Sat, Jul 5, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 18, Issue 5 (May 2020)

IJRM 2020, 18(5): 319-326 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Davar R, Dashti S, Omidi M. Endometrial preparation using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist prior to frozen-thawed embryo transfer in women with repeated implantation failure: An RCT. IJRM 2020; 18 (5) :319-326

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-1467-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-1467-en.html

1- Research and Clinical Center for Infertility, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Research and Clinical Center for Infertility, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,saeideh_dashti@yahoo.com

2- Research and Clinical Center for Infertility, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

Keywords: Implantation failure, Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone, Embryo transfer, Pregnancy, Implantation.

Full-Text [PDF 300 kb]

(1458 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2452 Views)

One of the main challenges of ART programs is repeated implantation failure (RIF). Several treatment strategies have been suggested for this problem (7). FET cycles can be timed with ovulation in natural cycles or after endometrial preparation following exogenous hormone therapy (3, 6). Another protocol for controlled endometrial preparation is using the GnRH agonist prior to steroid administration, resulting in ovarian function suppression, subsequently creating synchronization between endometrial and embryo development (8). Several studies showed significant improvements in pregnancy rates for both fresh (9, 10) and frozen cycles (11) following GnRH agonist administration in infertile women with endometriosis or adenomyosis. Specifically, in FET cycles, it was reported that pretreatment with a GnRH agonist in patients with adenomyosis improved endometrial receptivity, as well as pregnancy outcomes (11).

The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of GnRH agonist administration on the implantation rate in the FET cycles of women with RIF, prior to estrogen-progesterone preparation of the endometrium.

The case group (n = 34) received 0.1 mg/day of the GnRH agonist (Variopeptyl, VarianDarou, Iran), subcutaneous, from day 21 of the cycle preceding the actual FET cycle. On the second day of the cycle, the dose of GnRH agonist was reduced to 0.05 mg and 6 mg/day oral estradiol valerate (2 mg, Aburaihan Co., Tehran, Iran) was also started. When the endometrial thickness reached to 7.5 mm, vaginal supplementation of Cyclogest® pessaries (Cox Pharmaceuticals, Barnstaple, UK) at 400 mg twice daily was started and the GnRH agonist was also stopped.

The control group (n = 33), received 6 mg/day oral estradiol valerate (2 mg, Aburaihan Co., Tehran, Iran) from the second day of the cycle without the GnRH agonist. In the two groups, frozen-thawed embryos were transferred on the fourth day of progesterone treatment. All women with endometrial polyp, uterine myoma, and uterine anomaly were excluded from the study (Figure 1).

2.4. Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.RSI.Rec.1396.1). Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS v. 14, Chicago, IL). Both Mann-Whitney U and chi-square tests were performed where appropriate. The level of significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

In the case group, three cycles were canceled due to ovarian cyst (37 mm), endometrial failure to reach a thickness of at least 7.5 mm, and no embryo survival after thawing procedure. Two cycles were also canceled in the control group because no embryo survived following the thawing procedure.

Finally, the number of cycles remaining was 31 in each group. No participants were lost to follow-up in either group. No significant differences in the demographic characteristics were observed between the two groups (Table I). The two groups were similar in endometrial thickness at the start of progesterone therapy (8.70 ± 1.08 vs. 8.94 ± 1.33, p = 0.521) and in the number and quality of transferred embryo per women (1.90 ± 30 vs. 1.83 ± .52, p = 0.554) (Table I).

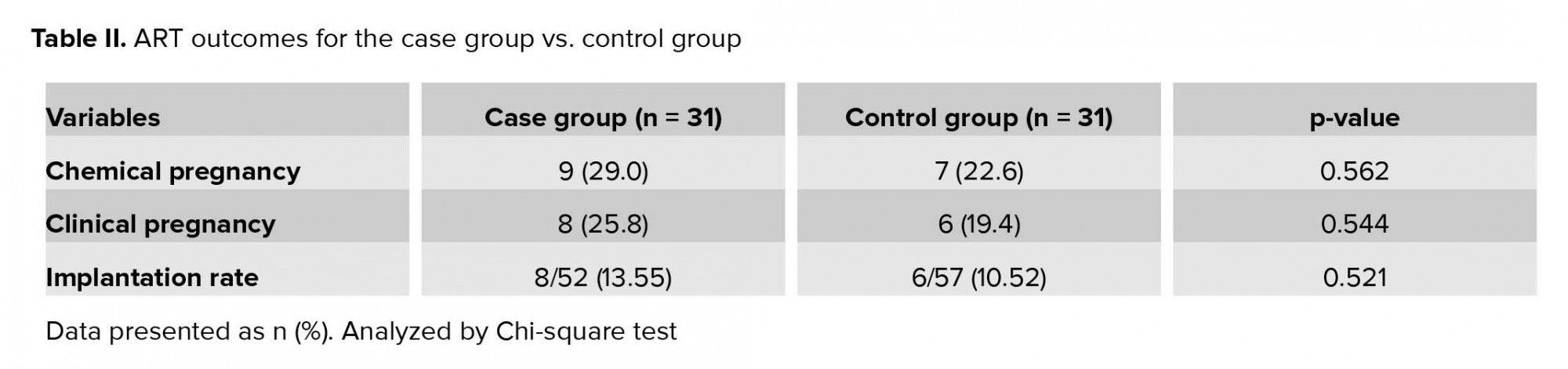

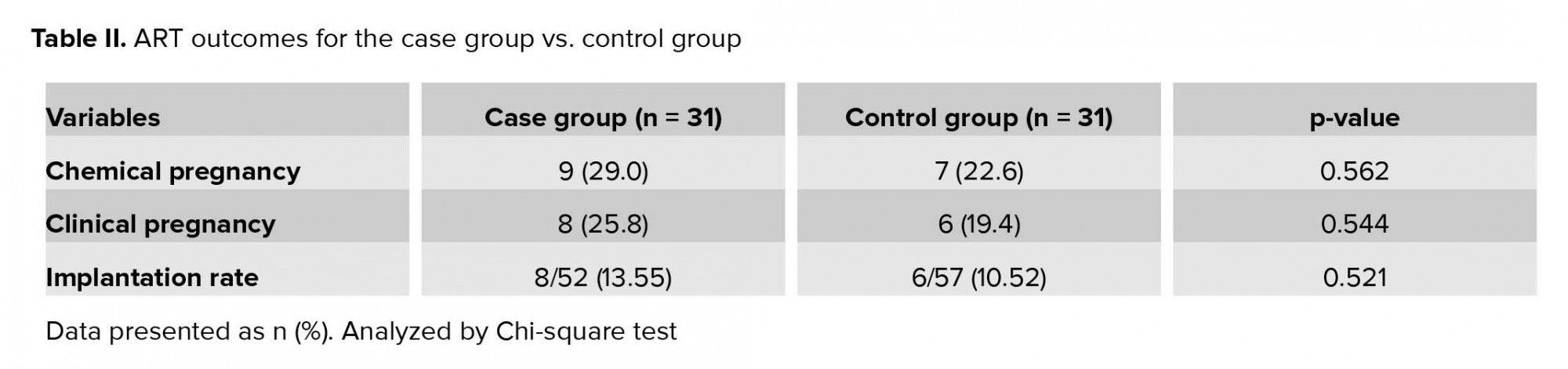

As presented in Table II, the ART outcomes in the two groups were not significantly different. Data showed higher chemical and clinical pregnancy rates for the case group than the control group (29% vs. 22.6% and 25.8% vs. 19.4%, respectively); however, differences were not significant. Moreover, implantation rate showed no statistically significant difference between groups; however, there was a trend toward greater implantation rate in the case group (13.55% vs. 10.52%, p = 0.521).

4. Discussion

The present study found that pituitary down-regulation prior to frozen ET did not lead to significantly higher chemical and clinical pregnancy rates in women with a history of RIF.

RIF is an important challenge in ART programs for both patients and physicians. An important factor in implantation is synchronization between embryo development and endometrial maturation. One study have evaluated other factors that may affect or improve ART outcome of frozen-thawed embryos (1).

The programmed cycle using a GnRH agonist prior to estrogen and progesterone administration aims to effect pituitary down-regulation, thereby avoiding spontaneous ovulation and cycle cancelation, the primary drawbacks of a natural cycle protocol (12). Our study revealed that the GnRH agonist in women with RIF may improve implantation and pregnancy rates; however, indicated differences showed no level of significance. Hebisha and colleagues showed that daily subcutaneous administration of 0.1 mg GnRH agonist (Triptorelin) prior to estrogen and progesterone (starting from the mid-luteal phase of the previous cycle) increased implantation and pregnancy rates (13). A recent study related to sample size also delivered meaningful results. The implementation of a smaller case group in our study was the reason we did not report significant statistical results. Furthermore, using the GnRH agonist prior to frozen ET in polycystic ovary syndrome, women indicated an improvement in ongoing pregnancy rate (14).

Similarly, Xing and associates found that hormonally controlled endometrial preparation with prior GnRH agonist suppression can be used for patients who had experienced repeated IVF treatment failures, despite having morphologically optimal embryos. This study administered two intramuscular injections of Diphereline (2.5 mg), with a duration time of 28 days between the first and second injection. The comparison showed that clinical outcomes were significantly better with GnRH agonist protocols when compared with endometrial preparation with estrogen and progesterone only protocols in the same patients (15). Generally, the underlying mechanism of a GnRH agonist is not yet clearly understood. Probably It seems that induces pituitary suppression and decreased circulating estrogen, a GnRH agonist may reduce concentrations of peritoneal fluid metalloproteinase tissue inhibitors, down-regulate peritoneal fluid inflammatory proteins, and promote apoptosis and expression of pro-apoptotic proteins (16, 17). Niu and colleagues showed using long-term GnRH agonist prior to IVF/ICSI in infertile women with endometriosis or adenomyosis significantly enhanced the chances of pregnancy in both fresh and frozen cycles (11). In fact, it was found that women with repeated implantation failure have concomitant uterine adenomyosis and a prominent aggregation of macrophages within the superficial endometrial glands, that interrupted with embryo implantation. Tremellen and colleagues showed that pituitary suppression with a GnRH agonist increased implantation rate (18).

In agreement with our result, Dal and colleagues reported no difference in implantation and pregnancy rates with or without the use of a GnRH agonist for pituitary suppression in FET cycles. They administered 3.75 mg Decapeptyl in the mid-luteal phase of the cycle. Their results indicated that endometrial preparation with GnRH agonist pretreatment did not increase the success rate of FET cycles (19). Previously, we found no significant different implantation or pregnancy rates when using exogenous steroids with or without GnRH agonist during FET cycles (20).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found that the use of a GnRH agonist in women with RIF may improve endometrial receptivity and increase pregnancy rate. However, differences were not statistically significant. Therefore, additional large prospective studies are necessary on this topic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the infertility Clinic as well as the operating room personnel at Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Yazd, Iran for their valuable contributions to all procedures. Financial support was done by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Full-Text: (539 Views)

- Introduction

One of the main challenges of ART programs is repeated implantation failure (RIF). Several treatment strategies have been suggested for this problem (7). FET cycles can be timed with ovulation in natural cycles or after endometrial preparation following exogenous hormone therapy (3, 6). Another protocol for controlled endometrial preparation is using the GnRH agonist prior to steroid administration, resulting in ovarian function suppression, subsequently creating synchronization between endometrial and embryo development (8). Several studies showed significant improvements in pregnancy rates for both fresh (9, 10) and frozen cycles (11) following GnRH agonist administration in infertile women with endometriosis or adenomyosis. Specifically, in FET cycles, it was reported that pretreatment with a GnRH agonist in patients with adenomyosis improved endometrial receptivity, as well as pregnancy outcomes (11).

The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of GnRH agonist administration on the implantation rate in the FET cycles of women with RIF, prior to estrogen-progesterone preparation of the endometrium.

- Materials and Methods

- 1.Participants

The case group (n = 34) received 0.1 mg/day of the GnRH agonist (Variopeptyl, VarianDarou, Iran), subcutaneous, from day 21 of the cycle preceding the actual FET cycle. On the second day of the cycle, the dose of GnRH agonist was reduced to 0.05 mg and 6 mg/day oral estradiol valerate (2 mg, Aburaihan Co., Tehran, Iran) was also started. When the endometrial thickness reached to 7.5 mm, vaginal supplementation of Cyclogest® pessaries (Cox Pharmaceuticals, Barnstaple, UK) at 400 mg twice daily was started and the GnRH agonist was also stopped.

The control group (n = 33), received 6 mg/day oral estradiol valerate (2 mg, Aburaihan Co., Tehran, Iran) from the second day of the cycle without the GnRH agonist. In the two groups, frozen-thawed embryos were transferred on the fourth day of progesterone treatment. All women with endometrial polyp, uterine myoma, and uterine anomaly were excluded from the study (Figure 1).

- 2. Embryo vitrification and thawing

- 3. Clinical outcomes

2.4. Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (Code: IR.SSU.RSI.Rec.1396.1). Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS v. 14, Chicago, IL). Both Mann-Whitney U and chi-square tests were performed where appropriate. The level of significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

In the case group, three cycles were canceled due to ovarian cyst (37 mm), endometrial failure to reach a thickness of at least 7.5 mm, and no embryo survival after thawing procedure. Two cycles were also canceled in the control group because no embryo survived following the thawing procedure.

Finally, the number of cycles remaining was 31 in each group. No participants were lost to follow-up in either group. No significant differences in the demographic characteristics were observed between the two groups (Table I). The two groups were similar in endometrial thickness at the start of progesterone therapy (8.70 ± 1.08 vs. 8.94 ± 1.33, p = 0.521) and in the number and quality of transferred embryo per women (1.90 ± 30 vs. 1.83 ± .52, p = 0.554) (Table I).

As presented in Table II, the ART outcomes in the two groups were not significantly different. Data showed higher chemical and clinical pregnancy rates for the case group than the control group (29% vs. 22.6% and 25.8% vs. 19.4%, respectively); however, differences were not significant. Moreover, implantation rate showed no statistically significant difference between groups; however, there was a trend toward greater implantation rate in the case group (13.55% vs. 10.52%, p = 0.521).

4. Discussion

The present study found that pituitary down-regulation prior to frozen ET did not lead to significantly higher chemical and clinical pregnancy rates in women with a history of RIF.

RIF is an important challenge in ART programs for both patients and physicians. An important factor in implantation is synchronization between embryo development and endometrial maturation. One study have evaluated other factors that may affect or improve ART outcome of frozen-thawed embryos (1).

The programmed cycle using a GnRH agonist prior to estrogen and progesterone administration aims to effect pituitary down-regulation, thereby avoiding spontaneous ovulation and cycle cancelation, the primary drawbacks of a natural cycle protocol (12). Our study revealed that the GnRH agonist in women with RIF may improve implantation and pregnancy rates; however, indicated differences showed no level of significance. Hebisha and colleagues showed that daily subcutaneous administration of 0.1 mg GnRH agonist (Triptorelin) prior to estrogen and progesterone (starting from the mid-luteal phase of the previous cycle) increased implantation and pregnancy rates (13). A recent study related to sample size also delivered meaningful results. The implementation of a smaller case group in our study was the reason we did not report significant statistical results. Furthermore, using the GnRH agonist prior to frozen ET in polycystic ovary syndrome, women indicated an improvement in ongoing pregnancy rate (14).

Similarly, Xing and associates found that hormonally controlled endometrial preparation with prior GnRH agonist suppression can be used for patients who had experienced repeated IVF treatment failures, despite having morphologically optimal embryos. This study administered two intramuscular injections of Diphereline (2.5 mg), with a duration time of 28 days between the first and second injection. The comparison showed that clinical outcomes were significantly better with GnRH agonist protocols when compared with endometrial preparation with estrogen and progesterone only protocols in the same patients (15). Generally, the underlying mechanism of a GnRH agonist is not yet clearly understood. Probably It seems that induces pituitary suppression and decreased circulating estrogen, a GnRH agonist may reduce concentrations of peritoneal fluid metalloproteinase tissue inhibitors, down-regulate peritoneal fluid inflammatory proteins, and promote apoptosis and expression of pro-apoptotic proteins (16, 17). Niu and colleagues showed using long-term GnRH agonist prior to IVF/ICSI in infertile women with endometriosis or adenomyosis significantly enhanced the chances of pregnancy in both fresh and frozen cycles (11). In fact, it was found that women with repeated implantation failure have concomitant uterine adenomyosis and a prominent aggregation of macrophages within the superficial endometrial glands, that interrupted with embryo implantation. Tremellen and colleagues showed that pituitary suppression with a GnRH agonist increased implantation rate (18).

In agreement with our result, Dal and colleagues reported no difference in implantation and pregnancy rates with or without the use of a GnRH agonist for pituitary suppression in FET cycles. They administered 3.75 mg Decapeptyl in the mid-luteal phase of the cycle. Their results indicated that endometrial preparation with GnRH agonist pretreatment did not increase the success rate of FET cycles (19). Previously, we found no significant different implantation or pregnancy rates when using exogenous steroids with or without GnRH agonist during FET cycles (20).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found that the use of a GnRH agonist in women with RIF may improve endometrial receptivity and increase pregnancy rate. However, differences were not statistically significant. Therefore, additional large prospective studies are necessary on this topic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the infertility Clinic as well as the operating room personnel at Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Yazd, Iran for their valuable contributions to all procedures. Financial support was done by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Assisted Reproductive Technologies

References

1. 1. Gardner DK, Weissman A, Howles CM, Shoham Z. Textbook of assisted reproductive techniques. 5th Ed. Clinical Perspectives: CRC press; 2017.

2. 2. Yarali H, Polat M, Mumusoglu S, Yarali I, Bozdag G. Preparation of endometrium for frozen embryo replacement cycle: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016; 33: 1287-1304.

3. 3. Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C, Thomas S. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer in normal responders. Fertil Steril 2011; 96: 344‐348.

4. 4. Ming L, Liu P, Qiao J, Lian Y, Zheng X, Ren X, et al. Synchronization between embryo development and endometrium is a contributing factor for rescue ICSI outcome. Reprod Biomed Online 2012; 24: 527-531.

5. 5. Groenewoud ER, Cantineau AE, Kollen BJ, Macklon NS, Cohlen BJ. What is the optimal means of preparing the endometrium in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycle? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Updat 2013; 19: 458-470.

6. 6. Ozgur K, Berkkanoglu M, Bulut H, Humaidan P, Coetzee K. Agonist depot versus OCP programming of frozen embryo transfer: a retrospective analysis of freeze-all cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016; 33: 207-214.

7. 7. Makrigiannakis A, BenKhalifa M, Vrekoussis T, Mahjub S, Kalantaridou SN, Gurgan T. Repeated implantation failure: a new potential treatment option. Eur J Clin Invest 2015; 45: 380-384.

8. 8. Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, Sola I, Geber S, Carreras R, et al. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2013; 99: 156-162.

9. 9. Guo S, Zhang D, Niu Z, Sun Y, FengY. Pregnancy outcomes and neonatal outcomes after pituitary down-regulation in patients with adenomyosis receiving IVF/ICSI and FET. Results of a retrospective cohort study. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016; 9: 14313-14320.

10. 10. Surrey ES, Silverberg KM, Surrey MW, Schoolcraft WB. Effect of prolonged gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy on the outcome of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2002; 78: 699-704.

11. 11. Niu Z, Chen Q, Sun Y, Feng Y. Long-term pituitary downregulation before frozen embryo transfer could improve pregnancy outcomes in women with adenomyosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2013; 29: 1026-1030.

12. 12. Yang X, Dong X, Huang K, Wang L, Xiong T, Ji L, et al. The effect of accompanying dominant follicle development/ovulation on the outcomes of frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer in HRT cycle. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013; 6: 718-723.

13. 13. Hebisha SA, Adel HM. GnRh agonist treatment improves implantation and pregnancy rates of frozen-thawed embryos transfer. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2017; 67: 133-136.

14. 14. Tsai HW, Wang PH, Lin LT, Chen SN, Tsui KH. Using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist before frozen embryo transfer may improve ongoing pregnancy rates in hyperandrogenic polycystic ovary syndrome women. Gynecol Endocinol 2017; 33: 686-689.

15. 15. Yang X, Huang R, Wang YF, Liang XY. Pituitary suppression before frozen embryo transfer is beneficial for patients suffering from idiopathic repeated implantation failure. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2016; 36: 127-131.

16. 16. Ferrero S, Gillott DJ, Remorgida V, Anserini P, Ragni N, Grudzinskas JG. Proteomic analysis of peritoneal fluid in fertile and infertile women with endometriosis. J Reprod Med 2009; 54: 32-40.

17. 17. Ferrero S, Gillott DJ, Remorgida V, Anserini P, Ragni N, Grudzinskas JG. GnRH analogue remarkably down-regulates inflammatory proteins in peritoneal fluid proteome of women with endometriosis. J Reprod Med 2009; 54: 223-231.

18. 18. Tremellen K, Russell P. Adenomyosis is a potential cause of recurrent implantation failure during IVF treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011; 51: 280-283.

19. 19. Dal Prato L, Borini A, Cattoli M, Bonu MA, Sciajno R, Flamigni C. Endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed embryo transfer with or without pretreatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Fertil Steril 2002; 77: 956-960.

20. 20. Davar R, Eftekhar M, Tayebi N. Transfer of cryopreserved-thawed embryos in a cycle using exogenous steroids with or without prior gonadotropihin-releasing hormone agonist. J Med Sci 2007; 7: 880-883.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |