Fri, Jan 30, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 10 (October 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(10): 843-852 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1402.024

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Elyasi M, Shirkhoda S A, Fallah Zadeh H, Rouhbakhsh A. The prevalence of postpartum depression and associated characteristics in fathers of newborns in Yazd City in 2023: A cross-sectional study. IJRM 2025; 23 (10) :843-852

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3617-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3617-en.html

1- Department of Psychiatry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Psychiatry, Research Center of Addiction and Behavioral Sciences, Non-Communicable Diseases Research Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Research Center for Healthcare Data Modeling, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Research Center of Addiction and Behavioral Sciences, Non-Communicable Diseases Research Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,ashrafrouhbakhsh@yahoo.com; a.rouhbakhsh@ssu.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychiatry, Research Center of Addiction and Behavioral Sciences, Non-Communicable Diseases Research Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Research Center for Healthcare Data Modeling, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Research Center of Addiction and Behavioral Sciences, Non-Communicable Diseases Research Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 394 kb]

(357 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (326 Views)

1. Introduction

Depression is a prevalent mental disorder affecting both mothers and fathers during pregnancy and childbirth (1). Prenatal and postnatal depression resembles other forms of depression, characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest, fatigue, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts (2). While postpartum depression (PPD) in women has been extensively studied (3), emerging evidence suggests that men can also experience depression following childbirth, albeit typically starting later than in women. Fathers may exhibit irritability, emotional withdrawal, risk-taking behaviors or substance use, somatic complaints such as fatigue or headaches, and difficulties in bonding with the infant, rather than overt sadness or tearfulness (4).

Pregnancy can be stressful for both parents; men may develop subtle depression-like symptoms due to emotional bonds, often expressed as isolation, aggression, anxiety, or substance abuse (5). The prevalence of paternal depression in Western countries is estimated to range from 24-25% (6), particularly among first-time fathers, peaking within the first 6 months postpartum due to fatigue and stress from caregiving. These gender-specific symptoms are frequently shaped by male gender role stress, including societal expectations to remain stoic and emotionally restrained, which can lead to feelings of inadequacy and reluctance to seek help (7). Furthermore, paternal depression is closely linked to maternal depression, with studies indicating that 8.4-10% of fathers experience depression during pregnancy, and 6.6-13.6% postpartum (8). This condition can adversely affect child development and parental involvement (9).

Factors contributing to paternal depression include unemployment, poor marital relationships, low socioeconomic status, and stressful life events (10). Despite the significance of paternal mental health, most research has focused on maternal PPD, leaving a gap in understanding fathers’ experiences and help-seeking behaviors. Perceived social support is a crucial factor in mitigating PPD in fathers (11).

Goodman and Garber found that the incidence of paternal depression can vary significantly, with community samples showing rates from 1.2-25.5% and higher rates (24-50%) among men whose partners faced PPD (12). Maternal depression is the strongest predictor of paternal depression during this period, emphasizing the interconnectedness of parental mental health (13). A study highlighted that 11.7% of fathers exhibited depressive symptoms, revealing a positive correlation between perceived stress and PPD, while perceived social support showed a negative correlation (14).

The model predicting PPD based on stress and social support, with vulnerable personality traits as mediators, accounted for 25% of the variance in paternal PPD (15).

The high comorbidity between paternal and maternal PPD can lead to emotional and behavioral issues in children and increased marital conflict (16). Hormonal changes in fathers, including variations in testosterone and cortisol levels, may contribute to the risk of developing PPD (17). A study in Japan reported that 17% of fathers experienced depressive symptoms within the first 3 months postpartum, underscoring the importance of early assessment and support for fathers (18).

In Iran, as fathers assume caregiving roles, safeguarding their mental health is important. Due to paternal depression’s complexity, further research is needed on its prevalence and causes, especially in Yazd’s 2023 context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study involved 270 fathers aged ≥ 18 who referred to 4 healthcare centers in Yazd, Iran for receiving postnatal care of their infants (aged ≤ 2 months) from September 2023-September 2024. Participants and healthcare centers were randomly selected.

2.2. Data collection

To assess participants depression, they were asked to fill the Edinburgh questionnaire (a demographic information questionnaire including education and xx income levels) and a questionnaire regarding the number of children in the family and the prematurity of the newborn. To ensure appropriate distribution of the selected health centers, the city was classified into 3 levels based on existing socioeconomic information: low-income, middle-income, and high-income, with 2 centers randomly chosen from each area.

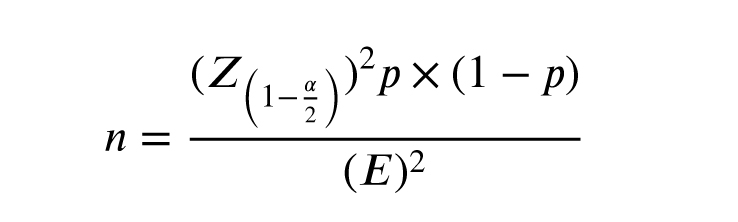

2.3. Sample size

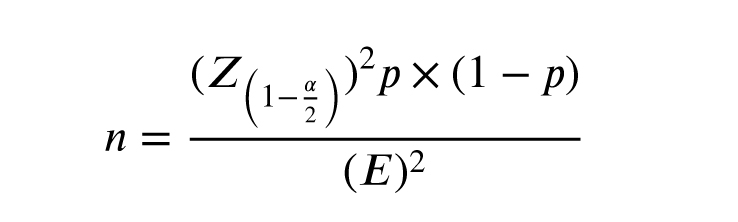

Considering a 95% confidence level, the prevalence of 26% of this disorder and an estimation error of 5.5%, 245 fathers were needed. The formula for calculating the sample size is as follows:

For greater certainty, 270 participants were included.

The variables examined in this study included the prematurity of the newborn, the sex of the newborn, and number of children, education, income level, and paternal depression.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were fathers aged ≥ 18 who were able to read and understand the questions. The infants were a maximum of 2 months old. Other inclusion criteria were residence in Yazd for access to obtain additional information if needed, willingness to participate in the study, sufficient literacy and cognitive ability to understand the questions and complete the questionnaire, which was determined by measuring the individual’s understanding of the introduction provided by the researcher, absence of significant verbal barriers that would reduce the individual’s understanding of the context and related questions. The exclusion criteria were chronic severe mental disorders or disabilities, and the inability to understand questions among fathers. Visual or hearing impairments that prevent the ability to read or hear the questionnaire questions are also exclusion criteria.

2.5. Edinburgh scale

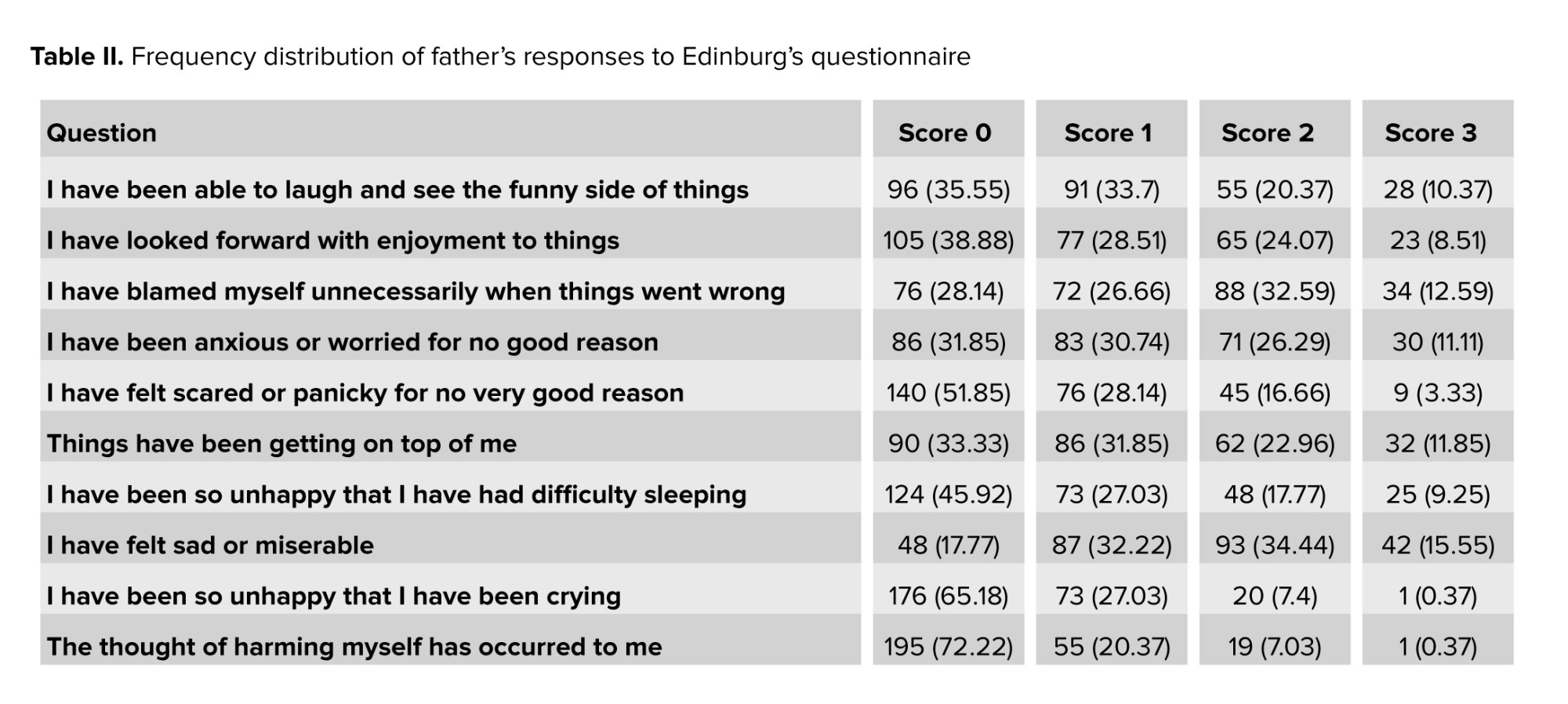

The Edinburgh PPD scale consists of 10 items. This questionnaire is designed to facilitate the diagnosis of depression from 6 wk postpartum. The score on the Edinburgh scale ranges from zero-30, with a score of 12 or higher considered indicative of PPD.

Questions 1, 2, and 4 are scored from 0-3, while questions 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 are scored from 3-0.

The Cronbach’s alpha for the Edinburgh test is 0.70, and the validity of the Edinburgh test with the Beck scale is 0.44 (19).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1402.024). The researcher explained the study process to the participants and collected the necessary information by delivering the questionnaires to individuals after obtaining written informed consent and explaining the confidentiality of the information and the objectives of the research. The information remained confidential and was used solely for research purposes.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

In this study, data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA (SPSS). Quantitative data were reported using mean and standard deviation, while qualitative data were reported using frequency and percentage. t tests and Chi-square tests were used to analyze quantitative and qualitative variables between 2 groups, and one-way ANOVA tests were used to analyze quantitative variables among more than 2 groups.

3. Results

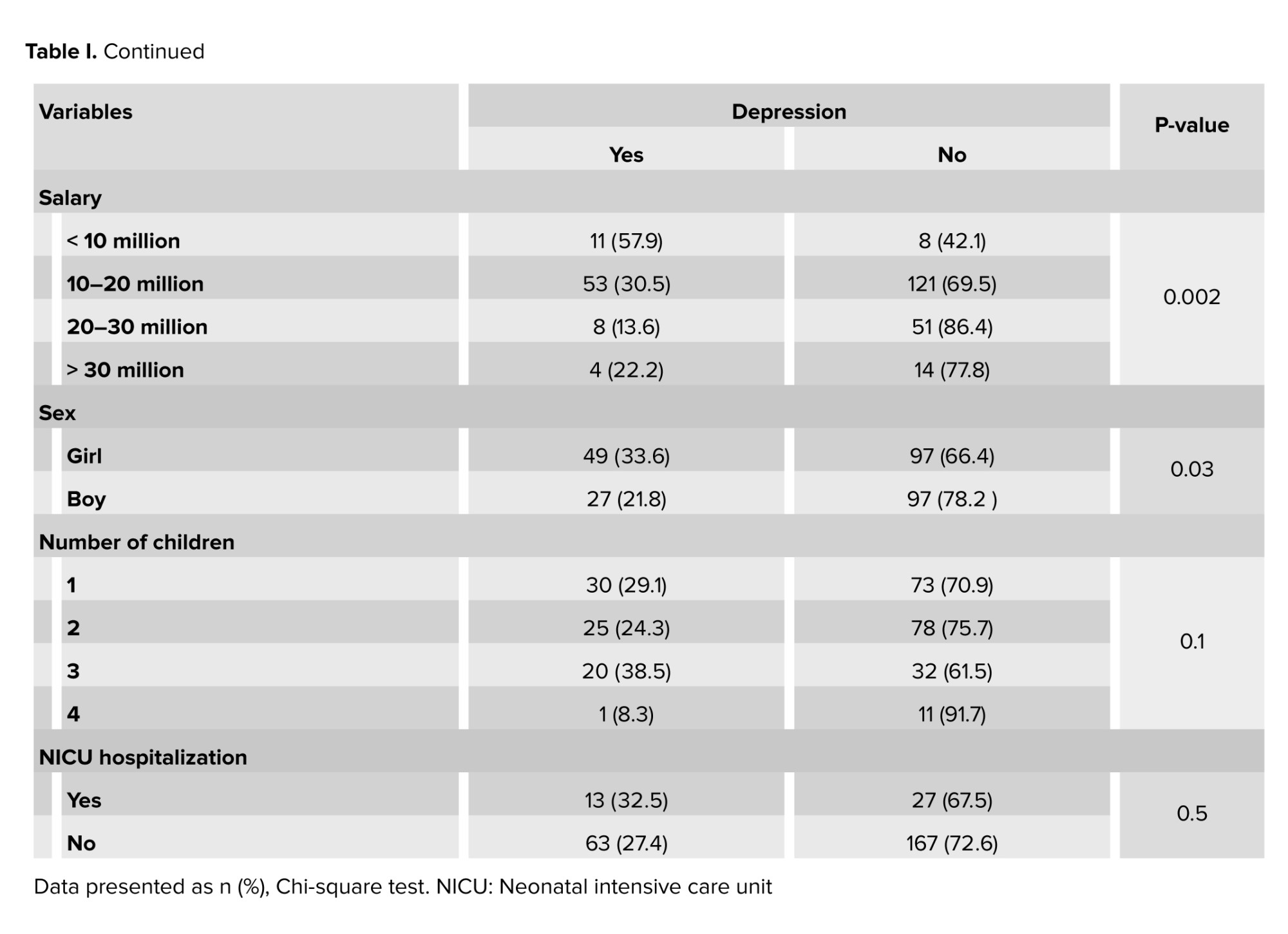

In this study, 270 fathers aged 35.84 ± 7.18 were examined. Based on education level, 164 individuals (59.6%) had an education below a diploma or had a diploma, and 106 individuals (40.4%) had academic education (bachelor’s degree or higher). Regarding monthly income, > 60% of participants had a moderate income (between 10-20 million), and high-income group were placed after. Among the children, 146 (54.1%) were girls and 124 (45.9%) were boys. Only 14.8% of the children questioned had a history of hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

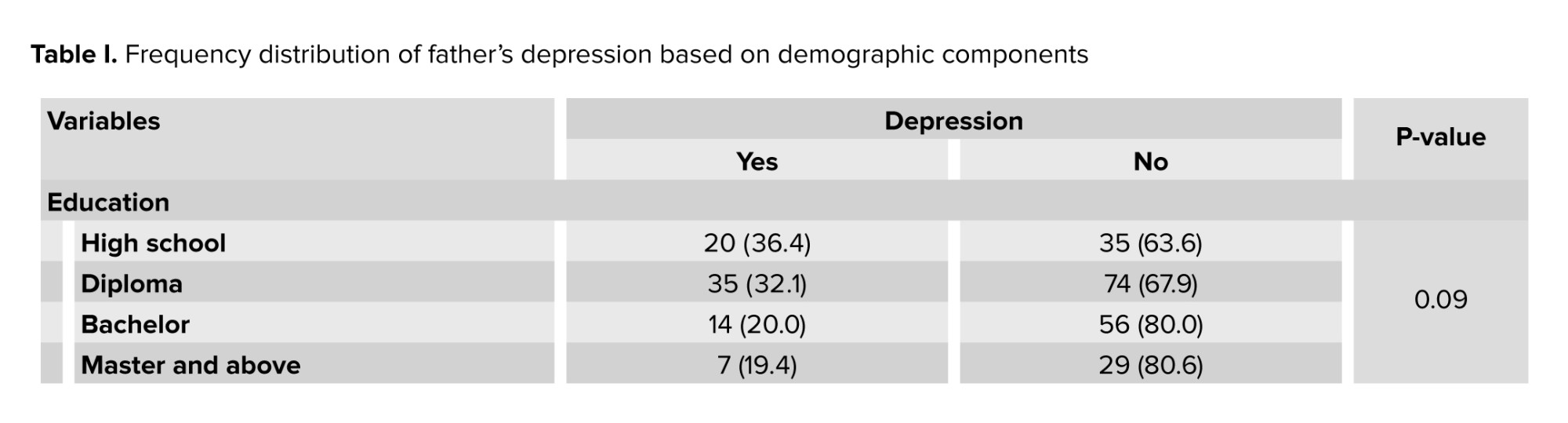

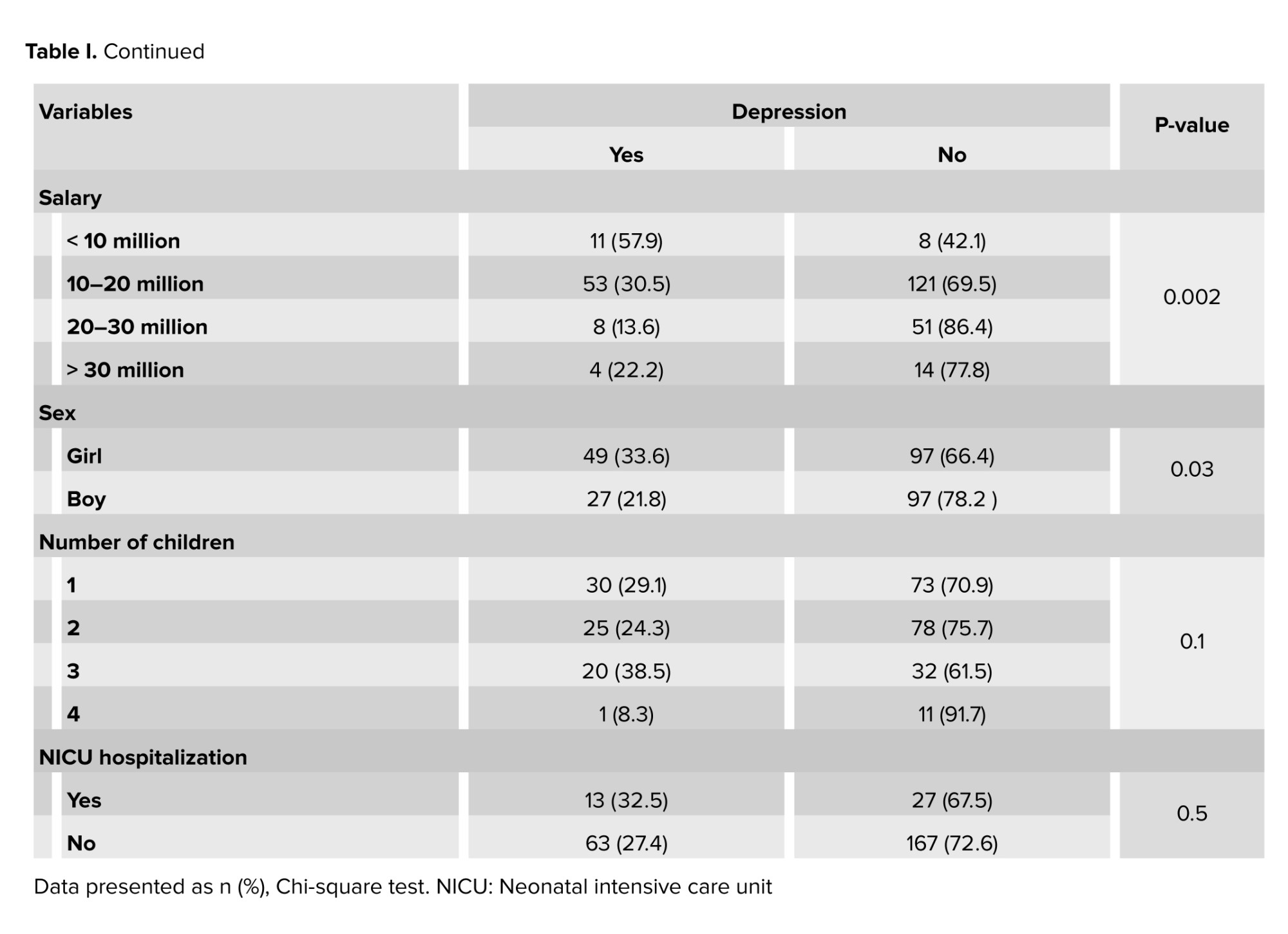

In the categorization conducted, 81 fathers (30%) were found to have depression. In examining the distribution of depression according to the fathers’ education level, no significant difference was observed between depressed individuals in regards to educational level (p = 0.09).

Considering their level of income, a meaningful negative correlation was observed between depressive scores and average monthly salary (p = 0.002).

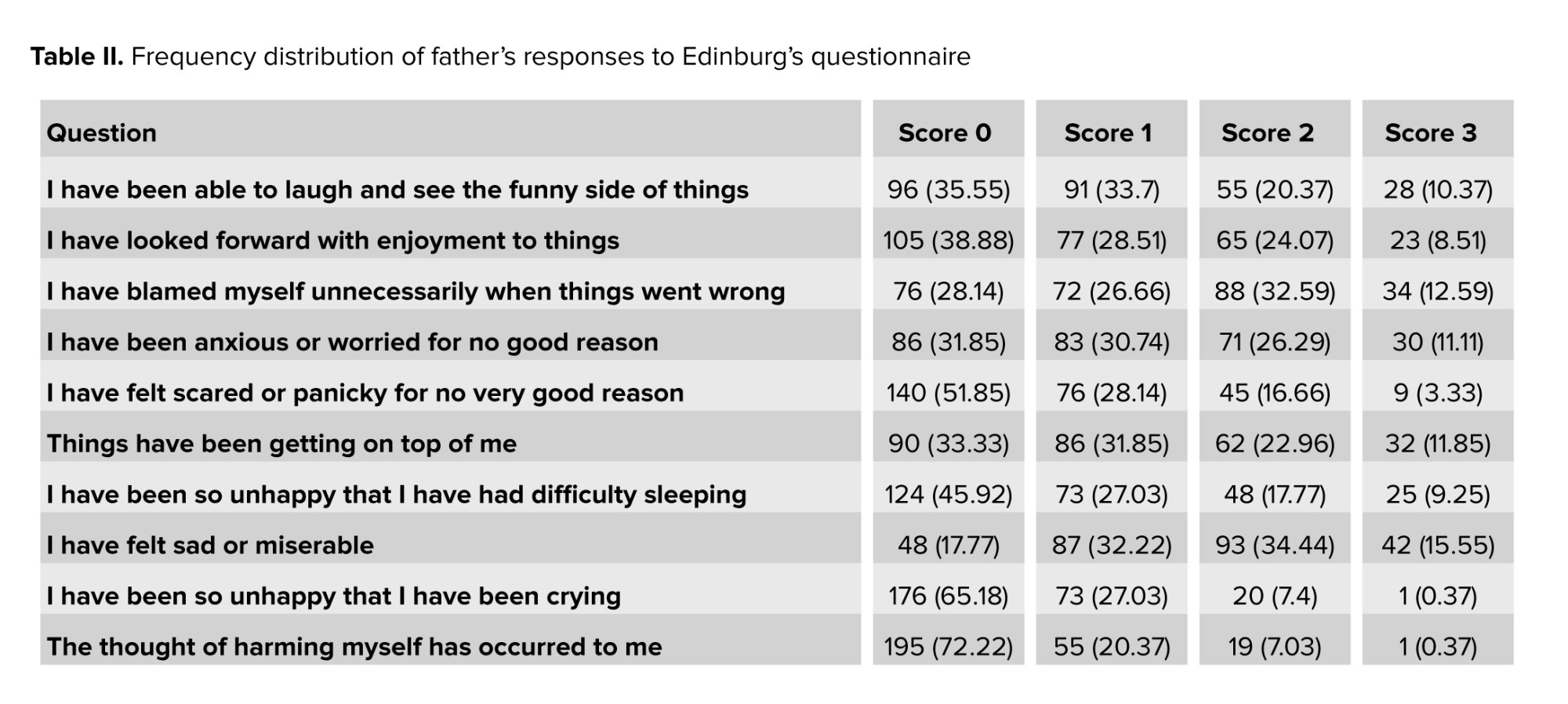

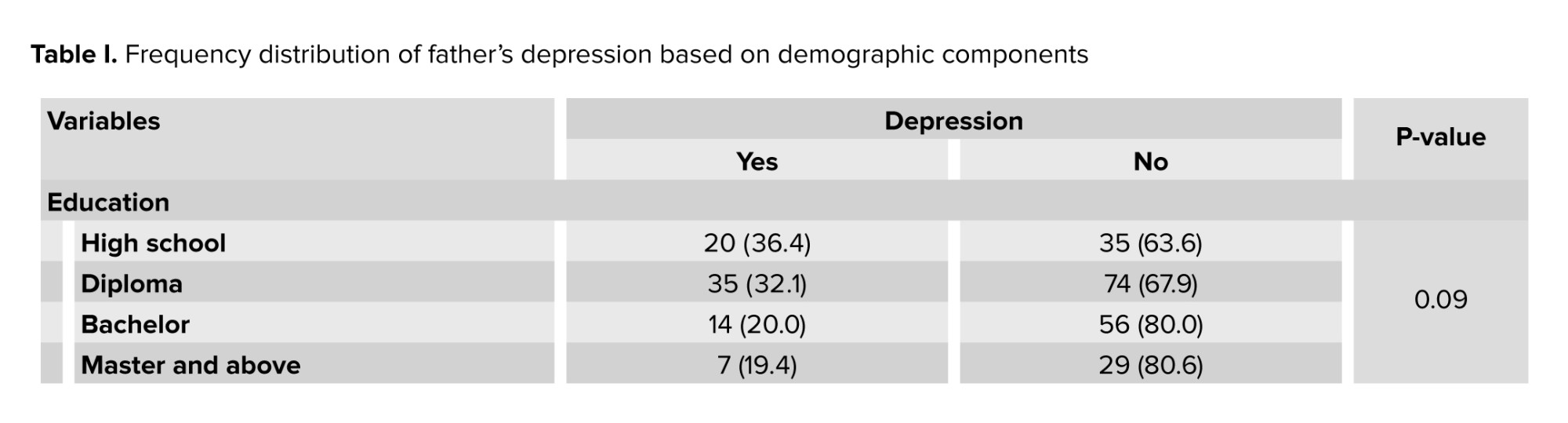

Furthermore, among fathers after childbirth, having a baby girl (p = 0.03) was related to higher depression scores significantly, while no similar correlation was observed between number of children (p = 0.1) or history of newborn NICU hospitalization and depression (p = 0.5, Table I, II).

4. Discussion

In this study, 270 fathers were examined. In the present study, 81 fathers (30%) were found to be depressed. This prevalence was less than study conducted by a previous study, which was conducted on 144 fathers; the prevalence of depression among fathers postpartum was reported to be 45.8% (20). Several factors may explain this discrepancy. First, the larger sample size in the present study may have provided a more representative estimate of the general population. Second, differences in sampling methods, timing of assessment, and regional variations in mental health awareness and support systems could have contributed to the lower observed prevalence. Additionally, increased public health attention to maternal mental health in recent years may have indirectly improved paternal coping mechanisms, reducing the severity or recognition of depressive symptoms. However, cultural factors may have played a more significant role in this context. In traditional communities such as Yazd, social norms often discourage emotional expression among men, particularly regarding psychological distress. Feelings of sadness, vulnerability, or anxiety may be perceived as signs of weakness, leading many fathers to suppress or deny such experiences. This cultural stigma not only reduces the likelihood of seeking help but may also limit men’s ability to recognize or articulate their own emotional states. Consequently, the lower prevalence observed in this study may reflect under-reporting rather than an actual reduction in depressive symptoms. In contrast, the prevalence in Western societies has been reported to be between 4% and 25%. In 2 meta-analyses, the prevalence of depression in fathers before childbirth was reported as 8.4% and 10%. In 6 other studies measuring the prevalence of depression in fathers during the postpartum period, it ranged from 6.6%-13.6% (21).

In the prevailing mental conditions during and after pregnancy, more attention has been given to depression in women and mothers than to depression in fathers. This is because the occurrence of depression in fathers can also affect all aspects of family life, including relationships with spouses and children, and fulfilling the role of fatherhood. Because various factors are associated having issues with the wife's family such as a supportive source causing depression, and particularly the economic status of poor and middle-income families as a strong predictor of depression with the onset of depression in fathers and they are different in different societies; it is possible to provide necessary training for early referral by examining risk factors during prenatal care, throughout pregnancy, at the time of childbirth, and postpartum, along with educating about the symptoms of the disease both verbally and in writing.

This study replicated findings on meta-analysis that reported prevalence of PPD, which did not show meaningful difference in terms of number of children or parity (21). In another analysis, it was shown that the monthly income of depressed fathers was significantly lower. 2 previous studies indicated that income level and economic status of the family are related to PPD in fathers (22, 23), which aligns with the results of the present study. Similar results were shown in another study (24).

Our finding that lower income is significantly linked to paternal PPD aligns with international reports. Duan et al. (14) and Fang et al. (22) both noted that financial strain increases the psychological burden on new fathers, especially in cultures that stress the father’s role as the economic provider. This is also true in Iran, where economic pressures and the high cost of raising children can heighten stress during the postpartum period. Addressing economic vulnerability with focused psychosocial support and policy measures could be an important preventive strategy.

The preference for son exists in many cultures in South, East Asia, and Africa. For example, in India, Pakistan, Egypt, and China, there is a preference for male children (24). In Bangladesh, the rate of female fetus abortion is higher, and the association of giving birth to a girl in families that desire a boy has been reported to correlate with PPD (25). The reason for this is the importance of boys in family economics and their roles in rural life and agricultural work. Additionally, boys are considered a source of strength and social security. The results of the present study were consistent with these findings. In Western countries and European cultures, due to the equality of value between genders, this correlation does not exist.

In the present study, several demographic and clinical variables played an important role in shaping paternal depression. Although the level of paternal education was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (p = 0.09), this may suggest that education alone does not offer protection against psychological distress (21). Other mediating factors such as socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs, and social support may be more influential.

Neonatal admission to the NICU also did not show a significant relationship with paternal depression (p = 0.13), despite previous studies identifying NICU admission as emotionally taxing for parents (22). In our sample, family support or prior awareness of the infant’s condition may have helped buffer the emotional impact of hospitalization.

The number of children was significantly associated with paternal depression (p = 0.01), suggesting that increased responsibilities, lower income, and reduced personal time may contribute to emotional strain. This finding is consistent with earlier research highlighting parenting load as a contributing factor (20).

Although the average age of fathers in this study was 35.84 yr, no detailed analysis was conducted regarding the role of age in the onset of depression. Future research may benefit from exploring this variable to better understand how life experience, psychological maturity, and readiness for fatherhood affect mental well-being.

The significant differences in reported prevalence may also be due to variations in tools, their non-standardization, and differing statistical methods in various studies. The prevalence of PPD in mothers remains particularly important, as maternal depression can act as a risk factor for the onset of depression in fathers, which was not examined in this study. Some literature identifies this factor as the strongest predictor of depression in fathers. The cause of its occurrence may be inadequate support from partners (mothers) during this period, leading to feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and lack of control over the situation.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One limitation of this research is that it was conducted in only one city; as studies have shown, although maternal depression has received attention and necessary interventions are being implemented in Iran, paternal depression has not received adequate attention despite its importance for child development and family dynamics. Therefore, further studies on a broader scale and repeated correlation of known related and unrelated variables in this research are essential. It is also suggested that while examining mothers for PPD, questionnaires regarding fathers should also be completed to determine whether, similar to Western literature, maternal depression can be a strong predictor of depression in fathers in Iranian society.

5. Conclusion

The present study examined PPD among fathers and showed that this issue is significantly prevalent not only among mothers, but also among fathers. The findings indicated that fathers, especially in difficult economic and social conditions, and those experiencing fatherhood for the first time, are at greater risk of developing PPD. This research emphasizes that, in addition to mothers, fathers also require psychological attention and care during the postpartum period.

This indicates that the healthcare system should not focus solely on the mental health issues of mothers after childbirth; fathers may also be affected. Attention to the psychological well-being of fathers impacts not only their health but also the health of the family and the emotional and psychological development of the child. The mental state and supportive role of fathers can serve as a valuable support for the mother and newborn after childbirth.

The results of this study highlight the necessity of psychological interventions and social support for fathers postpartum to prevent long-term issues in this regard. Therefore, routine screening of fathers after childbirth should be conducted, and at-risk individuals should be identified and referred for treatment.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

A. Rouhbakhsh: Designing the study and drafting the manuscript. ShA. Shirkhoda: Study concept and supervision. M. Elyasi: Acquisition of data. H. Fallah Zadeh: Interpretation of data and revising the manuscript. All authors read the final version of manuscript and approved it.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all participants who took part in this study. No artificial intelligence was used for writing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Full-Text: (2 Views)

1. Introduction

Depression is a prevalent mental disorder affecting both mothers and fathers during pregnancy and childbirth (1). Prenatal and postnatal depression resembles other forms of depression, characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest, fatigue, insomnia, and suicidal thoughts (2). While postpartum depression (PPD) in women has been extensively studied (3), emerging evidence suggests that men can also experience depression following childbirth, albeit typically starting later than in women. Fathers may exhibit irritability, emotional withdrawal, risk-taking behaviors or substance use, somatic complaints such as fatigue or headaches, and difficulties in bonding with the infant, rather than overt sadness or tearfulness (4).

Pregnancy can be stressful for both parents; men may develop subtle depression-like symptoms due to emotional bonds, often expressed as isolation, aggression, anxiety, or substance abuse (5). The prevalence of paternal depression in Western countries is estimated to range from 24-25% (6), particularly among first-time fathers, peaking within the first 6 months postpartum due to fatigue and stress from caregiving. These gender-specific symptoms are frequently shaped by male gender role stress, including societal expectations to remain stoic and emotionally restrained, which can lead to feelings of inadequacy and reluctance to seek help (7). Furthermore, paternal depression is closely linked to maternal depression, with studies indicating that 8.4-10% of fathers experience depression during pregnancy, and 6.6-13.6% postpartum (8). This condition can adversely affect child development and parental involvement (9).

Factors contributing to paternal depression include unemployment, poor marital relationships, low socioeconomic status, and stressful life events (10). Despite the significance of paternal mental health, most research has focused on maternal PPD, leaving a gap in understanding fathers’ experiences and help-seeking behaviors. Perceived social support is a crucial factor in mitigating PPD in fathers (11).

Goodman and Garber found that the incidence of paternal depression can vary significantly, with community samples showing rates from 1.2-25.5% and higher rates (24-50%) among men whose partners faced PPD (12). Maternal depression is the strongest predictor of paternal depression during this period, emphasizing the interconnectedness of parental mental health (13). A study highlighted that 11.7% of fathers exhibited depressive symptoms, revealing a positive correlation between perceived stress and PPD, while perceived social support showed a negative correlation (14).

The model predicting PPD based on stress and social support, with vulnerable personality traits as mediators, accounted for 25% of the variance in paternal PPD (15).

The high comorbidity between paternal and maternal PPD can lead to emotional and behavioral issues in children and increased marital conflict (16). Hormonal changes in fathers, including variations in testosterone and cortisol levels, may contribute to the risk of developing PPD (17). A study in Japan reported that 17% of fathers experienced depressive symptoms within the first 3 months postpartum, underscoring the importance of early assessment and support for fathers (18).

In Iran, as fathers assume caregiving roles, safeguarding their mental health is important. Due to paternal depression’s complexity, further research is needed on its prevalence and causes, especially in Yazd’s 2023 context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study involved 270 fathers aged ≥ 18 who referred to 4 healthcare centers in Yazd, Iran for receiving postnatal care of their infants (aged ≤ 2 months) from September 2023-September 2024. Participants and healthcare centers were randomly selected.

2.2. Data collection

To assess participants depression, they were asked to fill the Edinburgh questionnaire (a demographic information questionnaire including education and xx income levels) and a questionnaire regarding the number of children in the family and the prematurity of the newborn. To ensure appropriate distribution of the selected health centers, the city was classified into 3 levels based on existing socioeconomic information: low-income, middle-income, and high-income, with 2 centers randomly chosen from each area.

2.3. Sample size

Considering a 95% confidence level, the prevalence of 26% of this disorder and an estimation error of 5.5%, 245 fathers were needed. The formula for calculating the sample size is as follows:

For greater certainty, 270 participants were included.

The variables examined in this study included the prematurity of the newborn, the sex of the newborn, and number of children, education, income level, and paternal depression.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were fathers aged ≥ 18 who were able to read and understand the questions. The infants were a maximum of 2 months old. Other inclusion criteria were residence in Yazd for access to obtain additional information if needed, willingness to participate in the study, sufficient literacy and cognitive ability to understand the questions and complete the questionnaire, which was determined by measuring the individual’s understanding of the introduction provided by the researcher, absence of significant verbal barriers that would reduce the individual’s understanding of the context and related questions. The exclusion criteria were chronic severe mental disorders or disabilities, and the inability to understand questions among fathers. Visual or hearing impairments that prevent the ability to read or hear the questionnaire questions are also exclusion criteria.

2.5. Edinburgh scale

The Edinburgh PPD scale consists of 10 items. This questionnaire is designed to facilitate the diagnosis of depression from 6 wk postpartum. The score on the Edinburgh scale ranges from zero-30, with a score of 12 or higher considered indicative of PPD.

Questions 1, 2, and 4 are scored from 0-3, while questions 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 are scored from 3-0.

The Cronbach’s alpha for the Edinburgh test is 0.70, and the validity of the Edinburgh test with the Beck scale is 0.44 (19).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.MEDICINE.REC.1402.024). The researcher explained the study process to the participants and collected the necessary information by delivering the questionnaires to individuals after obtaining written informed consent and explaining the confidentiality of the information and the objectives of the research. The information remained confidential and was used solely for research purposes.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

In this study, data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 23.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA (SPSS). Quantitative data were reported using mean and standard deviation, while qualitative data were reported using frequency and percentage. t tests and Chi-square tests were used to analyze quantitative and qualitative variables between 2 groups, and one-way ANOVA tests were used to analyze quantitative variables among more than 2 groups.

3. Results

In this study, 270 fathers aged 35.84 ± 7.18 were examined. Based on education level, 164 individuals (59.6%) had an education below a diploma or had a diploma, and 106 individuals (40.4%) had academic education (bachelor’s degree or higher). Regarding monthly income, > 60% of participants had a moderate income (between 10-20 million), and high-income group were placed after. Among the children, 146 (54.1%) were girls and 124 (45.9%) were boys. Only 14.8% of the children questioned had a history of hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

In the categorization conducted, 81 fathers (30%) were found to have depression. In examining the distribution of depression according to the fathers’ education level, no significant difference was observed between depressed individuals in regards to educational level (p = 0.09).

Considering their level of income, a meaningful negative correlation was observed between depressive scores and average monthly salary (p = 0.002).

Furthermore, among fathers after childbirth, having a baby girl (p = 0.03) was related to higher depression scores significantly, while no similar correlation was observed between number of children (p = 0.1) or history of newborn NICU hospitalization and depression (p = 0.5, Table I, II).

4. Discussion

In this study, 270 fathers were examined. In the present study, 81 fathers (30%) were found to be depressed. This prevalence was less than study conducted by a previous study, which was conducted on 144 fathers; the prevalence of depression among fathers postpartum was reported to be 45.8% (20). Several factors may explain this discrepancy. First, the larger sample size in the present study may have provided a more representative estimate of the general population. Second, differences in sampling methods, timing of assessment, and regional variations in mental health awareness and support systems could have contributed to the lower observed prevalence. Additionally, increased public health attention to maternal mental health in recent years may have indirectly improved paternal coping mechanisms, reducing the severity or recognition of depressive symptoms. However, cultural factors may have played a more significant role in this context. In traditional communities such as Yazd, social norms often discourage emotional expression among men, particularly regarding psychological distress. Feelings of sadness, vulnerability, or anxiety may be perceived as signs of weakness, leading many fathers to suppress or deny such experiences. This cultural stigma not only reduces the likelihood of seeking help but may also limit men’s ability to recognize or articulate their own emotional states. Consequently, the lower prevalence observed in this study may reflect under-reporting rather than an actual reduction in depressive symptoms. In contrast, the prevalence in Western societies has been reported to be between 4% and 25%. In 2 meta-analyses, the prevalence of depression in fathers before childbirth was reported as 8.4% and 10%. In 6 other studies measuring the prevalence of depression in fathers during the postpartum period, it ranged from 6.6%-13.6% (21).

In the prevailing mental conditions during and after pregnancy, more attention has been given to depression in women and mothers than to depression in fathers. This is because the occurrence of depression in fathers can also affect all aspects of family life, including relationships with spouses and children, and fulfilling the role of fatherhood. Because various factors are associated having issues with the wife's family such as a supportive source causing depression, and particularly the economic status of poor and middle-income families as a strong predictor of depression with the onset of depression in fathers and they are different in different societies; it is possible to provide necessary training for early referral by examining risk factors during prenatal care, throughout pregnancy, at the time of childbirth, and postpartum, along with educating about the symptoms of the disease both verbally and in writing.

This study replicated findings on meta-analysis that reported prevalence of PPD, which did not show meaningful difference in terms of number of children or parity (21). In another analysis, it was shown that the monthly income of depressed fathers was significantly lower. 2 previous studies indicated that income level and economic status of the family are related to PPD in fathers (22, 23), which aligns with the results of the present study. Similar results were shown in another study (24).

Our finding that lower income is significantly linked to paternal PPD aligns with international reports. Duan et al. (14) and Fang et al. (22) both noted that financial strain increases the psychological burden on new fathers, especially in cultures that stress the father’s role as the economic provider. This is also true in Iran, where economic pressures and the high cost of raising children can heighten stress during the postpartum period. Addressing economic vulnerability with focused psychosocial support and policy measures could be an important preventive strategy.

The preference for son exists in many cultures in South, East Asia, and Africa. For example, in India, Pakistan, Egypt, and China, there is a preference for male children (24). In Bangladesh, the rate of female fetus abortion is higher, and the association of giving birth to a girl in families that desire a boy has been reported to correlate with PPD (25). The reason for this is the importance of boys in family economics and their roles in rural life and agricultural work. Additionally, boys are considered a source of strength and social security. The results of the present study were consistent with these findings. In Western countries and European cultures, due to the equality of value between genders, this correlation does not exist.

In the present study, several demographic and clinical variables played an important role in shaping paternal depression. Although the level of paternal education was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (p = 0.09), this may suggest that education alone does not offer protection against psychological distress (21). Other mediating factors such as socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs, and social support may be more influential.

Neonatal admission to the NICU also did not show a significant relationship with paternal depression (p = 0.13), despite previous studies identifying NICU admission as emotionally taxing for parents (22). In our sample, family support or prior awareness of the infant’s condition may have helped buffer the emotional impact of hospitalization.

The number of children was significantly associated with paternal depression (p = 0.01), suggesting that increased responsibilities, lower income, and reduced personal time may contribute to emotional strain. This finding is consistent with earlier research highlighting parenting load as a contributing factor (20).

Although the average age of fathers in this study was 35.84 yr, no detailed analysis was conducted regarding the role of age in the onset of depression. Future research may benefit from exploring this variable to better understand how life experience, psychological maturity, and readiness for fatherhood affect mental well-being.

The significant differences in reported prevalence may also be due to variations in tools, their non-standardization, and differing statistical methods in various studies. The prevalence of PPD in mothers remains particularly important, as maternal depression can act as a risk factor for the onset of depression in fathers, which was not examined in this study. Some literature identifies this factor as the strongest predictor of depression in fathers. The cause of its occurrence may be inadequate support from partners (mothers) during this period, leading to feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and lack of control over the situation.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One limitation of this research is that it was conducted in only one city; as studies have shown, although maternal depression has received attention and necessary interventions are being implemented in Iran, paternal depression has not received adequate attention despite its importance for child development and family dynamics. Therefore, further studies on a broader scale and repeated correlation of known related and unrelated variables in this research are essential. It is also suggested that while examining mothers for PPD, questionnaires regarding fathers should also be completed to determine whether, similar to Western literature, maternal depression can be a strong predictor of depression in fathers in Iranian society.

5. Conclusion

The present study examined PPD among fathers and showed that this issue is significantly prevalent not only among mothers, but also among fathers. The findings indicated that fathers, especially in difficult economic and social conditions, and those experiencing fatherhood for the first time, are at greater risk of developing PPD. This research emphasizes that, in addition to mothers, fathers also require psychological attention and care during the postpartum period.

This indicates that the healthcare system should not focus solely on the mental health issues of mothers after childbirth; fathers may also be affected. Attention to the psychological well-being of fathers impacts not only their health but also the health of the family and the emotional and psychological development of the child. The mental state and supportive role of fathers can serve as a valuable support for the mother and newborn after childbirth.

The results of this study highlight the necessity of psychological interventions and social support for fathers postpartum to prevent long-term issues in this regard. Therefore, routine screening of fathers after childbirth should be conducted, and at-risk individuals should be identified and referred for treatment.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

A. Rouhbakhsh: Designing the study and drafting the manuscript. ShA. Shirkhoda: Study concept and supervision. M. Elyasi: Acquisition of data. H. Fallah Zadeh: Interpretation of data and revising the manuscript. All authors read the final version of manuscript and approved it.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all participants who took part in this study. No artificial intelligence was used for writing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Psycology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |