Fri, Jan 30, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 10 (October 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(10): 803-814 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.071

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Majidipour N, Sabbagh S, Nazarian H, Pourmotahari F, Azizolahi B. Evaluation of acute and chronic phases of COVID-19 on semen parameters and gonad hormones: A case-control study. IJRM 2025; 23 (10) :803-814

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3609-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3609-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran.

2- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran.

3- Men’s Health and Reproductive Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran.

5- Department of Laboratory Sciences, School of Paramedicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran. & Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Center, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran. ,behnam.azizolahi@yahoo.com; azizolahi.b@dums.ac.ir

2- Department of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran.

3- Men’s Health and Reproductive Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, School of Medicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran.

5- Department of Laboratory Sciences, School of Paramedicine, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran. & Infectious and Tropical Diseases Research Center, Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 414 kb]

(397 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (371 Views)

Full-Text: (4 Views)

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began with an initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread worldwide (1). Data reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates the vast scale of the pandemic: by April 12, 2023, a total of 762,791,152 COVID-19 infections and 6,897,025 related deaths had been officially confirmed across the globe (2).

COVID-19 predominantly affects the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous systems (3), but its impact extends to the immune system, often leading to excessive inflammation and a cytokine storm (4). 5 variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are classified as variants of concern by the WHO, including alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and Omicron (5). In November 2021, WHO identified the “Omicron” variant, and by January 6, 2022, this variant was confirmed in 149 countries, leading to a significant global increase in cases (6).

The virus targets cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (7), which is found not only in the respiratory system but also in the reproductive system. This discovery raised concerns about the potential impact of the virus on male fertility, with evidence suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 could affect semen quality and male reproductive function (8).

Men infected with COVID-19 have shown reduced sperm quality, potentially corresponding to either viral load or severity of the disease. However, some studies indicate that pre-existing fertility issues may contribute to this impairment (9). Men have also been reported to be more vulnerable to develop severe/fatal COVID-19 and impaired fertility than women, but the underlying reasons for this phenomenon remain unknown, warranting further investigations (10, 11). A study indicates that COVID-19 may cause orchitis, leading to oxidative stress, disrupted sperm production, and germ cell death, which ultimately reduces sperm quality (12). Furthermore, oxidative stress (OS) damages testicular function at macroscopic and microscopic levels. This manifests as lipid peroxidation on sperm membranes and sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation (SDF) within the spermatozoa (13). A recent study has shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection negatively affects semen parameters, including SDF and OS markers, even several months after diagnosis (14). Similarly, another study revealed that sperm concentration and motility were significantly reduced in men recovered from mild COVID-19 infection compared to a healthy control group (15). Research underscores that SARS-CoV-2 can disturb both somatic and germ cells within testes, highlighting the critical need for additional studies to fully comprehend the short- and long-term ramifications of the virus on male fertility (16).

The present study aimed to investigate the acute and long-term effects of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 virus on several aspects of male reproductive function by analyzing semen parameters, OS markers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT), as well as direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 in semen using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Additionally, blood levels of gonadotropin hormones, such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and testosterone, as well as SDF, were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This matched case-control study was carried out on 70 men at Ganjavian hospital in Dezful, Iran, to compare semen parameters, gonadotropin hormone levels, OS markers, and SDF between men with confirmed COVID-19 (cases) and healthy controls. Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method from adult men. The participants were then divided into 2 groups: the COVID+ group (cases, n = 35) and the COVID- group (controls, n = 35). Data collection and follow-up were conducted between July 2022 and January 2023.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The COVID+ group included married men aged 25-55 yr with at least one child, all of whom tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR. The COVID- group comprised age-matched healthy male participants with negative RT-PCR results for COVID-19 and no clinical symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, and dyspnea) at the time of enrollment. To address potential confounding variables such as age, matching was applied between COVID+ and COVID- groups (1:1 ratio).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: incomplete follow-up (i.e., failure to complete scheduled clinical or laboratory assessments), sexually transmitted infections (human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B/C, syphilis, or genital herpes diagnosed via serological testing or PCR), testicular abnormalities (palpable varicocele grade I-III), testicular atrophy (volume < 12 mL), history of prior testicular surgery (e.g., orchidopexy, varicocelectomy, or inguinal hernia repair documented by medical records), scrotal trauma (history of scrotal injury within the past year), acute inflammation (acute epididymitis and orchitis), history of childhood mumps (self-reported or medically documented mumps-associated orchitis), malignancies (present or past diagnosis of testicular cancer, leukemia, or lymphoma), using medications for reproductive system abnormalities (androgen supplements such as testosterone, anabolic steroids, or chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide within the past 6 months), substance use (current smoking > 5 cigarettes/day or alcohol consumption > 14 units/wk), endocrine disorders (diabetes mellitus: fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%; thyroid dysfunction: thyroid-stimulating hormone < 0.4 or > 4.0 mIU/L along with abnormal free thyroxine levels), and antibiotic use within the past 3 months for bacterial prostatitis, urinary tract infections, or respiratory infections.

2.3. Data sources/collection

2.3.1. Checklist

A structured checklist titled “Participant Information Checklist” was developed to gather demographic data and medical/surgical history of the participants. Individuals with a self-reported history of any medical condition or prior surgery were excluded from the study.

2.3.2. Semen sampling

Semen samples were collected from each participant during the acute phase (from the time of a positive RT-PCR result to 2 wk post-diagnosis) and the chronic phase (75 days post-diagnosis).

2.3.3. Semen analysis protocol

After 3 to 5 days of sexual abstinence, semen samples were collected by masturbation into sterile falcon tubes. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 30-60 min in a CO₂ incubator (set to 5% CO₂ and 95% relative humidity) to allow for liquefaction. After semen liquefaction, key sperm parameters (pH, volume, sperm count, motility percentage, and motion characteristics) were manually assessed by 2 expert observers and evaluated based on established WHO recommendations (17). Briefly, pH was measured using a pH paper and compared with a calibration strip. Sperm count was determined under a microscope using a hemocytometer after dilution (1:20, one part of semen mixed with 19 parts of a diluent, sodium bicarbonate solution). Then 10 µL of the diluted sample was loaded into a hemocytometer (a specialized chamber with a grid pattern that facilitates counting), and spermatozoa in several squares of the grid were counted. Finally, sperm count was calculated by multiplying the dilution factor by the volume of the chamber. Sperm counts ≥ 15 × 106/mL were considered normal. To assess sperm morphology, the semen samples were centrifuged, and the resulting pellets were used to prepare smears, which were then stained using both Papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin techniques. The stained slides were then examined under a light microscope at ×100 magnification. Sperm morphology was assessed by calculating the percentage of sperms with normal vs. abnormal shapes. A normal result was considered when morphologically intact sperms were ≥ 30%. Finally, sperm motility was categorized and assessed as follows: rapidly progressive (type A), slowly progressive (type B), non-progressive (type C), or immotile (type D). Based on WHO recommendations, normal fertility corresponds to ≥ 50% motility for A- and B-type sperms.

2.3.4. SARS-CoV-2 detection in semen

For SARS-CoV-2 detection, a separate aliquot of the semen sample was used. Total RNA was extracted from 140 µL of this aliquot with the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The extracted RNA was eluted in 30 µL of elution buffer. SARS-CoV-2 detection was then performed using the Pishtaz Teb Zaman Molecular COVID-19 RT-PCR kit (Iran), which targets the ORF1ab gene, the nucleoprotein (N) gene, and the RNase P gene as an internal control.

2.3.5. Hormone testing

Venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from each participant. Hormone levels, including FSH, LH, and testosterone, were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Pishtaz Teb Zaman, Iran).

2.3.6. OS evaluation

OS markers, including SOD, MDA, and CAT, were assessed in semen samples using diagnostic kits (ZellBio, Germany). These tests were performed on the liquid portion of semen samples after centrifugation and separation from sperms.

2.3.7. SDF assessment

The quality of SDF was assessed using the sperm chromatin dispersion method using a specialized kit manufactured by Shams Azma CO., Iran. The test involved preparing a smear slide from diluted semen samples, incubating the slide with appropriate buffers provided by the kit, dehydrating the slide with alcohol, and examining it under a light microscope. The percentage of SDF was determined by counting 500 sperms at x100 magnification.

2.4. Bias assessment

The risk of potential bias was addressed in the present study as follows:

2.4.1. Selection bias

This study used the convenience sampling method. This method could have led to a biased sample that might not be fully representative of the broader population of men affected by COVID-19. Specifically, the sample might not account for individuals who were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms and, therefore, did not seek medical attention.

2.4.2. Information bias

This study relied on self-reported data for inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thus, there could be a risk that some participants failed to accurately recall or report this information, leading to potential misclassification of participants.

2.4.3. Potential impact of the COVID-19 variant

This study focused on the Omicron variant; however, other variants might also affect men’s reproductive health. Therefore, the results of this study may not be fully generalizable to other variants of SARS-CoV-2 regarding Omicron variant’s distinct characteristics compared to other strains.

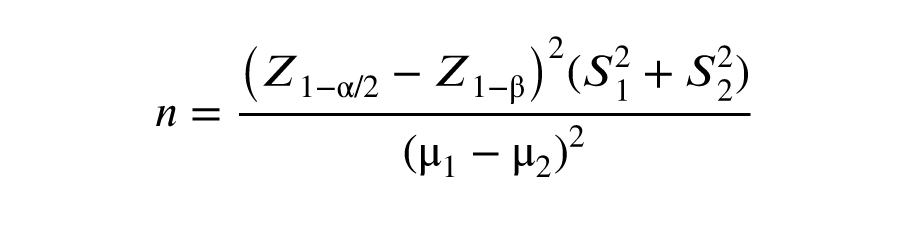

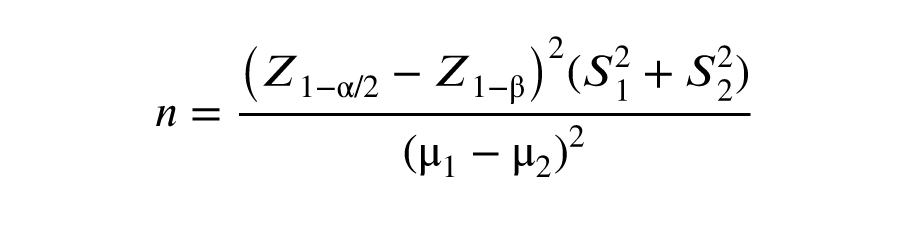

2.5. Sample size

The sample size was calculated considering a type I error (α) of 0.05, a power of 0.9 (1-β), and the 2 variables of sperm count and volume as the target outcomes in the study’s objectives. In this design, the maximum sample size was calculated as n = 34 per group. The dropout rate was estimated at 20%.

The symbols S1 and S2 denote the standard deviations, while µ1 and µ2 represent the means for group 1 and group 2, respectively.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Vice-Chancellor in Research Affairs, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.071). Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to present continuous variables, and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. To compare categorical variables between the COVID+ and COVID- groups, the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were employed, and continuous variables were compared between the groups using the Mann-Whitney U test based on the results of normality assessment according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. Semen parameters and laboratory variables at the first and second sampling phases were compared by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). 2-sided p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ characteristics

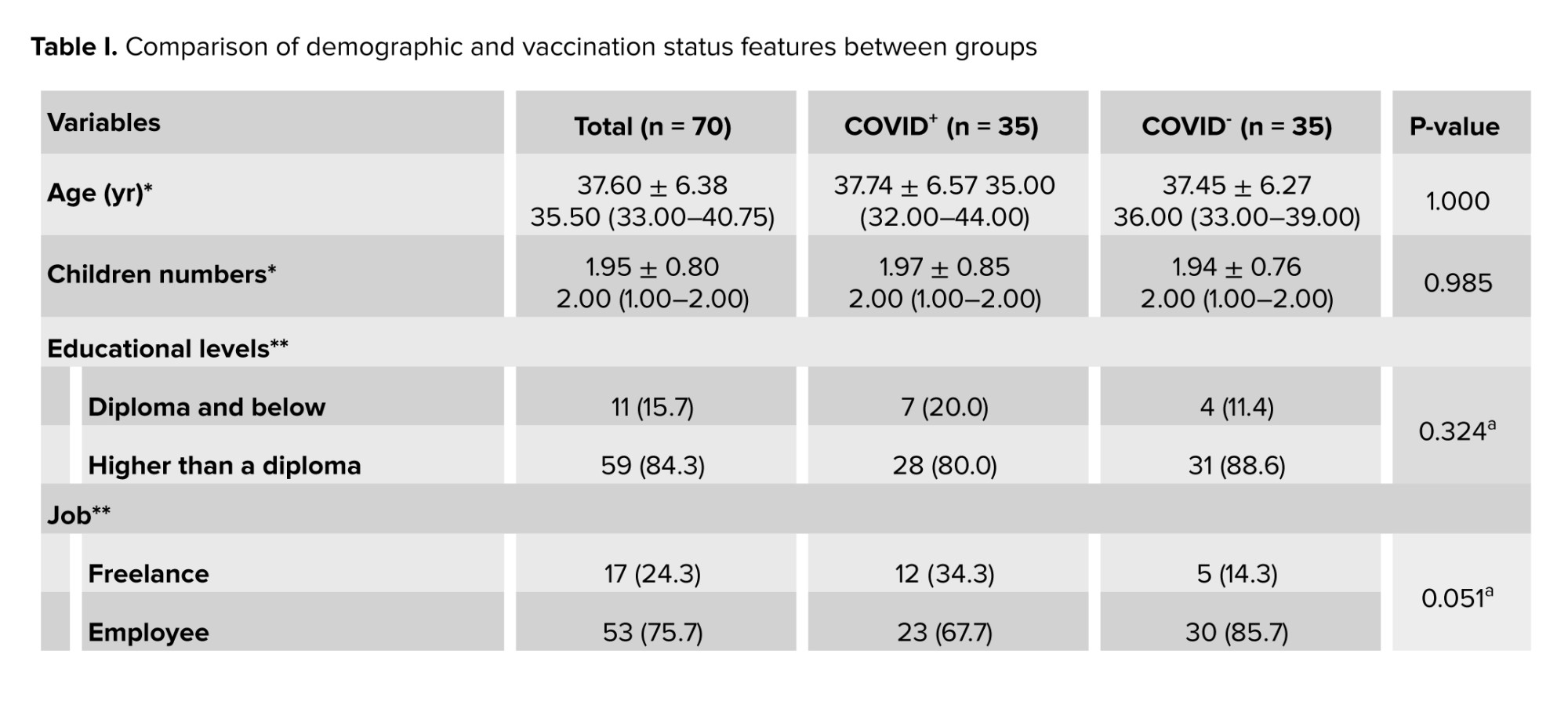

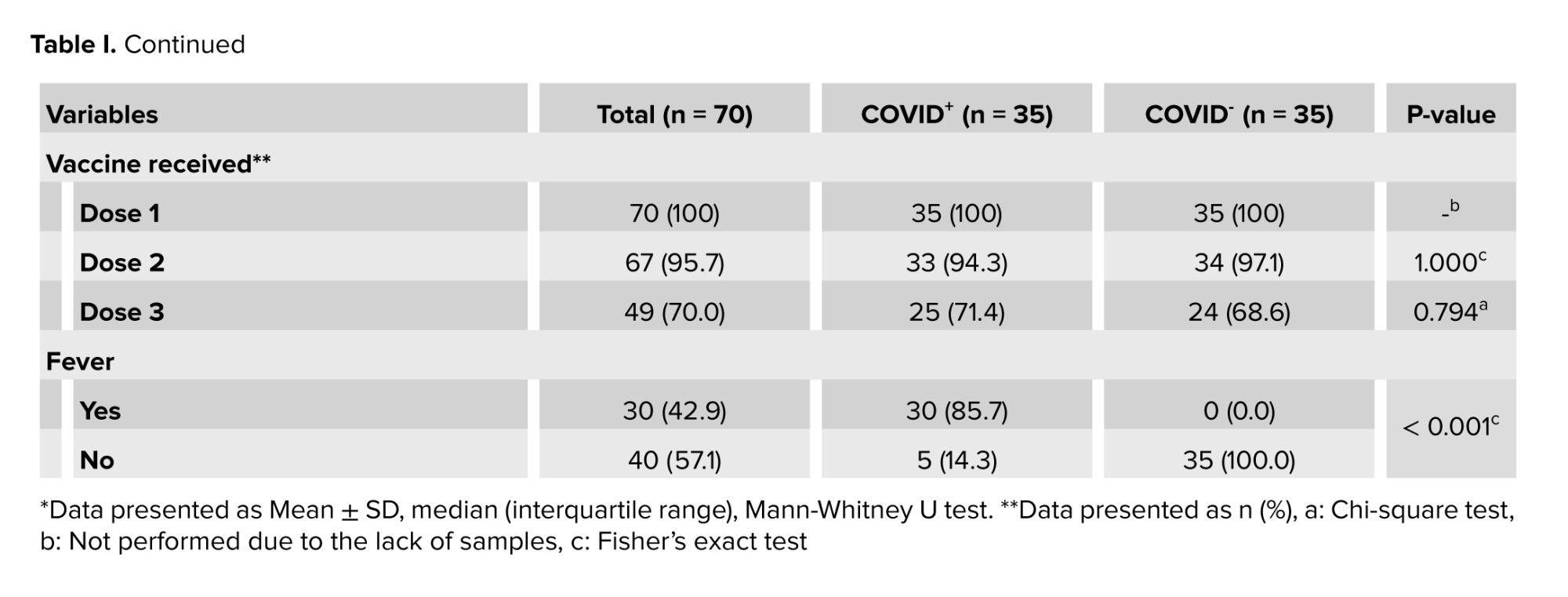

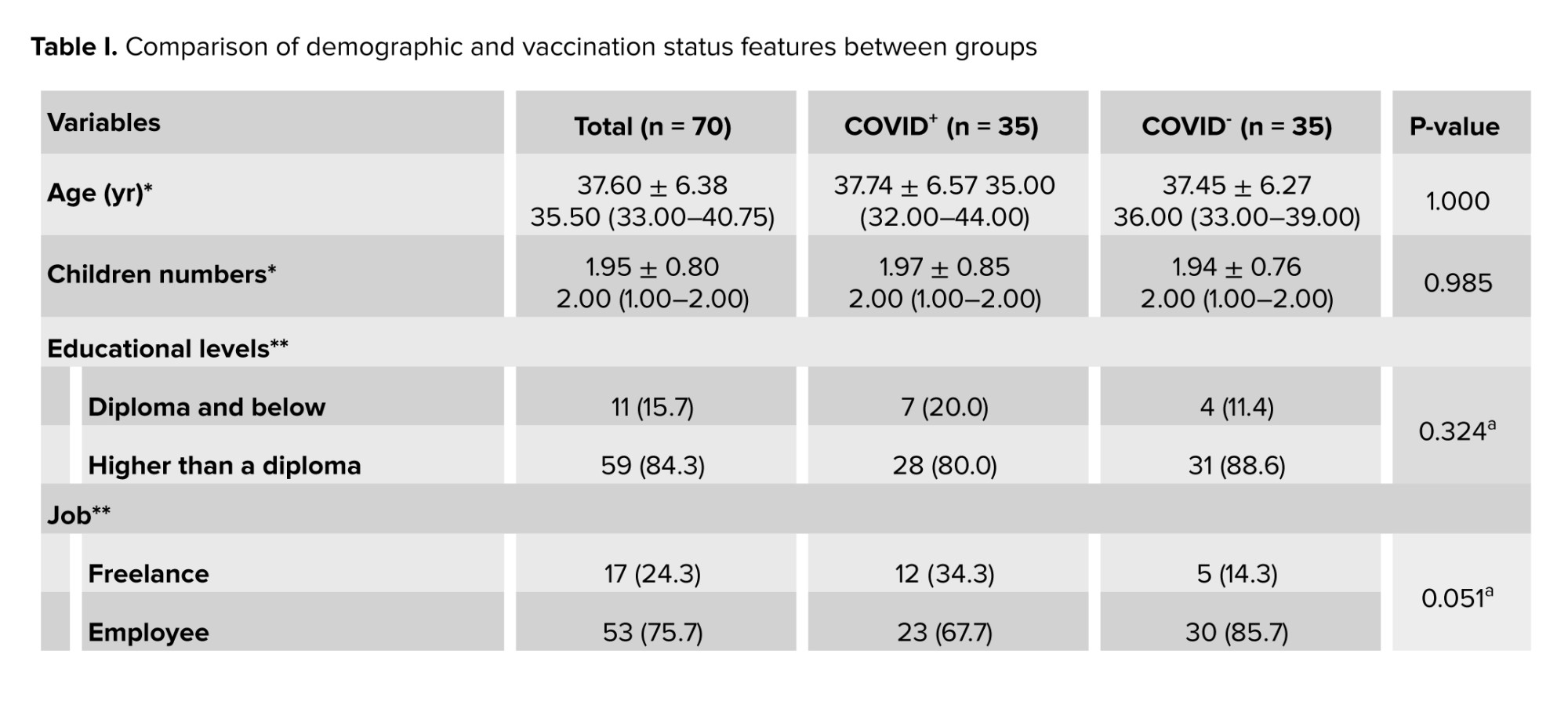

A total of 70 men with a mean age of 37.60 ± 6.38 yr were enrolled in this study. Demographic features and vaccination status in the COVID+ and COVID- groups have been shown in table I.

Participants in the 2 groups had no significant differences in terms of age, educational levels, job status, number of children, and vaccination history. All non-hospitalized participants reported at least one COVID-19 symptom during the acute phase of the infection. None of the individuals enrolled in the current study had sexually transmitted or other diseases such as AIDS, varicocele, etc.

The brands of COVID-19 vaccines received by the participants for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd doses were as follows:

Dose 1: Sinopharm (72.9%), Sputnik V (15.7%), AstraZeneca (8.6%), and Bharat Biotech (2.8%).

Dose 2: no vaccination (4.3%), Sinopharm (62.9%), Sputnik V (8.6%), AstraZeneca (5.7%), Barekat (5.7%), and Bharat Biotech (2.8%).

Dose 3: no vaccination (27.1%), Sputnik V (14.3%), Sinopharm (25.7%), and PastoCovac (32.9%).

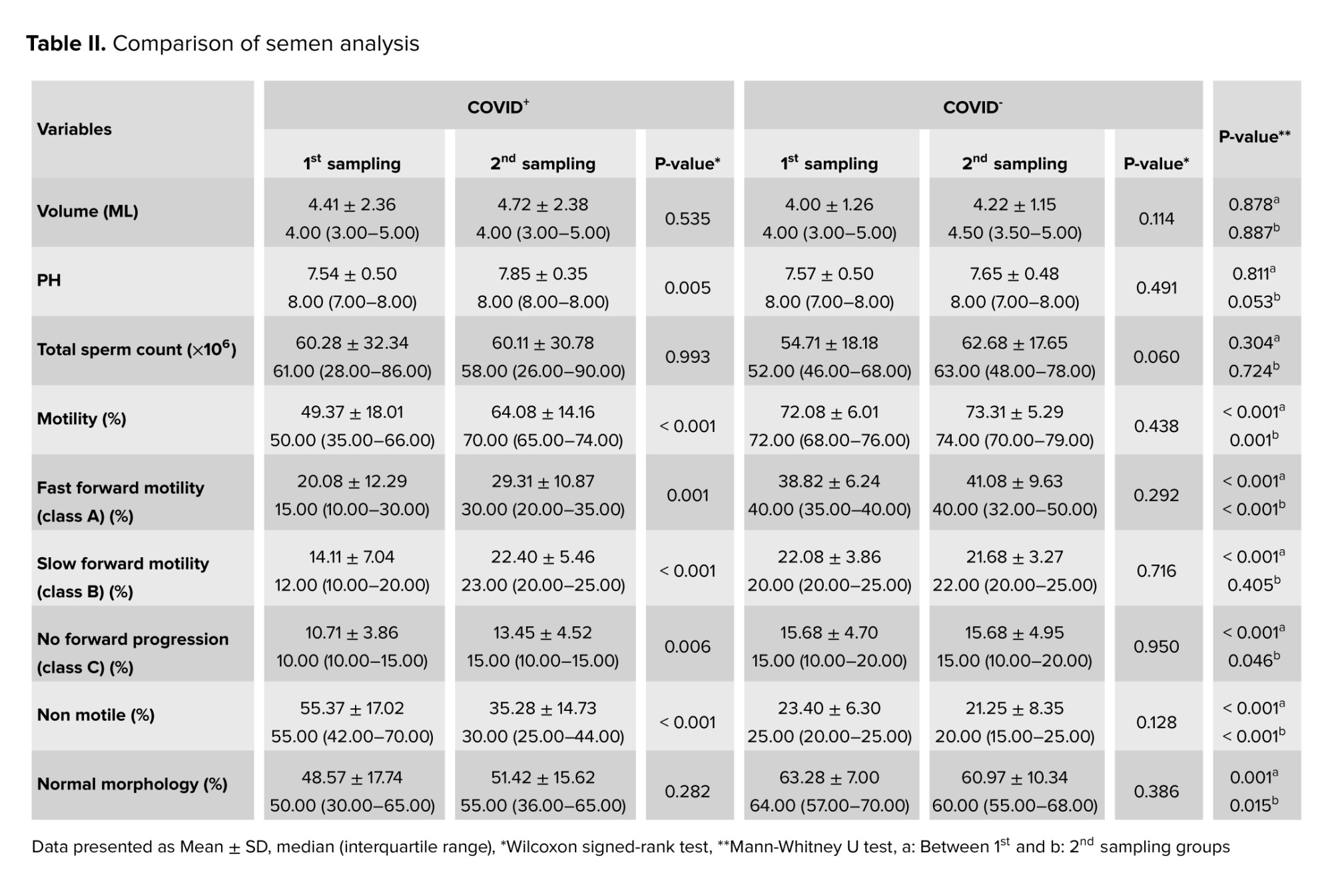

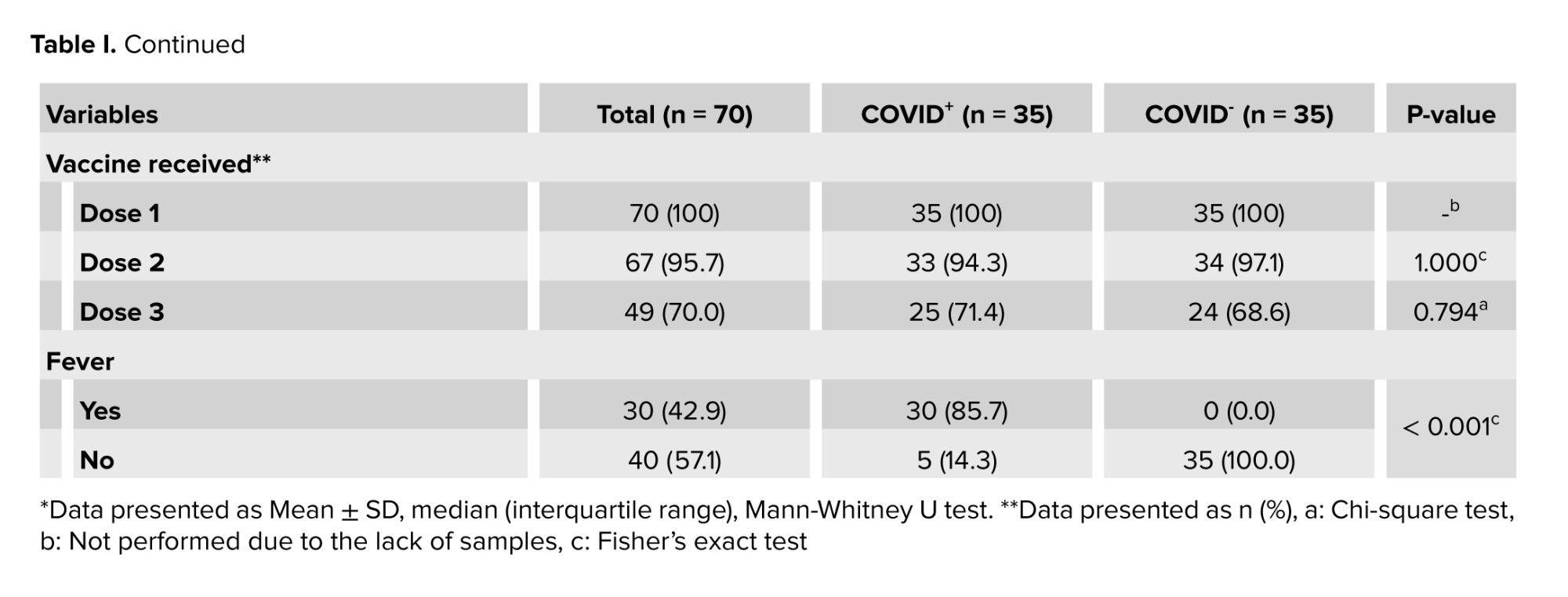

According to the results, significant within-group differences were observed in the COVID+ group between the 1st (i.e., acute phase) and 2nd (i.e., chronic phase) sampling periods regarding semen pH and sperm motility categories (i.e., fast forward motility; class A, slow forward motility; class B, no forward progression; class C, and non-motile) as shown in table II.

The findings of semen analysis showed that significant differences were observed between the COVID+ and COVID- groups both in the first and second sampling periods in terms of sperm parameters: motility, fast forward motility (class A), slow forward motility (class B, only in the first phase), no forward progression (class C), non-motile, as well as morphology. Total motility was significantly reduced during the acute phase of the infection (49.37 ± 18.01%) when compared to the chronic phase (64.08 ± 14.16%), indicating that sperm motility could be adversely affected during the early stages of the infection, with recovery occurring thereafter. Statistically significant differences were also observed in sperm morphology between the COVID+ and COVID- groups during the acute (p = 0.001) and chronic (p = 0.015) phases.

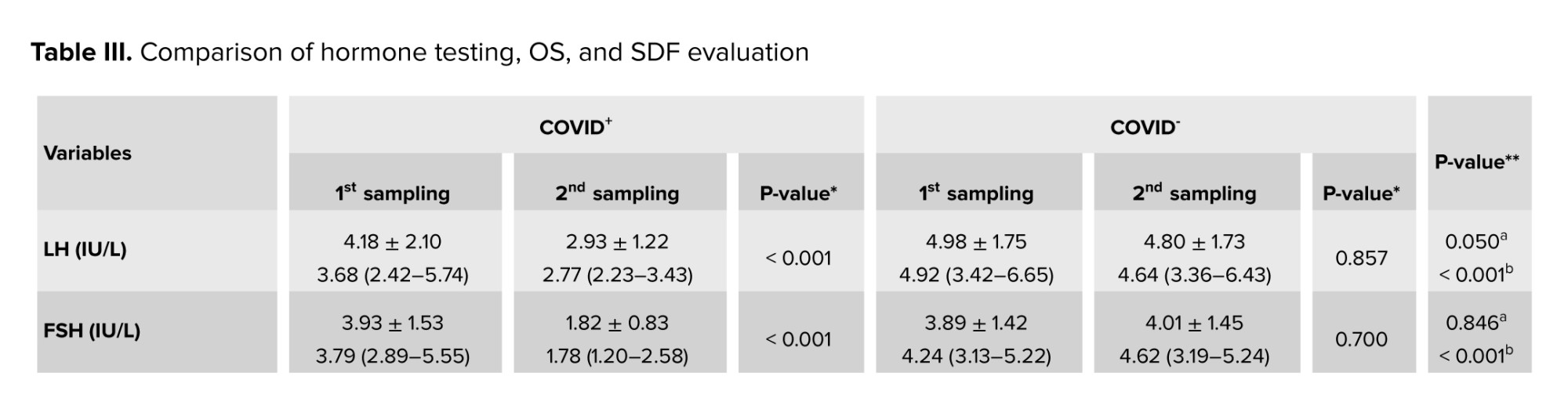

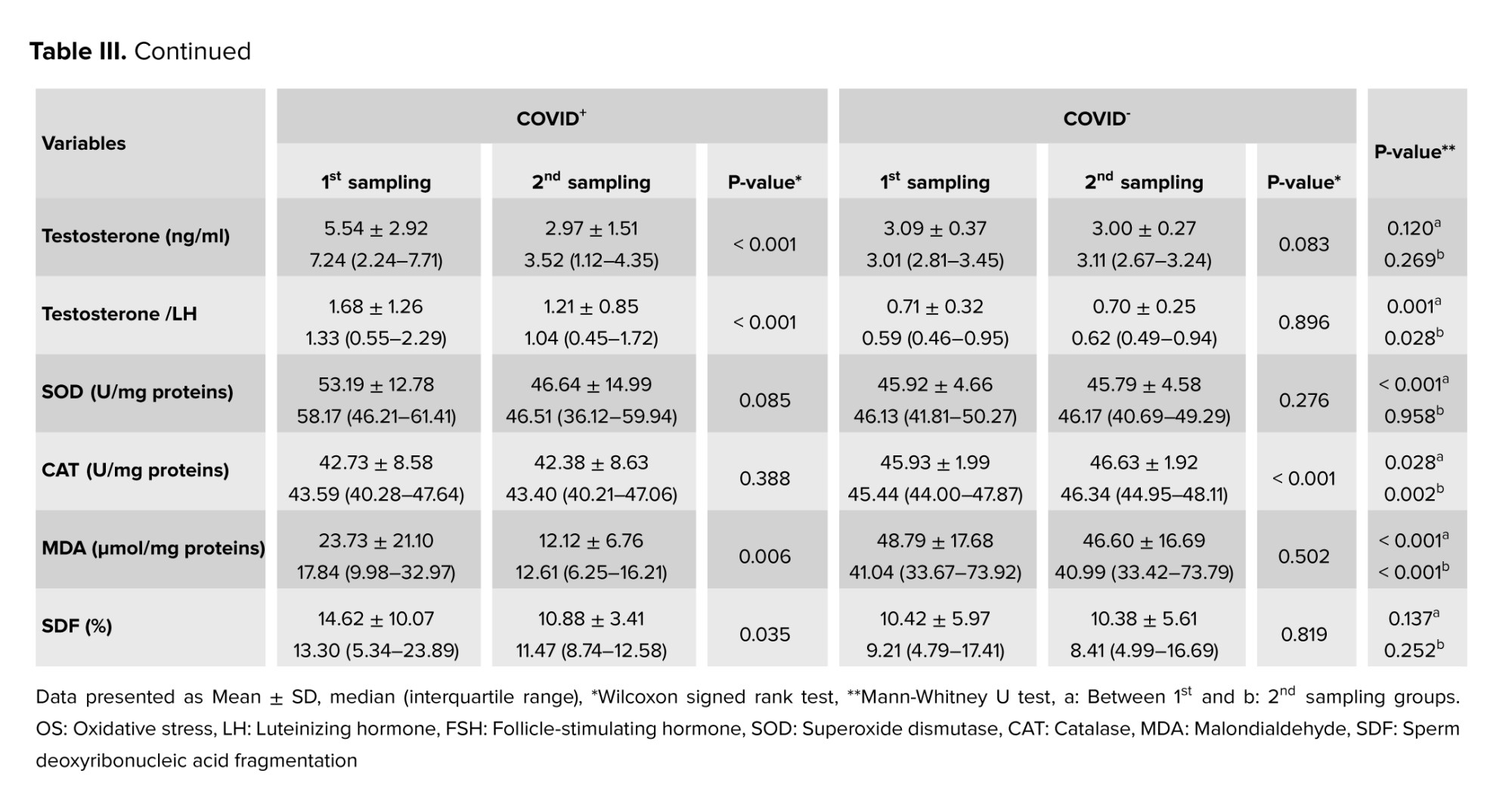

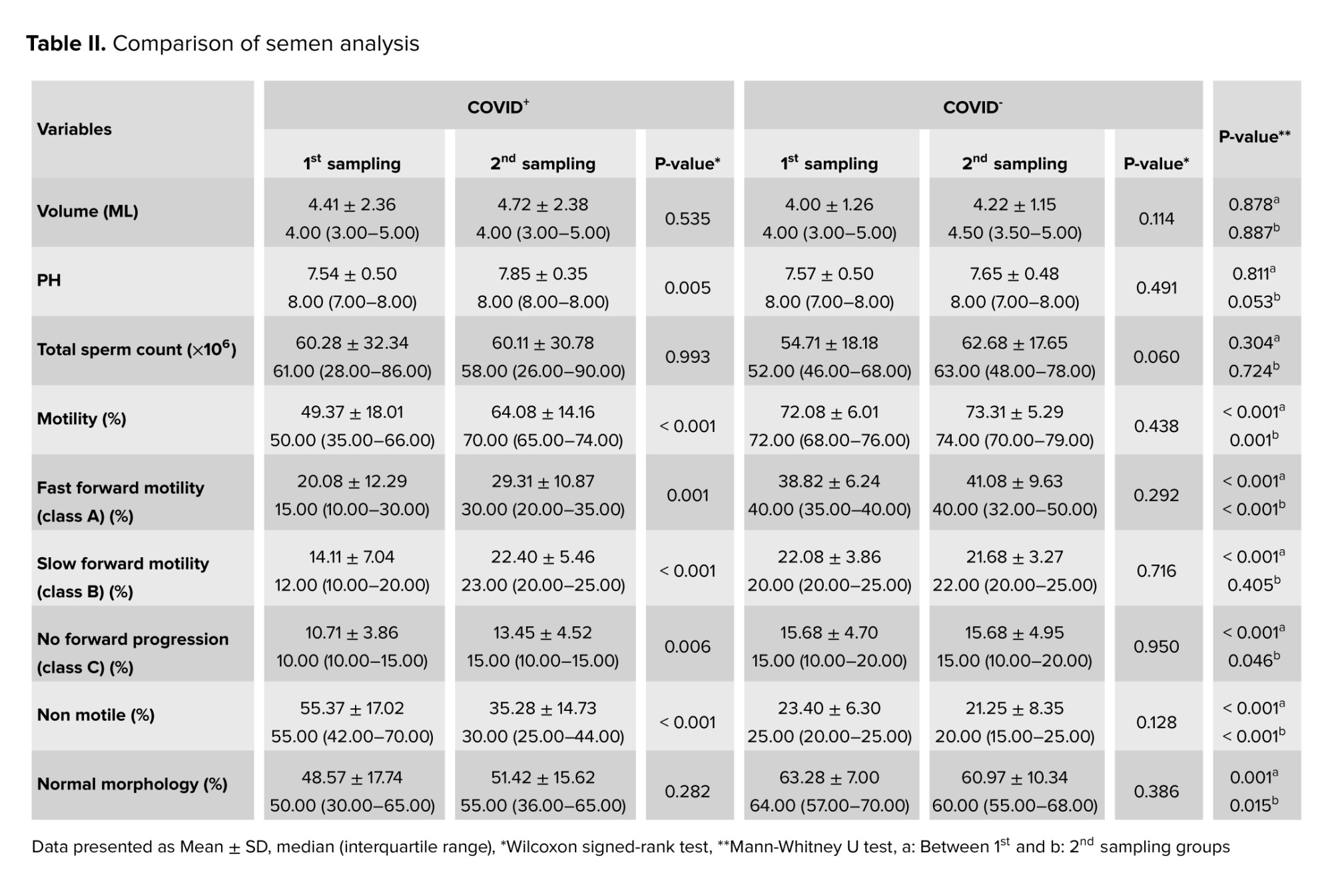

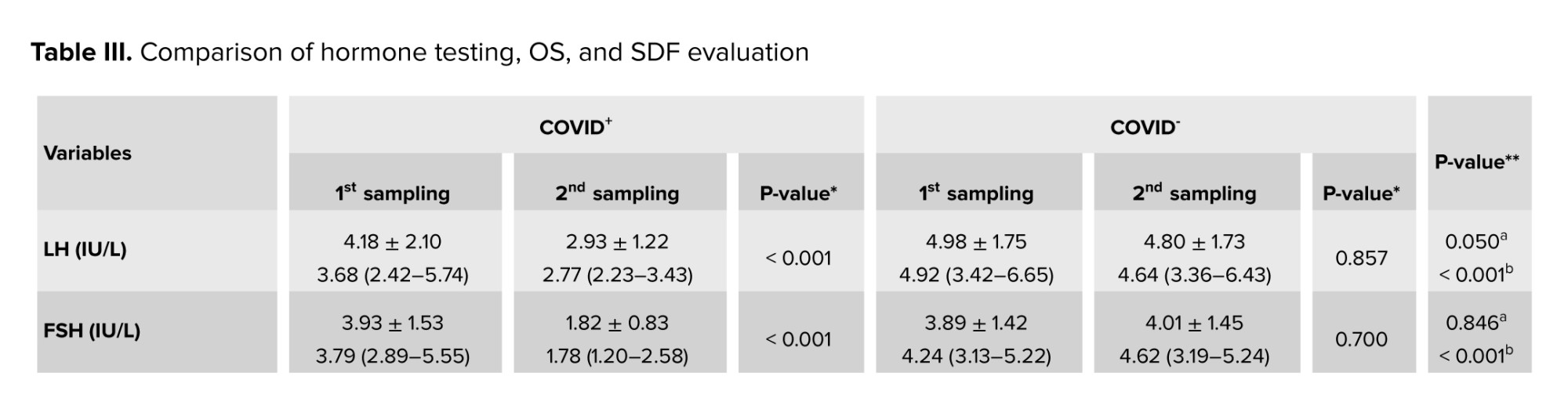

3.2. Hormone testing

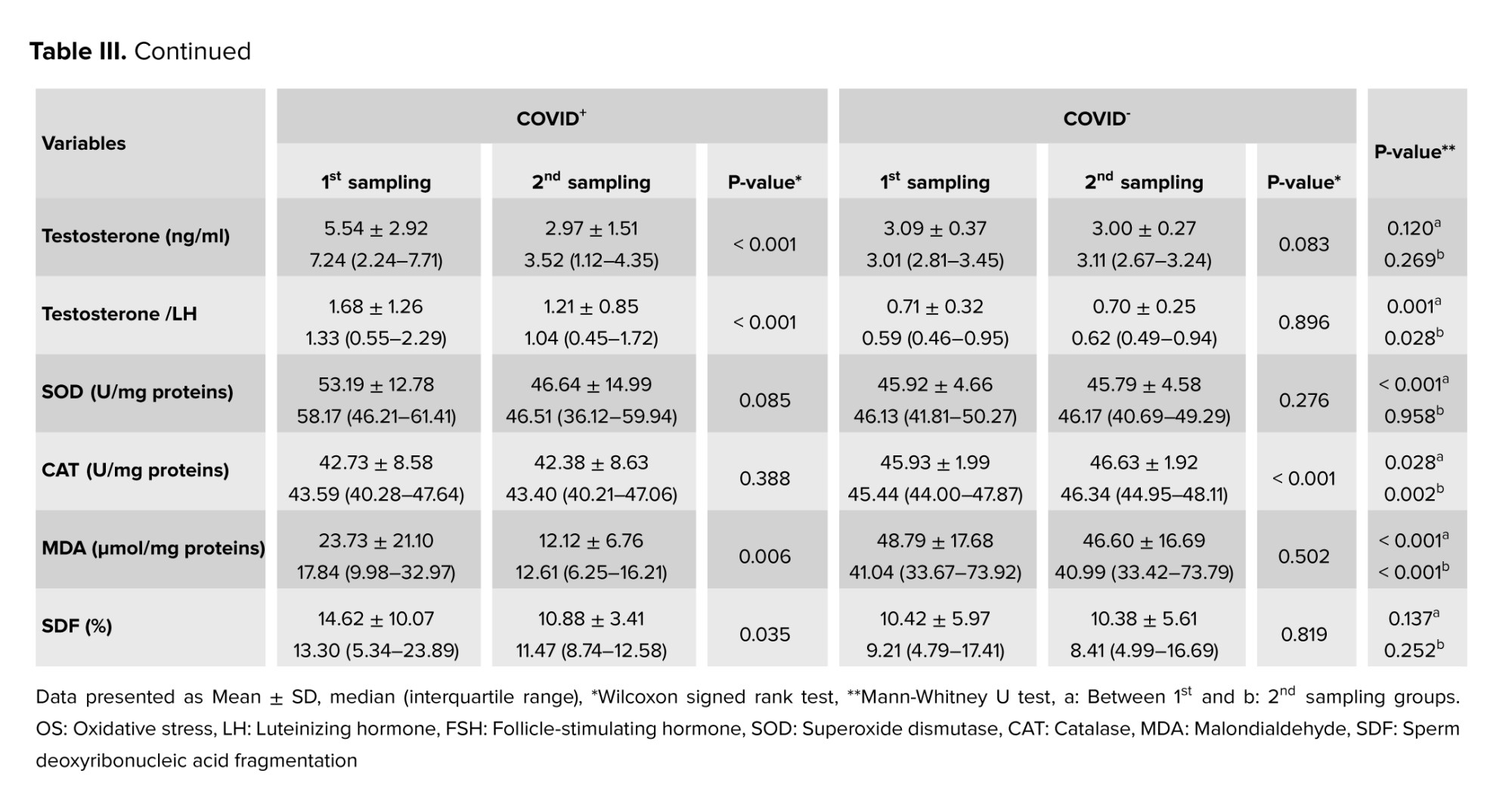

The analysis of FSH and LH levels revealed a statistically significant difference between the first and second sampling periods in the COVID+ group (p < 0.001). In contrast, no significant difference was detected between the 2 periods in the COVID- group (p > 0.05). Also, no significant difference was observed between the 2 groups in the first (i.e., acute phase) sampling (p > 0.05), but a marked difference in hormone levels emerged in the second (i.e., chronic phase) sampling episode (p < 0.001). Regarding testosterone levels, no significant difference was observed between the study groups either in the first (p = 0.120) or second (p = 0.269) sampling periods. However, a significant difference was found regarding testosterone/LH levels between the first and second periods in the COVID+ group (p < 0.001), but not in the COVID- group (p = 0.896). Additionally, significant differences were observed between the groups regarding hormonal levels during the first and second sampling periods (p > 0.05, Table III).

3.3. OS evaluation

The analysis of OS markers, including MDA levels, SOD and CAT activities, in the seminal plasma revealed significant differences between the study groups during the first sampling period (p < 0.05). During the second sampling, only MDA and CAT levels demonstrated significant differences between the 2 groups (p < 0.05). Regarding within-group differences between the 2 sampling periods, MDA level showed a statistically significant difference in the COVID+ group and CAT activity in the COVID- group (p < 0.05). From these observations, it might be hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 could reduce the levels of antioxidants in the long term, therefore adversely affecting male fertility, particularly developing spermatozoa.

3.4. Sperm chromatin structure

There was a notable increase in spermatozoa DNA damage in semen samples collected during the acute phase of the COVID-19 infection. An abnormal SDF was observed in the first sampling period (14.62 ± 10.07) compared to the second sampling (10.88 ± 3.41) in the COVID+ group (p = 0.035). However, no significant change was observed in SDF in the COVID- group. Additionally, no statistically significant differences were observed regarding SDF between the 2 groups during either the first or second sampling episode.

3.5. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in semen

After performing RT-PCR, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in none of the 70 collected semen samples, neither in the acute (i.e., first 2 wk of diagnosis) nor in the chronic (75 days on average after a nasopharyngeal positive PCR test) phase.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicated that the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 could temporarily disrupt semen quality, OS parameters, and male hormone levels (secondary hypogonadism) during the acute phase of the infection. However, according to our observations, these adverse effects tend to improve over time and during the chronic phase, which likely reflects the protective role of vaccination in mitigating devastating COVID-19 outcomes on men’s reproductive system.

The short- and long-term effects of the Omicron variant on semen quality are deterministic for men who seek natural or assisted conception, warranting more studies to decipher the potentially wider consequences of the Omicron variant on semen and sperm parameters (18). As a positive aspect of this study, the case and control participants had a similar mean age of 37 yr, which is relevant since serum testosterone levels decline with age (19).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and type 2 trans membrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) act as entry points for COVID-19 into testicular cells and are important for spermatogenesis (20). Basigin and cathepsin L in Leydig cells can also mediate viral invasion (21). Therefore, these receptors facilitate the direct effects of the virus on spermatogenesis. Rarely, virus RNA may be found in the semen of men with severe COVID-19 (22). Although the virus can cross the blood-testis barrier during acute disease, the lack of significant ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression on testicular cells likely leads to the rapid disappearance of the virus RNA from the semen of affected men (15, 22). Previous studies found no virus RNA in the semen of non-hospitalized vaccinated men, neither immediately after a positive PCR test nor during a 75-day follow-up. Similar findings were reported for non-vaccinated men, with RNA detection occurring as early as 6-8 days and as late as 181 days post-infection (15, 23). Here, we found no virus RNA in semen samples collected during the acute or chronic phases of the disease.

The absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in semen cannot rule out the susceptibility of the testicular tissue to COVID-19. According to conventional semen analysis, sperms with proper morphology and motility may not be fully competent for fertilization, requiring more evaluations especially for sperm DNA (24). In the current study, DNA fragmentation index (DFI) analysis showed significant sperm DNA damage during the acute phase compared to the chronic phase of the infection. Evidence suggests decreased semen quality in moderately ill infected patients, primarily affecting sperm concentration and motility (15). The most significant impact on sperm quality was observed shortly after recovery (23). While no effect on sperm concentration was detected, all motility parameters were adversely affected during the acute phase (25), with some improvements during the medium-long phase but without complete reversal. The impact of COVID-19 on sperm morphology remains inconclusive (23). Our study indicated that during the acute phase, DFI did not exceed the critical threshold or fluctuate during the chronic phase. It was reported that sperm quality impairment was not correlated with COVID-19 symptom severity (23). Including fever during acute infection (26), arguing that fever was not associated with sperm characteristics during the chronic phase (27).

In this study, total, grade A and grade B motility showed significant reductions during the acute phase. In contrast, significant improvements were observed in spermatozoa DNA damage during the chronic phase. A systematic review suggested that these changes were linked to inflammatory responses and fever (28). Even brief fever episodes can significantly alter sperm parameters and lead to spermatogonia destruction (29).

Sperm abnormalities were reported to correlate with the levels of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G antibodies against spike 1 and the receptor-binding domain of spike 1 (23). Discrepancies between our findings and previous studies may stem from the protective effects of vaccination, likely by reducing both SARS-CoV-2 load and antibody titers. The direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 on spermatogenesis are mediated through ACE2 expressed on spermatogenic cells (21, 30). Additionally, Basigin and cathepsin L in Leydig cells may disrupt testosterone production (30).

Bhasin and colleagues found that pituitary gland and hypothalamus disorders can lead to secondary hypogonadism (31). These brain regions express ACE2, making them potential COVID-19 targets (32). Thus, low testosterone and gonadotropin levels may result from the effects of COVID-19 on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and testes (33). Secondary hypogonadism has been reported in men recovered from COVID-19, characterized by slight FSH elevation as a sign of hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction (30). However, secondary hypogonadism during the chronic phase of COVID-19 infection may be independent of testosterone levels, so low FSH and testosterone levels should be ruled out at baseline (34). The abnormal secretion of sex hormones appears to be linked with hospitalization duration and inflammatory markers, suggesting direct viral invasion, cytokine storm, or steroids’ inhibitory effects on testes (33). In the present study, hormonal profile assessment of vaccinated men showed the occurrence of secondary hypogonadism 75 days after diagnosis. Considering the high incidence of secondary hypogonadism among COVID-19 patients, protective role of vaccination may be merely against primary but not secondary hypogonadism (33, 34).

COVID-19-associated inflammation has been shown to cause OS in sperms. Lipid peroxidation can impair the motility and fertilization capacity of sperms (33). In our study, elevated MDA levels and DFI in the acute phase of the disease were associated with altered CAT and SOD activity. Increased SOD activity may represent a compensatory mechanism during acute infection. Despite fluctuations in SOD and CAT levels, reversal of MDA and DFI indicated the resolution of inflammation in sperms post-recovery.

One limitation of the current study included the lack of evaluation of serum prolactin and inflammatory mediators.

5. Conclusion

Vaccinated men infected with the Omicron variant of COVID-19 showed impaired semen quality parameters, increased oxidative damage, and reduced testosterone levels during the acute phase of the infection. These observations could partly be explained by persistent fever and testicular inflammation, leading to secondary hypogonadism. Vaccination appears to reduce the viral load and virus-directed IgG antibodies, possibly preventing primary hypogonadism. Understanding how different SARS-CoV-2 variants affect the male reproductive system can enhance our knowledge of virus-host interactions.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

N. Majidipour: Planned the study, participated in design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. F. Pourmotahari performed the statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript. S. Sabbagh and B. Azizolahi: Carried out the laboratory tests, participated in design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. H. Nazarian: Participated in design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Men’s Health and Reproductive Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, participants and the staff at Ganjavian hospital and Emam Ali Clinical Center, Dezful, Iran for their support, cooperation, and assistance throughout the research process. Also, this article does not use artificial intelligence in any part of the process, including translation, editing, or grammar checking.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began with an initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread worldwide (1). Data reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates the vast scale of the pandemic: by April 12, 2023, a total of 762,791,152 COVID-19 infections and 6,897,025 related deaths had been officially confirmed across the globe (2).

COVID-19 predominantly affects the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous systems (3), but its impact extends to the immune system, often leading to excessive inflammation and a cytokine storm (4). 5 variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are classified as variants of concern by the WHO, including alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and Omicron (5). In November 2021, WHO identified the “Omicron” variant, and by January 6, 2022, this variant was confirmed in 149 countries, leading to a significant global increase in cases (6).

The virus targets cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (7), which is found not only in the respiratory system but also in the reproductive system. This discovery raised concerns about the potential impact of the virus on male fertility, with evidence suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 could affect semen quality and male reproductive function (8).

Men infected with COVID-19 have shown reduced sperm quality, potentially corresponding to either viral load or severity of the disease. However, some studies indicate that pre-existing fertility issues may contribute to this impairment (9). Men have also been reported to be more vulnerable to develop severe/fatal COVID-19 and impaired fertility than women, but the underlying reasons for this phenomenon remain unknown, warranting further investigations (10, 11). A study indicates that COVID-19 may cause orchitis, leading to oxidative stress, disrupted sperm production, and germ cell death, which ultimately reduces sperm quality (12). Furthermore, oxidative stress (OS) damages testicular function at macroscopic and microscopic levels. This manifests as lipid peroxidation on sperm membranes and sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation (SDF) within the spermatozoa (13). A recent study has shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection negatively affects semen parameters, including SDF and OS markers, even several months after diagnosis (14). Similarly, another study revealed that sperm concentration and motility were significantly reduced in men recovered from mild COVID-19 infection compared to a healthy control group (15). Research underscores that SARS-CoV-2 can disturb both somatic and germ cells within testes, highlighting the critical need for additional studies to fully comprehend the short- and long-term ramifications of the virus on male fertility (16).

The present study aimed to investigate the acute and long-term effects of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 virus on several aspects of male reproductive function by analyzing semen parameters, OS markers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT), as well as direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 in semen using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Additionally, blood levels of gonadotropin hormones, such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and testosterone, as well as SDF, were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This matched case-control study was carried out on 70 men at Ganjavian hospital in Dezful, Iran, to compare semen parameters, gonadotropin hormone levels, OS markers, and SDF between men with confirmed COVID-19 (cases) and healthy controls. Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method from adult men. The participants were then divided into 2 groups: the COVID+ group (cases, n = 35) and the COVID- group (controls, n = 35). Data collection and follow-up were conducted between July 2022 and January 2023.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The COVID+ group included married men aged 25-55 yr with at least one child, all of whom tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR. The COVID- group comprised age-matched healthy male participants with negative RT-PCR results for COVID-19 and no clinical symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, and dyspnea) at the time of enrollment. To address potential confounding variables such as age, matching was applied between COVID+ and COVID- groups (1:1 ratio).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: incomplete follow-up (i.e., failure to complete scheduled clinical or laboratory assessments), sexually transmitted infections (human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B/C, syphilis, or genital herpes diagnosed via serological testing or PCR), testicular abnormalities (palpable varicocele grade I-III), testicular atrophy (volume < 12 mL), history of prior testicular surgery (e.g., orchidopexy, varicocelectomy, or inguinal hernia repair documented by medical records), scrotal trauma (history of scrotal injury within the past year), acute inflammation (acute epididymitis and orchitis), history of childhood mumps (self-reported or medically documented mumps-associated orchitis), malignancies (present or past diagnosis of testicular cancer, leukemia, or lymphoma), using medications for reproductive system abnormalities (androgen supplements such as testosterone, anabolic steroids, or chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide within the past 6 months), substance use (current smoking > 5 cigarettes/day or alcohol consumption > 14 units/wk), endocrine disorders (diabetes mellitus: fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%; thyroid dysfunction: thyroid-stimulating hormone < 0.4 or > 4.0 mIU/L along with abnormal free thyroxine levels), and antibiotic use within the past 3 months for bacterial prostatitis, urinary tract infections, or respiratory infections.

2.3. Data sources/collection

2.3.1. Checklist

A structured checklist titled “Participant Information Checklist” was developed to gather demographic data and medical/surgical history of the participants. Individuals with a self-reported history of any medical condition or prior surgery were excluded from the study.

2.3.2. Semen sampling

Semen samples were collected from each participant during the acute phase (from the time of a positive RT-PCR result to 2 wk post-diagnosis) and the chronic phase (75 days post-diagnosis).

2.3.3. Semen analysis protocol

After 3 to 5 days of sexual abstinence, semen samples were collected by masturbation into sterile falcon tubes. The samples were incubated at 37°C for 30-60 min in a CO₂ incubator (set to 5% CO₂ and 95% relative humidity) to allow for liquefaction. After semen liquefaction, key sperm parameters (pH, volume, sperm count, motility percentage, and motion characteristics) were manually assessed by 2 expert observers and evaluated based on established WHO recommendations (17). Briefly, pH was measured using a pH paper and compared with a calibration strip. Sperm count was determined under a microscope using a hemocytometer after dilution (1:20, one part of semen mixed with 19 parts of a diluent, sodium bicarbonate solution). Then 10 µL of the diluted sample was loaded into a hemocytometer (a specialized chamber with a grid pattern that facilitates counting), and spermatozoa in several squares of the grid were counted. Finally, sperm count was calculated by multiplying the dilution factor by the volume of the chamber. Sperm counts ≥ 15 × 106/mL were considered normal. To assess sperm morphology, the semen samples were centrifuged, and the resulting pellets were used to prepare smears, which were then stained using both Papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin techniques. The stained slides were then examined under a light microscope at ×100 magnification. Sperm morphology was assessed by calculating the percentage of sperms with normal vs. abnormal shapes. A normal result was considered when morphologically intact sperms were ≥ 30%. Finally, sperm motility was categorized and assessed as follows: rapidly progressive (type A), slowly progressive (type B), non-progressive (type C), or immotile (type D). Based on WHO recommendations, normal fertility corresponds to ≥ 50% motility for A- and B-type sperms.

2.3.4. SARS-CoV-2 detection in semen

For SARS-CoV-2 detection, a separate aliquot of the semen sample was used. Total RNA was extracted from 140 µL of this aliquot with the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The extracted RNA was eluted in 30 µL of elution buffer. SARS-CoV-2 detection was then performed using the Pishtaz Teb Zaman Molecular COVID-19 RT-PCR kit (Iran), which targets the ORF1ab gene, the nucleoprotein (N) gene, and the RNase P gene as an internal control.

2.3.5. Hormone testing

Venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from each participant. Hormone levels, including FSH, LH, and testosterone, were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Pishtaz Teb Zaman, Iran).

2.3.6. OS evaluation

OS markers, including SOD, MDA, and CAT, were assessed in semen samples using diagnostic kits (ZellBio, Germany). These tests were performed on the liquid portion of semen samples after centrifugation and separation from sperms.

2.3.7. SDF assessment

The quality of SDF was assessed using the sperm chromatin dispersion method using a specialized kit manufactured by Shams Azma CO., Iran. The test involved preparing a smear slide from diluted semen samples, incubating the slide with appropriate buffers provided by the kit, dehydrating the slide with alcohol, and examining it under a light microscope. The percentage of SDF was determined by counting 500 sperms at x100 magnification.

2.4. Bias assessment

The risk of potential bias was addressed in the present study as follows:

2.4.1. Selection bias

This study used the convenience sampling method. This method could have led to a biased sample that might not be fully representative of the broader population of men affected by COVID-19. Specifically, the sample might not account for individuals who were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms and, therefore, did not seek medical attention.

2.4.2. Information bias

This study relied on self-reported data for inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thus, there could be a risk that some participants failed to accurately recall or report this information, leading to potential misclassification of participants.

2.4.3. Potential impact of the COVID-19 variant

This study focused on the Omicron variant; however, other variants might also affect men’s reproductive health. Therefore, the results of this study may not be fully generalizable to other variants of SARS-CoV-2 regarding Omicron variant’s distinct characteristics compared to other strains.

2.5. Sample size

The sample size was calculated considering a type I error (α) of 0.05, a power of 0.9 (1-β), and the 2 variables of sperm count and volume as the target outcomes in the study’s objectives. In this design, the maximum sample size was calculated as n = 34 per group. The dropout rate was estimated at 20%.

The symbols S1 and S2 denote the standard deviations, while µ1 and µ2 represent the means for group 1 and group 2, respectively.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Vice-Chancellor in Research Affairs, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1401.071). Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to present continuous variables, and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. To compare categorical variables between the COVID+ and COVID- groups, the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were employed, and continuous variables were compared between the groups using the Mann-Whitney U test based on the results of normality assessment according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. Semen parameters and laboratory variables at the first and second sampling phases were compared by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). 2-sided p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ characteristics

A total of 70 men with a mean age of 37.60 ± 6.38 yr were enrolled in this study. Demographic features and vaccination status in the COVID+ and COVID- groups have been shown in table I.

Participants in the 2 groups had no significant differences in terms of age, educational levels, job status, number of children, and vaccination history. All non-hospitalized participants reported at least one COVID-19 symptom during the acute phase of the infection. None of the individuals enrolled in the current study had sexually transmitted or other diseases such as AIDS, varicocele, etc.

The brands of COVID-19 vaccines received by the participants for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd doses were as follows:

Dose 1: Sinopharm (72.9%), Sputnik V (15.7%), AstraZeneca (8.6%), and Bharat Biotech (2.8%).

Dose 2: no vaccination (4.3%), Sinopharm (62.9%), Sputnik V (8.6%), AstraZeneca (5.7%), Barekat (5.7%), and Bharat Biotech (2.8%).

Dose 3: no vaccination (27.1%), Sputnik V (14.3%), Sinopharm (25.7%), and PastoCovac (32.9%).

According to the results, significant within-group differences were observed in the COVID+ group between the 1st (i.e., acute phase) and 2nd (i.e., chronic phase) sampling periods regarding semen pH and sperm motility categories (i.e., fast forward motility; class A, slow forward motility; class B, no forward progression; class C, and non-motile) as shown in table II.

The findings of semen analysis showed that significant differences were observed between the COVID+ and COVID- groups both in the first and second sampling periods in terms of sperm parameters: motility, fast forward motility (class A), slow forward motility (class B, only in the first phase), no forward progression (class C), non-motile, as well as morphology. Total motility was significantly reduced during the acute phase of the infection (49.37 ± 18.01%) when compared to the chronic phase (64.08 ± 14.16%), indicating that sperm motility could be adversely affected during the early stages of the infection, with recovery occurring thereafter. Statistically significant differences were also observed in sperm morphology between the COVID+ and COVID- groups during the acute (p = 0.001) and chronic (p = 0.015) phases.

3.2. Hormone testing

The analysis of FSH and LH levels revealed a statistically significant difference between the first and second sampling periods in the COVID+ group (p < 0.001). In contrast, no significant difference was detected between the 2 periods in the COVID- group (p > 0.05). Also, no significant difference was observed between the 2 groups in the first (i.e., acute phase) sampling (p > 0.05), but a marked difference in hormone levels emerged in the second (i.e., chronic phase) sampling episode (p < 0.001). Regarding testosterone levels, no significant difference was observed between the study groups either in the first (p = 0.120) or second (p = 0.269) sampling periods. However, a significant difference was found regarding testosterone/LH levels between the first and second periods in the COVID+ group (p < 0.001), but not in the COVID- group (p = 0.896). Additionally, significant differences were observed between the groups regarding hormonal levels during the first and second sampling periods (p > 0.05, Table III).

3.3. OS evaluation

The analysis of OS markers, including MDA levels, SOD and CAT activities, in the seminal plasma revealed significant differences between the study groups during the first sampling period (p < 0.05). During the second sampling, only MDA and CAT levels demonstrated significant differences between the 2 groups (p < 0.05). Regarding within-group differences between the 2 sampling periods, MDA level showed a statistically significant difference in the COVID+ group and CAT activity in the COVID- group (p < 0.05). From these observations, it might be hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 could reduce the levels of antioxidants in the long term, therefore adversely affecting male fertility, particularly developing spermatozoa.

3.4. Sperm chromatin structure

There was a notable increase in spermatozoa DNA damage in semen samples collected during the acute phase of the COVID-19 infection. An abnormal SDF was observed in the first sampling period (14.62 ± 10.07) compared to the second sampling (10.88 ± 3.41) in the COVID+ group (p = 0.035). However, no significant change was observed in SDF in the COVID- group. Additionally, no statistically significant differences were observed regarding SDF between the 2 groups during either the first or second sampling episode.

3.5. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in semen

After performing RT-PCR, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in none of the 70 collected semen samples, neither in the acute (i.e., first 2 wk of diagnosis) nor in the chronic (75 days on average after a nasopharyngeal positive PCR test) phase.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicated that the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 could temporarily disrupt semen quality, OS parameters, and male hormone levels (secondary hypogonadism) during the acute phase of the infection. However, according to our observations, these adverse effects tend to improve over time and during the chronic phase, which likely reflects the protective role of vaccination in mitigating devastating COVID-19 outcomes on men’s reproductive system.

The short- and long-term effects of the Omicron variant on semen quality are deterministic for men who seek natural or assisted conception, warranting more studies to decipher the potentially wider consequences of the Omicron variant on semen and sperm parameters (18). As a positive aspect of this study, the case and control participants had a similar mean age of 37 yr, which is relevant since serum testosterone levels decline with age (19).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and type 2 trans membrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) act as entry points for COVID-19 into testicular cells and are important for spermatogenesis (20). Basigin and cathepsin L in Leydig cells can also mediate viral invasion (21). Therefore, these receptors facilitate the direct effects of the virus on spermatogenesis. Rarely, virus RNA may be found in the semen of men with severe COVID-19 (22). Although the virus can cross the blood-testis barrier during acute disease, the lack of significant ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression on testicular cells likely leads to the rapid disappearance of the virus RNA from the semen of affected men (15, 22). Previous studies found no virus RNA in the semen of non-hospitalized vaccinated men, neither immediately after a positive PCR test nor during a 75-day follow-up. Similar findings were reported for non-vaccinated men, with RNA detection occurring as early as 6-8 days and as late as 181 days post-infection (15, 23). Here, we found no virus RNA in semen samples collected during the acute or chronic phases of the disease.

The absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in semen cannot rule out the susceptibility of the testicular tissue to COVID-19. According to conventional semen analysis, sperms with proper morphology and motility may not be fully competent for fertilization, requiring more evaluations especially for sperm DNA (24). In the current study, DNA fragmentation index (DFI) analysis showed significant sperm DNA damage during the acute phase compared to the chronic phase of the infection. Evidence suggests decreased semen quality in moderately ill infected patients, primarily affecting sperm concentration and motility (15). The most significant impact on sperm quality was observed shortly after recovery (23). While no effect on sperm concentration was detected, all motility parameters were adversely affected during the acute phase (25), with some improvements during the medium-long phase but without complete reversal. The impact of COVID-19 on sperm morphology remains inconclusive (23). Our study indicated that during the acute phase, DFI did not exceed the critical threshold or fluctuate during the chronic phase. It was reported that sperm quality impairment was not correlated with COVID-19 symptom severity (23). Including fever during acute infection (26), arguing that fever was not associated with sperm characteristics during the chronic phase (27).

In this study, total, grade A and grade B motility showed significant reductions during the acute phase. In contrast, significant improvements were observed in spermatozoa DNA damage during the chronic phase. A systematic review suggested that these changes were linked to inflammatory responses and fever (28). Even brief fever episodes can significantly alter sperm parameters and lead to spermatogonia destruction (29).

Sperm abnormalities were reported to correlate with the levels of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G antibodies against spike 1 and the receptor-binding domain of spike 1 (23). Discrepancies between our findings and previous studies may stem from the protective effects of vaccination, likely by reducing both SARS-CoV-2 load and antibody titers. The direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 on spermatogenesis are mediated through ACE2 expressed on spermatogenic cells (21, 30). Additionally, Basigin and cathepsin L in Leydig cells may disrupt testosterone production (30).

Bhasin and colleagues found that pituitary gland and hypothalamus disorders can lead to secondary hypogonadism (31). These brain regions express ACE2, making them potential COVID-19 targets (32). Thus, low testosterone and gonadotropin levels may result from the effects of COVID-19 on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and testes (33). Secondary hypogonadism has been reported in men recovered from COVID-19, characterized by slight FSH elevation as a sign of hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction (30). However, secondary hypogonadism during the chronic phase of COVID-19 infection may be independent of testosterone levels, so low FSH and testosterone levels should be ruled out at baseline (34). The abnormal secretion of sex hormones appears to be linked with hospitalization duration and inflammatory markers, suggesting direct viral invasion, cytokine storm, or steroids’ inhibitory effects on testes (33). In the present study, hormonal profile assessment of vaccinated men showed the occurrence of secondary hypogonadism 75 days after diagnosis. Considering the high incidence of secondary hypogonadism among COVID-19 patients, protective role of vaccination may be merely against primary but not secondary hypogonadism (33, 34).

COVID-19-associated inflammation has been shown to cause OS in sperms. Lipid peroxidation can impair the motility and fertilization capacity of sperms (33). In our study, elevated MDA levels and DFI in the acute phase of the disease were associated with altered CAT and SOD activity. Increased SOD activity may represent a compensatory mechanism during acute infection. Despite fluctuations in SOD and CAT levels, reversal of MDA and DFI indicated the resolution of inflammation in sperms post-recovery.

One limitation of the current study included the lack of evaluation of serum prolactin and inflammatory mediators.

5. Conclusion

Vaccinated men infected with the Omicron variant of COVID-19 showed impaired semen quality parameters, increased oxidative damage, and reduced testosterone levels during the acute phase of the infection. These observations could partly be explained by persistent fever and testicular inflammation, leading to secondary hypogonadism. Vaccination appears to reduce the viral load and virus-directed IgG antibodies, possibly preventing primary hypogonadism. Understanding how different SARS-CoV-2 variants affect the male reproductive system can enhance our knowledge of virus-host interactions.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

N. Majidipour: Planned the study, participated in design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. F. Pourmotahari performed the statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript. S. Sabbagh and B. Azizolahi: Carried out the laboratory tests, participated in design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. H. Nazarian: Participated in design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Men’s Health and Reproductive Health Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, participants and the staff at Ganjavian hospital and Emam Ali Clinical Center, Dezful, Iran for their support, cooperation, and assistance throughout the research process. Also, this article does not use artificial intelligence in any part of the process, including translation, editing, or grammar checking.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Andrology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |