Wed, Jan 28, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 10 (October 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(10): 775-786 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Alaei A, Azizi M M, Homayoun M. Diabetes and male infertility: A review of sperm chromatin damage and epigenetic effects. IJRM 2025; 23 (10) :775-786

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3596-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3596-en.html

1- Department of Anatomical and Molecular Biology Sciences, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Medical Physics, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Anatomical and Molecular Biology Sciences, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,homayoun.m@med.mui.ac.ir

2- Department of Medical Physics, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Anatomical and Molecular Biology Sciences, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 819 kb]

(547 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (413 Views)

Full-Text: (2 Views)

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has become a global health crisis, with prevalence skyrocketing from 108 million in 1980 to 463 million in 2019 (1, 2). DM is a category of metabolic dysfunctions defined by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, function, or both (3). The primary forms are type 1 (autoimmune insulin deficiency), type 2 (cellular insulin resistance), and gestational diabetes (temporary pregnancy-induced resistance) (4-7). This condition causes long-term damage, dysfunction, and failure of various organs (8), driven by a combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors that sustain a hyperglycemic state (9). Uncontrolled hyperglycemia generates reactive free radicals, leading to devastating micro- and macrovascular complications, a systemic inflammatory status, and reduced life expectancy (10).

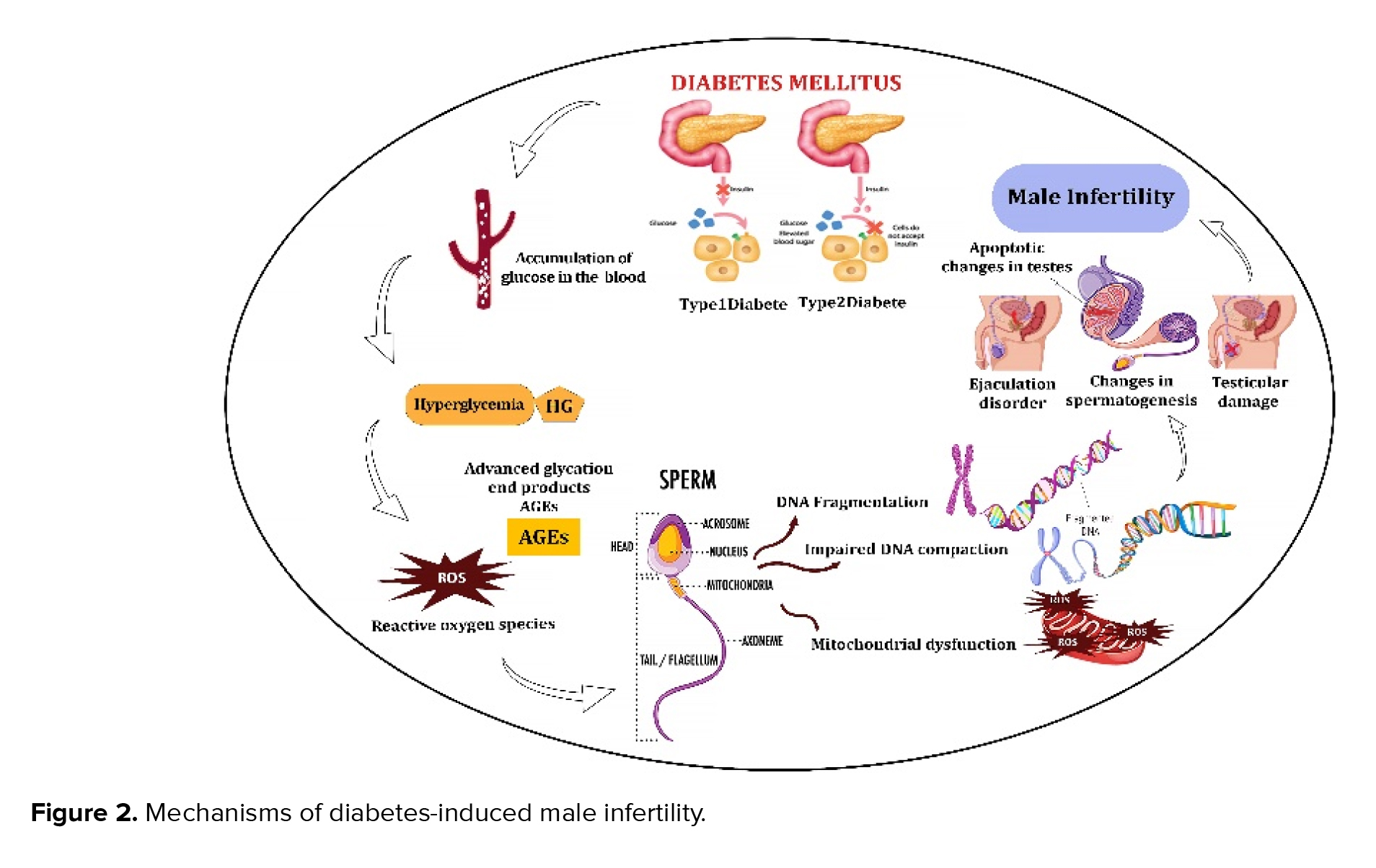

This metabolic imbalance, characterized by overproduction of oxidative molecules and impaired antioxidant defenses, poses a significant threat to physiological homeostasis. Consequently, the reproductive systems of diabetic individuals are highly vulnerable to dysfunction (11). Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) exert direct and indirect detrimental effects across the entire reproductive system. This includes alterations to the central hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, as well as the testes, epididymis, and accessory glands (12). Research demonstrates that diabetes impairs male fertility through multiple mechanisms, including disrupted sperm production, testicular apoptosis, altered glucose metabolism at the blood-testis barrier, reduced testosterone, ejaculatory difficulties, and decreased libido (13-15).

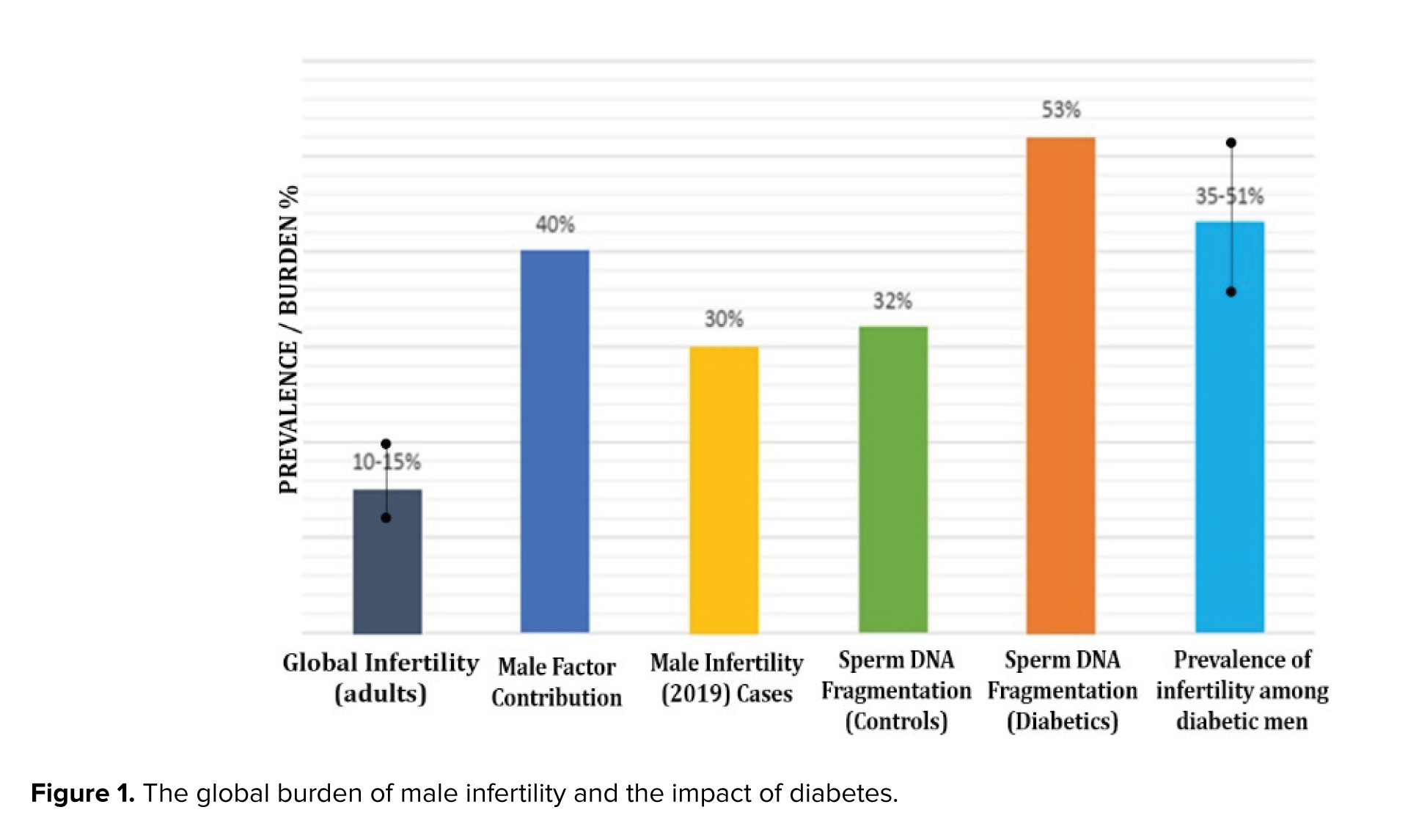

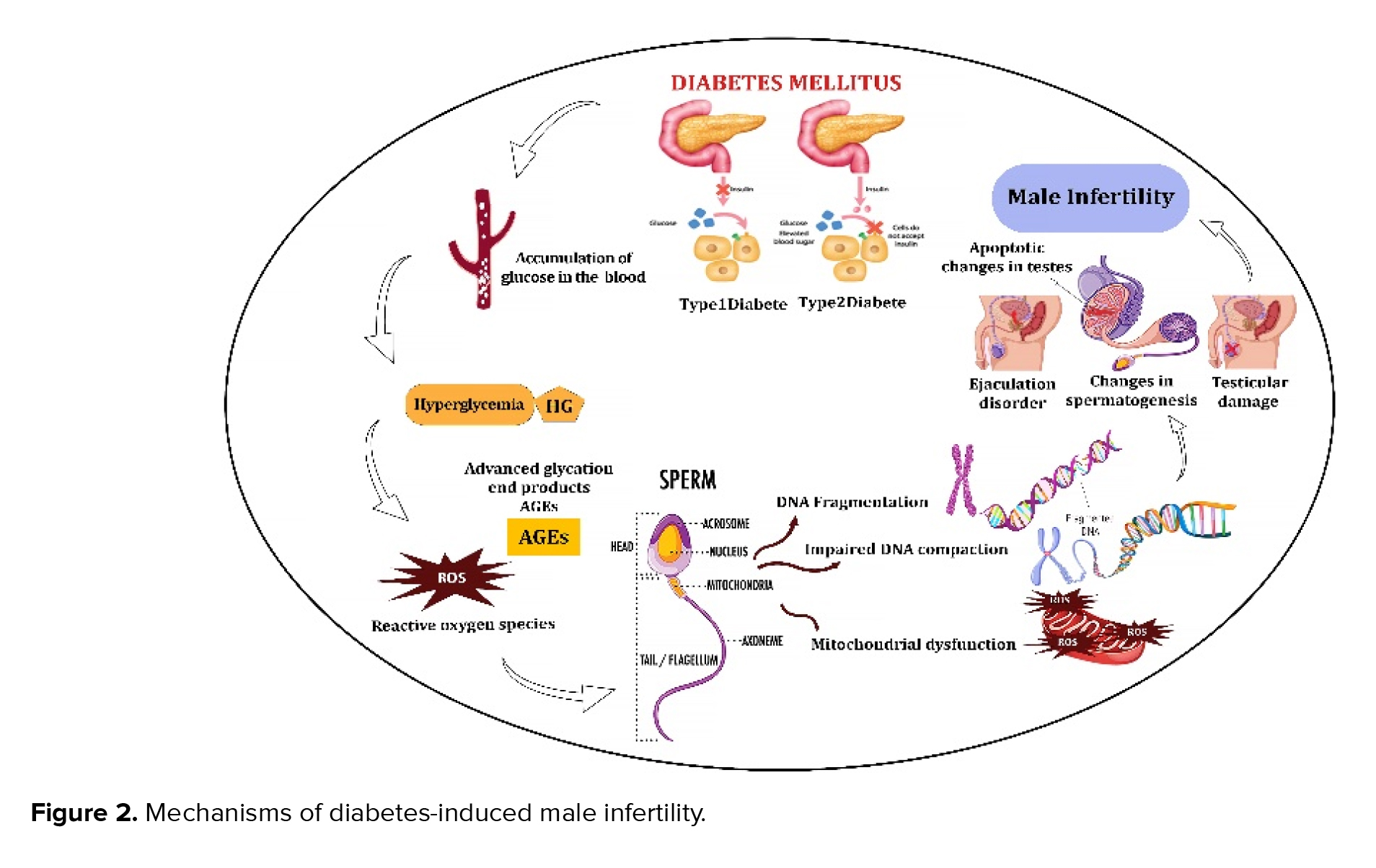

Critically, diabetes adversely affects male fertility by impairing sperm characteristics and significantly increasing sperm DNA fragmentation, a key consequence of disrupted glucose metabolism in spermatogenesis (16, 17). Figure 1 summarizes global statistics on the impact of diabetes on male infertility. Infertility affects 10-15% of couples, with the male factor being the cause in approximately 40% of cases. This problem is intensified by diabetes, which contributes to infertility rates ranging from 35-51% in men with the condition. A crucial mechanistic pathway for this is a substantially higher sperm DNA fragmentation, which is found in 53% of men with diabetes compared to only 32% of healthy men (18-20).

Furthermore, epigenetic modifications, such as aberrant DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and non-coding RNA expression can compromise sperm quality and have consequences extending beyond conception. These alterations can negatively affect embryonic development and the metabolic health of offspring (21, 22). These altered epigenetic profiles not only undermine fertilization potential but also risk being transmitted to subsequent generations, increasing the incidence of metabolic and developmental disorders (23). The concept of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance is crucial, as environmentally-induced epigenetic changes during critical developmental windows can become permanently established in the germline, with long-term health repercussions for future descendants (24, 25).

Given the rising prevalence of diabetes in reproductive-aged men and its detrimental impact on fertility, this review aims to elucidate the mechanisms by which DM compromises sperm chromatin integrity and induces epigenetic modifications. It will detail standard sperm chromatin structure, the pathological effects of its alteration, and the specific diabetic pathways causing damage. The influence of treatments and future research directions will also be evaluated.

2. Methodology

This metabolic imbalance, characterized by overproduction of oxidative molecules and impaired antioxidant defenses, poses a significant threat to physiological homeostasis. Consequently, the reproductive systems of diabetic individuals are highly vulnerable to dysfunction (11). Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) exert direct and indirect detrimental effects across the entire reproductive system. This includes alterations to the central hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, as well as the testes, epididymis, and accessory glands (12). Research demonstrates that diabetes impairs male fertility through multiple mechanisms, including disrupted sperm production, testicular apoptosis, altered glucose metabolism at the blood-testis barrier, reduced testosterone, ejaculatory difficulties, and decreased libido (13-15).

Critically, diabetes adversely affects male fertility by impairing sperm characteristics and significantly increasing sperm DNA fragmentation, a key consequence of disrupted glucose metabolism in spermatogenesis (16, 17). Figure 1 summarizes global statistics on the impact of diabetes on male infertility. Infertility affects 10-15% of couples, with the male factor being the cause in approximately 40% of cases. This problem is intensified by diabetes, which contributes to infertility rates ranging from 35-51% in men with the condition. A crucial mechanistic pathway for this is a substantially higher sperm DNA fragmentation, which is found in 53% of men with diabetes compared to only 32% of healthy men (18-20).

Furthermore, epigenetic modifications, such as aberrant DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and non-coding RNA expression can compromise sperm quality and have consequences extending beyond conception. These alterations can negatively affect embryonic development and the metabolic health of offspring (21, 22). These altered epigenetic profiles not only undermine fertilization potential but also risk being transmitted to subsequent generations, increasing the incidence of metabolic and developmental disorders (23). The concept of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance is crucial, as environmentally-induced epigenetic changes during critical developmental windows can become permanently established in the germline, with long-term health repercussions for future descendants (24, 25).

Given the rising prevalence of diabetes in reproductive-aged men and its detrimental impact on fertility, this review aims to elucidate the mechanisms by which DM compromises sperm chromatin integrity and induces epigenetic modifications. It will detail standard sperm chromatin structure, the pathological effects of its alteration, and the specific diabetic pathways causing damage. The influence of treatments and future research directions will also be evaluated.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across major scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, to identify studies examining the impact of DM on male fertility.

Keywords used in the search included "diabetes mellitus", "male infertility", "sperm chromatin structure", "DNA fragmentation", and "epigenetics". The search covered studies published between 2000 and 2025 to capture recent advances. Both human and animal model studies were included to provide a broad perspective on the mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced sperm chromatin damage and epigenetic alterations. Inclusion criteria comprised original research articles and reviews that specifically addressed diabetes-associated changes in sperm chromatin integrity, DNA integrity, and epigenetic modifications. Exclusion criteria included studies not available in English, those lacking clear methodology, or articles focused on female fertility or unrelated topics. The selected literature was critically appraised to synthesize current knowledge on the effects of DM on male reproductive health.

3. Main body

3.1. Chromatin structure of human spermatozoa

Keywords used in the search included "diabetes mellitus", "male infertility", "sperm chromatin structure", "DNA fragmentation", and "epigenetics". The search covered studies published between 2000 and 2025 to capture recent advances. Both human and animal model studies were included to provide a broad perspective on the mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced sperm chromatin damage and epigenetic alterations. Inclusion criteria comprised original research articles and reviews that specifically addressed diabetes-associated changes in sperm chromatin integrity, DNA integrity, and epigenetic modifications. Exclusion criteria included studies not available in English, those lacking clear methodology, or articles focused on female fertility or unrelated topics. The selected literature was critically appraised to synthesize current knowledge on the effects of DM on male reproductive health.

3. Main body

3.1. Chromatin structure of human spermatozoa

The sperm chromatin structure is a uniquely compacted and highly organized form of DNA packaging, essential for the protection and transmission of the paternal genome to the oocyte (26). In human sperm, the chromatin includes 3 significant structural areas, most of which are binded to protamine and are arranged in toroids (27), and a smaller segment binds to histones (28). The initial expression of nuclear packaging proteins, including protamines and transition proteins, takes place during the process of spermiogenesis (29). Protamines contain some cysteines forming intermolecular disulfide bridges, which become more prevalent during epididymal transport and lead to greater stability of the sperm chromatin structure. In vitro sperm decondensation, achieved through the use of reducing reagents, is employed to regulate the process of fertilization (30-32). Protamine binding plays a crucial role in inhibiting gene expression throughout spermatogenesis; however, its function in fertilization and the stages that follow are likely to provide protection. The protective effect of protamine binding was also confirmed in a study in which mouse sperm were briefly treated with ultrasound before being injected into oocytes (33).

3.2. Effect of sperm chromatin structures on male infertility

3.2. Effect of sperm chromatin structures on male infertility

The population of spermatozoa at the time of ejaculation can be very different. This variability is apparently more pronounced in patients exhibiting sperm parameters lower than standard values. The fact that low sperm quality is associated with DNA damage in spermatozoa indicates intrinsic spermatogenic defects in particular patients (33). Gene mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, and environmental stress can interfere with the biochemical processes occurring during spermatogenesis, potentially leading to an abnormal chromatin structure that impairs fertility (34).

Previous studies have shown that the DNA integrity of spermatozoa is needed for normal fertilization and inheritance of paternal genes in offspring (35, 36). Moreover, the sperm plasma membrane has lipids as polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are sensitive to damage by ROS, resulting in lipid peroxidation (37, 38). Abnormal sperm chromatin packaging may lead to complications through various mechanisms. For instance, inadequate condensation and stabilization of the chromatin results in the DNA being more vulnerable (39). Conversely, excessive compaction of the sperm chromatin can delay the proper timing for the rapid transfer of the sperm DNA into the ooplasm. Therefore, it's critical to consider any factors that disrupt the normal compaction of sperm chromatin -either decrease or increase- as potential reasons for impaired male fertility (40). It has been proven that experimentally induced diabetes impairs sperm's fertilizing potential by adversely affecting DNA integrity, chromatin quality, and sperm parameters (17). According to another study that evaluated the impact of DM on reproductive functions, diabetic men (52%) had higher rates of sperm DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial DNA deletions than non-diabetic men (32%) (19).

The abnormal structure of sperm chromatin or DNA structure is hypothesized to stem from 4 potential causes: inadequate recombination throughout spermatogenesis, which generally causes cell abortion; extraordinary spermatid maturation (protamination disturbances); abortive apoptosis; and oxidative stress (41). ROS play an important physiological role by modulating gene and protein activities that are vital for sperm proliferation, differentiation, and function. In the semen of fertile men, the production of ROS is effectively regulated by the presence of seminal antioxidants. However, detrimental effects of ROS occur when their generation exceeds the antioxidant capabilities of the male reproductive system or the seminal plasma (42).

The processes that lead to DNA damage in ejaculated semen are correlated. It has been determined that during travel through the epididymis, defective spermatid protamination and the creation of disulfide bridges caused by insufficient thiol oxidation, lead to poor sperm chromatin packaging, increasing the sensitivity of sperm cells to DNA fragmentation induced by ROS (43).

Sperm chromatin damage is primarily influenced by both internal factors (such as genetic defects, apoptosis failure, and maturation defects) and external factors (like prolonged retention in the epididymis, varicocele, drug and alcohol use, smoking, obesity, environmental pollution, systemic infection, and diseases), all of which contribute to the production of ROS (44).

3.3. Diabetes and abnormal sperm chromatin structures

Previous studies have shown that the DNA integrity of spermatozoa is needed for normal fertilization and inheritance of paternal genes in offspring (35, 36). Moreover, the sperm plasma membrane has lipids as polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are sensitive to damage by ROS, resulting in lipid peroxidation (37, 38). Abnormal sperm chromatin packaging may lead to complications through various mechanisms. For instance, inadequate condensation and stabilization of the chromatin results in the DNA being more vulnerable (39). Conversely, excessive compaction of the sperm chromatin can delay the proper timing for the rapid transfer of the sperm DNA into the ooplasm. Therefore, it's critical to consider any factors that disrupt the normal compaction of sperm chromatin -either decrease or increase- as potential reasons for impaired male fertility (40). It has been proven that experimentally induced diabetes impairs sperm's fertilizing potential by adversely affecting DNA integrity, chromatin quality, and sperm parameters (17). According to another study that evaluated the impact of DM on reproductive functions, diabetic men (52%) had higher rates of sperm DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial DNA deletions than non-diabetic men (32%) (19).

The abnormal structure of sperm chromatin or DNA structure is hypothesized to stem from 4 potential causes: inadequate recombination throughout spermatogenesis, which generally causes cell abortion; extraordinary spermatid maturation (protamination disturbances); abortive apoptosis; and oxidative stress (41). ROS play an important physiological role by modulating gene and protein activities that are vital for sperm proliferation, differentiation, and function. In the semen of fertile men, the production of ROS is effectively regulated by the presence of seminal antioxidants. However, detrimental effects of ROS occur when their generation exceeds the antioxidant capabilities of the male reproductive system or the seminal plasma (42).

The processes that lead to DNA damage in ejaculated semen are correlated. It has been determined that during travel through the epididymis, defective spermatid protamination and the creation of disulfide bridges caused by insufficient thiol oxidation, lead to poor sperm chromatin packaging, increasing the sensitivity of sperm cells to DNA fragmentation induced by ROS (43).

Sperm chromatin damage is primarily influenced by both internal factors (such as genetic defects, apoptosis failure, and maturation defects) and external factors (like prolonged retention in the epididymis, varicocele, drug and alcohol use, smoking, obesity, environmental pollution, systemic infection, and diseases), all of which contribute to the production of ROS (44).

3.3. Diabetes and abnormal sperm chromatin structures

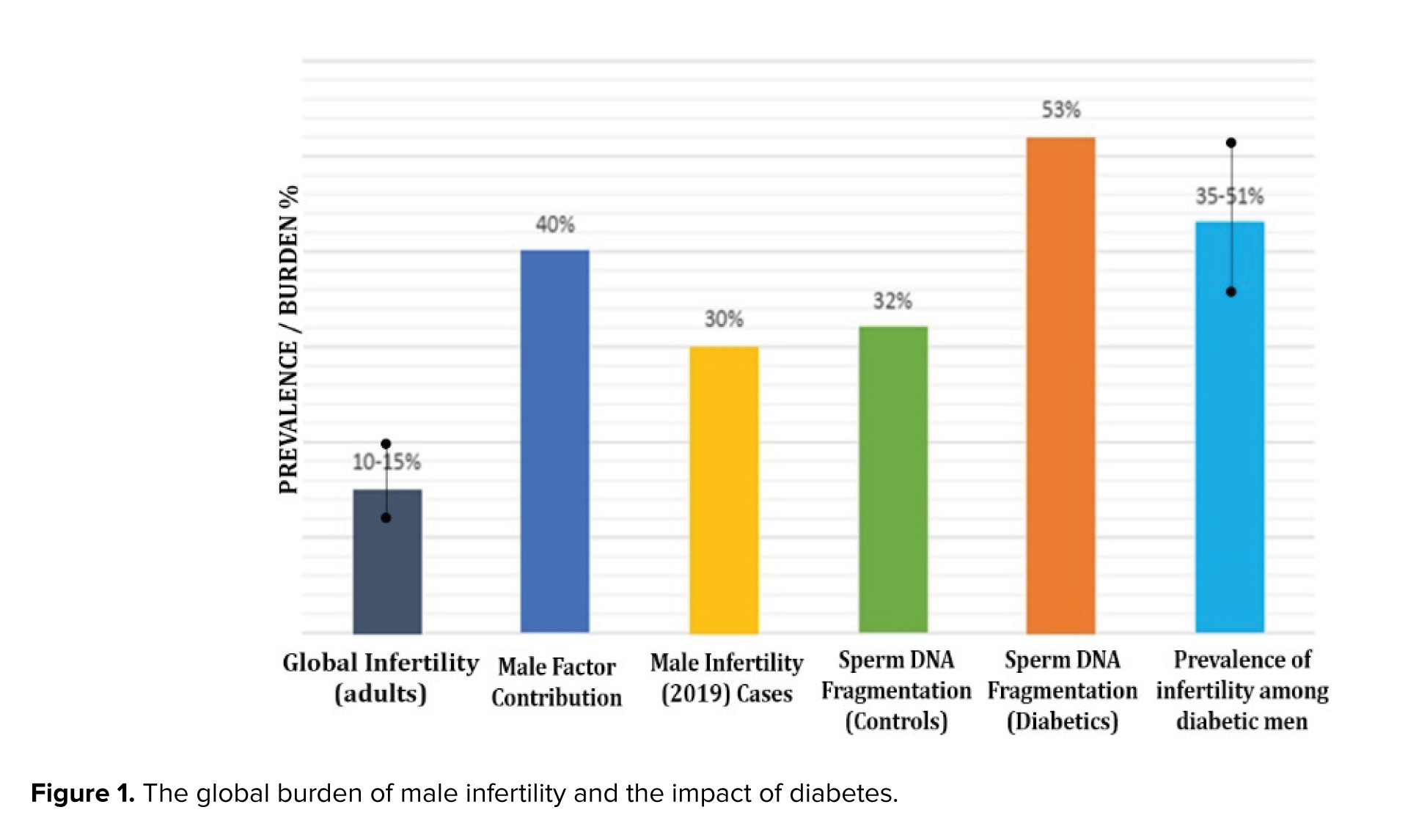

Diabetic men with normal semen parameters demonstrated significantly higher levels of defects in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA of sperm. This may be attributed to abnormally high glucose levels and the related oxidative stress (19). In addition to hyperglycemia, numerous factors significantly contribute to the development of DM, including oxidative stress and hyperlipidemia. Increased levels of advanced glycation end products, which are a consequence of oxidative damage, have been found in the seminal plasma, reproductive system, and sperm of diabetic men, implying their role in the damage to sperm DNA caused by ROS (45-47). It has been shown that free radicals play a vital role in the beginning and the advancement of late-stage diabetic complications, as they have the potential to harm proteins, lipids, and DNA (48). In an oxidative environment, cells may undergo apoptosis or necrosis, which is a primary mechanism that results in DNA fragmentation in sperm. Apoptosis and necrosis are probably initiated by impaired chromatin maturation in the testis during passes through the male genital tract and occur during spermatogenesis, post-spermiation, or both. Figure 2 shows a visual summary of how diabetes affects sperm and causes male infertility. These adverse effects have prompted the development of novel therapeutic approaches aimed at mitigating sperm DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress in men facing infertility issues (49).

According to the report by Mangoli and colleagues diabetes did not show any harmful effects on histone-protamine replacement during the testicular phase of sperm chromatin packaging (17). Additionally, another study revealed that despite the absence of a significant difference in mRNA levels of protamines between the diabetic and nondiabetic individuals, the results demonstrated a positive relationship between the mRNA levels of P1 and the progressive motility of sperm (50).

3.4. Diabetes and inheritance of epigenetic modification

According to the report by Mangoli and colleagues diabetes did not show any harmful effects on histone-protamine replacement during the testicular phase of sperm chromatin packaging (17). Additionally, another study revealed that despite the absence of a significant difference in mRNA levels of protamines between the diabetic and nondiabetic individuals, the results demonstrated a positive relationship between the mRNA levels of P1 and the progressive motility of sperm (50).

3.4. Diabetes and inheritance of epigenetic modification

The epigenetic pattern begins in the reproductive cells and is crucial for normal embryonic and postnatal development (51). It is posited that epigenetic modifications occurring during the development of germ cells significantly influence gene expression, meiosis, genomic stability, and genomic imprinting (52). The term “epigenetics” describes a range of mechanisms that induce lasting and heritable alterations in gene activity, without changing genetic information stored in DNA (53).

Epigenetic modifications, which include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation, have a crucial role in the dynamics of gene expression and cellular function (21). These modifications are critically involved in regulating pathways associated with disease pathogenesis, suggesting their potential as therapeutic targets (54).

DNA methylation, a widespread epigenetic alteration, occurs particularly at cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites, where a methyl group is added to the 5th position of cytosine. DNA methylation performs an essential role in controlling gene activity via modulating DNA transcription (55) and contributes to genome protection through limiting transposable element activity within the germ line and potentially in somatic cells (56). The paternal contribution to the development of offspring is primarily through sperm, and researchers determined that sperm DNA methylation is critical in passing on epigenetic data from father to the next generation (57).

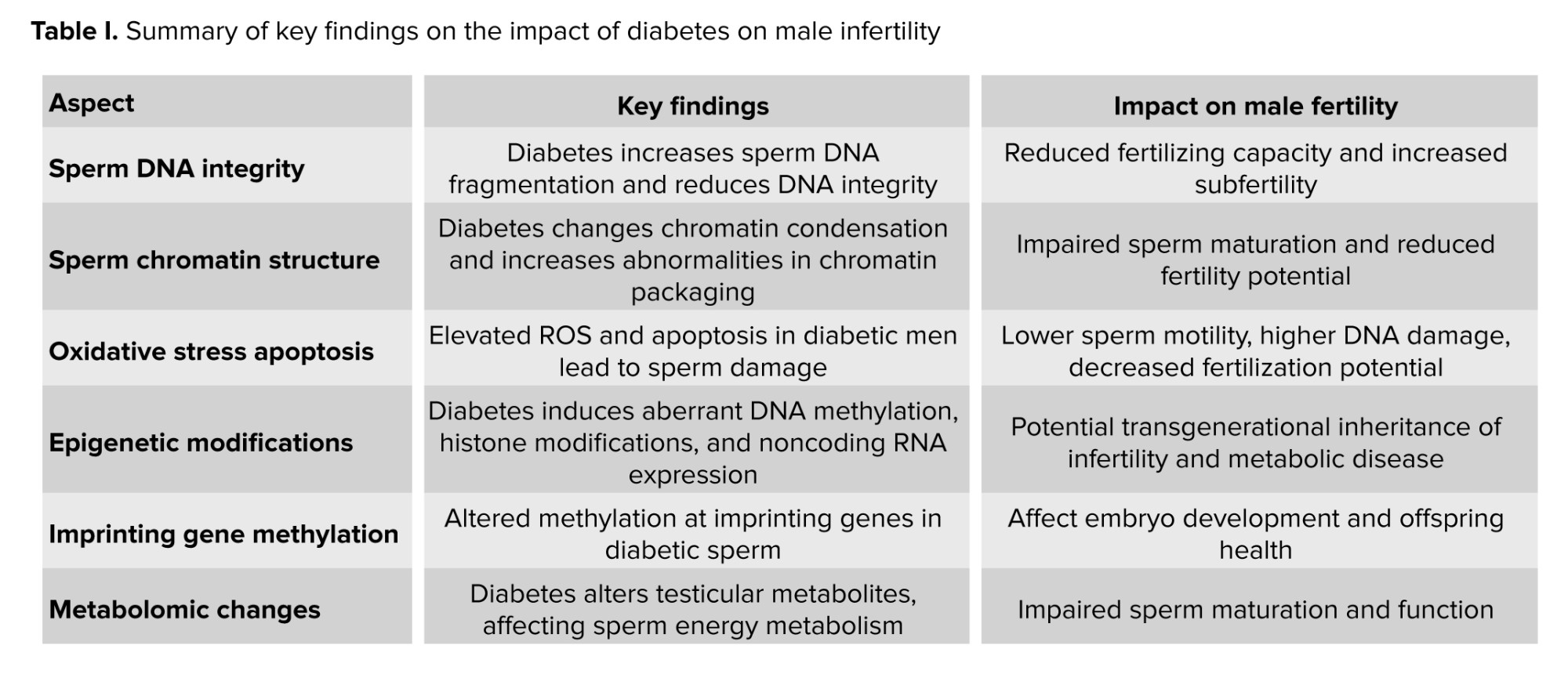

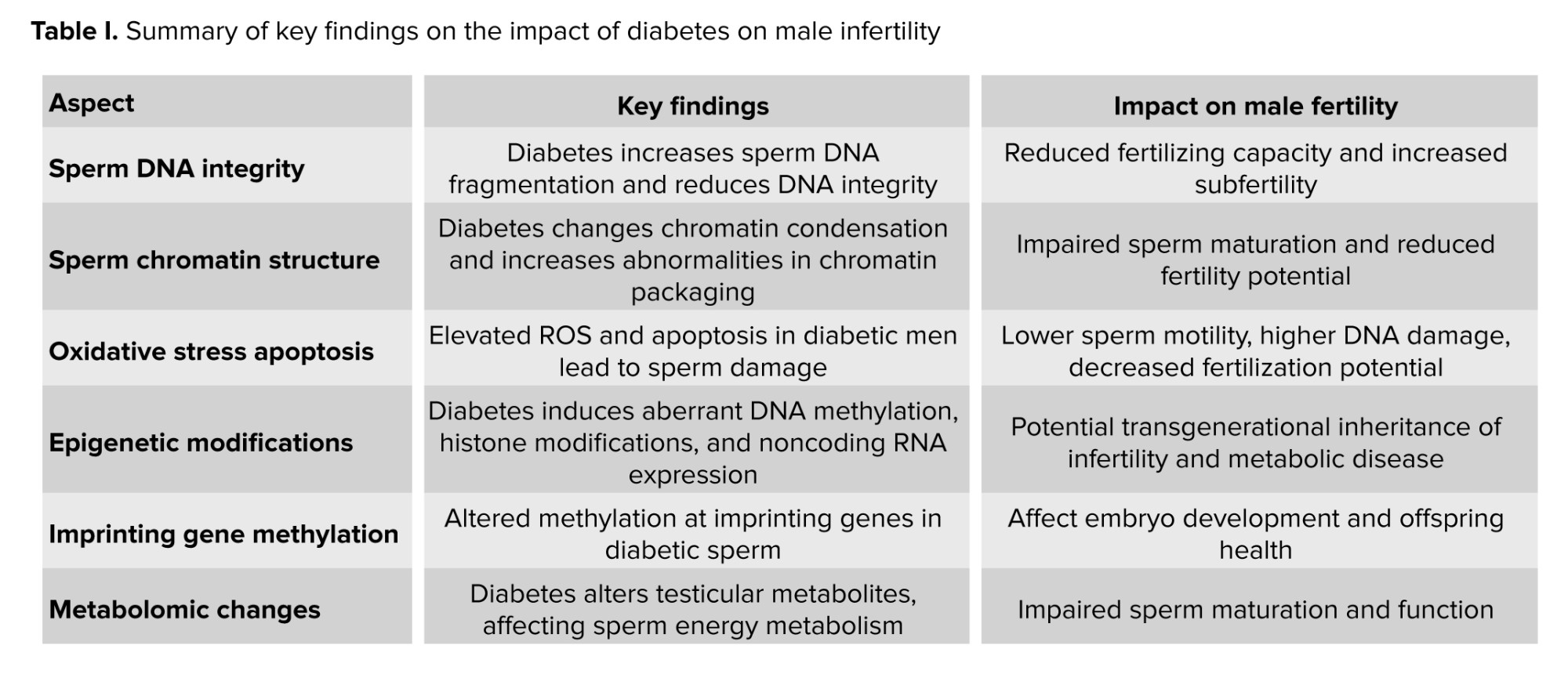

The effects of paternal diabetes on sperm epigenetics until now remain mostly undetermined. Recent investigations have revealed alterations in methylation patterns in the progeny of individuals diagnosed with paternal diabetes. Paternal prediabetes is a risk factor for intergenerational transmission of diabetes, influenced by the epigenetic modifications of gametes (58). Research using epigenetic profiling to analyze the pancreatic islets of offspring indicated significant variations in cytosine methylation associated with paternal prediabetes, particularly consistent methylation alterations in several insulin signaling genes (59). It has been determined that paternal prediabetes changed most methylome patterns in sperm. This research implies that prediabetes may be transmitted across generations in mammals through an epigenetic mechanism. The development of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in children could be a consequence of paternal diabetes, potentially mediated by a reduction in the expression of genes involved in insulin signaling pathways and glycometabolism. This outcome could be due to changes in the overall methylation levels of sperm resulting from paternal diabetes, consequently heightening the risk of diabetes in subsequent generations (60). Table I presents a summary of key findings on the impact of diabetes on male infertility.

3.5. The effect of diabetes treatment on chromatin structure and fertility

Epigenetic modifications, which include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation, have a crucial role in the dynamics of gene expression and cellular function (21). These modifications are critically involved in regulating pathways associated with disease pathogenesis, suggesting their potential as therapeutic targets (54).

DNA methylation, a widespread epigenetic alteration, occurs particularly at cytosine-phosphate-guanine sites, where a methyl group is added to the 5th position of cytosine. DNA methylation performs an essential role in controlling gene activity via modulating DNA transcription (55) and contributes to genome protection through limiting transposable element activity within the germ line and potentially in somatic cells (56). The paternal contribution to the development of offspring is primarily through sperm, and researchers determined that sperm DNA methylation is critical in passing on epigenetic data from father to the next generation (57).

The effects of paternal diabetes on sperm epigenetics until now remain mostly undetermined. Recent investigations have revealed alterations in methylation patterns in the progeny of individuals diagnosed with paternal diabetes. Paternal prediabetes is a risk factor for intergenerational transmission of diabetes, influenced by the epigenetic modifications of gametes (58). Research using epigenetic profiling to analyze the pancreatic islets of offspring indicated significant variations in cytosine methylation associated with paternal prediabetes, particularly consistent methylation alterations in several insulin signaling genes (59). It has been determined that paternal prediabetes changed most methylome patterns in sperm. This research implies that prediabetes may be transmitted across generations in mammals through an epigenetic mechanism. The development of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in children could be a consequence of paternal diabetes, potentially mediated by a reduction in the expression of genes involved in insulin signaling pathways and glycometabolism. This outcome could be due to changes in the overall methylation levels of sperm resulting from paternal diabetes, consequently heightening the risk of diabetes in subsequent generations (60). Table I presents a summary of key findings on the impact of diabetes on male infertility.

3.5. The effect of diabetes treatment on chromatin structure and fertility

a. Insulin and insulin-related therapy

Research in animal studies (diabetic rats) indicates that diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ), a compound toxic to pancreatic beta-cells, adversely affects the secretory products of the epididymis, potentially due to a reduced androgenic status. The altered composition of these secretory products leads to impaired sperm maturation, which may contribute to the observed decline in fertility among STZ-diabetic rats. The restoration of these alterations, whether partially or entirely, by insulin replacement implies that insulin plays a crucial role, alongside testosterone, in facilitating the processes necessary for sperm maturation. Human clinical trials have shown that elevated insulin levels in men are associated with an increased incidence of DNA damage and a reduced likelihood of successful in vitro fertilization (61, 62). Some interventions, such as metformin administration, dietary modifications, and regular physical activity, have been shown to effectively manage insulin levels. Treatment of hyperinsulinemia in men can delay the onset and progression of type 2 diabetes and possibly improve sperm parameters (2, 63-65).

b. Biguanides (Metformin)

Alves et al. in their in vitro study reported that metformin reduces mRNA and protein levels of glycolysis-related transporters in Sertoli cells while simultaneously enhancing their functional activity. Additionally, metformin stimulates the synthesis of alanine, which plays a crucial role in promoting antioxidant defenses and preserving the balance of NADH/NAD+. Higher levels of lactate in metformin-treated Sertoli cells supply essential nutrients and inhibit apoptosis of germ cell formations. Thus, metformin could be considered as an appropriate antidiabetic agent for male patients with type 2 diabetes in their reproductive years (66). Diabetic rat treatment with a combination of Metformin and Repaglinide significantly decreased the percentage of sperms with abnormal morphology and increased the rate of sperms with progressive motility (67).

c. Sulfonylureas (Gliclazide, Glibenclamide)

It has been reported that administering Gliclazide in diabetic rats improved testis structure, sperm morphology, and spermatogenesis process, and also increased sperm count (68). Glibenclamide is one of the drugs that control high blood sugar. In a study by Babaei et al. the effect of this drug on sperm parameters and DNA damage in diabetic rats induced by ST was investigated. The data showed that Glibenclamide significantly increased sperm parameters, including sperm count, sperm motility, viability, and sperm with normal morphology. It also improved DNA damage and the process of spermiogenesis (69).

d. Thiazolidinediones (Pioglitazone)

Pioglitazone is an anti-diabetic drug that is prescribed alone or in combination with Metformin or other drugs to control high blood sugar in diabetics. The effect of this drug on sperm parameters and inflammatory biomarkers, apoptosis, and oxidative stress in the testes of diabetic rats showed that sperm parameters improved significantly. In addition, tissue levels of malondialdehyde and nitric oxide decreased, and total antioxidant capacity in the testes increased (70).

Overall, can be said that control of blood sugar positively affects sperm parameters and, as a result, improves men’s fertility (20).

4. Limitations

Research in animal studies (diabetic rats) indicates that diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ), a compound toxic to pancreatic beta-cells, adversely affects the secretory products of the epididymis, potentially due to a reduced androgenic status. The altered composition of these secretory products leads to impaired sperm maturation, which may contribute to the observed decline in fertility among STZ-diabetic rats. The restoration of these alterations, whether partially or entirely, by insulin replacement implies that insulin plays a crucial role, alongside testosterone, in facilitating the processes necessary for sperm maturation. Human clinical trials have shown that elevated insulin levels in men are associated with an increased incidence of DNA damage and a reduced likelihood of successful in vitro fertilization (61, 62). Some interventions, such as metformin administration, dietary modifications, and regular physical activity, have been shown to effectively manage insulin levels. Treatment of hyperinsulinemia in men can delay the onset and progression of type 2 diabetes and possibly improve sperm parameters (2, 63-65).

b. Biguanides (Metformin)

Alves et al. in their in vitro study reported that metformin reduces mRNA and protein levels of glycolysis-related transporters in Sertoli cells while simultaneously enhancing their functional activity. Additionally, metformin stimulates the synthesis of alanine, which plays a crucial role in promoting antioxidant defenses and preserving the balance of NADH/NAD+. Higher levels of lactate in metformin-treated Sertoli cells supply essential nutrients and inhibit apoptosis of germ cell formations. Thus, metformin could be considered as an appropriate antidiabetic agent for male patients with type 2 diabetes in their reproductive years (66). Diabetic rat treatment with a combination of Metformin and Repaglinide significantly decreased the percentage of sperms with abnormal morphology and increased the rate of sperms with progressive motility (67).

c. Sulfonylureas (Gliclazide, Glibenclamide)

It has been reported that administering Gliclazide in diabetic rats improved testis structure, sperm morphology, and spermatogenesis process, and also increased sperm count (68). Glibenclamide is one of the drugs that control high blood sugar. In a study by Babaei et al. the effect of this drug on sperm parameters and DNA damage in diabetic rats induced by ST was investigated. The data showed that Glibenclamide significantly increased sperm parameters, including sperm count, sperm motility, viability, and sperm with normal morphology. It also improved DNA damage and the process of spermiogenesis (69).

d. Thiazolidinediones (Pioglitazone)

Pioglitazone is an anti-diabetic drug that is prescribed alone or in combination with Metformin or other drugs to control high blood sugar in diabetics. The effect of this drug on sperm parameters and inflammatory biomarkers, apoptosis, and oxidative stress in the testes of diabetic rats showed that sperm parameters improved significantly. In addition, tissue levels of malondialdehyde and nitric oxide decreased, and total antioxidant capacity in the testes increased (70).

Overall, can be said that control of blood sugar positively affects sperm parameters and, as a result, improves men’s fertility (20).

4. Limitations

The study of diabetes and its effects on male infertility, specifically focusing on sperm chromatin damage and epigenetic alterations, faces several significant limitations.

Primarily, a substantial portion of the current comprehension is largely based on animal models, such as STZ-induced diabetic rodents, which may not fully reflect the complexity of human diabetes and its impact on reproductive outcomes. This limits the direct translation of findings to clinical practice (71, 72). Furthermore, despite evidence indicating that diabetes induces oxidative stress, disrupts steroidogenesis, and impairs sperm motility and DNA integrity, the specific molecular mechanisms driving these effects remain incompletely comprehended. Specifically, the exact pathways through which hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency modulate epigenetic regulation during spermatogenesis require further research. Moreover, research focused on epigenetic modifications as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNA expression diabetic sperm is limited in number and often employs small sample sizes, which reduces statistical robustness and generalizability (73-75).

Additionally, while some evidence from animal research indicates the potential for intergenerational inheritance of diabetes-related epigenetic modifications, this has not yet been definitively confirmed in human studies. Finally, the variability in study designs, types of diabetes, duration of disease, and treatment strategies complicates comparisons across studies and the establishment of conclusive statements (76, 77).

5. Clinical applications and future research

Primarily, a substantial portion of the current comprehension is largely based on animal models, such as STZ-induced diabetic rodents, which may not fully reflect the complexity of human diabetes and its impact on reproductive outcomes. This limits the direct translation of findings to clinical practice (71, 72). Furthermore, despite evidence indicating that diabetes induces oxidative stress, disrupts steroidogenesis, and impairs sperm motility and DNA integrity, the specific molecular mechanisms driving these effects remain incompletely comprehended. Specifically, the exact pathways through which hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency modulate epigenetic regulation during spermatogenesis require further research. Moreover, research focused on epigenetic modifications as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNA expression diabetic sperm is limited in number and often employs small sample sizes, which reduces statistical robustness and generalizability (73-75).

Additionally, while some evidence from animal research indicates the potential for intergenerational inheritance of diabetes-related epigenetic modifications, this has not yet been definitively confirmed in human studies. Finally, the variability in study designs, types of diabetes, duration of disease, and treatment strategies complicates comparisons across studies and the establishment of conclusive statements (76, 77).

5. Clinical applications and future research

DM has emerged as a key contributor to male infertility, mainly due to its damaging effects on sperm chromatin and induction of epigenetic modifications. In a clinical setting, the evaluation of the quality sperm chromatin quality and DNA integrity offers a promising biomarker for diagnosing infertility among men who have diabetes. This can guide personalized therapeutic strategies designed to mitigate reproductive dysfunction. Insulin replacement therapy shows promise in preventing sperm motility defects and testicular dysfunction related to diabetes, highlighting a path for targeted treatments for metabolic and oxidative stress (78). Emerging evidence also indicates that epigenetic therapies may be a practical way to reverse or mitigate diabetes-induced epigenetic changes in spermatozoa. Such strategies provide opportunities not just for treating infertility but also for reducing heritable risks transmitted to offspring (79). Therefore, preconception care that focuses on optimization of paternal metabolic health and glycemic control becomes a crucial component of fertility management in diabetic males.

Future research should focus on large-scale, well-controlled studies in human populations that integrate clinical, molecular, and epigenetic data to provide a more thorough characterization of the impact of diabetes on male reproductive health.

Studies employing a longitudinal design that follow diabetic men and their offspring would be particularly valuable to clarify the extent and mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance across generations. The application of advanced high-throughput technologies, including genome-wide methylation and chromatin accessibility assays, is recommended to uncover novel epigenetic alterations linked to diabetes.

Moreover, mechanistic studies are necessary to determine how hyperglycemia and dysregulation of insulin signaling specifically impact the epigenetic machinery during spermatogenesis. Research exploring potential therapeutic strategies, such as antioxidants or epigenetic modulators, may present opportunities to mitigate sperm damage and enhance fertility outcomes in diabetic men.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach integrating endocrinology, reproductive biology, and epigenetics will be crucial to translate emerging knowledge into effective clinical strategies for managing male infertility in the context of diabetes.

6. Conclusion

Future research should focus on large-scale, well-controlled studies in human populations that integrate clinical, molecular, and epigenetic data to provide a more thorough characterization of the impact of diabetes on male reproductive health.

Studies employing a longitudinal design that follow diabetic men and their offspring would be particularly valuable to clarify the extent and mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance across generations. The application of advanced high-throughput technologies, including genome-wide methylation and chromatin accessibility assays, is recommended to uncover novel epigenetic alterations linked to diabetes.

Moreover, mechanistic studies are necessary to determine how hyperglycemia and dysregulation of insulin signaling specifically impact the epigenetic machinery during spermatogenesis. Research exploring potential therapeutic strategies, such as antioxidants or epigenetic modulators, may present opportunities to mitigate sperm damage and enhance fertility outcomes in diabetic men.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach integrating endocrinology, reproductive biology, and epigenetics will be crucial to translate emerging knowledge into effective clinical strategies for managing male infertility in the context of diabetes.

6. Conclusion

This review examines the complex relationship between DM, sperm chromatin structure, and male fertility. Evidence suggests that diabetes can negatively impact sperm chromatin integrity, potentially leading to increased DNA fragmentation and other abnormalities. Oxidative stress caused by hyperglycemia appears to be a key culprit in this process.

Despite the clear association between diabetes and abnormal sperm chromatin structure, the impact of diabetes treatment on chromatin integrity remains less clear. While some studies show improved sperm parameters with treatment, further research is needed to determine the specific effects on chromatin structure and fertility outcomes. An intriguing emerging area of research explores the potential for diabetes to influence offspring health through epigenetic modifications in sperm DNA. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to novel therapeutic strategies in the future.

In conclusion, diabetes poses a significant threat to male fertility by disrupting sperm chromatin structure. While proper diabetes management and specific medications have shown promise in mitigating these effects, further research is crucial to fully elucidate the complex interplay between diabetes, sperm health, and male infertility.

Acknowledgments

This study was not financially supported. The authors acknowledge the use of artificial intelligence (Perplexity 5.0.AI) tools for spell-checking and grammar correction during the preparation of this manuscript. However, all content, analysis, and conclusions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Despite the clear association between diabetes and abnormal sperm chromatin structure, the impact of diabetes treatment on chromatin integrity remains less clear. While some studies show improved sperm parameters with treatment, further research is needed to determine the specific effects on chromatin structure and fertility outcomes. An intriguing emerging area of research explores the potential for diabetes to influence offspring health through epigenetic modifications in sperm DNA. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to novel therapeutic strategies in the future.

In conclusion, diabetes poses a significant threat to male fertility by disrupting sperm chromatin structure. While proper diabetes management and specific medications have shown promise in mitigating these effects, further research is crucial to fully elucidate the complex interplay between diabetes, sperm health, and male infertility.

Acknowledgments

This study was not financially supported. The authors acknowledge the use of artificial intelligence (Perplexity 5.0.AI) tools for spell-checking and grammar correction during the preparation of this manuscript. However, all content, analysis, and conclusions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Fertility & Infertility

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |