Thu, Jan 29, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 10 (October 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(10): 815-826 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ABZUMS.REC.1404.010

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Baradaran Bagheri R, Hajimaghsoudi L, Mirrahimi S S, Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg A. Association between fibrocystic breast disease and polycystic ovarian syndrome phenotypes: A cross-sectional study. IJRM 2025; 23 (10) :815-826

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3658-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3658-en.html

Ramesh Baradaran Bagheri1

, Leila Hajimaghsoudi2

, Leila Hajimaghsoudi2

, Seyedeh Sanaz Mirrahimi *3

, Seyedeh Sanaz Mirrahimi *3

, Abolfazl Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg4

, Abolfazl Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg4

, Leila Hajimaghsoudi2

, Leila Hajimaghsoudi2

, Seyedeh Sanaz Mirrahimi *3

, Seyedeh Sanaz Mirrahimi *3

, Abolfazl Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg4

, Abolfazl Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg4

1- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Alzahra Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

2- Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

3- Department of Operation Room, Faculty of Paramedicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. ,Mirrahimisanaz@gmail.com; ss.mirrahimi@abzums.ac.ir

4- Department of Pediatrics, Imam Ali Hospital, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

2- Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

3- Department of Operation Room, Faculty of Paramedicine, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. ,

4- Department of Pediatrics, Imam Ali Hospital, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 452 kb]

(474 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (274 Views)

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran (Code: IR.ABZUMS.REC.1404.010). All the authors adhered to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki along with any further revisions, especially regarding the confidentiality of the data.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using independent t test or ANOVA where appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies/percentages and compared using Chi-square tests. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess independent predictors of FBD, adjusting for potential confounders. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Extracted data of 135 women were initially assessed for eligibility during the recruitment phase of the study. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 15 participants were excluded for the following specific reasons: 5 women were excluded due to current pregnancy or lactation, which could influence hormonal and metabolic parameters.

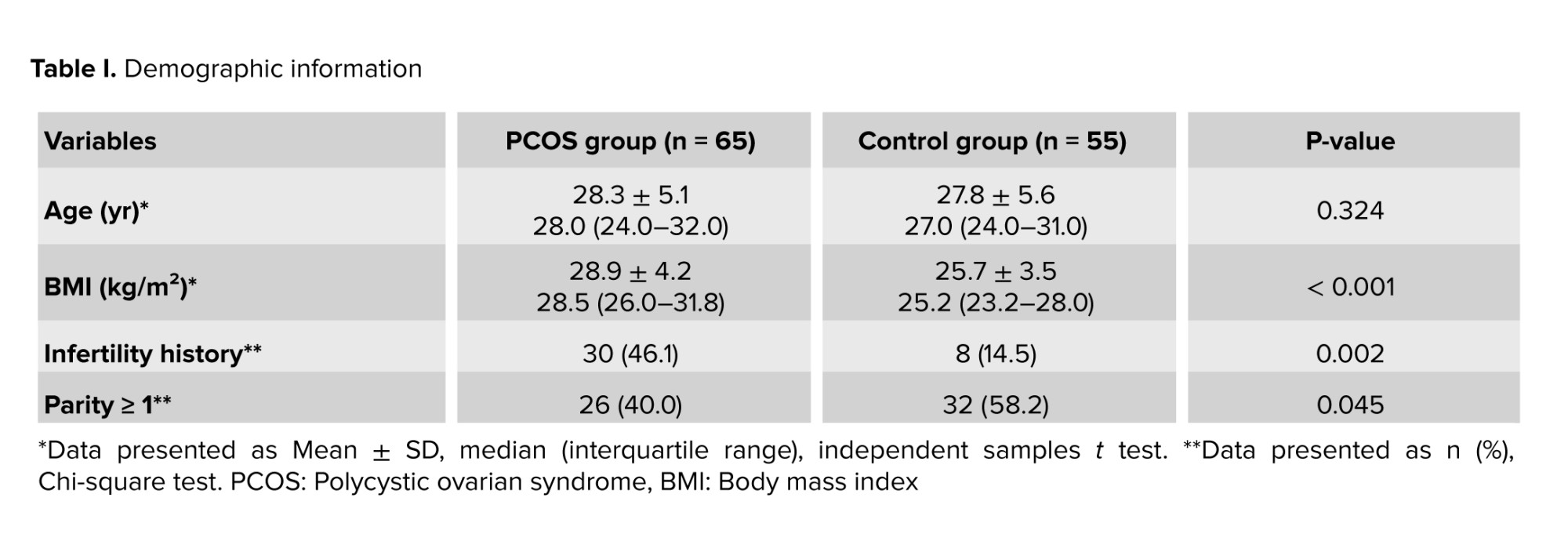

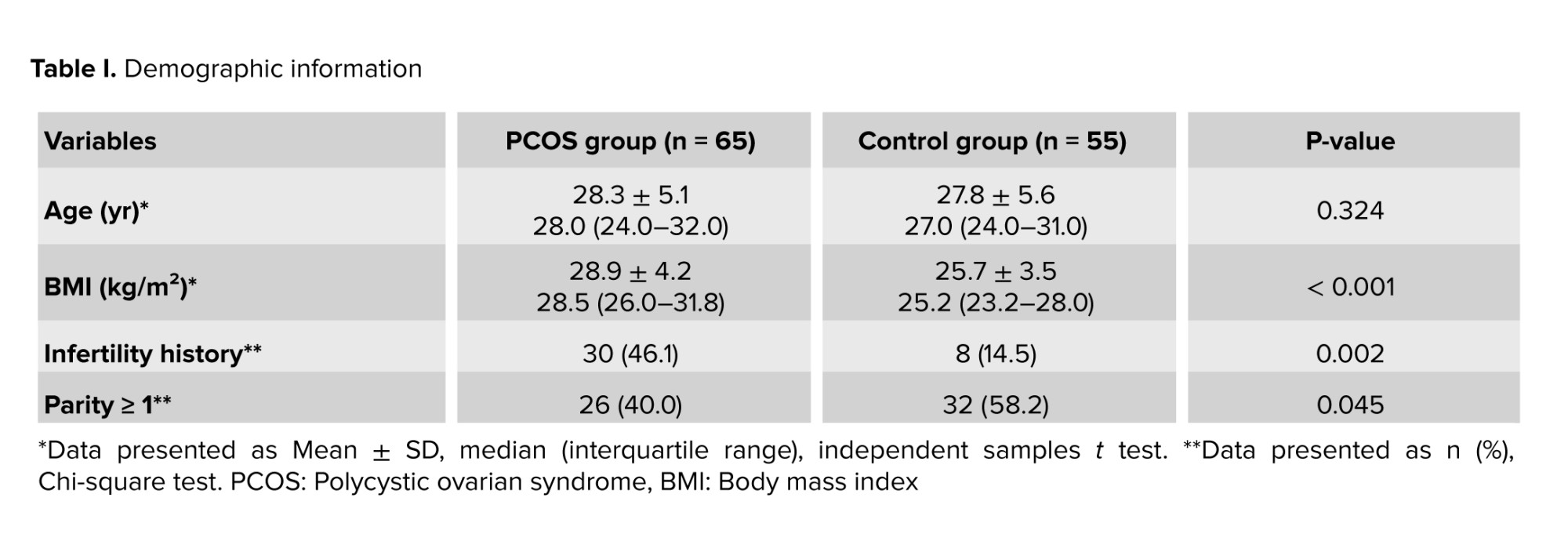

4 women were excluded because they were using oral contraceptive pills at the time of assessment, which could confound hormone levels and imaging results. 6 women were excluded due to the presence of other endocrine disorders such as thyroid dysfunction or hyperprolactinemia. As a result, data of 120 women were finally enrolled in the study, with a mean age of 27.8 ± 5.327 yr. Among them, 65 women were diagnosed with PCOS, and 55 women had FBD. The mean BMI was significantly higher in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (30.4 ± 3.230.4 vs. 26.1 ± 2.926.1; p < 0.001) (Table I).

3.2. Hormonal profile

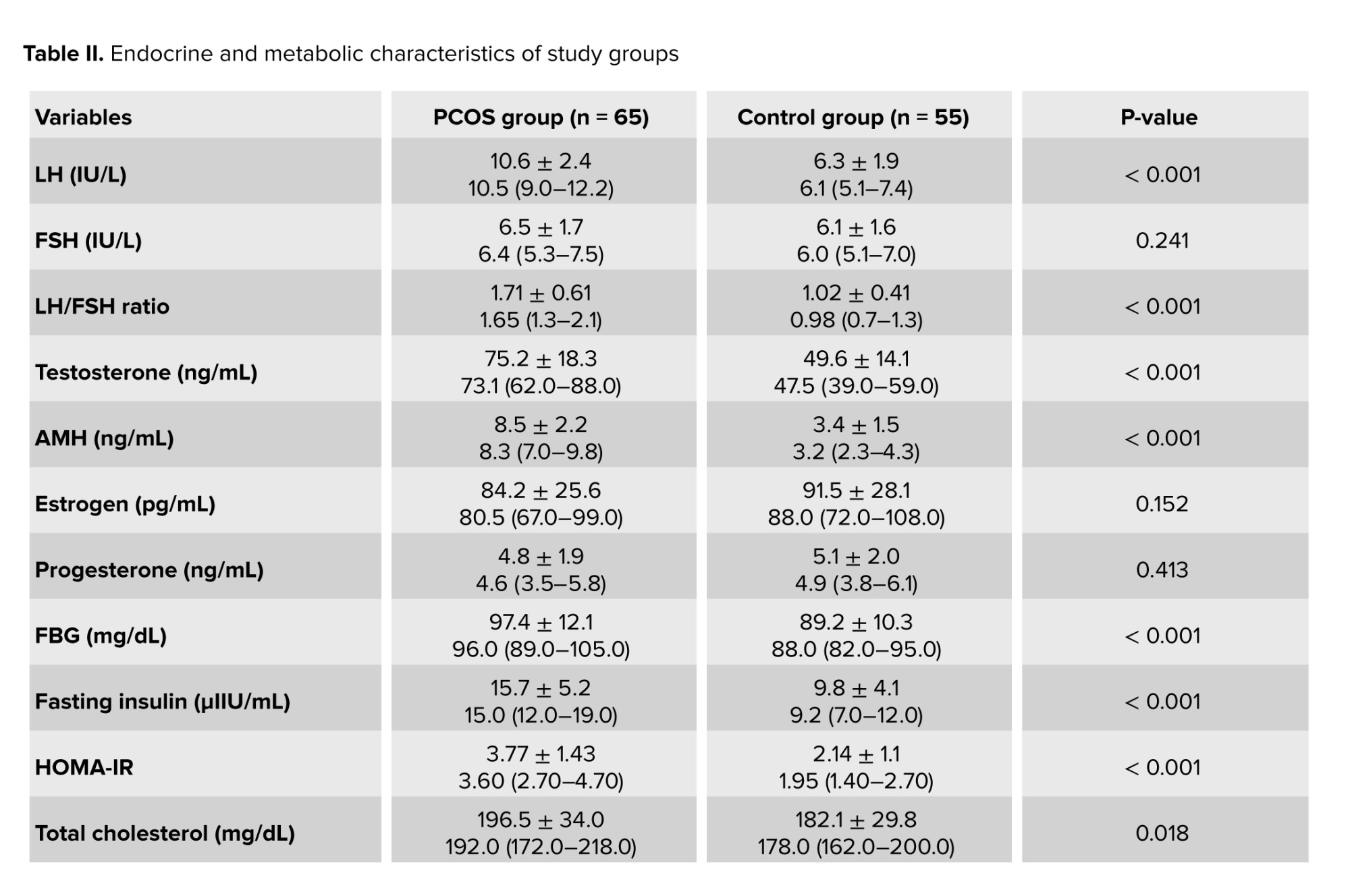

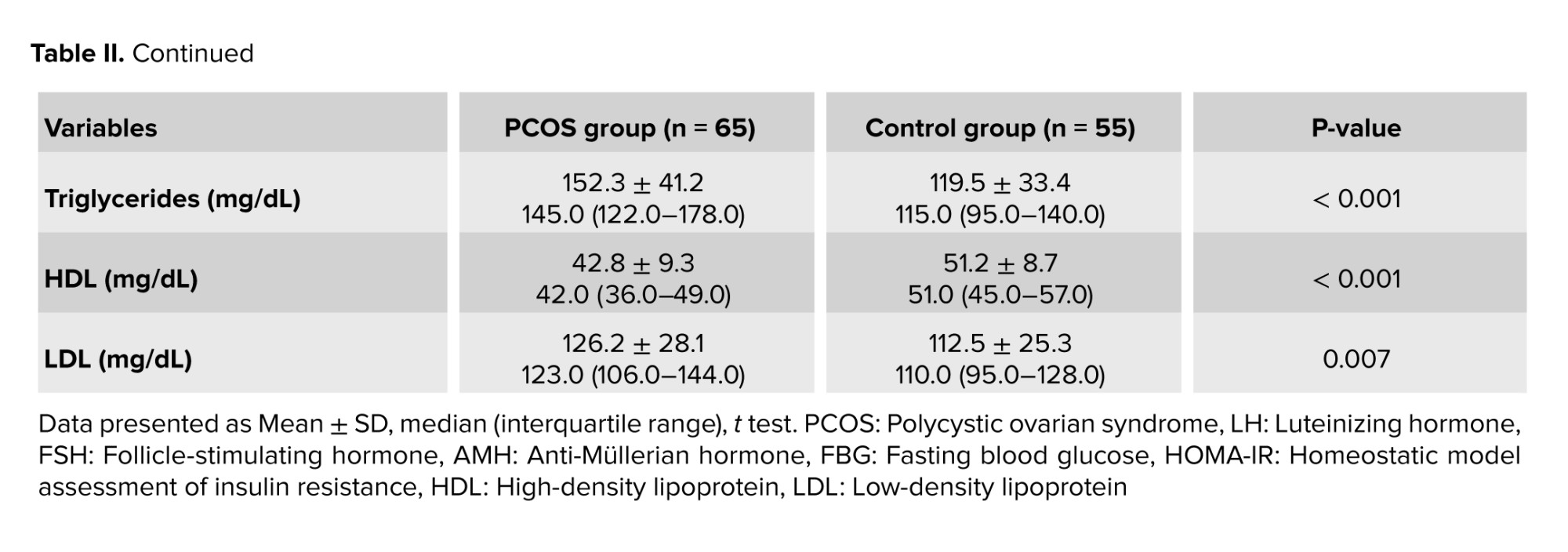

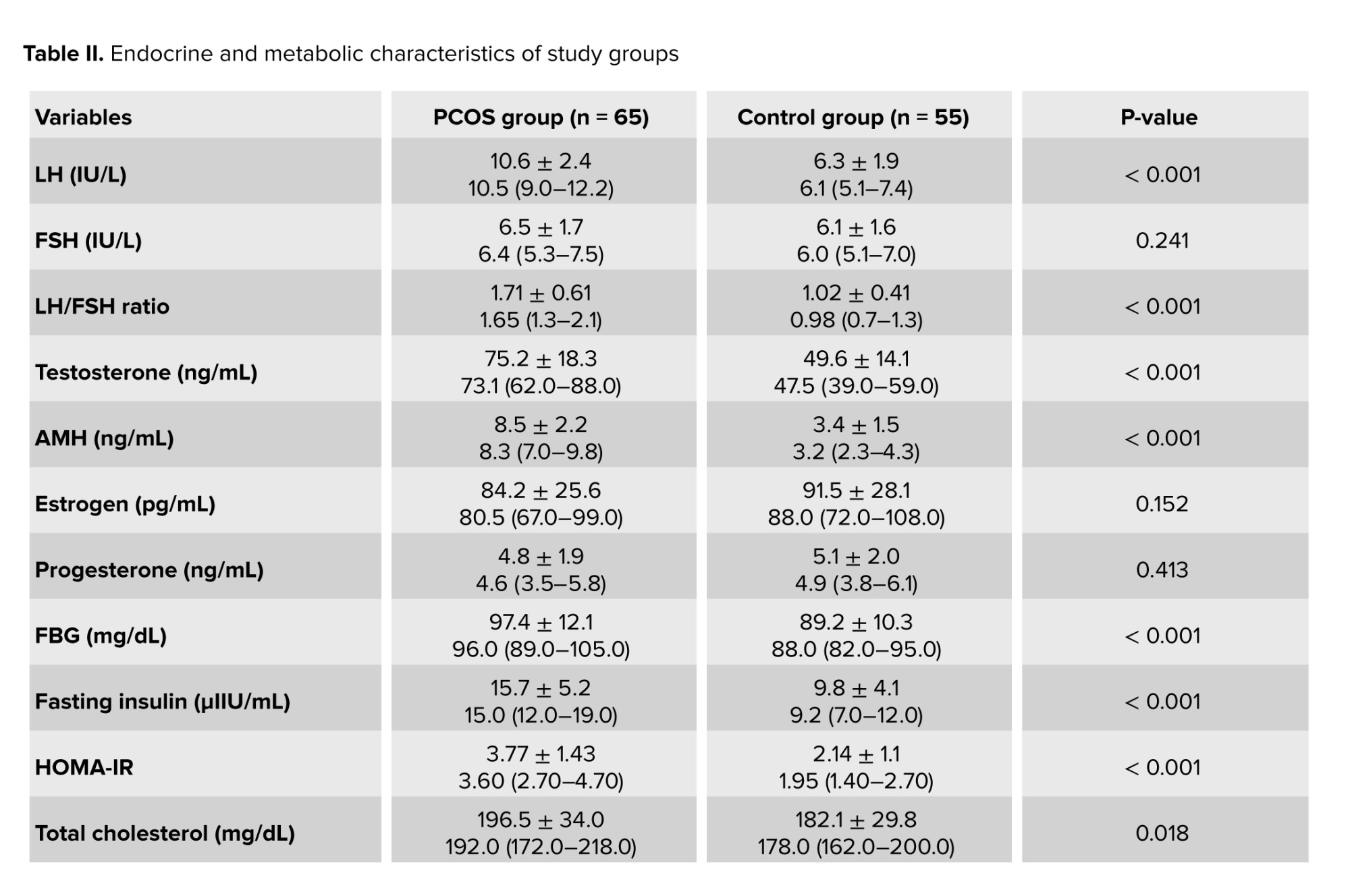

Comparison of hormonal parameters between the 2 groups showed significantly higher levels of LH and AMH in the PCOS group. The LH/FSH ratio was also significantly elevated in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (Table II).

3.3. Prevalence of FBD

Among the 65 women diagnosed with PCOS, 35 individuals (53.8%) were found to have FBD, whereas in the control group, only 18 out of 55 (32.7%) had FBD. Statistical analysis using the chi-square test demonstrated a significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.003), indicating a positive association between PCOS and an increased risk of FBD.

3.4. Phenotype-based analysis

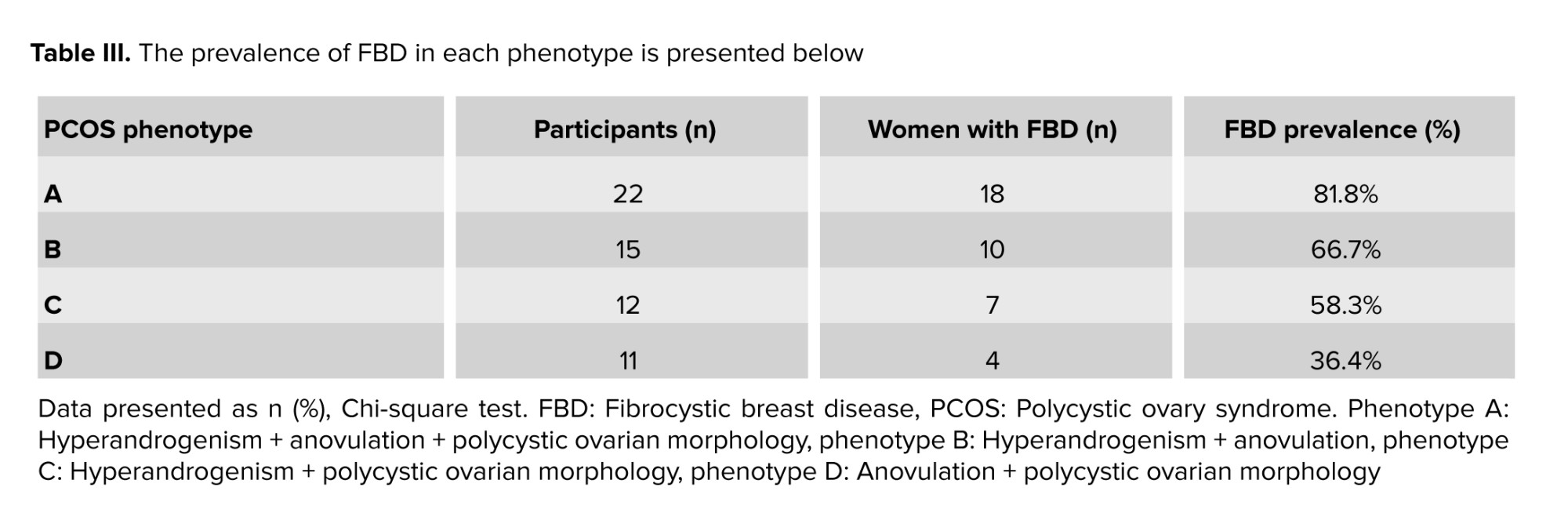

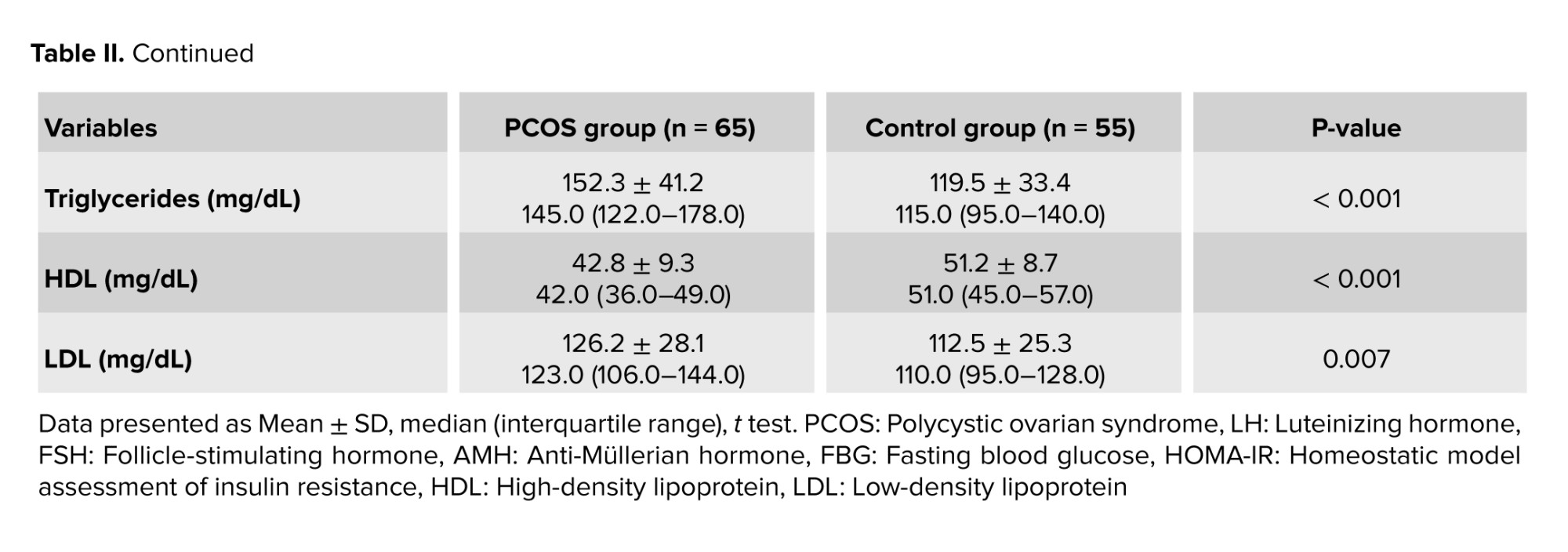

The PCOS group was further classified into 4 phenotypes according to the Rotterdam criteria. The prevalence of FBD within each phenotype was as follows: phenotype A (hyperandrogenism + anovulation + polycystic ovaries; n = 22) had the highest prevalence at 81.8% (18/22), followed by phenotype B (hyperandrogenism + anovulation; n = 15) at 66.7% (10/15), phenotype C (hyperandrogenism + polycystic ovaries; n = 12) at 58.3% (7/12), and phenotype D (anovulation + polycystic ovaries; n = 11) at 36.4% (4/11). Chi-square analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in FBD prevalence among the PCOS phenotypes (p = 0.01), indicating that certain phenotypes may confer a higher risk for developing FBD.

As shown, the highest prevalence of FBD was observed in phenotype A, with 81.8% of individuals affected. Chi-square analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in FBD prevalence among the PCOS phenotypes (p = 0.01), indicating that certain phenotypes may confer a higher risk for developing FBD (Table III).

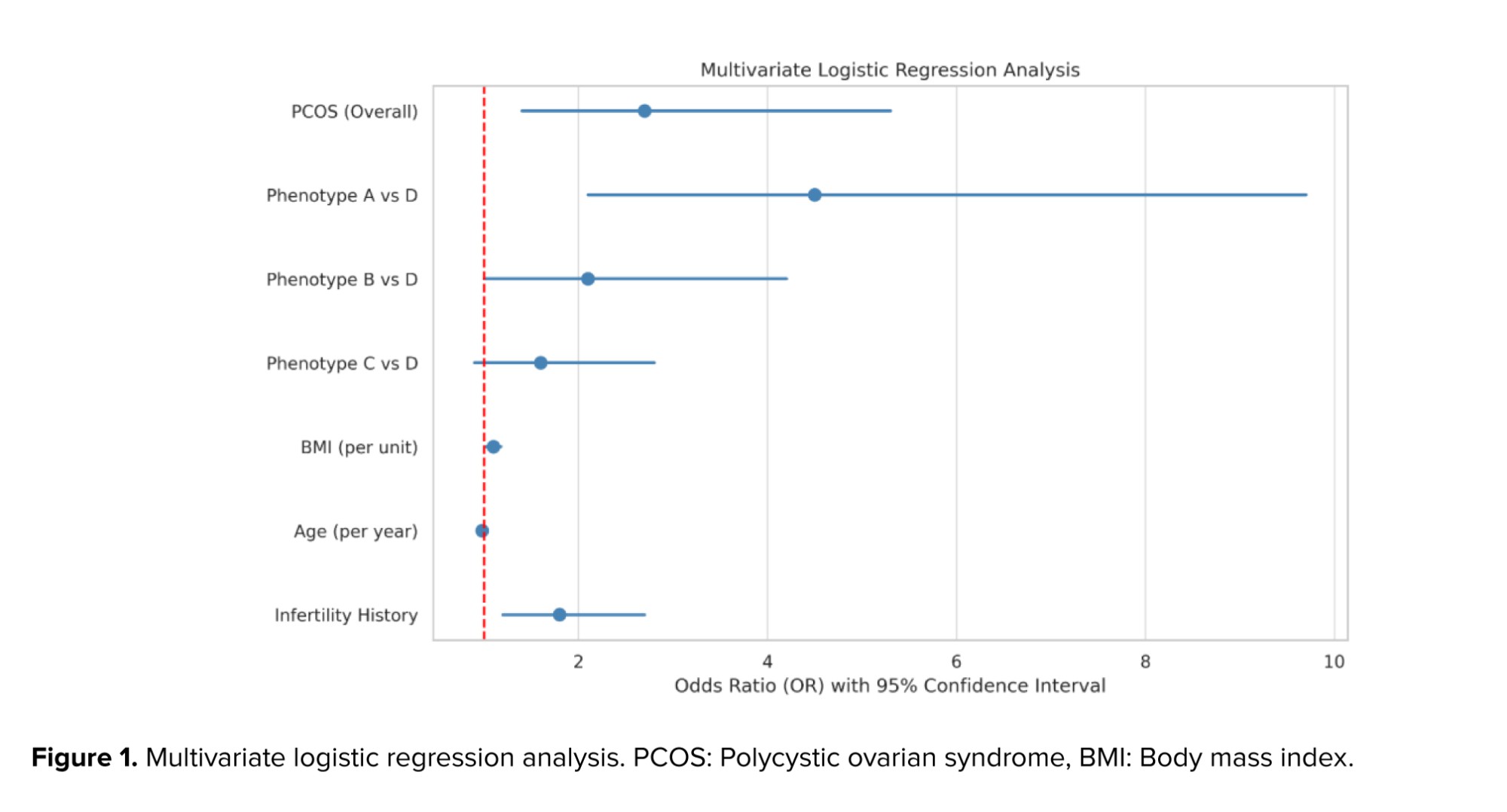

3.5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

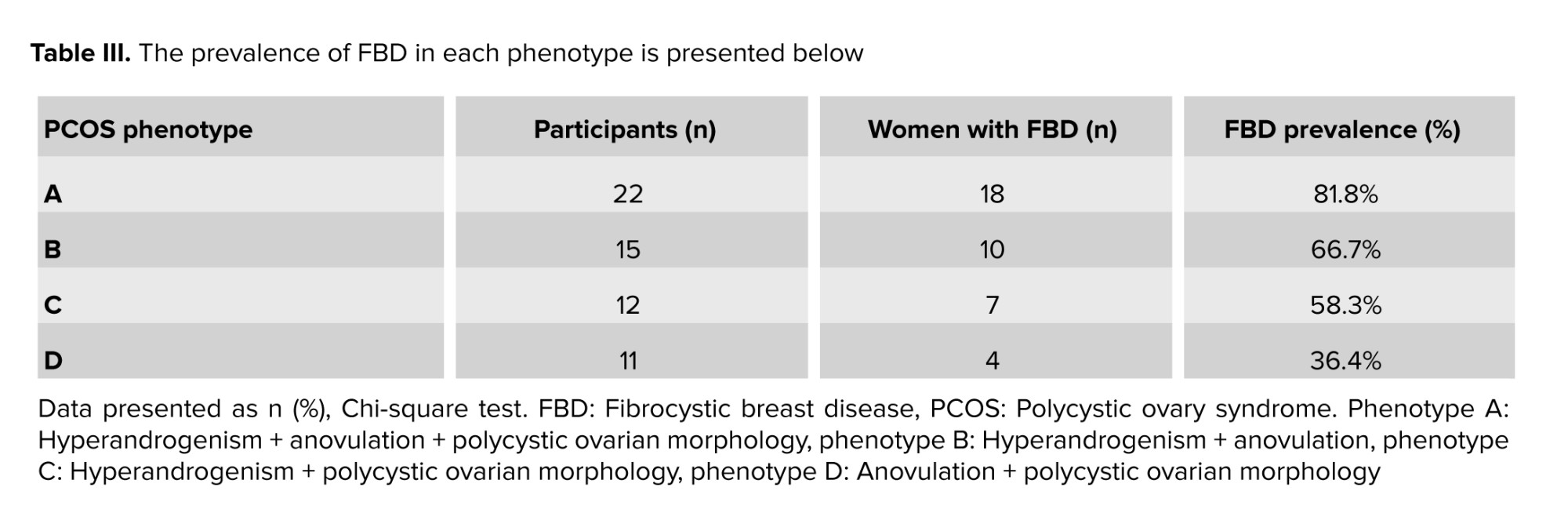

To identify independent predictors of FBD, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted. The presence of PCOS was independently associated with increased odds of FBD (odds ratio [OR] = 3.12; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.51-6.45; p = 0.002). Furthermore, phenotype A exhibited a significantly higher risk of FBD compared to phenotype D (OR = 4.9; p = 0.001) (Figure 1).

3.6. Metabolic results

Evaluation of metabolic parameters between the PCOS and FBD groups revealed statistically significant differences in several indices. Women with PCOS had higher FBG, insulin levels, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, indicating a greater degree of insulin resistance. Additionally, the lipid profile analysis showed elevated triglyceride and LDL levels and lower HDL levels in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (Table II).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of FBD among women with PCOS compared to the control group (58.3% vs. 30%, p = 0.003). Among PCOS phenotypes, phenotype A -characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM- showed the highest FBD prevalence (81.8%). Logistic regression analysis confirmed that the presence of PCOS increased the odds of FBD more than threefold (OR = 3.12; 95% CI: 1.51-6.45). Additionally, women with PCOS exhibited significant hormonal imbalances (elevated LH, AMH, and testosterone) and metabolic disturbances (higher insulin resistance and dyslipidemia), which may contribute to breast tissue alterations.

In addition to phenotype-based associations, our study also evaluated individual hormonal variables. Levels of AMH, LH, and testosterone were significantly elevated in the PCOS group compared to controls, confirming the characteristic hormonal imbalance of PCOS. Elevated AMH reflects ovarian follicular excess and dysfunction and may indirectly contribute to breast tissue changes. Similarly, the increased LH/FSH ratio was consistent with prior findings in PCOS populations (15, 16). In contrast, estrogen and progesterone levels did not significantly differ between groups, which aligns with earlier reports showing relatively preserved gonadal steroid production in PCOS. Taken together, these hormonal patterns -particularly high AMH and LH/FSH ratio combined with hyperandrogenism- along with metabolic abnormalities may provide a plausible mechanistic pathway linking PCOS to the increased prevalence of FBD.

These findings suggest a strong association between PCOS -especially more severe phenotypes- and an increased risk of FBD. The results align with some previous reports while contrasting with others, highlighting the need for phenotype-based interpretation and further investigation into hormonal interactions affecting breast tissue.

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age and is associated with a spectrum of hormonal, metabolic, and reproductive abnormalities. The current study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of FBD among women with PCOS compared to those without the syndrome. This finding contrasts with some earlier reports that failed to establish a clear association between PCOS and benign breast conditions (17, 18).

In this study, the overall prevalence of FBD in the PCOS group reached 58.3%, with an especially high rate of 81.8% observed among women with phenotype A (characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM). This finding aligns with a previous study that also reported significant differences in FBD prevalence among different PCOS phenotypes. However, in contrast to our results, the study suggested that hyperandrogenism -particularly elevated free testosterone- might exert a protective effect against FBD (19). This contrasts with our findings, which demonstrated a higher prevalence of FBD in phenotypes with elevated androgen levels. Such discrepancies may stem from differences in phenotypic definitions, population characteristics, or FBD diagnostic methods across studies.

A recent systematic review concluded that no clear link was observed between PCOS and BBD (1). However, the differences in study design (cross-sectional vs. systematic review), sample selection methods, and lack of phenotypic analysis in that review may explain the divergent results. Notably, the present study’s stratification by PCOS phenotypes is a methodological strength that allows for more nuanced interpretation (20).

A recent investigation conducted among postmenopausal women reported that a history of PCOS in the premenopausal period increased the risk of developing fibrocystic changes after menopause. This is consistent with our findings in a reproductive-age population and may reflect the long-term effects of hormonal disturbances in PCOS on breast tissue architecture (21).

Earlier research has similarly found a higher prevalence of BBD among women with polycystic ovaries (PAO) and PCOS, as confirmed by pelvic ultrasound and mammography. This provides further support for a potential relationship between PCOS and breast tissue alterations (1).

Conversely, a comprehensive review exploring long-term outcomes of PCOS, including breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers, highlighted a complex and often inconsistent relationship (22, 23). While PCOS was clearly associated with endometrial cancer, the evidence for breast cancer and FBD was inconclusive. This underscores the need for well-designed studies with detailed phenotypic characterization and control for potential confounding factors (24).

Overall, the results of this study support the hypothesis that hormonal and metabolic disturbances associated with PCOS -particularly in more severe phenotypes- may contribute to fibrocystic changes in breast tissue (23, 25). However, discrepancies among studies emphasize the importance of phenotype-based analyses and consideration of population and methodological differences. Further prospective, large-scale investigations are warranted to better understand the underlying mechanisms linking PCOS with benign breast pathologies.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights a noteworthy link between PCOS and FBD, particularly among women with the more hormonally and metabolically severe phenotypes of PCOS. The significantly higher prevalence of FBD in phenotype A suggests that the interplay of hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM may influence the development of benign breast changes. These findings point to a shared hormonal and metabolic pathophysiology underlying both conditions. Given the widespread occurrence of PCOS among women of reproductive age and its broad spectrum of systemic effects, the association with FBD adds an important dimension to the clinical implications of the disorder. This reinforces the need for routine breast health screening in women with PCOS, especially those exhibiting complex phenotypic features. In a broader context, the results of this study underscore the interconnectedness of endocrine and reproductive health in women. Recognizing these associations not only helps clinicians deliver more comprehensive care but also contributes to early detection and prevention strategies. Future longitudinal and mechanistic studies are warranted to explore the causal pathways linking PCOS and BBDs, ultimately improving women's health outcomes across the lifespan.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

R. Baradaran Bagheri and S.S. Mirrahimi designed the study and conducted the research. L. Hajimaghsoudi and R. Baradaran Bagheri are supervisor and write the draft of manuscript. A. Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg, R. Baradaran Bagheri monitored, evaluated, and analyzed the results of the study. R. Baradaran Bagheri reviewed the article. All authors approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article sincerely thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran and Clinical Research Development Unit of Tabriz Valiasr hospital, Tabriz, Iran for their unwavering support and assistance in this research. We also extend our gratitude to the developers of the DeepSeek AI tool, which was used to enhance the quality of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Full-Text: (3 Views)

1. Introduction

Fibrocystic breast disease (FBD) is one of the most common benign breast disorders in women, characterized by abnormal structural and functional changes in breast tissue. This condition may present with symptoms such as pain, tenderness, and the formation of fibrocystic lumps. Although benign, it often leads to anxiety and necessitates further diagnostic evaluations (1).

At the same time, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is recognized as one of the most prevalent endocrine disorders among women of reproductive age, manifesting with features such as irregular menstruation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) (2, 3). PCOS is associated with complications such as infertility, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, depression, and an increased risk of endometrial cancer (4, 5). According to previous studies, the prevalence of PCOS varies between 5% and 15%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. The internationally accepted diagnostic criteria include the presence of at least 2 of the following 3 features: ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical), and PCOM on ultrasound (6, 7). In contrast, breast tissue development and differentiation are highly influenced by hormonal changes.

2 studies have shown that treatments involving estrogen, progestins, or anti-estrogens can play a role in the development or prevention of benign breast lesions (8, 9). For instance, the large-scale women's health initiative study reported a 74% increase in the risk of benign breast disease (BBD) with combined estrogen-progesterone therapy, while the use of anti-estrogens was associated with a reduced risk (9). Benign breast changes, especially during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, may appear as hyperplasia, sclerosing adenosis, or cysts (10). Some of these changes may also be linked to an increased risk of breast cancer, particularly when the proliferative index (Ki-67) exceeds 2% (11, 12). Since both PCOS and FBD are associated with hormonal disturbances, a potential pathophysiological relationship between them has been suggested. However, to date, this association has not been comprehensively examined, and further studies are needed to clarify their interrelation (1, 13).

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the critical role of hormones in their pathophysiology, and the clinical concerns surrounding them, investigating the association between PCOS and FBD may contribute significantly to identifying shared risk factors, improving screening and treatment approaches, and ultimately enhancing women's health. The present study was designed to explore this association and analyze the prevalence of FBD in women with different PCOS phenotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

In this cross-sectional study, data of 120 women diagnosed with either FBD or PCOS who were referred to Kamali hospital affiliated with Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran, from March 2024-March 2025 were extracted through medical records and hormonal laboratory tests. Data were collected using a researcher-designed checklist, which included demographic information (age, body mass index [BMI], menstrual history, infertility, number of deliveries) and laboratory hormonal results (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], luteinizing hormone [LH], testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, and anti-Müllerian hormone [AMH]). All hormone measurements were performed in a single certified laboratory using standardized immunoassay techniques to ensure consistency across participants.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Women aged between 17-36 yr were included if they met one of the following diagnostic categories. Participants in the PCOS group were diagnosed according to the Rotterdam 2003 criteria, which require the presence of at least 2 of the following 3 features: clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism (e.g., elevated serum testosterone or clinical signs such as acne, or alopecia, or a Ferriman-Gallwey score, indicating hirsutism), ovulatory dysfunction (manifested as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea), and PCOM defined as the presence of ≥ 20 follicles per ovary and/or an ovarian volume exceeding > 10 mL on ultrasonography.

Participants in the control group/FBD group: were diagnosed based on breast ultrasonography and where applicable, mammography, with findings reported using the standard breast imaging-reporting and data system lexicon and confirmed by a qualified surgeon or gynecologist. All participants had to be without current use of any formulation of oral contraceptives (14).

Women were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating at the time of enrollment, using oral contraceptives, or had been diagnosed with other significant endocrine disorders such as thyroid dysfunction or hyperprolactinemia.

2.3. Study groups

Participants were divided into 2 main groups. The PCOS group (n = 65) comprised women were diagnosed with PCOS according to the specified inclusion criteria. Within this group, 35 women (58.3%) also presented with FBD, while the remaining 30 women (46.2%) had PCOS without FBD. The control group (n = 55) included women who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for PCOS and served as the control population. Although some may have been referred for general medical reasons, but did not meet PCOS diagnostic criteria. Among them, 18 women (30%) were diagnosed with FBD, whereas 37 women (70%) had neither PCOS nor FBD.

2.4. Data sources and measurement methods

Data for all participants (both the PCOS and control groups) were retrospectively extracted from a single, unified electronic medical records (EMR) system of the Kamali hospital, Karaj, Iran. This ensured that the source of data and the methods of assessment were identical for both groups, guaranteeing comparability. The specific details for each variable of interest are as follows:

2.4.1. Demographic and clinical variables

Data were obtained from patient intake forms and physician notes documented within the EMR system. Key variables including age, BMI (calculated from recorded height and weight), menstrual history (based on patient-reported cycle regularity), history of infertility (as diagnosis by a physician), and number of deliveries (parity) were extracted directly from standardized medical history documentation. To ensure comparability, all patients referred to the clinic were assessed using uniform data collection forms and EMR templates, thereby maintaining consistency in evaluation procedures.

2.4.2. PCOS diagnosis and phenotyping

The diagnosis of PCOS and the assignment to phenotypes (A, B, C, D) were determined by the treating endocrinologist/gynecologist based on the Rotterdam criteria. This assessment was based on clinical notes, laboratory reports, and ultrasonography findings within the EMR. Clinical hyperandrogenism was identified through physical examination (e.g., Ferriman-Gallwey score, presence of acne/alopecia). Biochemical hyperandrogenism was confirmed by measing serum testosterone levels. Ovulatory dysfunction was assessed based on the patient-reported history of oligo-/amenorrhea.

PCOM was evaluated via transvaginal or abdominal ultrasonography performed by a certified radiologist, defined as the presence of ≥ 20 follicles per ovary and/or an ovarian volume > 10 mL. To ensure comparability. The same Rotterdam diagnostic criteria and clinical assessment standards were applied to all potential PCOS women. The control group was defined by the absence of these diagnostic criteria.

2.4.3. FBD diagnosis

The diagnosis of FBD was confirmed through a combination of radiology reports (ultrasonography and/or mammography) and confirming clinical diagnosis in the EMR. Imaging was performed by a breast radiologist using the standard breast imaging-reporting and data system lexicon (e.g., cysts, fibroglandular tissue, benign findings). The final clinical diagnosis was made by a surgeon or gynecologist. To ensure comparability all women referred for breast imaging were evaluated by the same radiological equipment, protocols, and diagnostic criteria, regardless of their PCOS status.

2.4.4. Hormonal and biochemical variables

All laboratory data were obtained from a single, certified central laboratory within the hospital. Blood samples were collected during the early follicular phase (days 2-5) for cycling women, or following a progesterone-induced withdrawal bleed in amenorrheic women, to ensure hormonal consistency. Hormonal analyses including LH, FSH, testosterone, estrogen, progesterone were performed using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics).

AMH level were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. To maintain methodological consistency and eliminate inter-assay and inter-laboratory variability, all laboratory measurements for both PCOS and control groups were performed in the same laboratory, using identical assay kits, analytical techniques, and equipment, and during the same time period. This approach ensured direct comparability of all laboratory results across study participants.

2.4.5. Metabolic variables

All metabolic assessments were conducted using laboratory reports from the same central laboratory. Blood samples for fasting blood glucose (FBG), insulin, and lipid profiles (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL) were collected after a 12-hr overnight fast. FBG and lipid profile were analyzed using enzymatic colorimetric methods, while fasting insulin levels were measured via electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. HOMA-IR calculated as (fasting insulin [μIU/mL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL])/405. To ensure comparability all metabolic parameters for all subjects were measured using identical methods in the same laboratory, ensuring complete comparability between the groups.

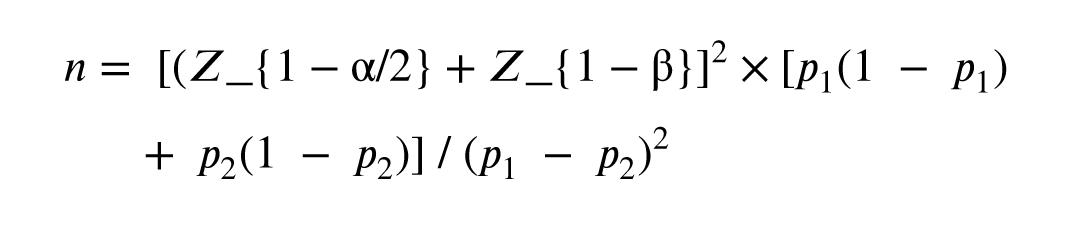

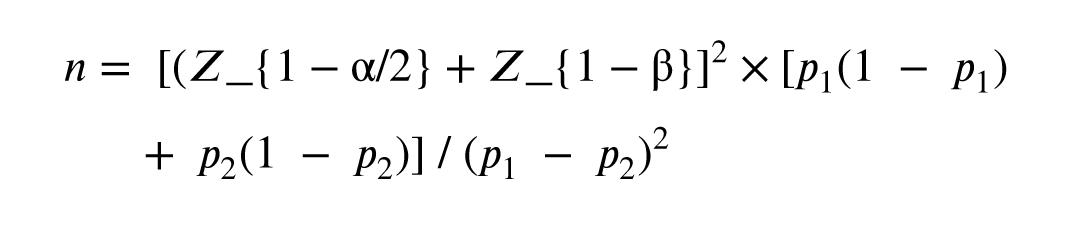

2.5. Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the formula for comparing 2 proportions, assuming a prevalence of FBD of 50% in PCOS and 25% in controls, with α = 0.05 and power = 80%. The minimum required sample was 93 (53 PCOS, 40 controls). To account for dropouts, the final sample was increased to 120.

Where:

Fibrocystic breast disease (FBD) is one of the most common benign breast disorders in women, characterized by abnormal structural and functional changes in breast tissue. This condition may present with symptoms such as pain, tenderness, and the formation of fibrocystic lumps. Although benign, it often leads to anxiety and necessitates further diagnostic evaluations (1).

At the same time, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is recognized as one of the most prevalent endocrine disorders among women of reproductive age, manifesting with features such as irregular menstruation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) (2, 3). PCOS is associated with complications such as infertility, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, depression, and an increased risk of endometrial cancer (4, 5). According to previous studies, the prevalence of PCOS varies between 5% and 15%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. The internationally accepted diagnostic criteria include the presence of at least 2 of the following 3 features: ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical), and PCOM on ultrasound (6, 7). In contrast, breast tissue development and differentiation are highly influenced by hormonal changes.

2 studies have shown that treatments involving estrogen, progestins, or anti-estrogens can play a role in the development or prevention of benign breast lesions (8, 9). For instance, the large-scale women's health initiative study reported a 74% increase in the risk of benign breast disease (BBD) with combined estrogen-progesterone therapy, while the use of anti-estrogens was associated with a reduced risk (9). Benign breast changes, especially during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, may appear as hyperplasia, sclerosing adenosis, or cysts (10). Some of these changes may also be linked to an increased risk of breast cancer, particularly when the proliferative index (Ki-67) exceeds 2% (11, 12). Since both PCOS and FBD are associated with hormonal disturbances, a potential pathophysiological relationship between them has been suggested. However, to date, this association has not been comprehensively examined, and further studies are needed to clarify their interrelation (1, 13).

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the critical role of hormones in their pathophysiology, and the clinical concerns surrounding them, investigating the association between PCOS and FBD may contribute significantly to identifying shared risk factors, improving screening and treatment approaches, and ultimately enhancing women's health. The present study was designed to explore this association and analyze the prevalence of FBD in women with different PCOS phenotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

In this cross-sectional study, data of 120 women diagnosed with either FBD or PCOS who were referred to Kamali hospital affiliated with Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran, from March 2024-March 2025 were extracted through medical records and hormonal laboratory tests. Data were collected using a researcher-designed checklist, which included demographic information (age, body mass index [BMI], menstrual history, infertility, number of deliveries) and laboratory hormonal results (follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], luteinizing hormone [LH], testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, and anti-Müllerian hormone [AMH]). All hormone measurements were performed in a single certified laboratory using standardized immunoassay techniques to ensure consistency across participants.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Women aged between 17-36 yr were included if they met one of the following diagnostic categories. Participants in the PCOS group were diagnosed according to the Rotterdam 2003 criteria, which require the presence of at least 2 of the following 3 features: clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism (e.g., elevated serum testosterone or clinical signs such as acne, or alopecia, or a Ferriman-Gallwey score, indicating hirsutism), ovulatory dysfunction (manifested as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea), and PCOM defined as the presence of ≥ 20 follicles per ovary and/or an ovarian volume exceeding > 10 mL on ultrasonography.

Participants in the control group/FBD group: were diagnosed based on breast ultrasonography and where applicable, mammography, with findings reported using the standard breast imaging-reporting and data system lexicon and confirmed by a qualified surgeon or gynecologist. All participants had to be without current use of any formulation of oral contraceptives (14).

Women were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating at the time of enrollment, using oral contraceptives, or had been diagnosed with other significant endocrine disorders such as thyroid dysfunction or hyperprolactinemia.

2.3. Study groups

Participants were divided into 2 main groups. The PCOS group (n = 65) comprised women were diagnosed with PCOS according to the specified inclusion criteria. Within this group, 35 women (58.3%) also presented with FBD, while the remaining 30 women (46.2%) had PCOS without FBD. The control group (n = 55) included women who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for PCOS and served as the control population. Although some may have been referred for general medical reasons, but did not meet PCOS diagnostic criteria. Among them, 18 women (30%) were diagnosed with FBD, whereas 37 women (70%) had neither PCOS nor FBD.

2.4. Data sources and measurement methods

Data for all participants (both the PCOS and control groups) were retrospectively extracted from a single, unified electronic medical records (EMR) system of the Kamali hospital, Karaj, Iran. This ensured that the source of data and the methods of assessment were identical for both groups, guaranteeing comparability. The specific details for each variable of interest are as follows:

2.4.1. Demographic and clinical variables

Data were obtained from patient intake forms and physician notes documented within the EMR system. Key variables including age, BMI (calculated from recorded height and weight), menstrual history (based on patient-reported cycle regularity), history of infertility (as diagnosis by a physician), and number of deliveries (parity) were extracted directly from standardized medical history documentation. To ensure comparability, all patients referred to the clinic were assessed using uniform data collection forms and EMR templates, thereby maintaining consistency in evaluation procedures.

2.4.2. PCOS diagnosis and phenotyping

The diagnosis of PCOS and the assignment to phenotypes (A, B, C, D) were determined by the treating endocrinologist/gynecologist based on the Rotterdam criteria. This assessment was based on clinical notes, laboratory reports, and ultrasonography findings within the EMR. Clinical hyperandrogenism was identified through physical examination (e.g., Ferriman-Gallwey score, presence of acne/alopecia). Biochemical hyperandrogenism was confirmed by measing serum testosterone levels. Ovulatory dysfunction was assessed based on the patient-reported history of oligo-/amenorrhea.

PCOM was evaluated via transvaginal or abdominal ultrasonography performed by a certified radiologist, defined as the presence of ≥ 20 follicles per ovary and/or an ovarian volume > 10 mL. To ensure comparability. The same Rotterdam diagnostic criteria and clinical assessment standards were applied to all potential PCOS women. The control group was defined by the absence of these diagnostic criteria.

2.4.3. FBD diagnosis

The diagnosis of FBD was confirmed through a combination of radiology reports (ultrasonography and/or mammography) and confirming clinical diagnosis in the EMR. Imaging was performed by a breast radiologist using the standard breast imaging-reporting and data system lexicon (e.g., cysts, fibroglandular tissue, benign findings). The final clinical diagnosis was made by a surgeon or gynecologist. To ensure comparability all women referred for breast imaging were evaluated by the same radiological equipment, protocols, and diagnostic criteria, regardless of their PCOS status.

2.4.4. Hormonal and biochemical variables

All laboratory data were obtained from a single, certified central laboratory within the hospital. Blood samples were collected during the early follicular phase (days 2-5) for cycling women, or following a progesterone-induced withdrawal bleed in amenorrheic women, to ensure hormonal consistency. Hormonal analyses including LH, FSH, testosterone, estrogen, progesterone were performed using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics).

AMH level were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. To maintain methodological consistency and eliminate inter-assay and inter-laboratory variability, all laboratory measurements for both PCOS and control groups were performed in the same laboratory, using identical assay kits, analytical techniques, and equipment, and during the same time period. This approach ensured direct comparability of all laboratory results across study participants.

2.4.5. Metabolic variables

All metabolic assessments were conducted using laboratory reports from the same central laboratory. Blood samples for fasting blood glucose (FBG), insulin, and lipid profiles (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL) were collected after a 12-hr overnight fast. FBG and lipid profile were analyzed using enzymatic colorimetric methods, while fasting insulin levels were measured via electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. HOMA-IR calculated as (fasting insulin [μIU/mL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL])/405. To ensure comparability all metabolic parameters for all subjects were measured using identical methods in the same laboratory, ensuring complete comparability between the groups.

2.5. Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the formula for comparing 2 proportions, assuming a prevalence of FBD of 50% in PCOS and 25% in controls, with α = 0.05 and power = 80%. The minimum required sample was 93 (53 PCOS, 40 controls). To account for dropouts, the final sample was increased to 120.

Where:

- n: required sample size per group

- p₁: estimated proportion in group 1 (e.g., FBD prevalence in PCOS)

- p₂: estimated proportion in group 2 (e.g., FBD prevalence in controls)

- Z_{1-α/2}: Z-score for the desired confidence level (e.g., 1.96 for 95%)

- Z_{1-β}: Z-score for desired power (e.g., 0.84 for 80%)

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran (Code: IR.ABZUMS.REC.1404.010). All the authors adhered to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki along with any further revisions, especially regarding the confidentiality of the data.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using independent t test or ANOVA where appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies/percentages and compared using Chi-square tests. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess independent predictors of FBD, adjusting for potential confounders. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Extracted data of 135 women were initially assessed for eligibility during the recruitment phase of the study. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 15 participants were excluded for the following specific reasons: 5 women were excluded due to current pregnancy or lactation, which could influence hormonal and metabolic parameters.

4 women were excluded because they were using oral contraceptive pills at the time of assessment, which could confound hormone levels and imaging results. 6 women were excluded due to the presence of other endocrine disorders such as thyroid dysfunction or hyperprolactinemia. As a result, data of 120 women were finally enrolled in the study, with a mean age of 27.8 ± 5.327 yr. Among them, 65 women were diagnosed with PCOS, and 55 women had FBD. The mean BMI was significantly higher in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (30.4 ± 3.230.4 vs. 26.1 ± 2.926.1; p < 0.001) (Table I).

3.2. Hormonal profile

Comparison of hormonal parameters between the 2 groups showed significantly higher levels of LH and AMH in the PCOS group. The LH/FSH ratio was also significantly elevated in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (Table II).

3.3. Prevalence of FBD

Among the 65 women diagnosed with PCOS, 35 individuals (53.8%) were found to have FBD, whereas in the control group, only 18 out of 55 (32.7%) had FBD. Statistical analysis using the chi-square test demonstrated a significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.003), indicating a positive association between PCOS and an increased risk of FBD.

3.4. Phenotype-based analysis

The PCOS group was further classified into 4 phenotypes according to the Rotterdam criteria. The prevalence of FBD within each phenotype was as follows: phenotype A (hyperandrogenism + anovulation + polycystic ovaries; n = 22) had the highest prevalence at 81.8% (18/22), followed by phenotype B (hyperandrogenism + anovulation; n = 15) at 66.7% (10/15), phenotype C (hyperandrogenism + polycystic ovaries; n = 12) at 58.3% (7/12), and phenotype D (anovulation + polycystic ovaries; n = 11) at 36.4% (4/11). Chi-square analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in FBD prevalence among the PCOS phenotypes (p = 0.01), indicating that certain phenotypes may confer a higher risk for developing FBD.

As shown, the highest prevalence of FBD was observed in phenotype A, with 81.8% of individuals affected. Chi-square analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in FBD prevalence among the PCOS phenotypes (p = 0.01), indicating that certain phenotypes may confer a higher risk for developing FBD (Table III).

3.5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

To identify independent predictors of FBD, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted. The presence of PCOS was independently associated with increased odds of FBD (odds ratio [OR] = 3.12; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.51-6.45; p = 0.002). Furthermore, phenotype A exhibited a significantly higher risk of FBD compared to phenotype D (OR = 4.9; p = 0.001) (Figure 1).

3.6. Metabolic results

Evaluation of metabolic parameters between the PCOS and FBD groups revealed statistically significant differences in several indices. Women with PCOS had higher FBG, insulin levels, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, indicating a greater degree of insulin resistance. Additionally, the lipid profile analysis showed elevated triglyceride and LDL levels and lower HDL levels in the PCOS group compared to the FBD group (Table II).

- Insulin resistance was notably higher in the PCOS group, as shown by elevated insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance values.

- Dyslipidemia was more common in PCOS women, characterized by higher triglycerides and LDL, and lower HDL levels.

- These findings support the presence of underlying metabolic disturbances in women with PCOS, which may contribute to the pathophysiology of associated conditions such as FBD.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of FBD among women with PCOS compared to the control group (58.3% vs. 30%, p = 0.003). Among PCOS phenotypes, phenotype A -characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM- showed the highest FBD prevalence (81.8%). Logistic regression analysis confirmed that the presence of PCOS increased the odds of FBD more than threefold (OR = 3.12; 95% CI: 1.51-6.45). Additionally, women with PCOS exhibited significant hormonal imbalances (elevated LH, AMH, and testosterone) and metabolic disturbances (higher insulin resistance and dyslipidemia), which may contribute to breast tissue alterations.

In addition to phenotype-based associations, our study also evaluated individual hormonal variables. Levels of AMH, LH, and testosterone were significantly elevated in the PCOS group compared to controls, confirming the characteristic hormonal imbalance of PCOS. Elevated AMH reflects ovarian follicular excess and dysfunction and may indirectly contribute to breast tissue changes. Similarly, the increased LH/FSH ratio was consistent with prior findings in PCOS populations (15, 16). In contrast, estrogen and progesterone levels did not significantly differ between groups, which aligns with earlier reports showing relatively preserved gonadal steroid production in PCOS. Taken together, these hormonal patterns -particularly high AMH and LH/FSH ratio combined with hyperandrogenism- along with metabolic abnormalities may provide a plausible mechanistic pathway linking PCOS to the increased prevalence of FBD.

These findings suggest a strong association between PCOS -especially more severe phenotypes- and an increased risk of FBD. The results align with some previous reports while contrasting with others, highlighting the need for phenotype-based interpretation and further investigation into hormonal interactions affecting breast tissue.

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age and is associated with a spectrum of hormonal, metabolic, and reproductive abnormalities. The current study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of FBD among women with PCOS compared to those without the syndrome. This finding contrasts with some earlier reports that failed to establish a clear association between PCOS and benign breast conditions (17, 18).

In this study, the overall prevalence of FBD in the PCOS group reached 58.3%, with an especially high rate of 81.8% observed among women with phenotype A (characterized by hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM). This finding aligns with a previous study that also reported significant differences in FBD prevalence among different PCOS phenotypes. However, in contrast to our results, the study suggested that hyperandrogenism -particularly elevated free testosterone- might exert a protective effect against FBD (19). This contrasts with our findings, which demonstrated a higher prevalence of FBD in phenotypes with elevated androgen levels. Such discrepancies may stem from differences in phenotypic definitions, population characteristics, or FBD diagnostic methods across studies.

A recent systematic review concluded that no clear link was observed between PCOS and BBD (1). However, the differences in study design (cross-sectional vs. systematic review), sample selection methods, and lack of phenotypic analysis in that review may explain the divergent results. Notably, the present study’s stratification by PCOS phenotypes is a methodological strength that allows for more nuanced interpretation (20).

A recent investigation conducted among postmenopausal women reported that a history of PCOS in the premenopausal period increased the risk of developing fibrocystic changes after menopause. This is consistent with our findings in a reproductive-age population and may reflect the long-term effects of hormonal disturbances in PCOS on breast tissue architecture (21).

Earlier research has similarly found a higher prevalence of BBD among women with polycystic ovaries (PAO) and PCOS, as confirmed by pelvic ultrasound and mammography. This provides further support for a potential relationship between PCOS and breast tissue alterations (1).

Conversely, a comprehensive review exploring long-term outcomes of PCOS, including breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers, highlighted a complex and often inconsistent relationship (22, 23). While PCOS was clearly associated with endometrial cancer, the evidence for breast cancer and FBD was inconclusive. This underscores the need for well-designed studies with detailed phenotypic characterization and control for potential confounding factors (24).

Overall, the results of this study support the hypothesis that hormonal and metabolic disturbances associated with PCOS -particularly in more severe phenotypes- may contribute to fibrocystic changes in breast tissue (23, 25). However, discrepancies among studies emphasize the importance of phenotype-based analyses and consideration of population and methodological differences. Further prospective, large-scale investigations are warranted to better understand the underlying mechanisms linking PCOS with benign breast pathologies.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights a noteworthy link between PCOS and FBD, particularly among women with the more hormonally and metabolically severe phenotypes of PCOS. The significantly higher prevalence of FBD in phenotype A suggests that the interplay of hyperandrogenism, anovulation, and PCOM may influence the development of benign breast changes. These findings point to a shared hormonal and metabolic pathophysiology underlying both conditions. Given the widespread occurrence of PCOS among women of reproductive age and its broad spectrum of systemic effects, the association with FBD adds an important dimension to the clinical implications of the disorder. This reinforces the need for routine breast health screening in women with PCOS, especially those exhibiting complex phenotypic features. In a broader context, the results of this study underscore the interconnectedness of endocrine and reproductive health in women. Recognizing these associations not only helps clinicians deliver more comprehensive care but also contributes to early detection and prevention strategies. Future longitudinal and mechanistic studies are warranted to explore the causal pathways linking PCOS and BBDs, ultimately improving women's health outcomes across the lifespan.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

R. Baradaran Bagheri and S.S. Mirrahimi designed the study and conducted the research. L. Hajimaghsoudi and R. Baradaran Bagheri are supervisor and write the draft of manuscript. A. Mahmoudnezhad Atash beyg, R. Baradaran Bagheri monitored, evaluated, and analyzed the results of the study. R. Baradaran Bagheri reviewed the article. All authors approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article sincerely thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran and Clinical Research Development Unit of Tabriz Valiasr hospital, Tabriz, Iran for their unwavering support and assistance in this research. We also extend our gratitude to the developers of the DeepSeek AI tool, which was used to enhance the quality of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Endocrinology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |