Tue, Feb 3, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 19, Issue 8 (August 2021)

IJRM 2021, 19(8): 699-706 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Afrakhteh H, Joharinia N, Momen A, Dowran R, Babaei A, Namdari P, et al . Relative frequency of hepatitis B virus, human papilloma virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes simplex viruses in the semen of fertile and infertile men in Shiraz, Iran: A cross-sectional study. IJRM 2021; 19 (8) :699-706

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-1820-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-1820-en.html

Hossin Afrakhteh1

, Negar Joharinia1

, Negar Joharinia1

, Akhtar Momen1

, Akhtar Momen1

, Razieh Dowran1

, Razieh Dowran1

, Abozar Babaei1

, Abozar Babaei1

, Parisa Namdari1

, Parisa Namdari1

, Mohammad Motamedifar2

, Mohammad Motamedifar2

, Behieh Namavar3

, Behieh Namavar3

, Jamal Sarvari *4

, Jamal Sarvari *4

, Negar Joharinia1

, Negar Joharinia1

, Akhtar Momen1

, Akhtar Momen1

, Razieh Dowran1

, Razieh Dowran1

, Abozar Babaei1

, Abozar Babaei1

, Parisa Namdari1

, Parisa Namdari1

, Mohammad Motamedifar2

, Mohammad Motamedifar2

, Behieh Namavar3

, Behieh Namavar3

, Jamal Sarvari *4

, Jamal Sarvari *4

1- Department of Bacteriology and Virology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

2- Department of Bacteriology and Virology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Shiraz HIV/AIDS Research Center, Institute of Health and Department of Bacteriology and Virology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

4- Department of Bacteriology and Virology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Gastroenterohepatology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. ,sarvarij@sums.ac.ir

2- Department of Bacteriology and Virology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Shiraz HIV/AIDS Research Center, Institute of Health and Department of Bacteriology and Virology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

4- Department of Bacteriology and Virology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Gastroenterohepatology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. ,

Keywords: Male infertility, Hepatitis B virus, Human papilloma virus, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes simplex viruses.

Full-Text [PDF 275 kb]

(1308 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2489 Views)

Full-Text: (589 Views)

- Introduction

Inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected and regular sexual intercourse defined as infertility. It has been reported that around 8-12% of couples suffer from infertility worldwide (1), and overall 50% of infertile cases are associated with men (2). The most common condition related with male infertility include varicocele, endocrine disorders, spermatic duct obstruction, anti-sperm antibodies, gonadotoxins, drugs, cryptorchidism, infection, sexual dysfunction, and ejaculatory failure (3). Viruses could infect the genital tract and impair the semen by various mechanisms (4, 5). Several viruses, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and human immunodeficiency virus, have been detected in the semen of asymptomatic men and might be involved in male infertility (4, 6).

HBV is a member of the Hepadenaviridae family, which is transmitted by infected blood and semen (7). HBV DNA has been found in the semen of HBV-infected patients, but not in HBV-negative patients (4). It has been reported that HBV infection has been linked with low quality of sperm resulting increase the frequency of infertility in men (8, 9). Su and colleagues stated that the risk of infertility is higher in HBV-infected men compared to non-infected ones (10). HPV is a nonenveloped double-stranded DNA virus transmitted by sexual contact (11). Gizzo and colleagues showed that HPV infection of the sperm might be involved in decreasing the fertility rate among men through different mechanisms that may influence human embryo development (12). In a review article, Foresta and colleagues reported that the prevalence of HPV semen infection in infertile men is 10-35%; it was also shown that the motility of the sperm in the infected semen sample was lower than in uninfected semen (13).

HSV is a double-stranded DNA virus from the Herpesviridae family (14). The prevalence of this virus in semen varies from 3-50%, depending on the investigation method (15). It has been reported that there is a correlation between the presence of HSV in the semen and a decreased in sperm concentration and reduced motility (4). EBV is a ubiquitous virus that replicates in the epithelial cells and lymphocytes (16). It was found that EBV DNA was present in 40% of cases in equal frequency among normal and abnormal semen (15).

Accordingly, in this study, we aimed to investigate the relative frequency of HBV, HPV, EBV, and HSV infections and their effects on the semen quality and sperm characteristics in fertile and infertile men referred to the Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital, Shiraz, southwestern Iran.

HBV is a member of the Hepadenaviridae family, which is transmitted by infected blood and semen (7). HBV DNA has been found in the semen of HBV-infected patients, but not in HBV-negative patients (4). It has been reported that HBV infection has been linked with low quality of sperm resulting increase the frequency of infertility in men (8, 9). Su and colleagues stated that the risk of infertility is higher in HBV-infected men compared to non-infected ones (10). HPV is a nonenveloped double-stranded DNA virus transmitted by sexual contact (11). Gizzo and colleagues showed that HPV infection of the sperm might be involved in decreasing the fertility rate among men through different mechanisms that may influence human embryo development (12). In a review article, Foresta and colleagues reported that the prevalence of HPV semen infection in infertile men is 10-35%; it was also shown that the motility of the sperm in the infected semen sample was lower than in uninfected semen (13).

HSV is a double-stranded DNA virus from the Herpesviridae family (14). The prevalence of this virus in semen varies from 3-50%, depending on the investigation method (15). It has been reported that there is a correlation between the presence of HSV in the semen and a decreased in sperm concentration and reduced motility (4). EBV is a ubiquitous virus that replicates in the epithelial cells and lymphocytes (16). It was found that EBV DNA was present in 40% of cases in equal frequency among normal and abnormal semen (15).

Accordingly, in this study, we aimed to investigate the relative frequency of HBV, HPV, EBV, and HSV infections and their effects on the semen quality and sperm characteristics in fertile and infertile men referred to the Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital, Shiraz, southwestern Iran.

- Materials and Methods

- 1. Study design and subjects

In this cross-sectional study, 350 subjects were enrolled, including 200 infertile and 150 fertile men who were referred to the Ghadir Mother and Child Hospital affiliated with the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences between August to September 2016. The inclusion criteria for the infertile group was a history of infertility with failure to achieve pregnancy after at least one year of unprotected sexual contact. The exclusion criteria of the case group were disorders which affects the sperm parameters, such as azoospermia, undescended testis hydrocele, varicocele, epididymitis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Additionally, those who had genital lesions associated with HPV and HSV or whose spouses had histories of uterine or ovarian disorders were also excluded from the study. The fertile control group includes men who had at least one child.

Sterile containers were used for semen samples collection by way of masturbation after three days of sexual abstinence. Then semen sample quickly transported to the laboratory and stored at -20ºC for further examination. The subjects were advised to wash their hands and genital area with soap and water prior to sampling.

Sterile containers were used for semen samples collection by way of masturbation after three days of sexual abstinence. Then semen sample quickly transported to the laboratory and stored at -20ºC for further examination. The subjects were advised to wash their hands and genital area with soap and water prior to sampling.

- 2. Semen analysis and HBV, EBV, HPV, and HSV detection

All semen samples put in incubator for 30 min at 37ºC. Sperm parameters were determined according to the world health organization guidelines. Then, DNA extraction was performed using DNA extraction kit (CinaGene, Tehran, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The extracted DNA was stored at -20ºC until analysis. Detection of HBV, HPV, EBV, and HSV1/2 was performed by the PCR method.

- 3. HBV PCR conditions

Detection of the HBV genome was done using the HBV PCR detection kit (Sinacolon, Tehran, Iran) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After that, the PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gels.

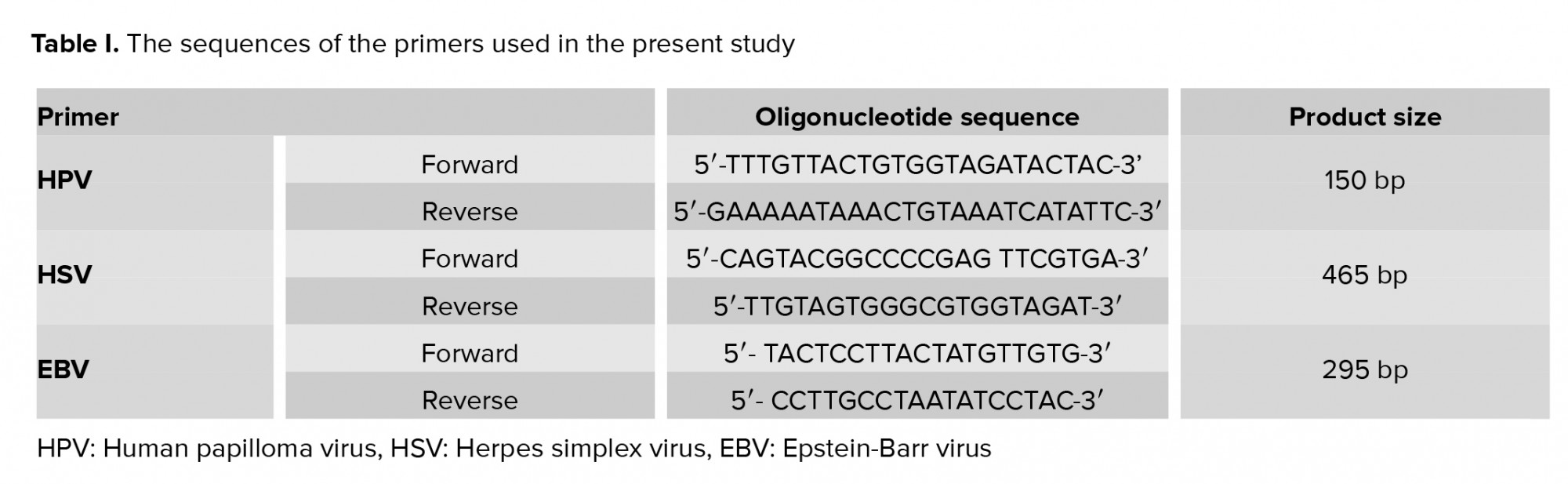

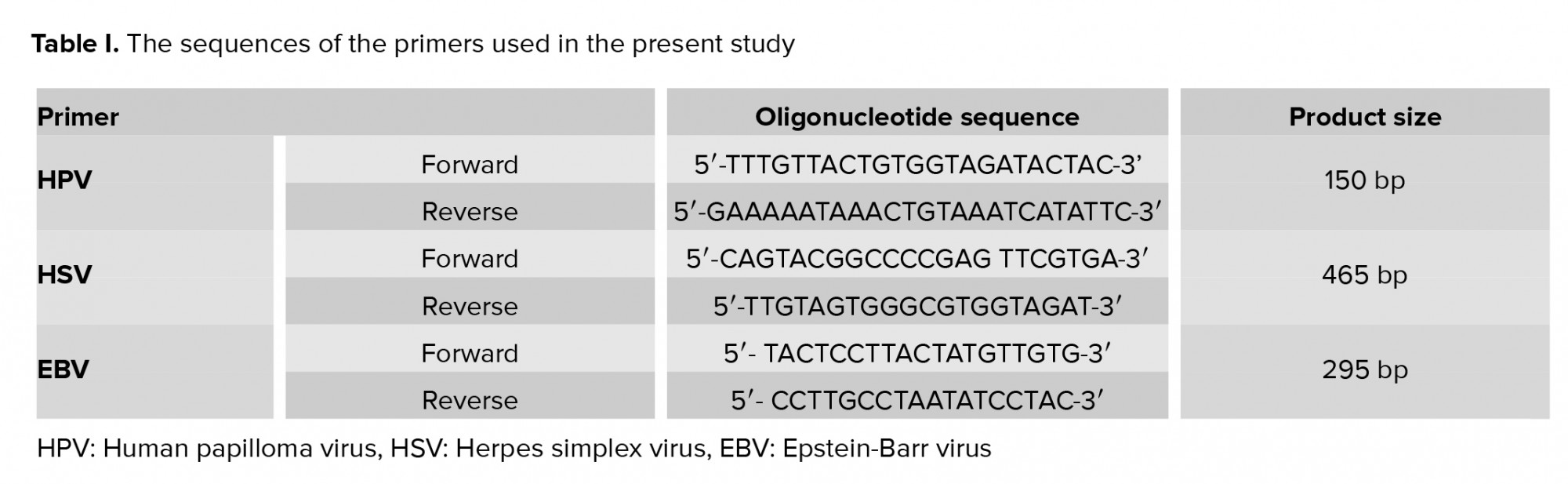

- 4. HPV PCR conditions

HPV detection was performed by universal GP5/6 primers. PCR reaction components were Ampliqon 2x PCR mix red (Amplicon, Denmark, Odense) and 0.4 µM of each primer in 25 µL final volume. Subsequently, amplification was done in conditions including five min initial denaturation at 95ºC, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95ºC for 45 sec, annealing at 55ºC for 45 sec, extension at 72ºC for 45 sec, and a final extension at 72ºC for 10 min. The PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel.

- 5. EBV PCR conditions

Allele ID 7 software were used to designed the sequences of primers specific for BHRF1 region of the EBV genome (Table I). Ampliqon 2x PCR mix red (Ampliqon, Denmark, Odense) plus 0.4 µM of each primer in 25 µL final volume were used for PCR reaction. Amplification was carried out as follows: initial denaturation at 95ºC for 10 min, 45 cycles of denaturation at 95ºC for 45 sec, annealing at 57.6ºC for 45 sec, extension at 72ºC for 45 sec, and a final extension at 72ºC for 10 min. PCR products were then loaded onto a 2% agarose gel and visualized under UV light. The DNA extracted from the B-95 cell line (Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran) was used as a positive control for EBV in each run.

- 6. HSV PCR conditions

HSV detection was performed by common HSV1- and 2-specific primers (Table I). PCR reaction components included Ampliqon 2x PCR mix red (Amplicon, Denmark, Odense) and 0.4 µM of each primer in 25 µL final volume. Amplification was carried out as follow: denaturation at 95ºC for 10 min, 45 cycles of denaturation at 95ºC for 45 sec, annealing at 58ºC for 45 sec, extension at 72ºC for 45 sec, and a final extension at 72ºC for 10 min. The PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel.

The frequency of some bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Lactobacillus, Chlamydia, Neisseria, Helicobacter, Mycoplasma, Citrobacter, Hemophilus, E. coli, and Klebsiella was also detected in this sample. Coinfection of HBV with a bacterial infection occured with the following frequencies: Staphylococcus infection 4.8% (1 out of 21), Lactobacillus 4.8% (1 out of 21), Chlamydia 4.8% (1 out of 21), and Neisseria 9.5% (2 out of 21). No coinfection of HBV with Helicobacter, Mycoplasma, Citrobacter, Hemophilus, E. coli, or Klebsiella was found (17).

It has been reported that progressive motility and percentage of normal sperm morphology in infertile men infected with were significantly lower in comparison with HPV-negative cases (21). Also, a significant association of HSV infection with a lower seminal volume and a lower mean sperm count was reported (22). Moreover, another study showed that sperm motility and normal sperm morphology were significantly negatively affected in HBV-positive men (23).

The results showed that 8% and 3.3% samples of infertile and fertile men were positive for HBV, respectively, which was not statistically significant. Moreover, only one sample of the fertile men was positive for HPV. Furthermore, none of the semen samples of the infertile or fertile groups was positive for the presence of EBV or HSV1/ 2.

Although more semen samples of our infertile participants were positive for HBV than of the fertile group, the difference was not statistically significant. In agreement with our study, Zangeneh and colleagues reported that the frequency of HBV in infertile persons who they studied was very low and was not statistically different from fertile men (24). A study in Ahvaz also showed a very low frequency of HBsAg among infertile couples (25).

Moreover, it has been reported that none of the semen samples of infertile men who they examined were positive for HBV DNA and the mentioned that the low prevalence of HBV infection in their population might have been the cause of the negative results (26). On the other hand, a case-control study that compared men with HBV infection to those without HBV showed an increased risk of infertility in HBV-infected men (8). Also, in a systematic review, it was stated that HBV infection could cause male infertility (4). Therefore, according to the mentioned studies, it seems that the low prevalence of HBV infection in infertile persons, as well as the small sample size of our study groups, may have influenced the HBV association with male infertility.

In the case of HPV, only one of the fertile group participants and none of the infertile participants were positive for HPV. In this regard, Bezold and colleagues reported that 4.5% of the semen samples of infertile men who they studied were infected with HPV (26). In contrast, some studies have reported a significantly higher prevalence of HPV in infertile groups and have also shown a significantly lower sperm motility and count in HPV-infected semen (27-30). Moreover, a systematic review mentioned that HPV infection might cause male infertility, but available data are conflicting (4). Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Lyu et al. showed a twofold increased risk of infertility in men with HPV-infected semen (31).

Semen samples of both fertile and infertile participants were negative for EBV. In agreement, Bezold and colleagues reported that EBV was detected in only one of the samples they examined (26). A study conducted by Neofytou and colleagues showed that although EBV was present in 45% and 39.1% of the semen samples of their fertile and infertile participants, respectively, it was not significantly associated with infertility (15) .Kapranos and colleagues also showed that 16.8% of their study’s semen samples of infertile people were infected with EBV, but there was no association between EBV infection and abnormal sperm motility or semen count (3). Therefore, considering the aforementioned results of the previous studies, it seems that EBV does not have a major role in infertility.

Semen samples of both fertile and infertile participants were negative for HSV1 and HSV2. In line with our results, HSV1 was present in 2.1% and 2.5% of the semen samples of infertile and fertile subjects, respectively, which was again not statistically significant (15). However, the results of a study performed by Monavari and colleagues showed that 20 and 15% of their infertile participants were infected with HSV1 and 2, respectively (32). Moreover, 56.6% of semen samples of infertile people were infected with HSV1. They also showed that the semen samples infected with HSV1 had significantly lower sperm motility than the non-infected one (3). Moreover, HSV was present in 3.7% of the semen samples of the infertile men and HSV presence was associated with a decrease in sperm count and motility (26). Furthermore, in a review by Ochsendorf et al., a significant relationship was observed between the presence of HSV and infertility (33). According to these studies, it seems that HSV might be involved in infertility at least in some areas, which might be related to a high frequency of HSV infection in those populations.

Acknowledgements

The present study was extracted from the thesis written by Akhtar Momen and Hossein Afrakhteh and financially supported by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 94-10057 and 96-16400).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

- 7. Ethical considerations

- 8. Statistical analysis

- Results

- 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

- 2. The results of the semen analysis

- 3. The results of HBV, HPV, EBV, and HSV1 and 2 detection through PCR

The frequency of some bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Lactobacillus, Chlamydia, Neisseria, Helicobacter, Mycoplasma, Citrobacter, Hemophilus, E. coli, and Klebsiella was also detected in this sample. Coinfection of HBV with a bacterial infection occured with the following frequencies: Staphylococcus infection 4.8% (1 out of 21), Lactobacillus 4.8% (1 out of 21), Chlamydia 4.8% (1 out of 21), and Neisseria 9.5% (2 out of 21). No coinfection of HBV with Helicobacter, Mycoplasma, Citrobacter, Hemophilus, E. coli, or Klebsiella was found (17).

- Discussion

It has been reported that progressive motility and percentage of normal sperm morphology in infertile men infected with were significantly lower in comparison with HPV-negative cases (21). Also, a significant association of HSV infection with a lower seminal volume and a lower mean sperm count was reported (22). Moreover, another study showed that sperm motility and normal sperm morphology were significantly negatively affected in HBV-positive men (23).

The results showed that 8% and 3.3% samples of infertile and fertile men were positive for HBV, respectively, which was not statistically significant. Moreover, only one sample of the fertile men was positive for HPV. Furthermore, none of the semen samples of the infertile or fertile groups was positive for the presence of EBV or HSV1/ 2.

Although more semen samples of our infertile participants were positive for HBV than of the fertile group, the difference was not statistically significant. In agreement with our study, Zangeneh and colleagues reported that the frequency of HBV in infertile persons who they studied was very low and was not statistically different from fertile men (24). A study in Ahvaz also showed a very low frequency of HBsAg among infertile couples (25).

Moreover, it has been reported that none of the semen samples of infertile men who they examined were positive for HBV DNA and the mentioned that the low prevalence of HBV infection in their population might have been the cause of the negative results (26). On the other hand, a case-control study that compared men with HBV infection to those without HBV showed an increased risk of infertility in HBV-infected men (8). Also, in a systematic review, it was stated that HBV infection could cause male infertility (4). Therefore, according to the mentioned studies, it seems that the low prevalence of HBV infection in infertile persons, as well as the small sample size of our study groups, may have influenced the HBV association with male infertility.

In the case of HPV, only one of the fertile group participants and none of the infertile participants were positive for HPV. In this regard, Bezold and colleagues reported that 4.5% of the semen samples of infertile men who they studied were infected with HPV (26). In contrast, some studies have reported a significantly higher prevalence of HPV in infertile groups and have also shown a significantly lower sperm motility and count in HPV-infected semen (27-30). Moreover, a systematic review mentioned that HPV infection might cause male infertility, but available data are conflicting (4). Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Lyu et al. showed a twofold increased risk of infertility in men with HPV-infected semen (31).

Semen samples of both fertile and infertile participants were negative for EBV. In agreement, Bezold and colleagues reported that EBV was detected in only one of the samples they examined (26). A study conducted by Neofytou and colleagues showed that although EBV was present in 45% and 39.1% of the semen samples of their fertile and infertile participants, respectively, it was not significantly associated with infertility (15) .Kapranos and colleagues also showed that 16.8% of their study’s semen samples of infertile people were infected with EBV, but there was no association between EBV infection and abnormal sperm motility or semen count (3). Therefore, considering the aforementioned results of the previous studies, it seems that EBV does not have a major role in infertility.

Semen samples of both fertile and infertile participants were negative for HSV1 and HSV2. In line with our results, HSV1 was present in 2.1% and 2.5% of the semen samples of infertile and fertile subjects, respectively, which was again not statistically significant (15). However, the results of a study performed by Monavari and colleagues showed that 20 and 15% of their infertile participants were infected with HSV1 and 2, respectively (32). Moreover, 56.6% of semen samples of infertile people were infected with HSV1. They also showed that the semen samples infected with HSV1 had significantly lower sperm motility than the non-infected one (3). Moreover, HSV was present in 3.7% of the semen samples of the infertile men and HSV presence was associated with a decrease in sperm count and motility (26). Furthermore, in a review by Ochsendorf et al., a significant relationship was observed between the presence of HSV and infertility (33). According to these studies, it seems that HSV might be involved in infertility at least in some areas, which might be related to a high frequency of HSV infection in those populations.

The relatively small sample size was a limitation of our study. Using the conventional PCR method and not real-time PCR can be considered as another limitation of this study.

In sum, while a number of studies have shown associations between infertility and HBV, HPV, and HSV, some others do not support these findings. This strong discrepancy may partly come from differences in factors including the sample size, different geographical distribution of the viruses, and lifestyle (sexual behavior) of the studied subjects. Moreover, technical issues including the sensitivity of detection methods (PCR or real-time PCR) as well as differences in the extraction procedures may also explain discrepancies among different studies.- Conclusion

Acknowledgements

The present study was extracted from the thesis written by Akhtar Momen and Hossein Afrakhteh and financially supported by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 94-10057 and 96-16400).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Fertility & Infertility

References

1. Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem 2018; 62: 2-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012] [PMID]

2. Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Hamada A, Chyatte MR. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2015; 13: 37. 1-9. [DOI:10.1186/s12958-015-0032-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Kapranos N, Petrakou E, Anastasiadou C, Kotronias D. Detection of herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus in the semen of men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril 2003; 79: 1566-1570. [DOI:10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00370-4]

4. Garolla A, Pizzol D, Bertoldo A, Menegazzo M, Barzon L, Foresta C. Sperm viral infection and male infertility: Focus on HBV, HCV, HIV, HPV, HSV, HCMV, and AAV. J Reprod Immunol 2013; 100: 20-29. [DOI:10.1016/j.jri.2013.03.004] [PMID]

5. Liu W, Han R, Wu H, Han D. Viral threat to male fertility. Andrologia 2018; 50: e13140. [DOI:10.1111/and.13140] [PMID]

6. Behboudi E, Mokhtari-Azad T, Yavarian J, Ghavami N, Seyed Khorrami SM, Rezaei F, et al. Molecular detection of HHV1-5, AAV and HPV in semen specimens and their impact on male fertility. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2019; 22: 133-138. [DOI:10.1080/14647273.2018.1463570] [PMID]

7. Hashemi SMA, Sarvari J, Fattahi MR, Dowran R, Ramezani A, Hoseini SY. Comparison of ISG15, IL28B and USP18 mRNA levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronic hepatitis B virus infected patients and healthy individuals. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2019; 12: 38-45.

8. Bei HF, Wei RX, Cao XD, Zhang XX, Zhou J. [Hepatitis B virus infection increases the incidence of immune infertility in males]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2017; 23: 431-435. (in China)

9. Qian L, Li Q, Li H. Effect of hepatitis B virus infection on sperm quality and oxidative stress state of the semen of infertile males. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016; 76: 183-185. [DOI:10.1111/aji.12537] [PMID]

10. Su FH, Chang SN, Sung FC, Su CT, Shieh YH, Lin CC, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and the risk of male infertility: A population-based analysis. Fertil Steril 2014; 102: 1677-1684. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.09.017] [PMID]

11. Fields B, Knipe D, Howley P. Fields virology 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

12. Gizzo S, Ferrari B, Noventa M, Ferrari E, Patrelli TS, Gangemi M, et al. Male and couple fertility impairment due to HPV-DNA sperm infection: Update on molecular mechanism and clinical impact--systematic review. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 230263. [DOI:10.1155/2014/230263] [PMID] [PMCID]

13. Foresta C, Noventa M, De Toni L, Gizzo S, Garolla A. HPV-DNA sperm infection and infertility: From a systematic literature review to a possible clinical management proposal. Andrology 2015; 3: 163-173. [DOI:10.1111/andr.284] [PMID]

14. Motamedifar M, Sarvari J, Ebrahimpour A, Emami A. Symptomatic reactivation of HSV infection correlates with decreased serum levels of TNF-α. Iran J Immunol 2015; 12: 27-34.

15. Neofytou E, Sourvinos G, Asmarianaki M, Spandidos DA, Makrigiannakis A. Prevalence of human herpes virus types 1-7 in the semen of men attending an infertility clinic and correlation with semen parameters. Fertil Steril 2009; 91: 2487-2494. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.074] [PMID]

16. Sarvari J, Mahmoudvand S, Pirbonyeh N, safaei A, Hosseini SY. The very low frequency of epstein-barr, jc and bk viruses DNA in colorectal cancer tissues in shiraz, southwest iran. Pol J Microbiol 2018: 67: 73-79. [DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0011.6146] [PMID]

17. Motamedifar M, Malekzadegan Y, Namdari P, Dehghani B, Jahromi B, Sarvari J. The prevalence of bacteriospermia in infertile men and association with semen quality in Southwestern Iran. Infectious Disorders Drug Targets 2018; 20: 198-202. [DOI:10.2174/1871526519666181123182116] [PMID]

18. Cui W. Mother or nothing: The agony of infertility. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88: 1-2. [DOI:10.2471/BLT.10.011210] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Winters BR, Walsh TJ. The epidemiology of male infertility. Urol Clin North Am 2014; 41: 195-204. [DOI:10.1016/j.ucl.2013.08.006] [PMID]

20. Pilatz A, Boecker M, Schuppe HC, Diemer T, Wagenlehner F. [Infektionen und infertilität]. Urologe A 2016; 55: 883-889. (in German) [DOI:10.1007/s00120-016-0151-0] [PMID]

21. Moghimi M, Zabihi-Mahmoodabadi S, Kheirkhah-Vakilabad A, Kargar Z. Significant correlation between high-risk HPV DNA in semen and impairment of sperm quality in infertile men. Int J Fertil Steril 2019; 12: 306-309.

22. Kurscheidt FA, Damke E, Bento JC, Balani VA, Takeda KI, Piva S, et al. Effects of herpes simplex virus infections on seminal parameters in male partners of infertile couples. Urology 2018; 113: 52-58. [DOI:10.1016/j.urology.2017.11.050] [PMID]

23. Yazdi RS, Zangeneh M, Makiani MJ, Gilani MAS. Impact of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection on sperm parameters of infertile men. Int J Reprod Biomed 2019; 17: 551-556.

24. Zangeneh M, Sedaghat Jou M, Sadighi Gilani MA, Jamshidi Makiani M, Sadeghinia S, Salman Yazdi R. The prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections among Iranian infertile couples referring to Royan institute infertility clinic: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed 2018; 16: 595-600. [DOI:10.29252/ijrm.16.9.595] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Nikbakht R, Saadati N, Firoozian F. Prevalence of HBsAG, HCV and HIV antibodies among infertile couples in Ahvaz, South-West Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2012; 5: 393-397. [DOI:10.5812/jjm.2809]

26. Bezold G, Politch JA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Wolff H, Anderson DJ. Prevalence of sexually transmissible pathogens in semen from asymptomatic male infertility patients with and without leukocytospermia. Fertil Steril 2007; 87: 1087-1097. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.109] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Rintala MM, Greénman SE, Pöllänen PP, Suominen JJ, Syrjänen SM. Detection of high-risk HPV DNA in semen and its association with the quality of semen. Int J STD AIDS 2004; 15: 740-743. [DOI:10.1258/0956462042395122] [PMID]

28. Foresta C, Pizzol D, Moretti A, Barzon L, Palù G, Garolla A. Clinical and prognostic significance of human papillomavirus DNA in the sperm or exfoliated cells of infertile patients and subjects with risk factors. Fertil Steril 2010; 94: 1723-1727. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.11.012] [PMID]

29. Moghimi M, Zabihi-Mahmoodabadi S, Kheirkhah-Vakilabad A, Kargar Z. Significant correlation between High-Risk HPV DNA in semen and impairment of sperm quality in infertile men. Int J Fertil Steril 2019; 12: 306-309.

30. Nasseri S, Monavari SH, Keyvani H, Nikkhoo B, Vahabpour Roudsari R, Khazeni M. The prevalence of human papilloma virus (HPV) infection in the oligospermic and azoospermic men. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2015; 29: 272.

31. Lyu Z, Feng X, Li N, Zhao W, Wei L, Chen Y, et al. Human papillomavirus in semen and the risk for male infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 714. [DOI:10.1186/s12879-017-2812-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

32. Monavari SH, Vaziri MS, Khalili M, Shamsi-Shahrabadi M, Keyvani H, Mollaei H, et al. Asymptomatic seminal infection of herpes simplex virus: Impact on male infertility. J Biomed Res 2013; 27: 56-61.

33. Ochsendorf FR. Sexually transmitted infections: Impact on male fertility. Andrologia 2008; 40: 72-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00825.x] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |