terms of menstruation education among the Jordanian youth, 154 respondents have not learned about menstruation before menarche, and 398 refuse to consult a professional concerning their menstrual cycles. Almost all have tried herbal remedies and hot beverages, methods of relaxation, or painkillers to cope with expected discomfort. Moreover, 138 addressed that menstruation has a negative impact on their daily life. During menstruation, it is normal to experience symptoms such as abdominal cramps, bloating, fatigue, and mood swings. These symptoms result from hormonal changes in the body and are generally manageable with self-care and over-the-counter medications. Patient education and open discussions with healthcare providers are crucial in managing premenstrual symptoms and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Individuals experiencing severe symptoms should seek proper diagnosis and management. Treatment options, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, should be carefully considered based on patient-centered needs and symptoms.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

About 6% of respondents were enrolled in middle school. Therefore, our results are not applicable to this age group. Given the nature of the issue and the society in question, some figures provided might be underrepresented. However, by using an anonymous online survey and culturally appropriate (but valid) language when translating the original survey into Arabic, we tried to minimize such bias. We faced some trouble during data collection due to the conservative cultural norms. Future research should use a prospective design to determine the age at which these beliefs and attitudes are formed and to provide proper education and prevention.

Furthermore, cross-cultural research is encouraged to identify the factors that influence sexual views and practices. There is little public data on sexual and reproductive health, including knowledge of sexually transmitted illnesses, unintended pregnancy, and pregnancy termination. Therefore, further research is essential to study the abovementioned areas.

5. Conclusion

It is noted that when it comes to sexual health issues, many Arab and Muslim nations share a conservative culture. However, findings demonstrate significant awareness and openness among Jordanian youth toward sexual education, although cultural barriers still exist. Recommendations include reforming sexual education and encouraging discussions to break taboos. We also propose that taking serious steps regarding sexual harassment is essential. It is mandatory to develop an empowering culture where adolescents are comfortably addressing their sexual health in different social settings, which in return ensures better public sexual and reproductive health.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

L. Almahmoud, L. Altawil, and Y. Shahatit: Contribution to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work and revising it critically. R. Sami, AA. Qatawneh, and ZM. Alkhdaire: Contribution to the data interpretation, drafting of the work, and critical revision. R. Zurikat, AM. Karmoul, A. Abuawad, W. Al-Dalabeeh, and M. Abu Khait: Contribution to the interpretation and analysis of the data, drafting of the work. M. Bani Hani: Contribution to the conception and design of the work, critical revision, and final editing of the manuscript. The authors, L. Almahmoud, L. Altawil, and Y. Shahatit contributed equally to the work and should be considered co-first authors. All authors bear full responsibility for the content published in this article and approve the final version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ebraheem Albazee, Dr. Noor Adeen AbuSalameh, Dr. Shada Ajarmeh, Dr. Sara Alkahder, and Dr. Yasmeen Qadoume for their role in technical problem solving. This study was not financially supported. We declare no use of artificial intelligence in any way in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Epidemiology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |