Sat, Jan 31, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 22, Issue 3 (March 2024)

IJRM 2024, 22(3): 191-202 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini F, Pahlavan F, Ahmadi F. The categorization of opaque pathologies outside of contrast media in hysterosalpingography which facilitate interpretation: A pictorial review. IJRM 2024; 22 (3) :191-202

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3261-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3261-en.html

1- Department of Reproductive Imaging, Reproductive Biomedicine Research Center, Royan Institute for Reproductive Biomedicine, ACECR, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Reproductive Imaging, Reproductive Biomedicine Research Center, Royan Institute for Reproductive Biomedicine, ACECR, Tehran, Iran. ,dr.ahmadi1390@gmail.com

2- Department of Reproductive Imaging, Reproductive Biomedicine Research Center, Royan Institute for Reproductive Biomedicine, ACECR, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6612 kb]

(836 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1164 Views)

Full-Text: (301 Views)

1. Introduction

Several imaging methods are used to diagnose gynecological diseases and tumors. The first line would be an ultrasound examination with high sensitivity and specificity. In addition to ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging has been used recently (1). It is a complementary imaging method, especially for the detection of cancers, pelvic endometriosis, pelvic floor disorders, indeterminate pelvic mass, and fibromas. However, it is an expensive method (2).

Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy are utilized for gynecologic assessment, infertility in particular. They are used since they have both treatment and diagnostic value; however, they are invasive (3). Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a roentgenological visualization of the inner surface of the cervical canal, uterine isthmus, uterine cavity, and fallopian tubes. It is an inexpensive and non-invasive procedure (4). Not only is it a reliable method for the assessment of fallopian tube patency, but also it can detect intrauterine pathologies and some pelvic pathologies outside of contrast areas (5). An in-depth investigation and interpretation of the opaque areas is therefore essential for obtaining reliable data. Pathologic findings should be followed up and ruled out using ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging methods.

The pelvis consists of a complex compartment with multiple anatomic structures. Knowledge and attention to appearances of these structures and pathologic conditions are crucial to avoid confusion and preserve high diagnostic accuracy when interpreting pelvic findings. Radiologists should be conscious of possible nongynecologic findings in HSG (6). Plain pelvic radiographs contain the pelvic soft tissues, including the uterus, ovaries, muscles, and bladder, the gas patterns of the lower portion of the intestines, and bony structures such as pelvic bone, sacroiliac joints, the lower spine, and hips.

In a properly performed HSG, the endocervix, uterine cavity, and fallopian tubes can be well assessed. In addition, potential anomalies outside of contrast areas of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and other tissues may be seen and should be noticed. Soft tissue pathologies in HSG are visible if they calcify or form soft tissue masses (shadow of soft tissues) (7). HSG can also help evaluate the pathologies of bony structures (8). Puzzling features such as artifacts and foreign bodies in pelvic images might interfere with the interpretation.

This study aimed at presenting and evaluating rarely reported and abnormal opaque findings in HSG. The data were extracted from an archive collected over 50 yr. Images were obtained and sourced by Dr Shahrzad’s imaging center and the collection were donated to the Department of Radiology, Royan Institute for Reproductive Biomedicine, Tehran, Iran.

2. Findings and categories

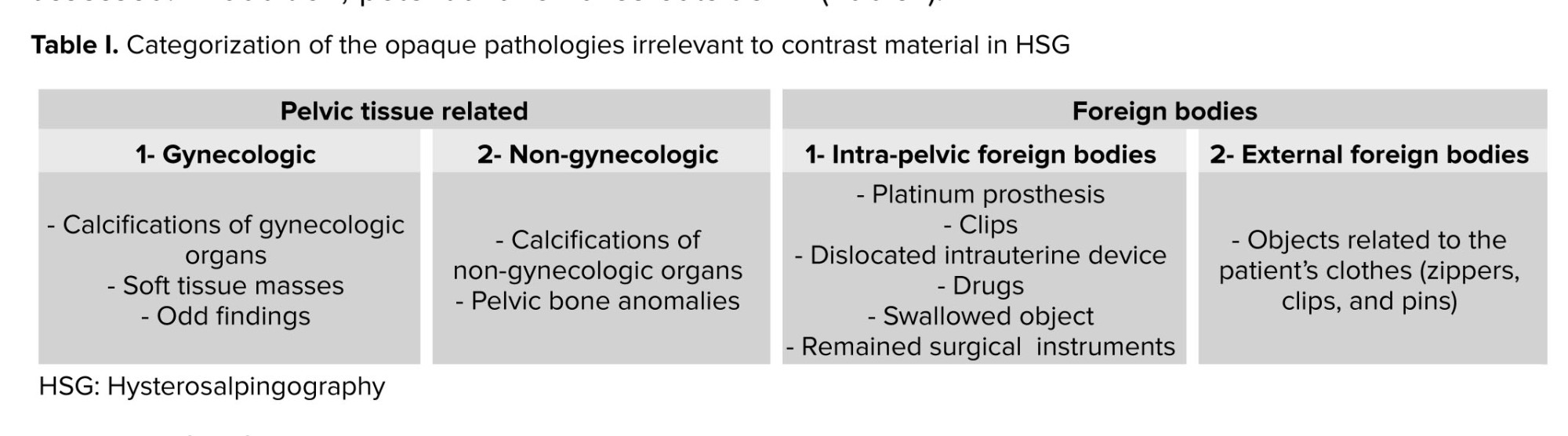

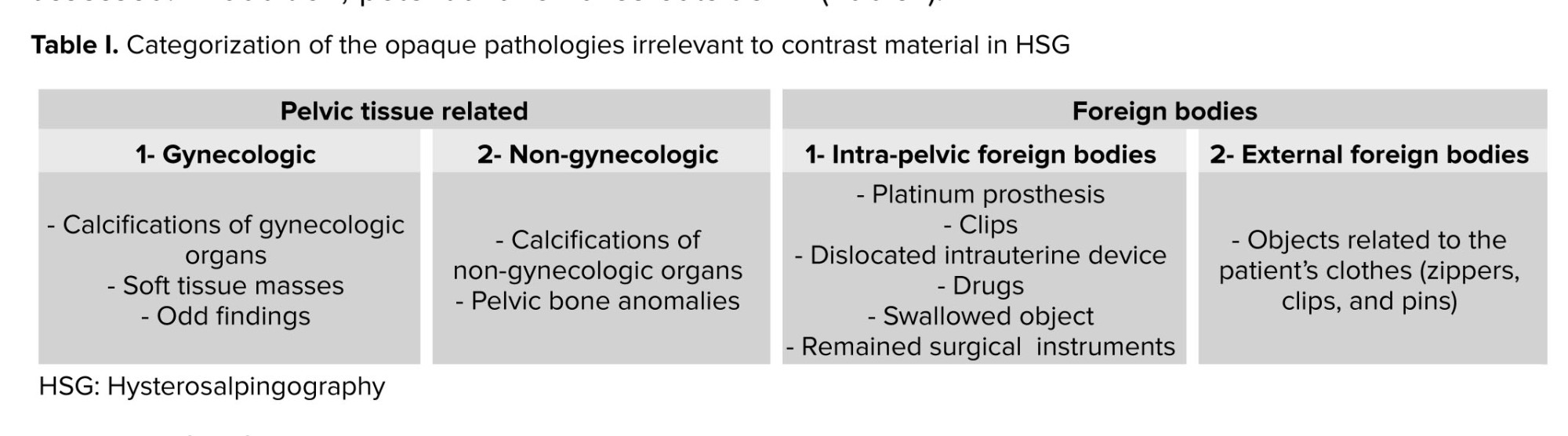

The opaque pathologies irrelevant to contrast material in HSG are categorized into 2 groups (Table I).

2.1. Pelvic tissue related

Pelvic tissue-related anomalies are 1- gynecologic-related or 2- non-gynecologic in type.

Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy are utilized for gynecologic assessment, infertility in particular. They are used since they have both treatment and diagnostic value; however, they are invasive (3). Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a roentgenological visualization of the inner surface of the cervical canal, uterine isthmus, uterine cavity, and fallopian tubes. It is an inexpensive and non-invasive procedure (4). Not only is it a reliable method for the assessment of fallopian tube patency, but also it can detect intrauterine pathologies and some pelvic pathologies outside of contrast areas (5). An in-depth investigation and interpretation of the opaque areas is therefore essential for obtaining reliable data. Pathologic findings should be followed up and ruled out using ultrasound examination and magnetic resonance imaging methods.

The pelvis consists of a complex compartment with multiple anatomic structures. Knowledge and attention to appearances of these structures and pathologic conditions are crucial to avoid confusion and preserve high diagnostic accuracy when interpreting pelvic findings. Radiologists should be conscious of possible nongynecologic findings in HSG (6). Plain pelvic radiographs contain the pelvic soft tissues, including the uterus, ovaries, muscles, and bladder, the gas patterns of the lower portion of the intestines, and bony structures such as pelvic bone, sacroiliac joints, the lower spine, and hips.

In a properly performed HSG, the endocervix, uterine cavity, and fallopian tubes can be well assessed. In addition, potential anomalies outside of contrast areas of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and other tissues may be seen and should be noticed. Soft tissue pathologies in HSG are visible if they calcify or form soft tissue masses (shadow of soft tissues) (7). HSG can also help evaluate the pathologies of bony structures (8). Puzzling features such as artifacts and foreign bodies in pelvic images might interfere with the interpretation.

This study aimed at presenting and evaluating rarely reported and abnormal opaque findings in HSG. The data were extracted from an archive collected over 50 yr. Images were obtained and sourced by Dr Shahrzad’s imaging center and the collection were donated to the Department of Radiology, Royan Institute for Reproductive Biomedicine, Tehran, Iran.

2. Findings and categories

The opaque pathologies irrelevant to contrast material in HSG are categorized into 2 groups (Table I).

2.1. Pelvic tissue related

Pelvic tissue-related anomalies are 1- gynecologic-related or 2- non-gynecologic in type.

2.1.1.Gynecologic related

The uterine cavity and fallopian tubes are visualized as opaque portions in HSG, which normally do not involve other gynecologic organs unless they change through calcification and the growth of new masses, making a soft tissue shadow.

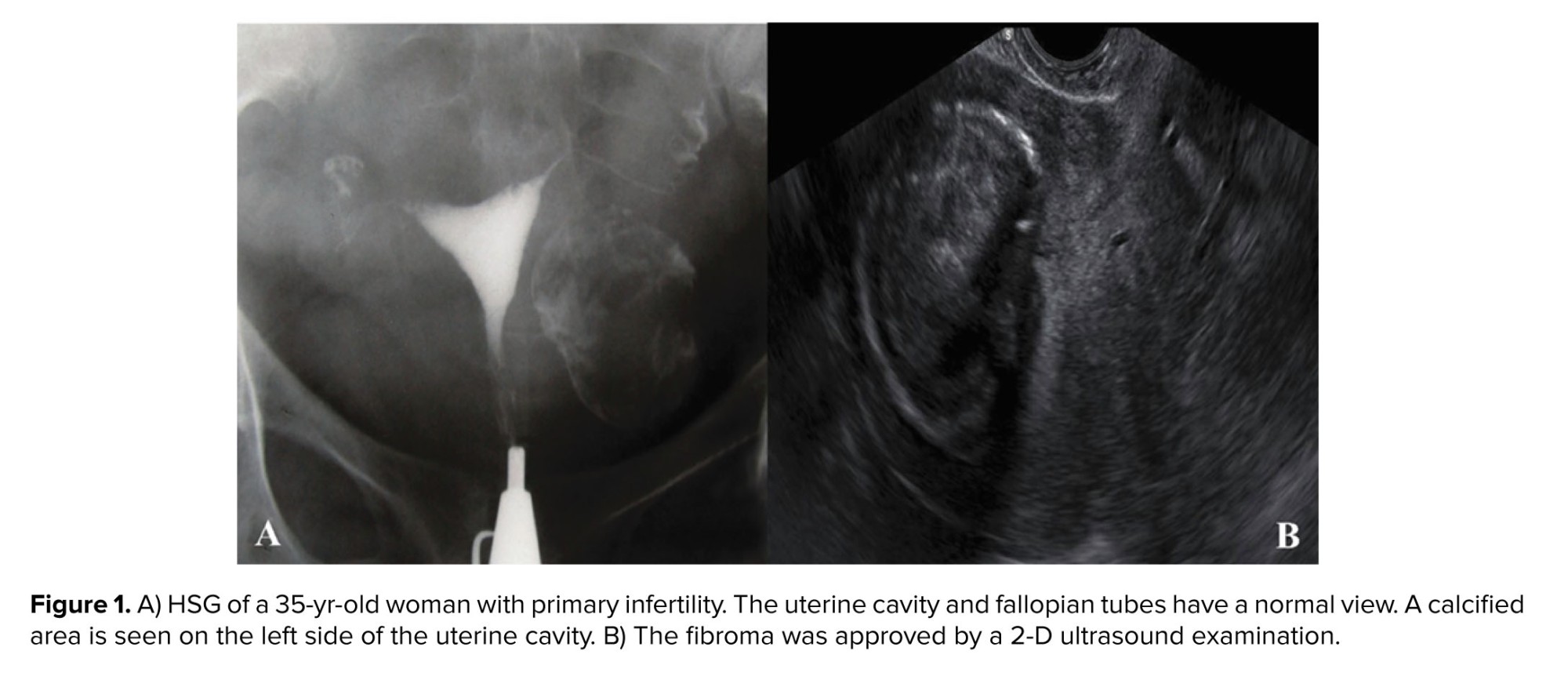

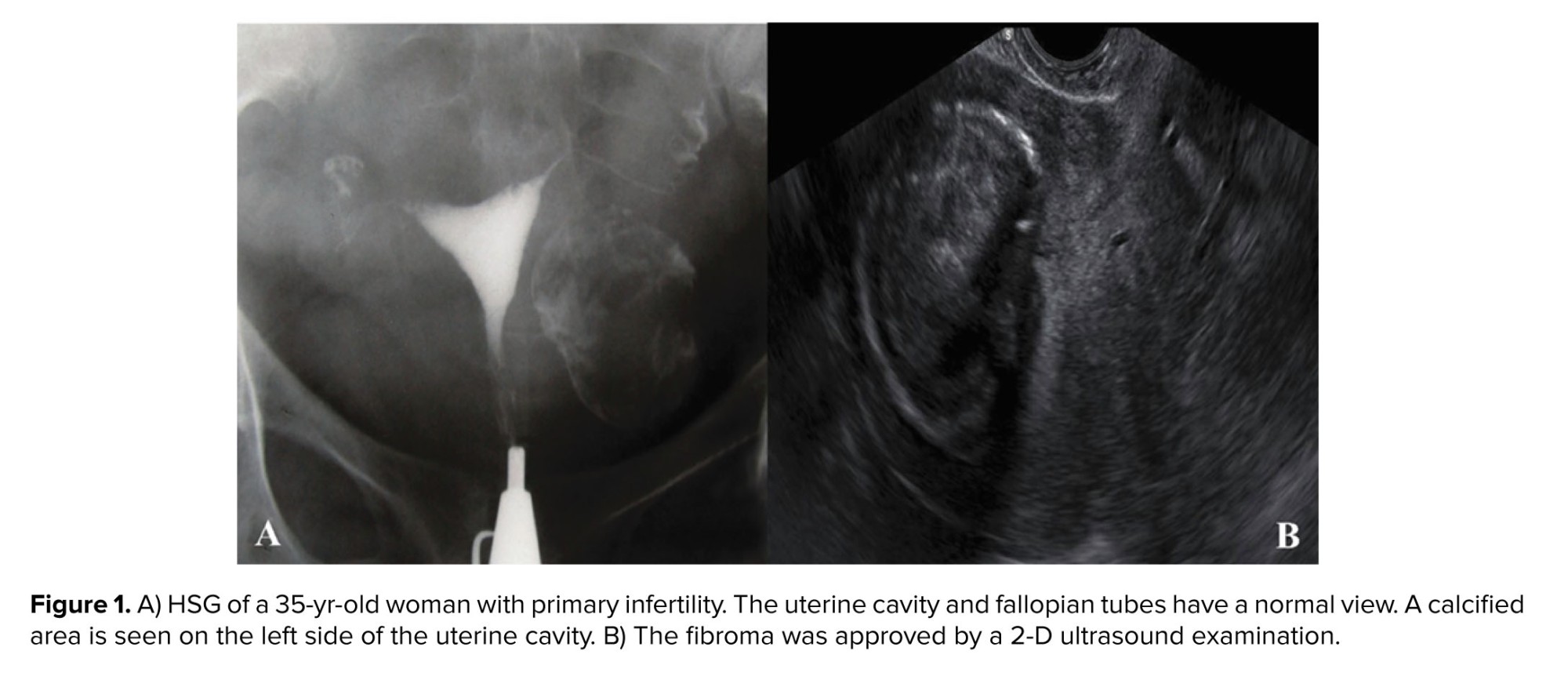

- Calcified fibromas

Uterine leiomyoma would not be detected on plain radiography unless the tumor has undergone calcified degeneration (9). This condition emerges as benign uterine masses with “mulberry” calcification patterns or a cyst wall appearing as rounded structures of varying sizes and locations (10) (Figure 1). Irregular coarse calcifications usually happen with subserosal leiomyomas, especially in tumors with pedicles (9).

- Calcified ovarian fibromas

These calcified pelvic masses are rare tumors, but they may undergo dense calcifications. Ultrasound is required to rule out uterine fibroids and ovarian fibromas (11).

- Calcified ovarian tumor

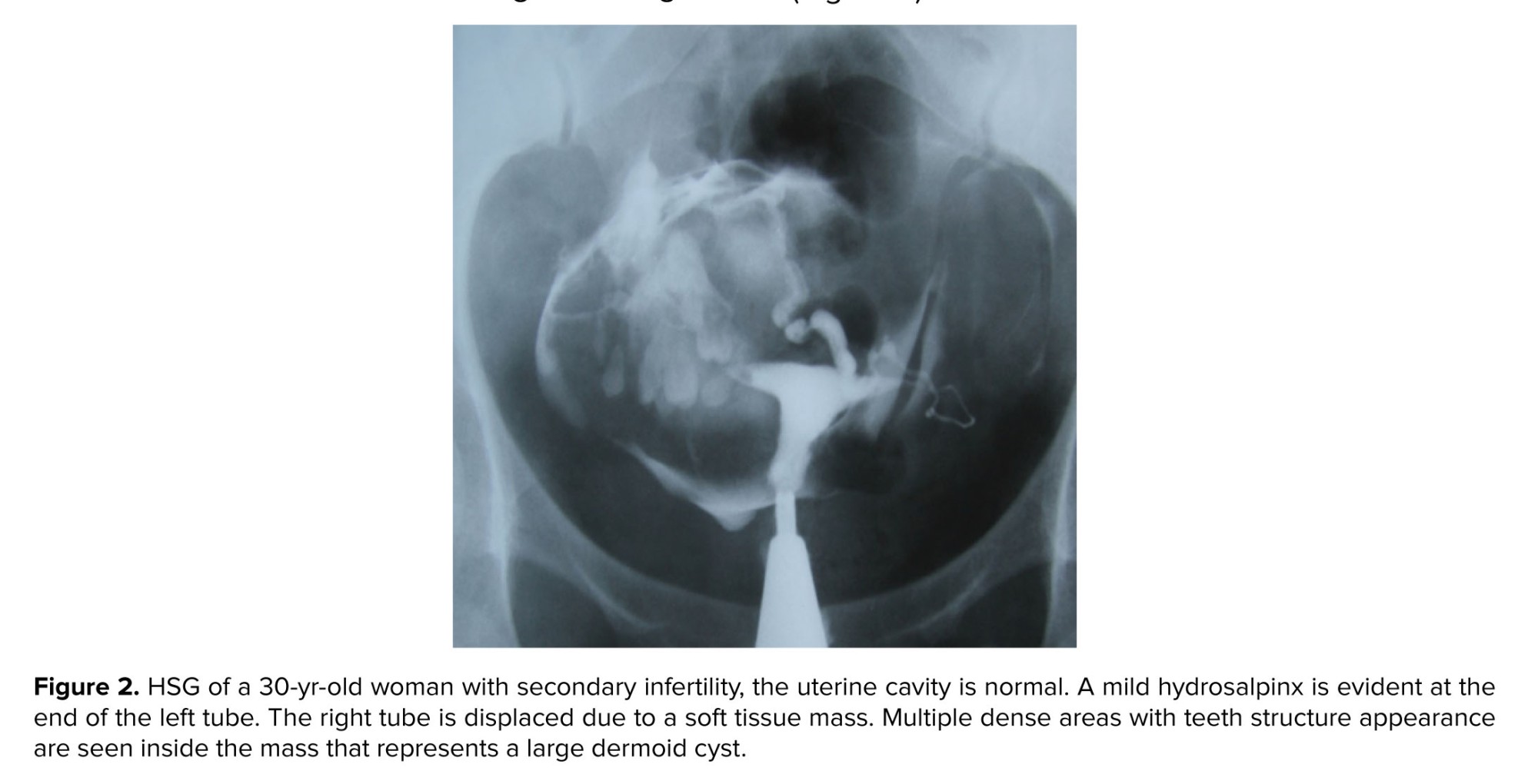

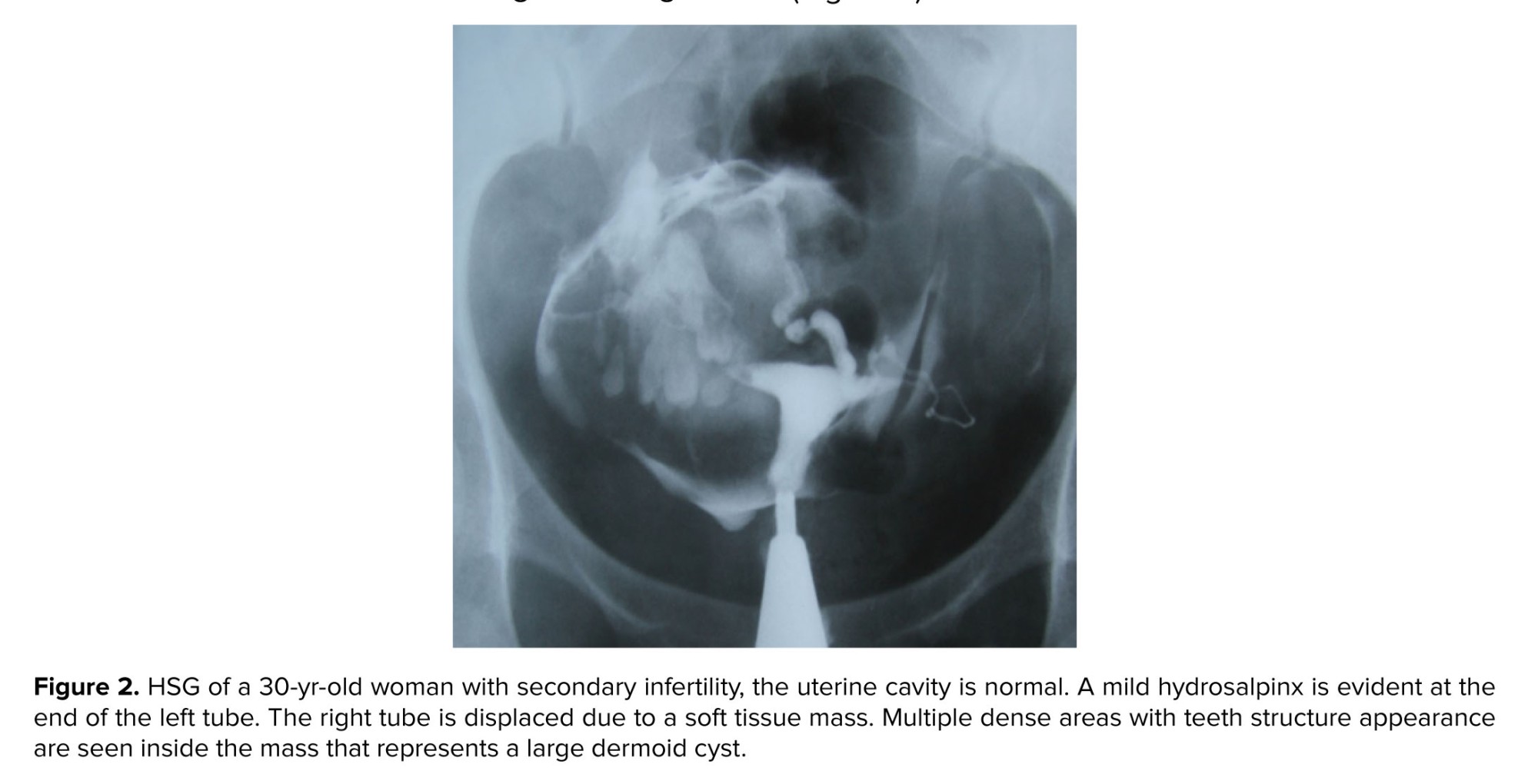

Ovarian calcification may have no specific cause or be associated with benign or malignant conditions such as endometriosis, serous neoplasms, mucinous lesions, teratoma, etc. One of the most common causes of ovarian calcification is dermoid cysts. Dermoid cysts emerge as high-density structures and the most prevalent ovarian tumors originate from primitive germ cell lines and contain hair, teeth, or nerves (Figure 2).

- Calcified fallopian tubes

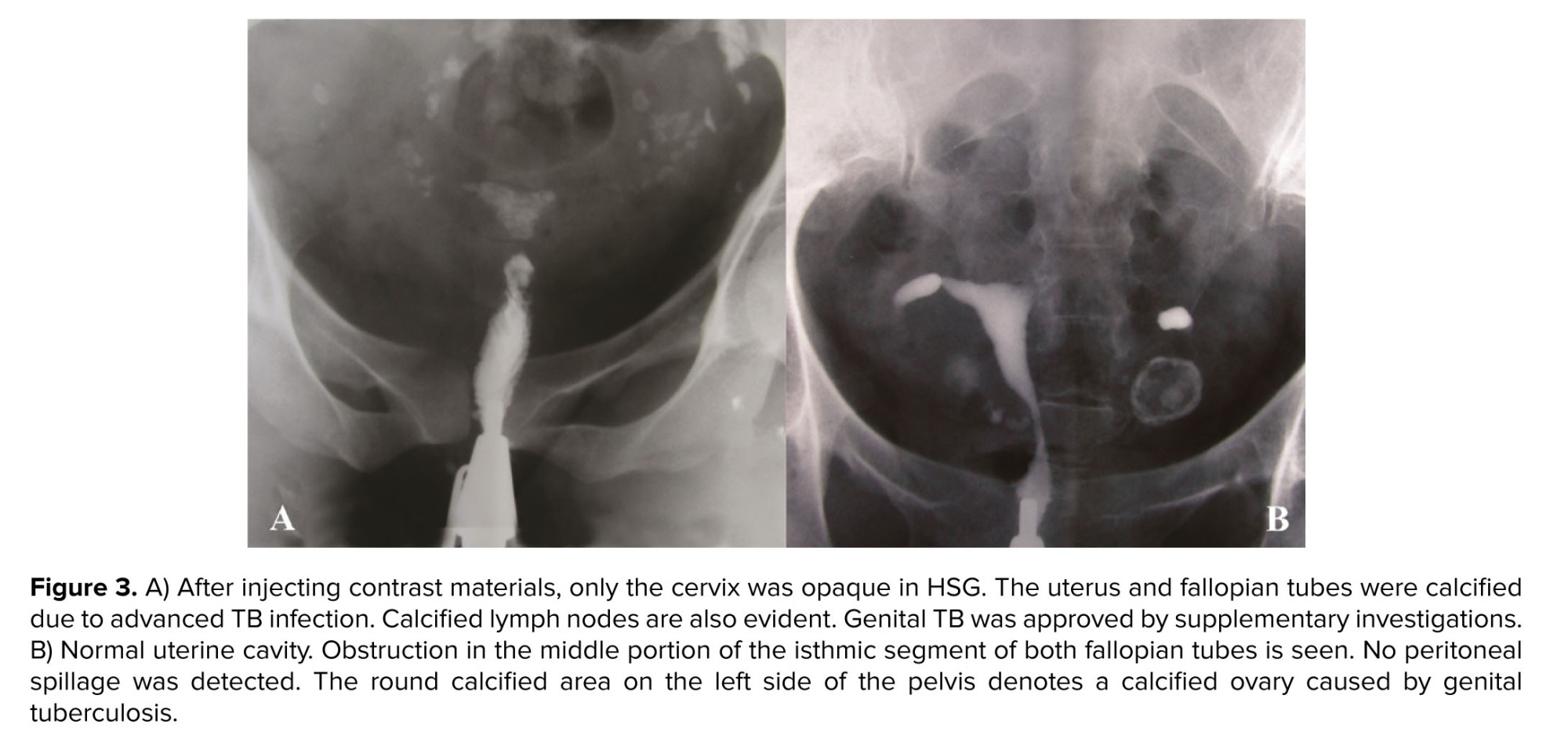

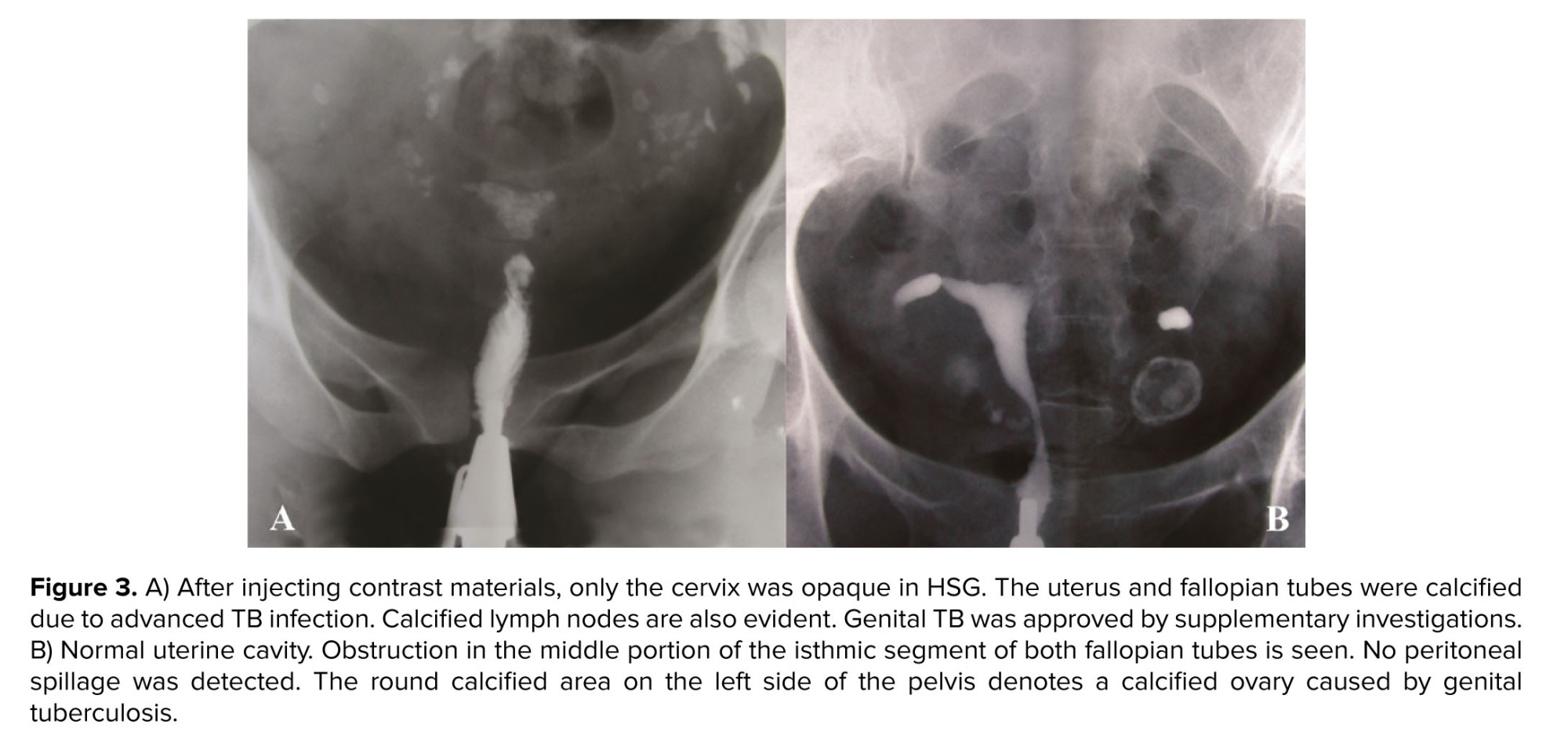

Secondary to tuberculosis: genital tuberculous can cause the calcification of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. The obstruction of the fallopian tubes might occur secondary to this pathology that is mostly bilateral (12) (Figure 3). Tubal calcification can take the form of linear streaks that lie in the course of the fallopian tube or may be seen as faint or dense tiny nodules. Tubal calcifications are usually small and may be straight, bent, or curved in shape.

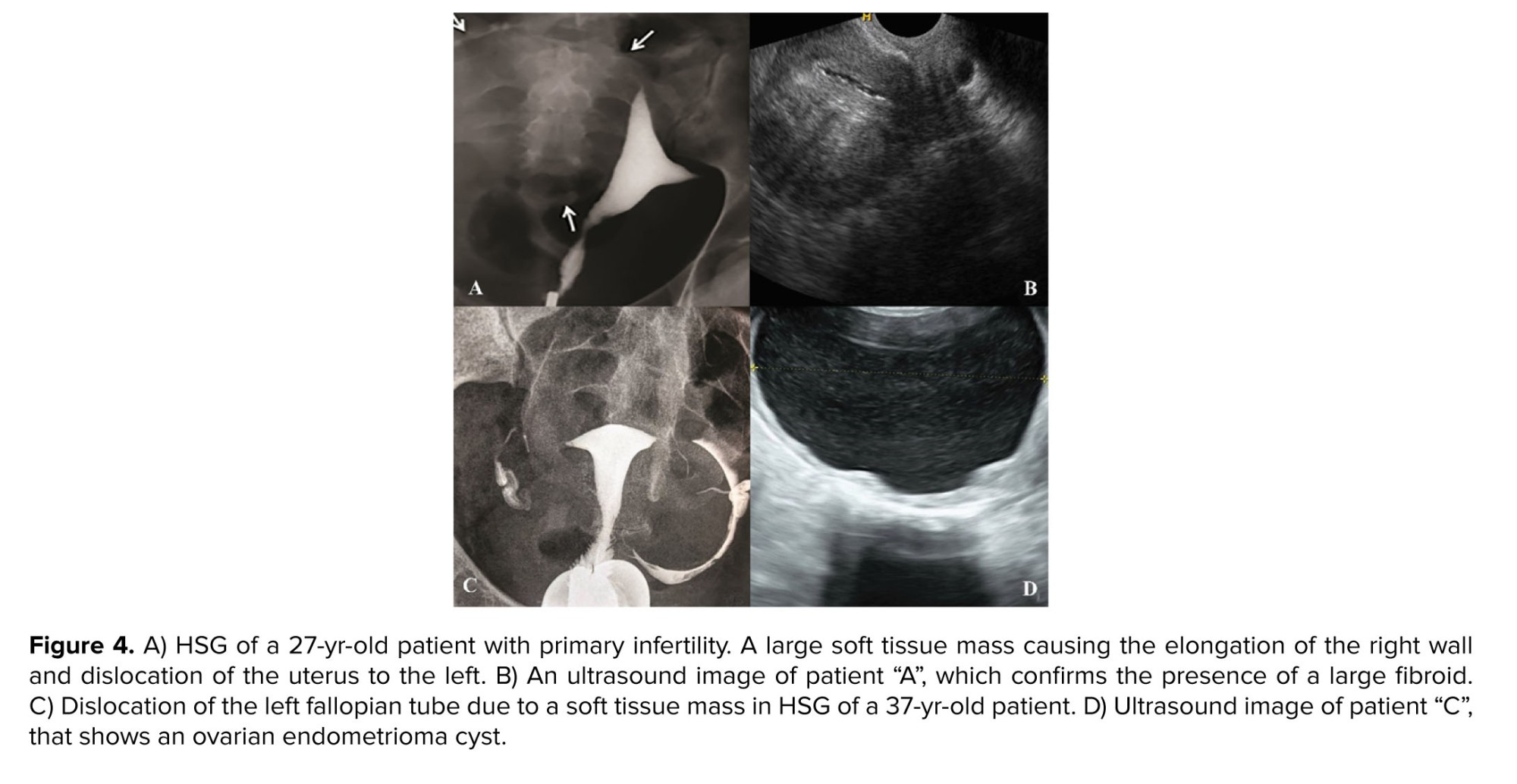

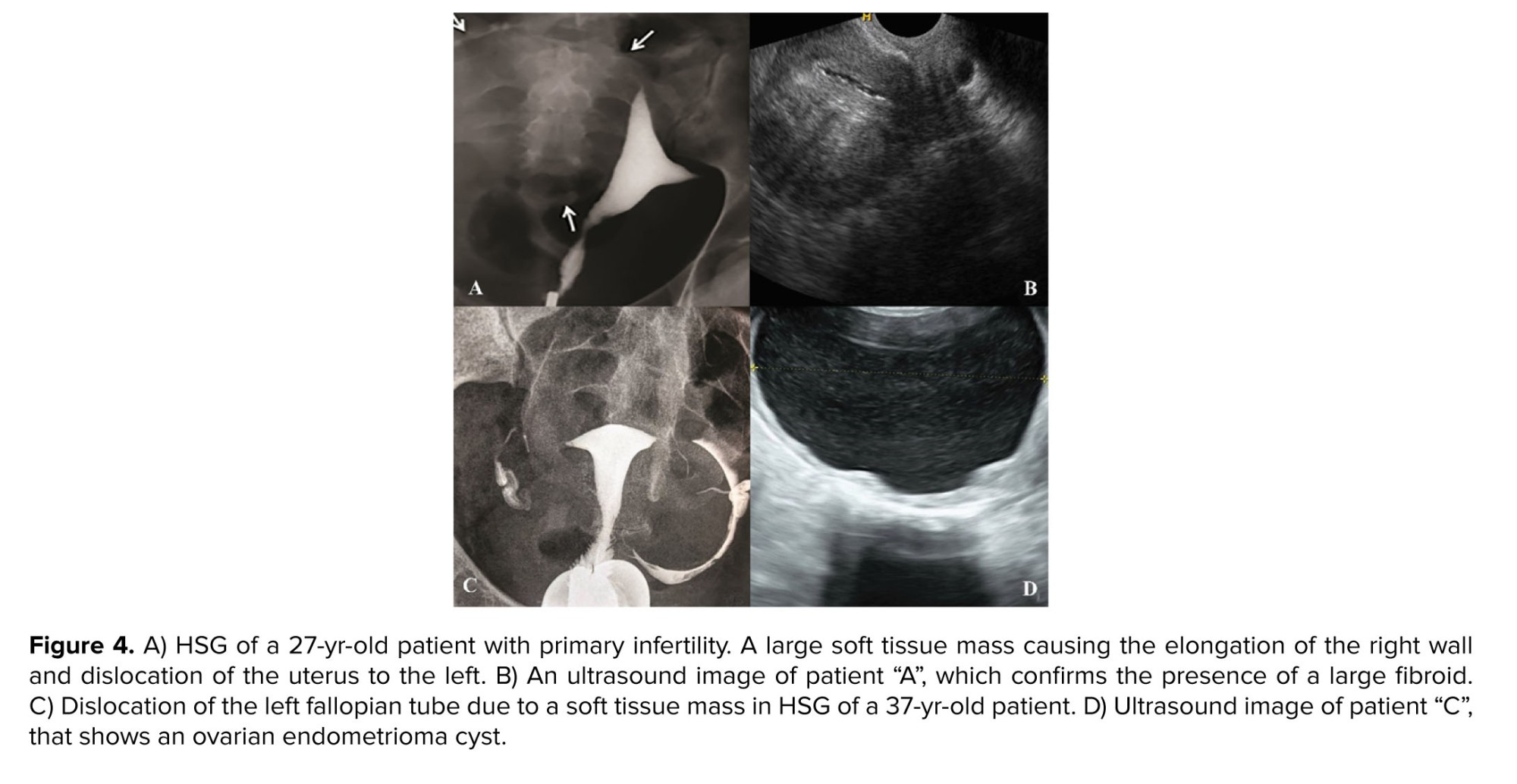

- Soft tissue masses

Frequently, a large soft-tissue mass is detectable in the hysterosalpingogram of the pelvis even if the mass is not calcified. The most common benign tumor of the genital tract which can be seen on a plain pelvic radiograph if it is large, is subserosal leiomyoma. It can be detected due to the distortion, dislocation, or deformation of the uterus and fallopian tubes (Figure 4).

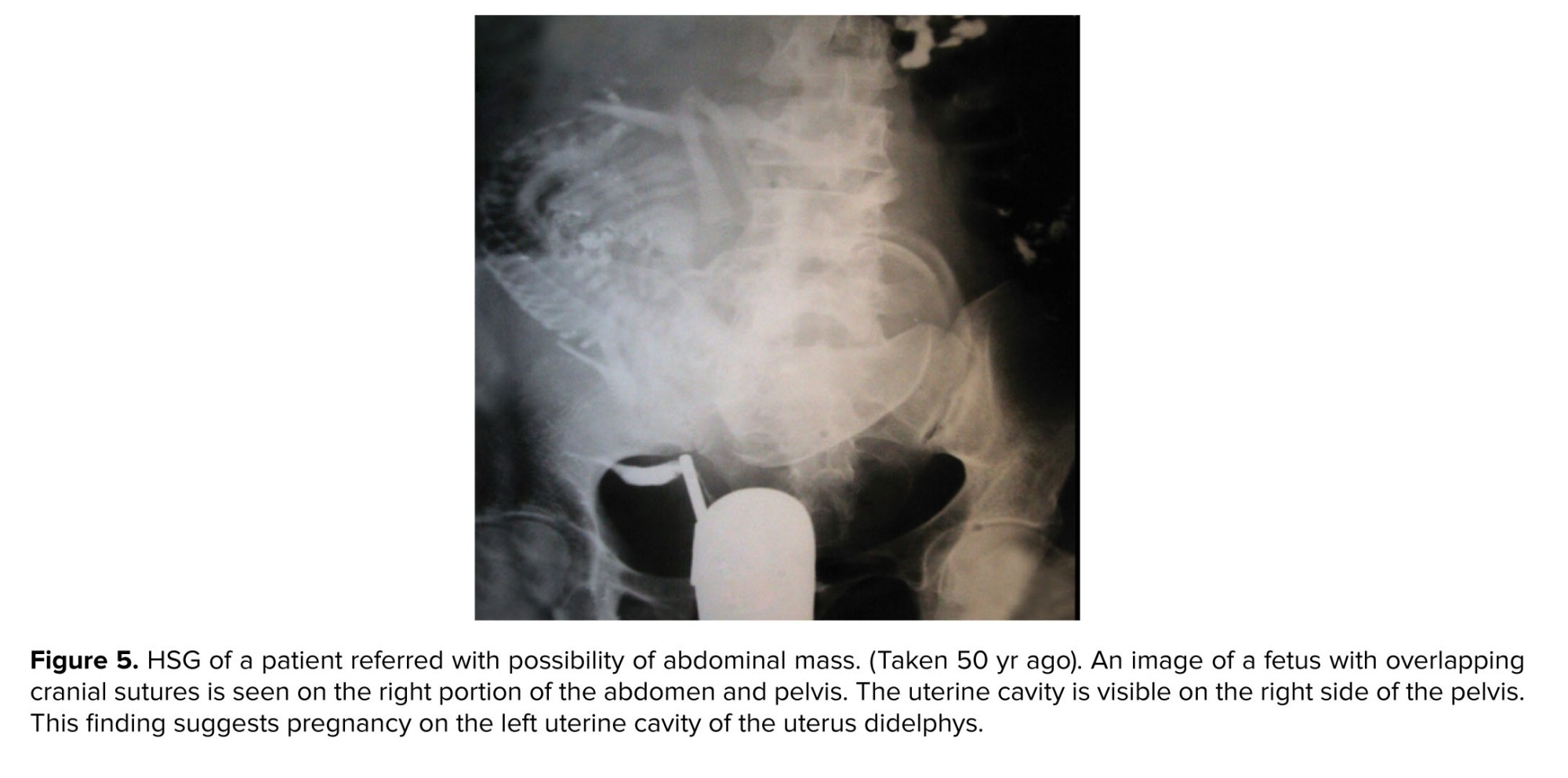

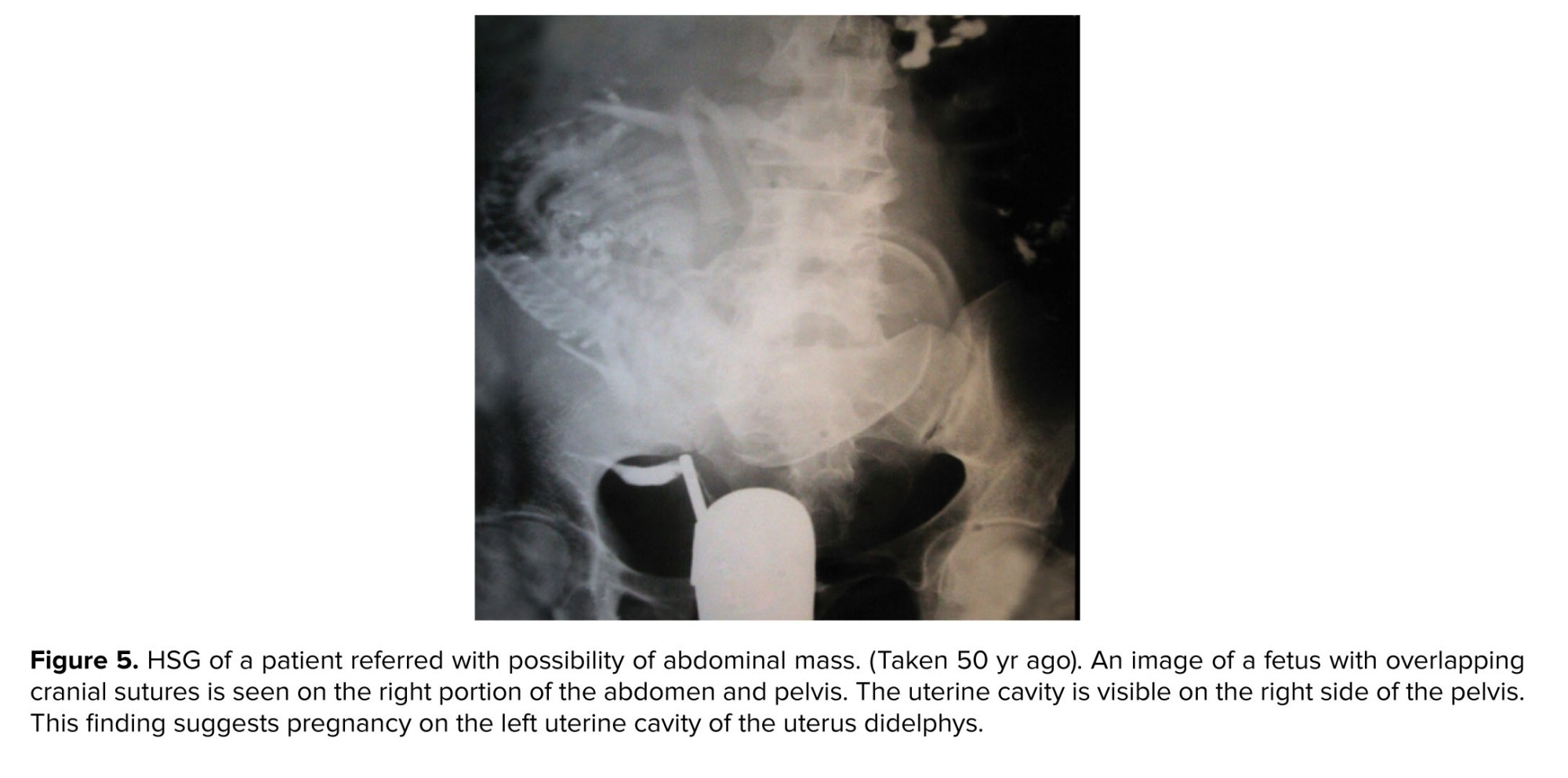

In addition, a few odd and interesting findings might be seen in HSG. Figure 5 shows an astonishing finding of Professor Shahrzad’s old collection. This image was taken 50 yr ago (before the development of ultrasound imaging) to assess abdominal and pelvic mass. The patient was referred to the hospital with a pelvic mass and an HSG had been done.

In addition, a few odd and interesting findings might be seen in HSG. Figure 5 shows an astonishing finding of Professor Shahrzad’s old collection. This image was taken 50 yr ago (before the development of ultrasound imaging) to assess abdominal and pelvic mass. The patient was referred to the hospital with a pelvic mass and an HSG had been done.

-

-

- Non-gynecologic related

-

Particular attention to other pelvic structures is essential to determine the accurate diagnosis. Nongynecologic radiopaque changes in the pelvis can be related to the bowel and urinary tracts or localized to the peritoneal cavity or extraperitoneal pelvic structures (6). These conditions are not common but essential to recognize and distinguish from common gynecologic diseases.

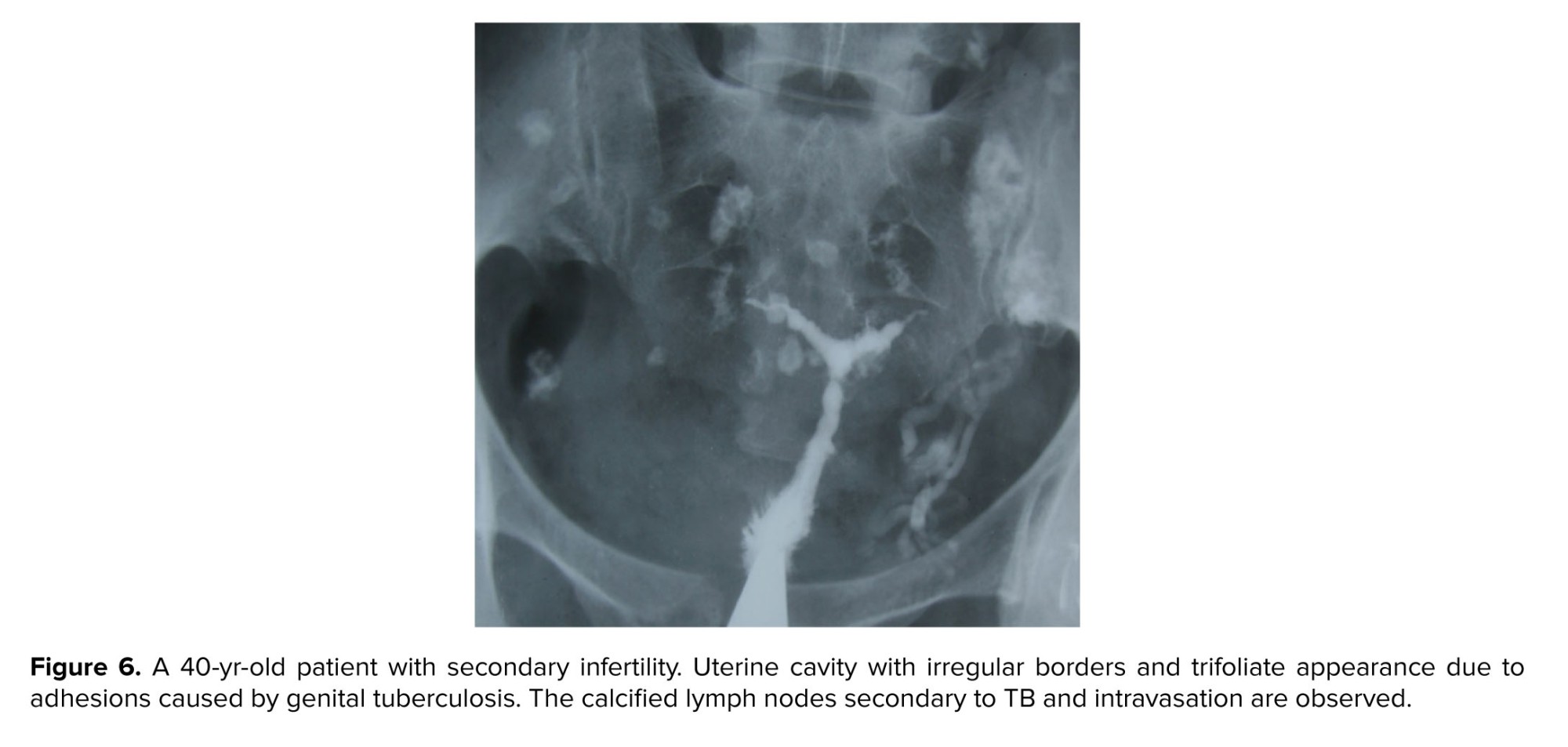

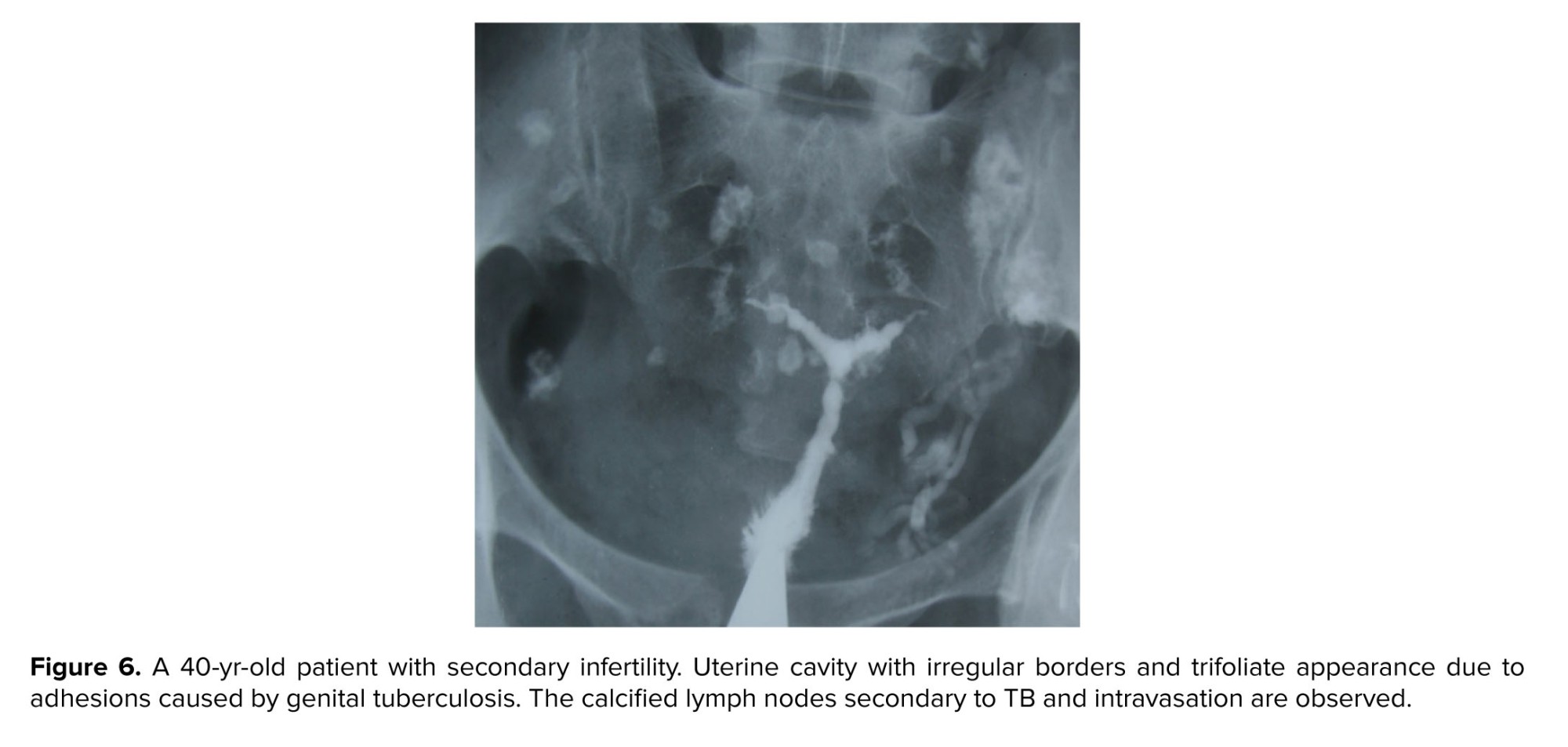

- Calcifications of non-gynecologic organs

Calcified non-gynecologic organs and tissues might emerge as dense areas in HSG. The intestine, urinary system, lymphatic nodes, and vessels can develop calcified areas (13). Calcified mesenteric lymph nodes commonly appear as smooth, oval, and outlined structures in HSG because of infections, including tuberculosis (14) (Figure 6).

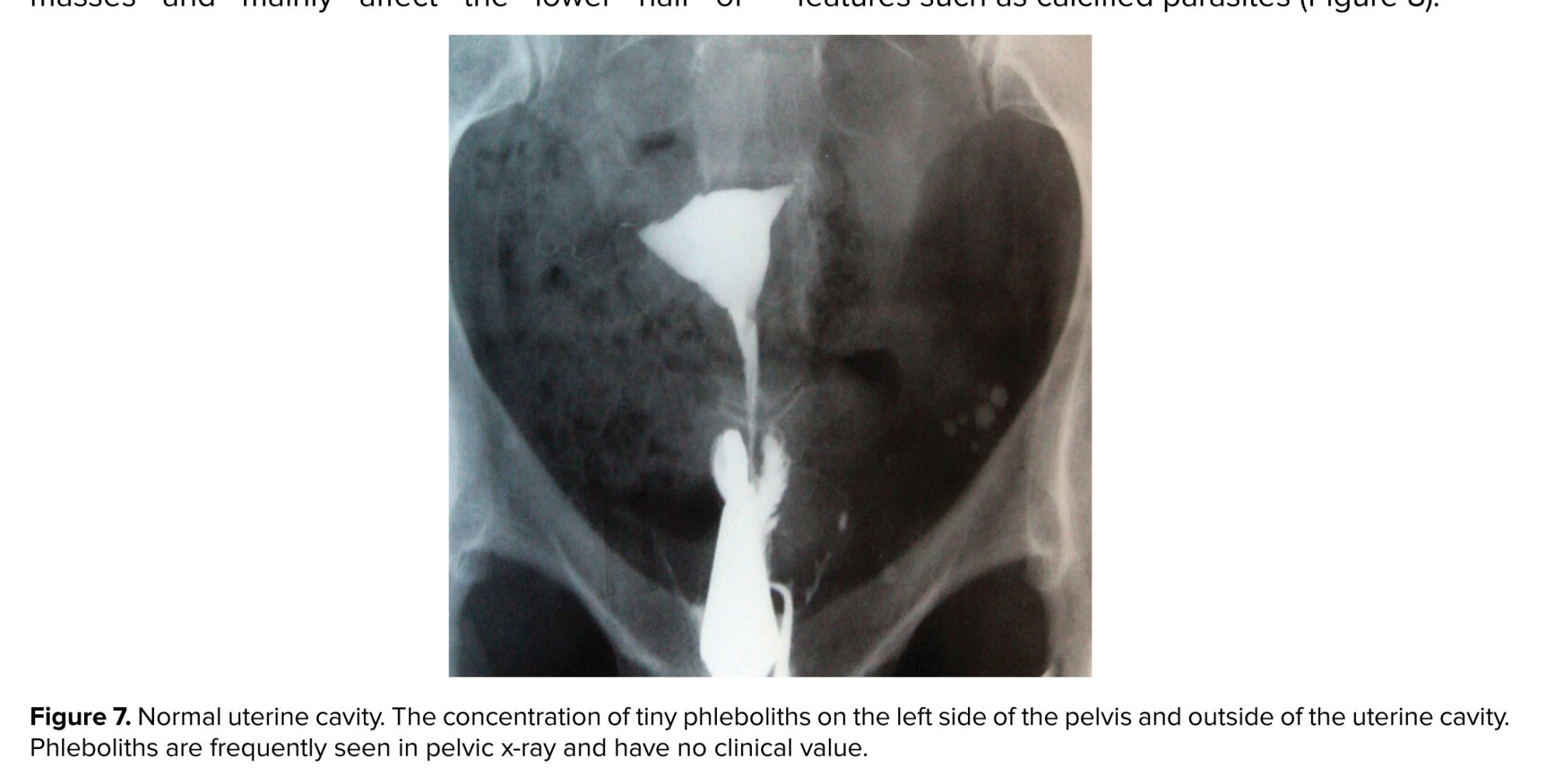

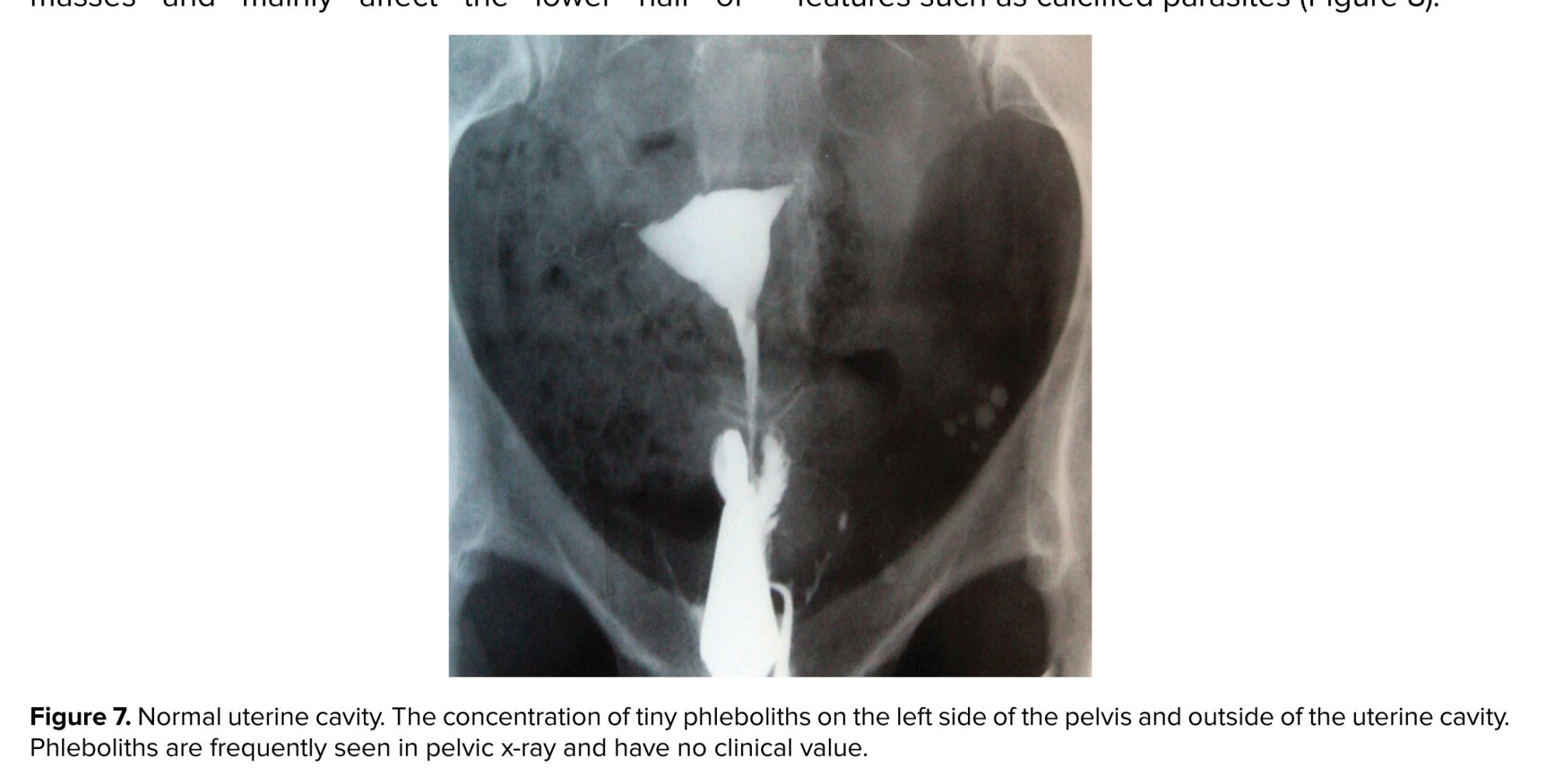

Vascular calcification affects both arteries and veins. Pelvic phleboliths refer to the calcification of veins, emerging as vein stones, develop small, smooth, round, and calcified masses and mainly affect the lower half of the pelvic inlet (7) (Figure 7). As an incidental finding, this condition is of no pathological significance.

The intestine and its content make some distinct features such as calcified parasites (Figure 8).

Vascular calcification affects both arteries and veins. Pelvic phleboliths refer to the calcification of veins, emerging as vein stones, develop small, smooth, round, and calcified masses and mainly affect the lower half of the pelvic inlet (7) (Figure 7). As an incidental finding, this condition is of no pathological significance.

The intestine and its content make some distinct features such as calcified parasites (Figure 8).

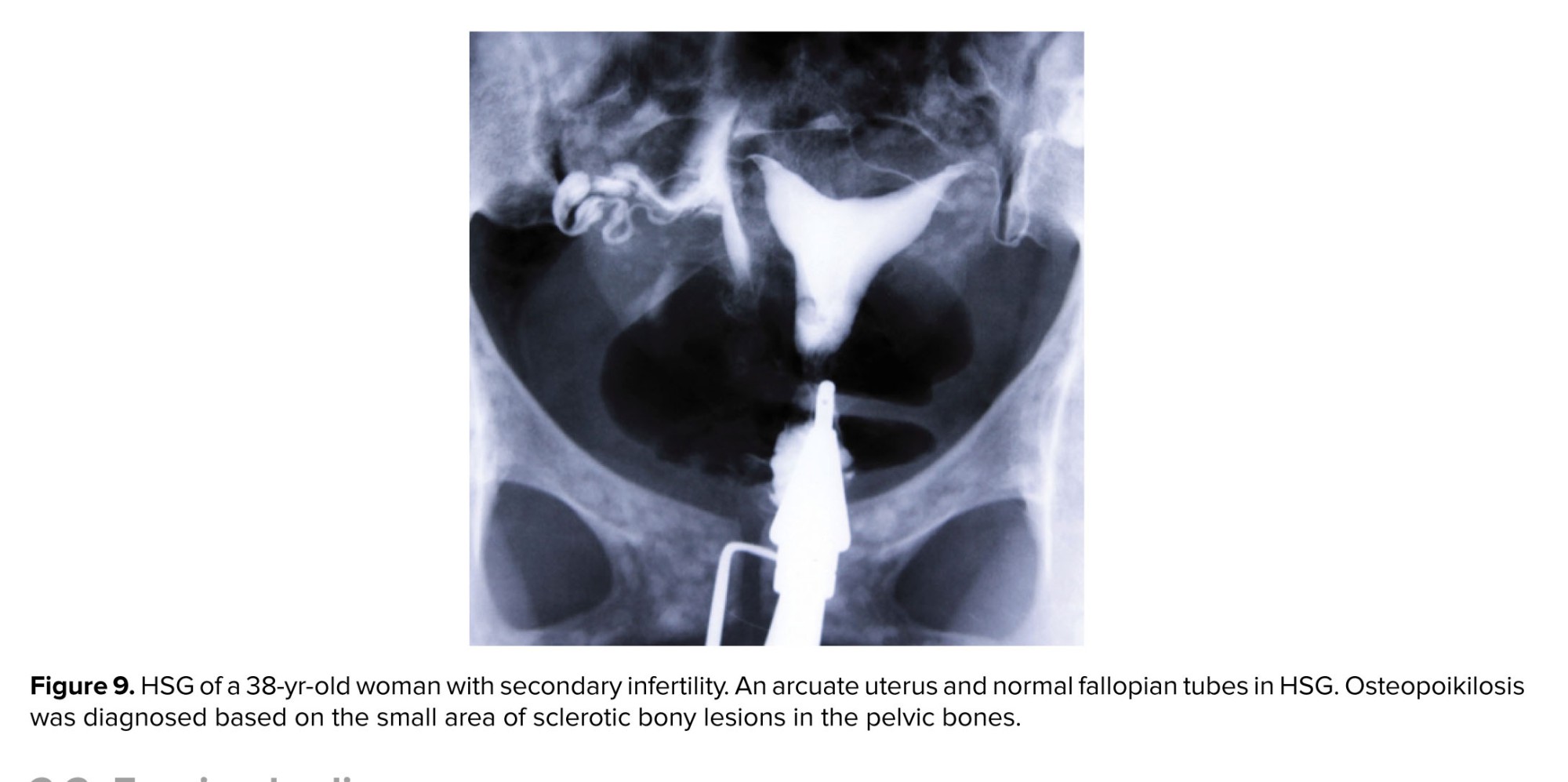

- Pelvic bone anomalies

Bone lesions include damaged areas of bone due to infections, fractures, cysts, and tumors. Most bone lesions are benign. These lesions and diseases of bone tissue can be reflected in HSG. Therefore, assessment of bone tissue is necessary when an HSG cliché is reported (Figure 9).

-

- Foreign bodies

Retained radiopaque foreign bodies appearing in or out of the body in HSG are categorized as intra-pelvic foreign bodies or external bodies. Depending on the anatomical location, type of material, and size of the object, they may affect the evaluation of the intrapelvic organs.

-

-

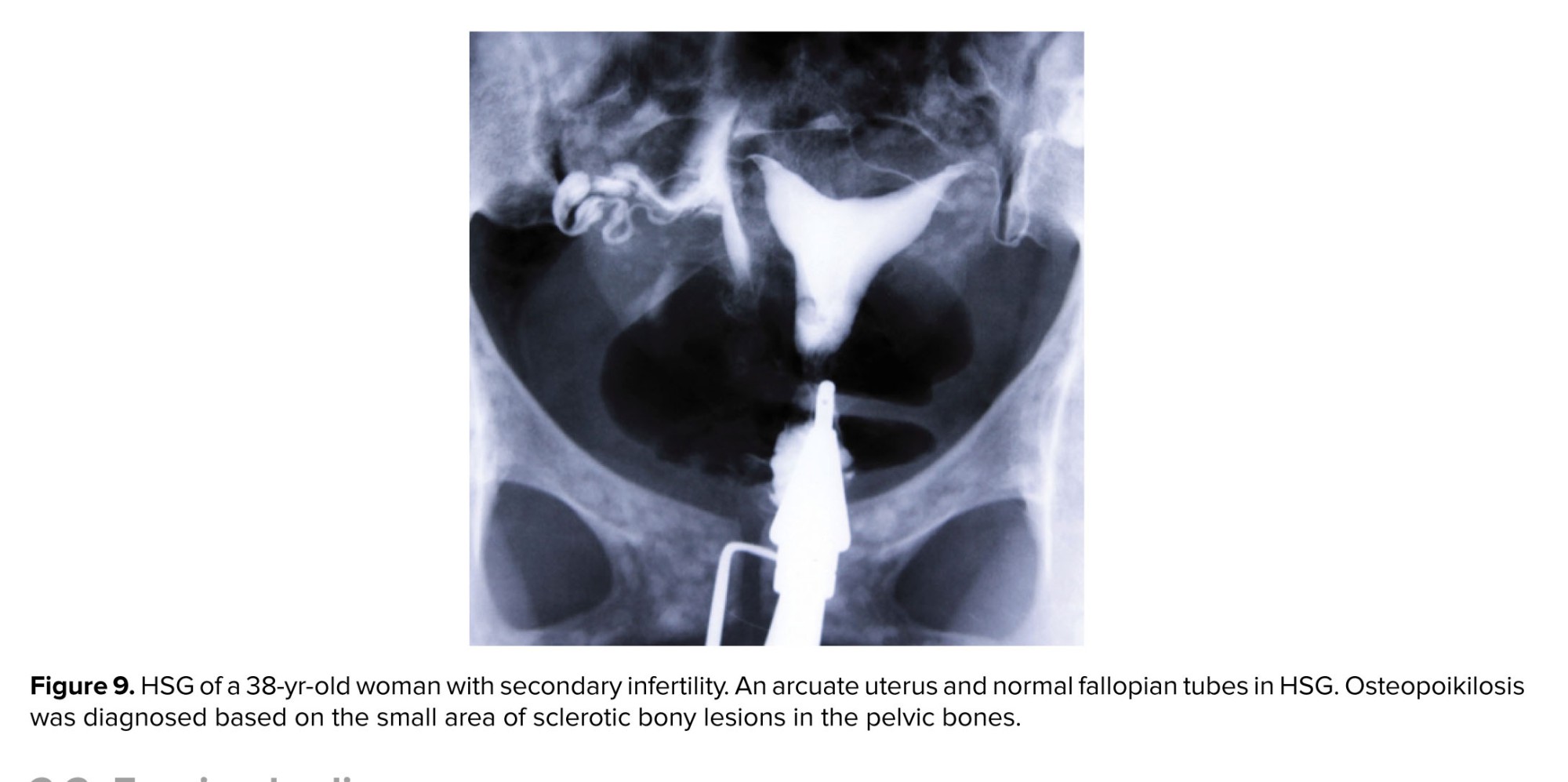

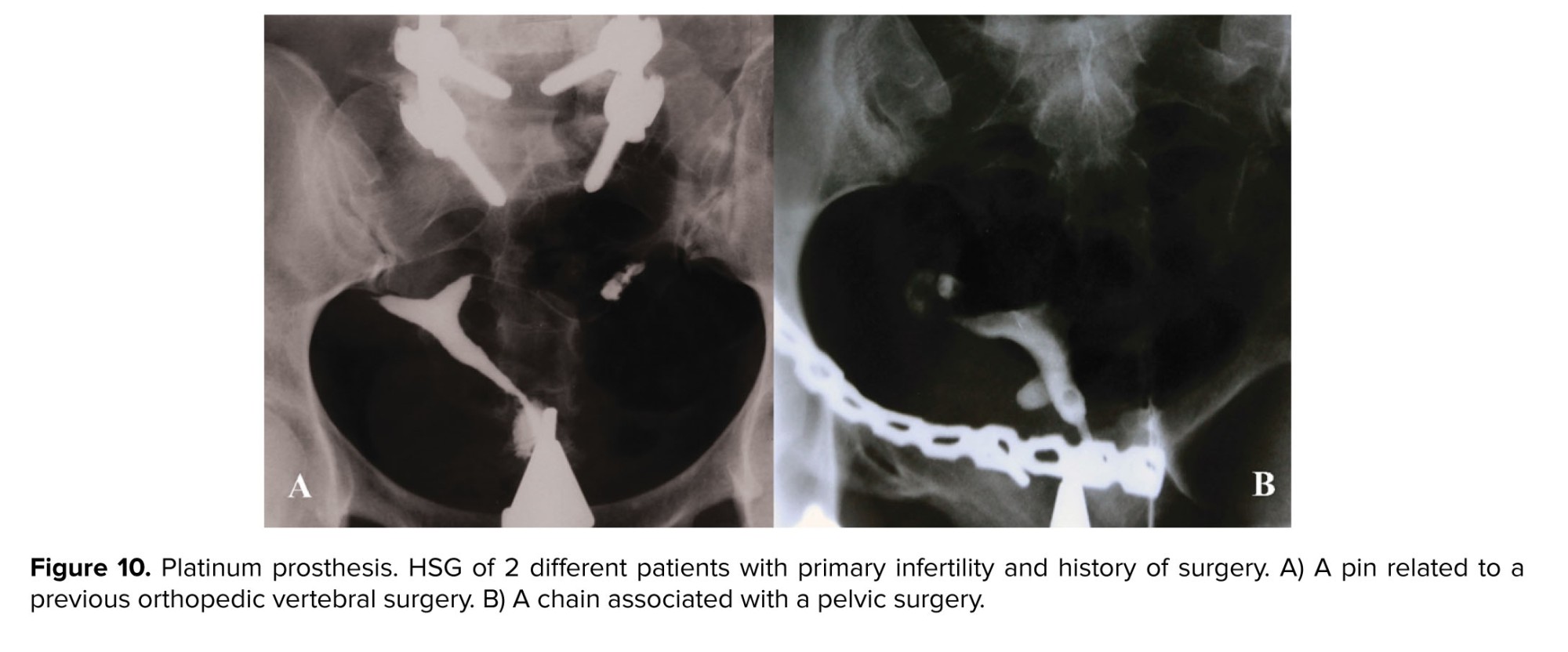

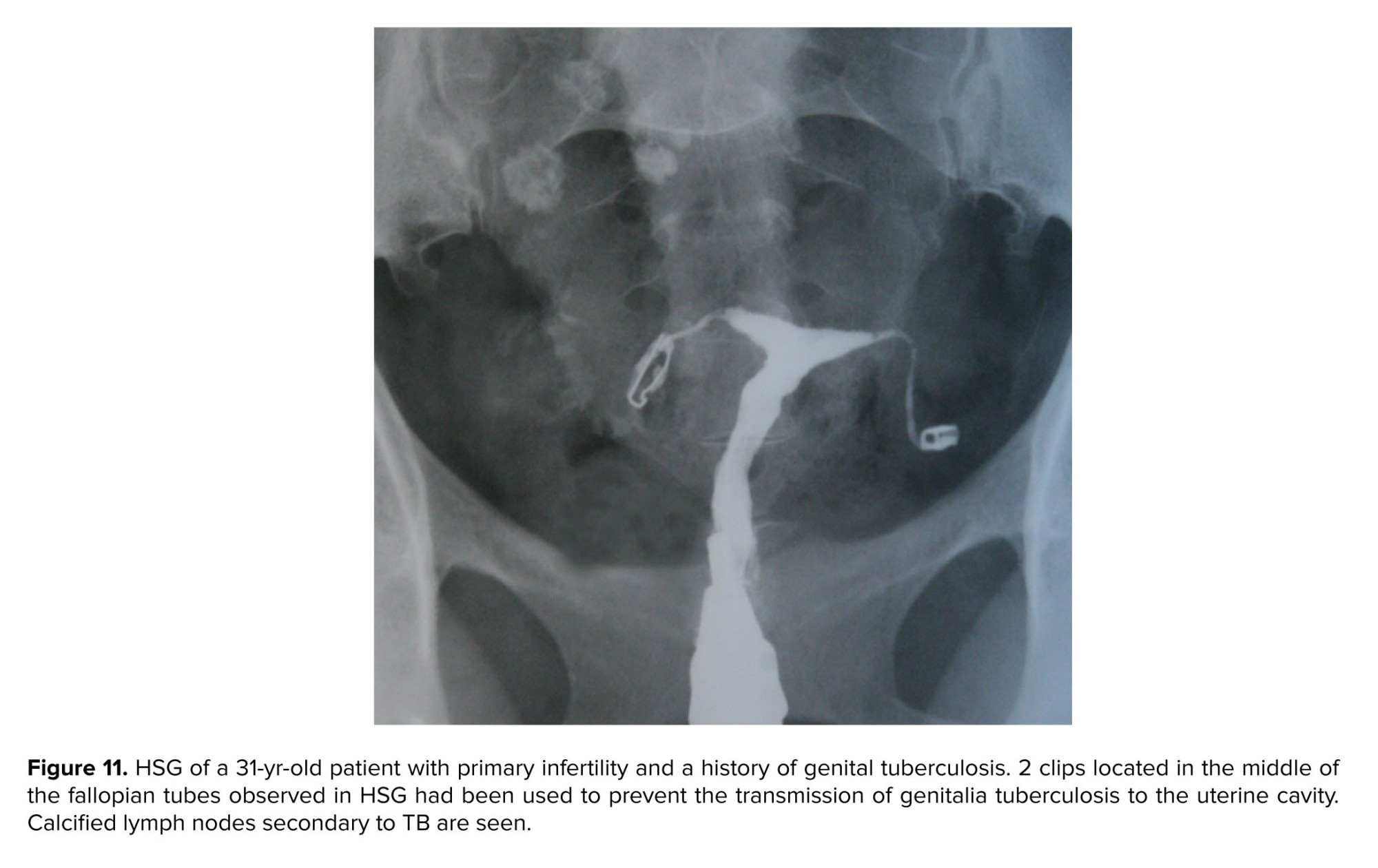

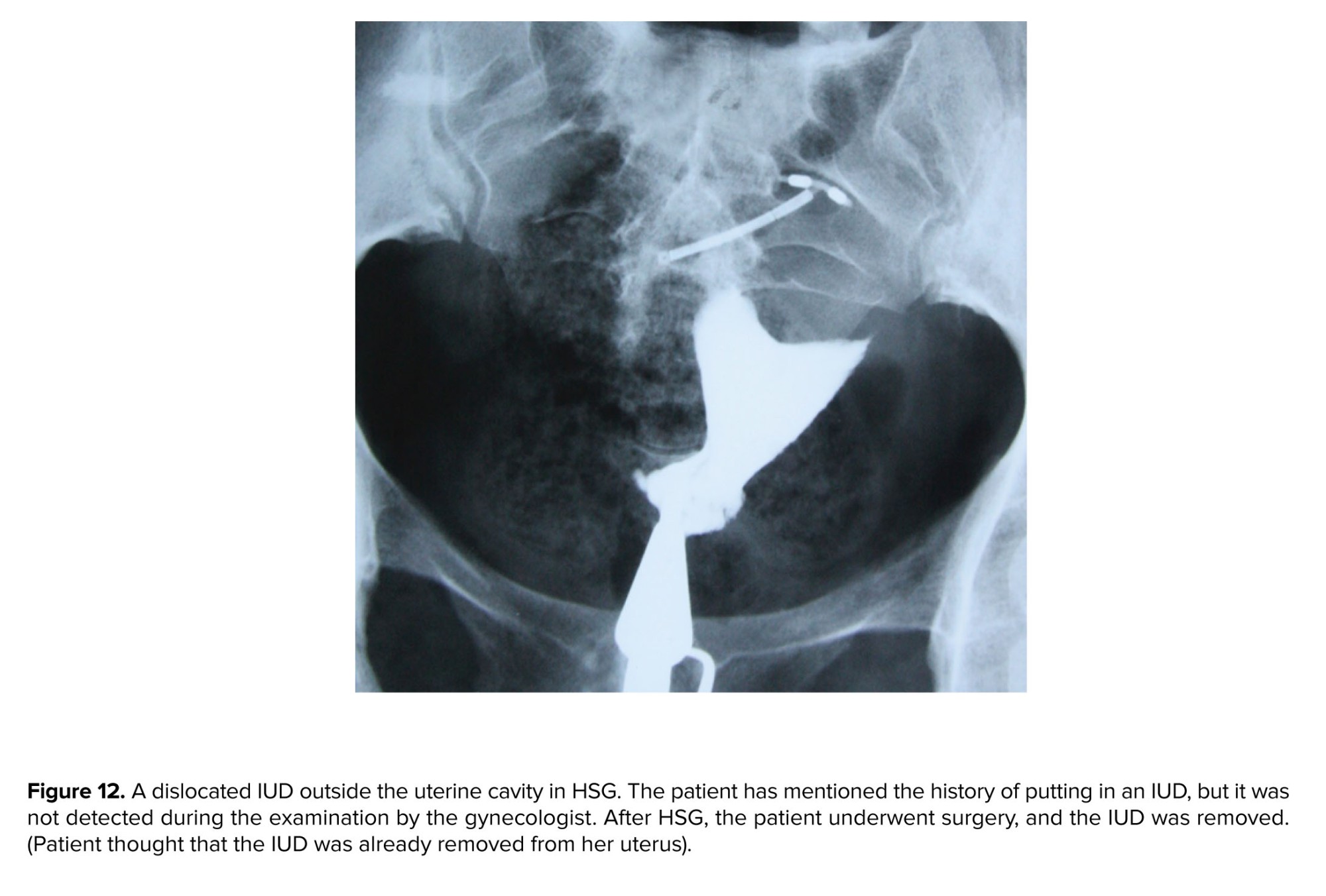

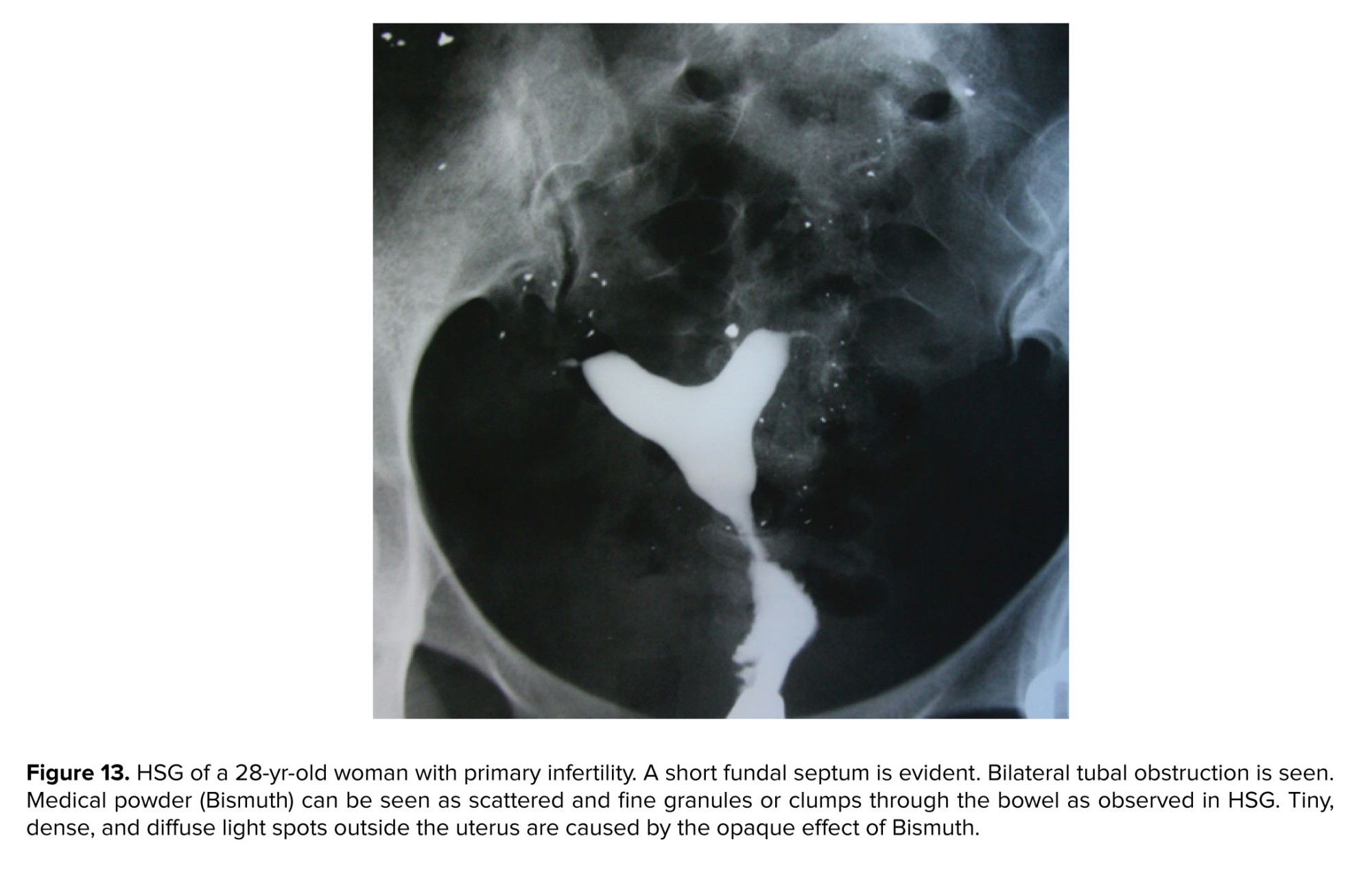

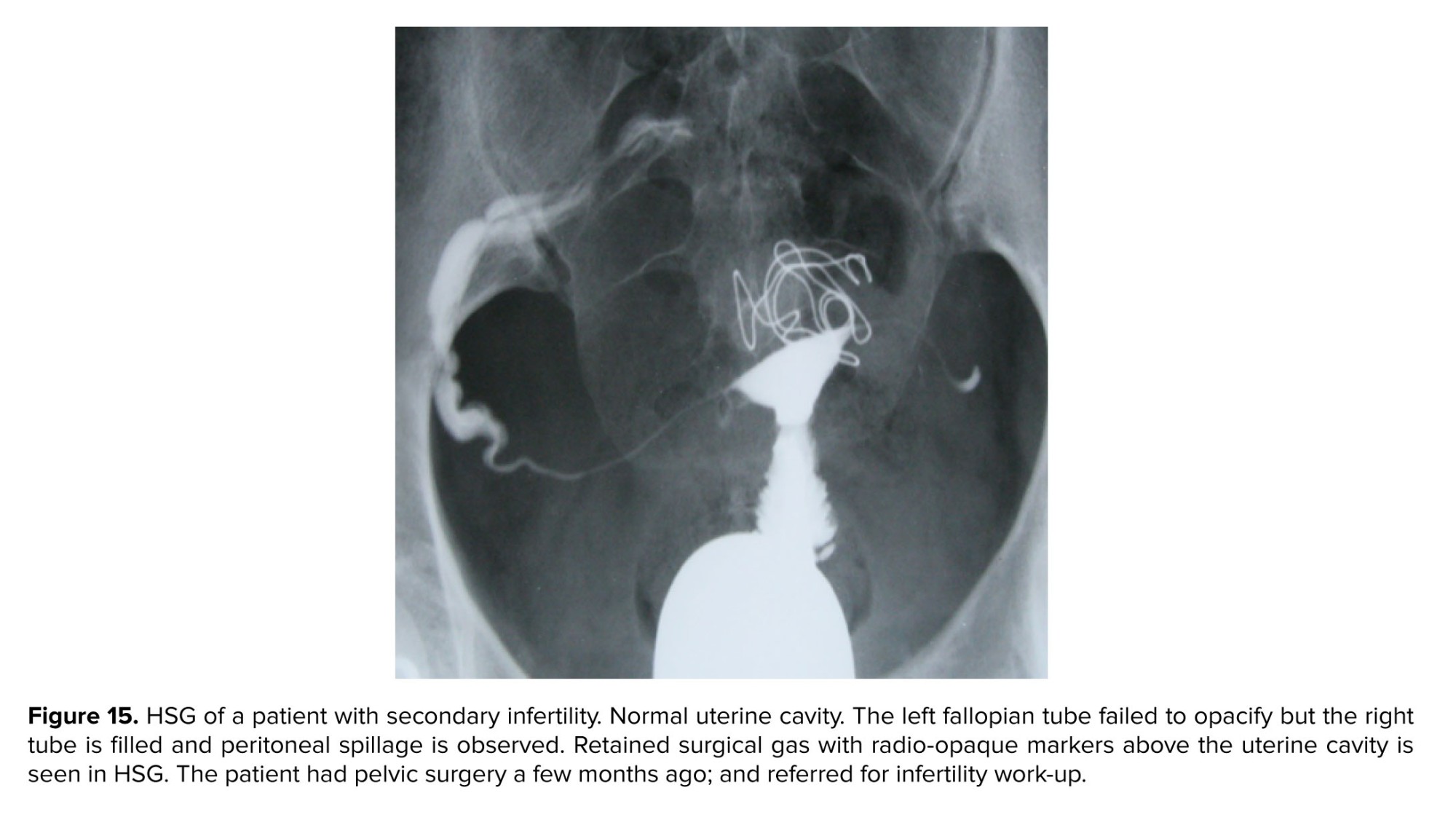

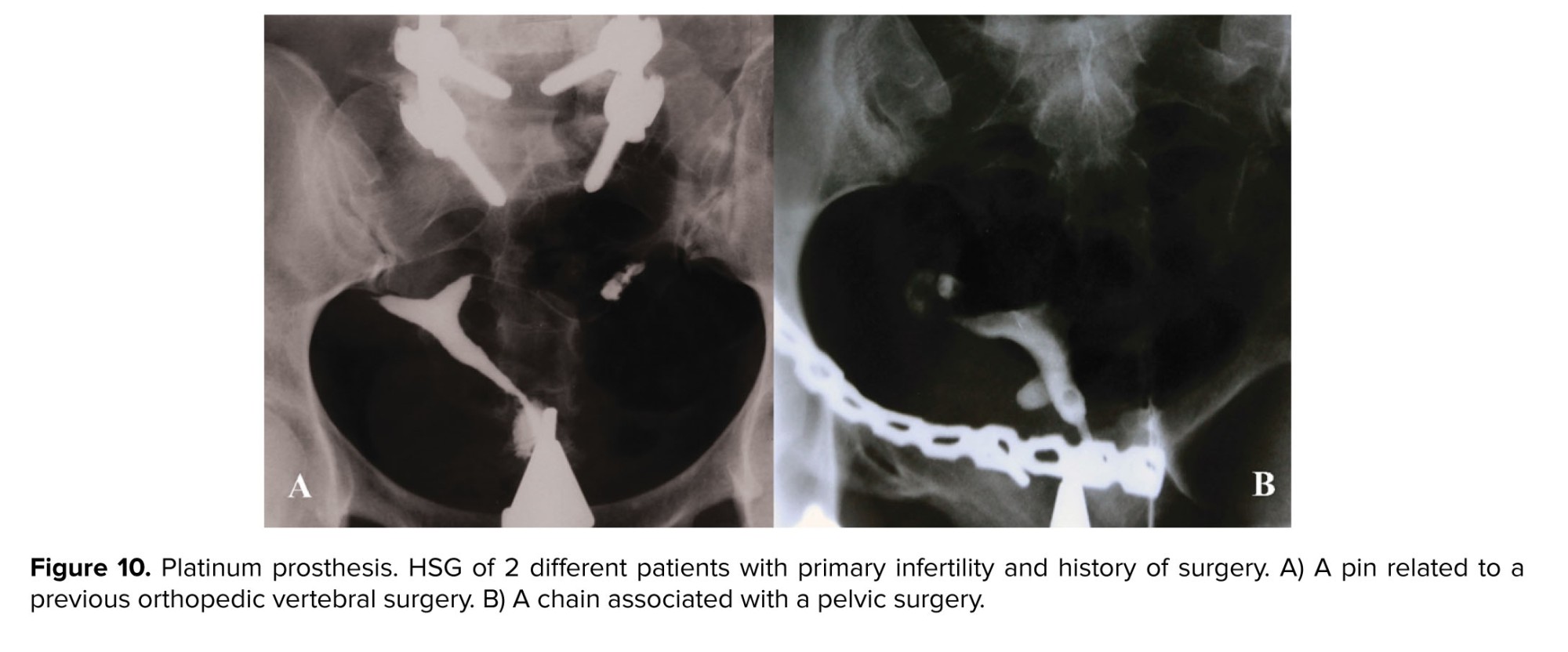

- Intra-pelvic foreign bodies

-

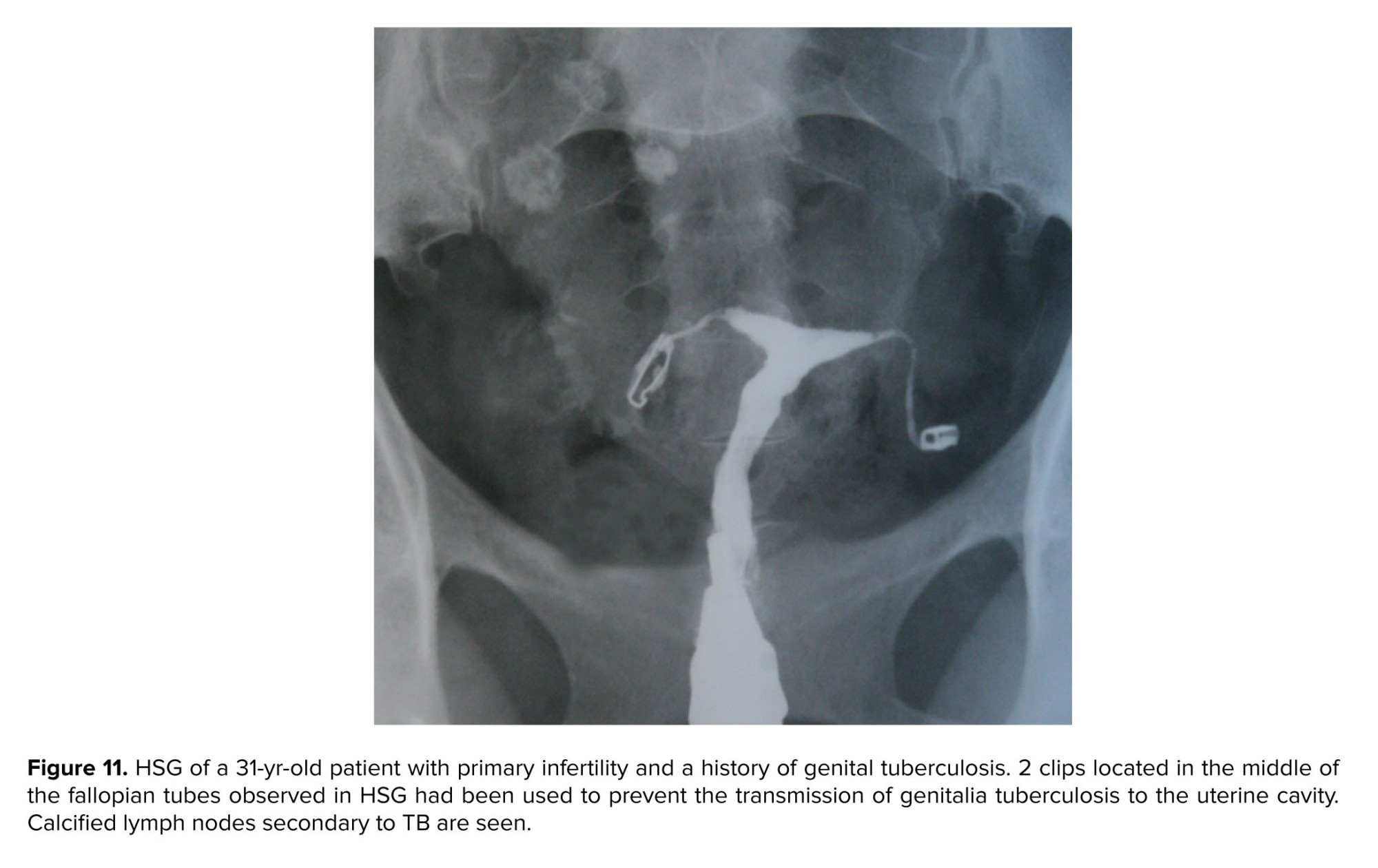

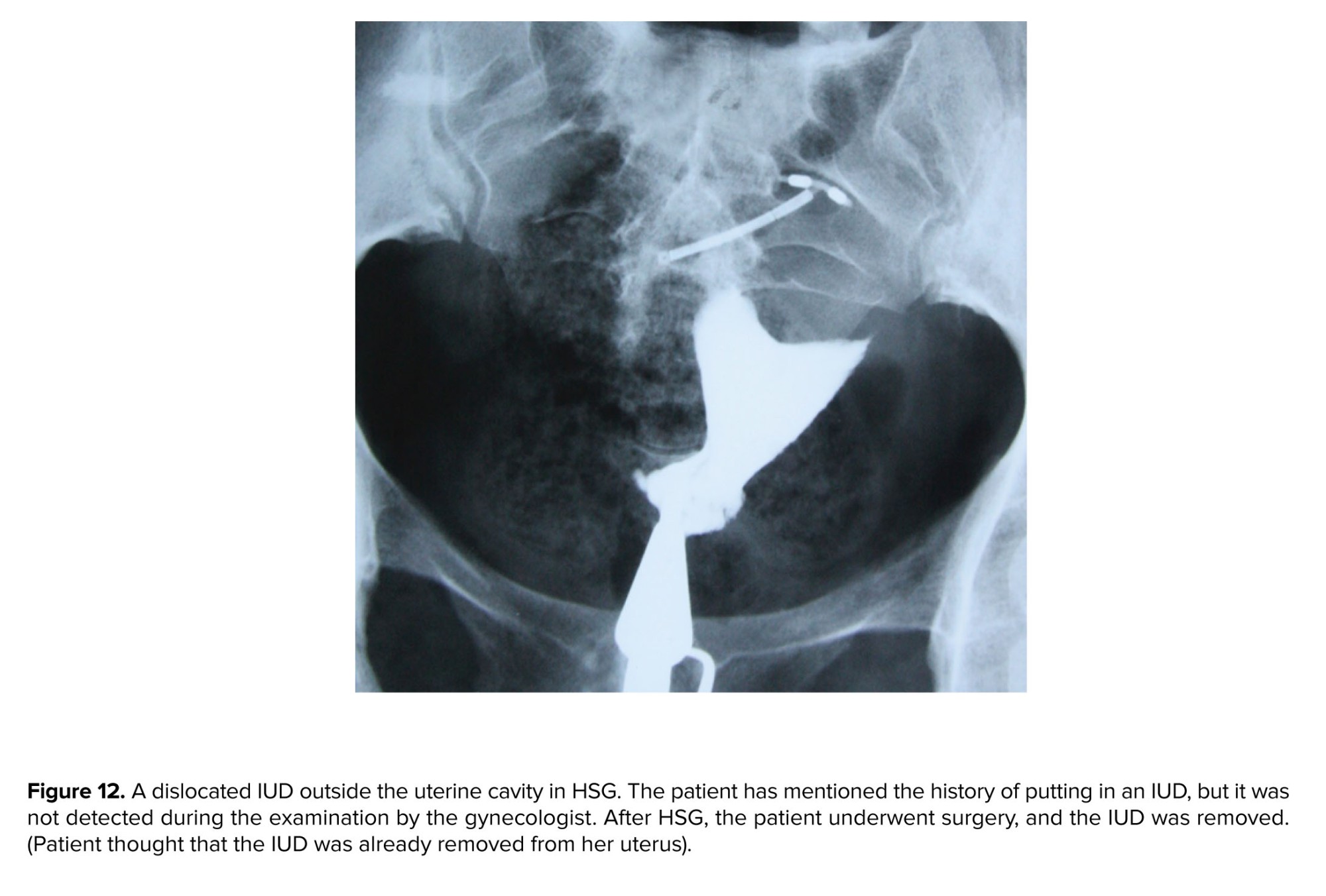

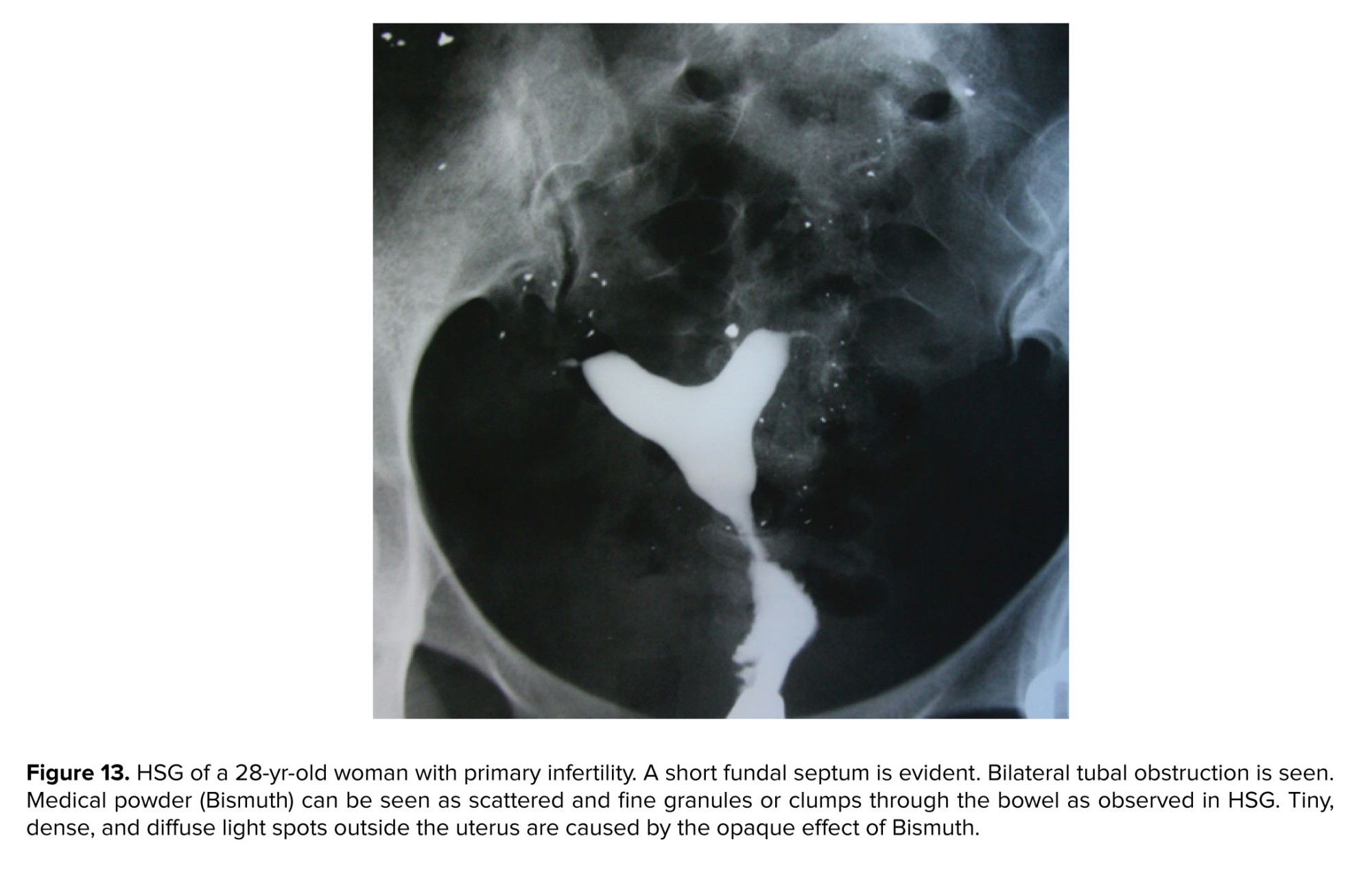

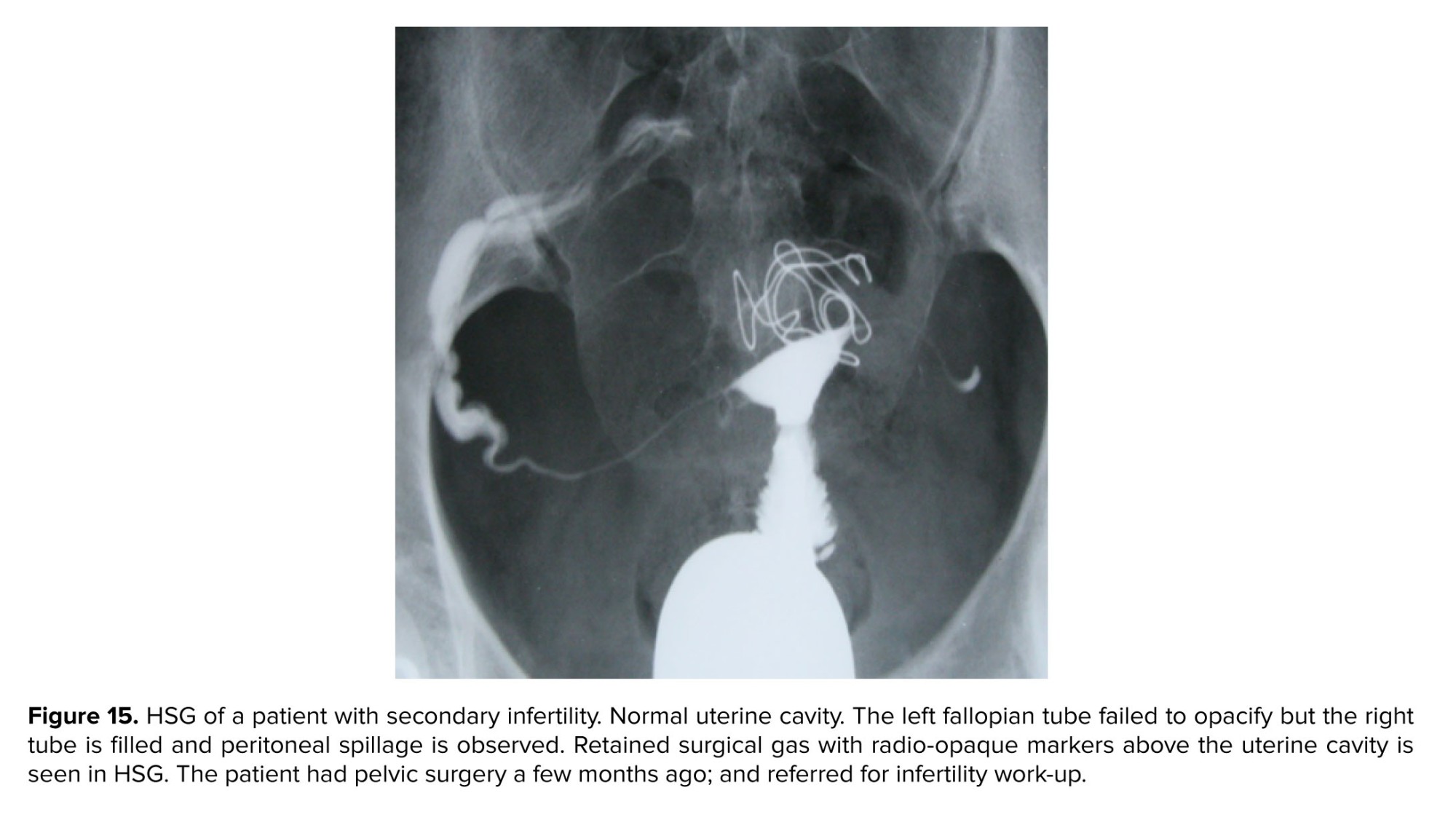

The radiopaque objects originating in the external environment may be introduced into the pelvic area through different ways. Intra-pelvic foreign bodies such as platinum prostheses, clips, dislocated IUD, drugs, needles, and retained surgical instruments or surgical packs can be medically located or inadvertently left in the pelvis by medical staff or be swallowed. The term "gossypiboma'' or "textiloma" refers to a foreign object that is inadvertently left in body cavities after surgical operations. This condition is uncommon but not rare surgical error. Surgical instruments and devices are apparent in plain film because of the characteristic appearance of radiopaque tape or wires of laparotomy pads and surgical sponges, respectively. The retained surgical sponge may cause complications such as abdominal pains, nausea, vomiting, features of intestinal obstruction, or malabsorption syndrome (Figures 10-15).

-

-

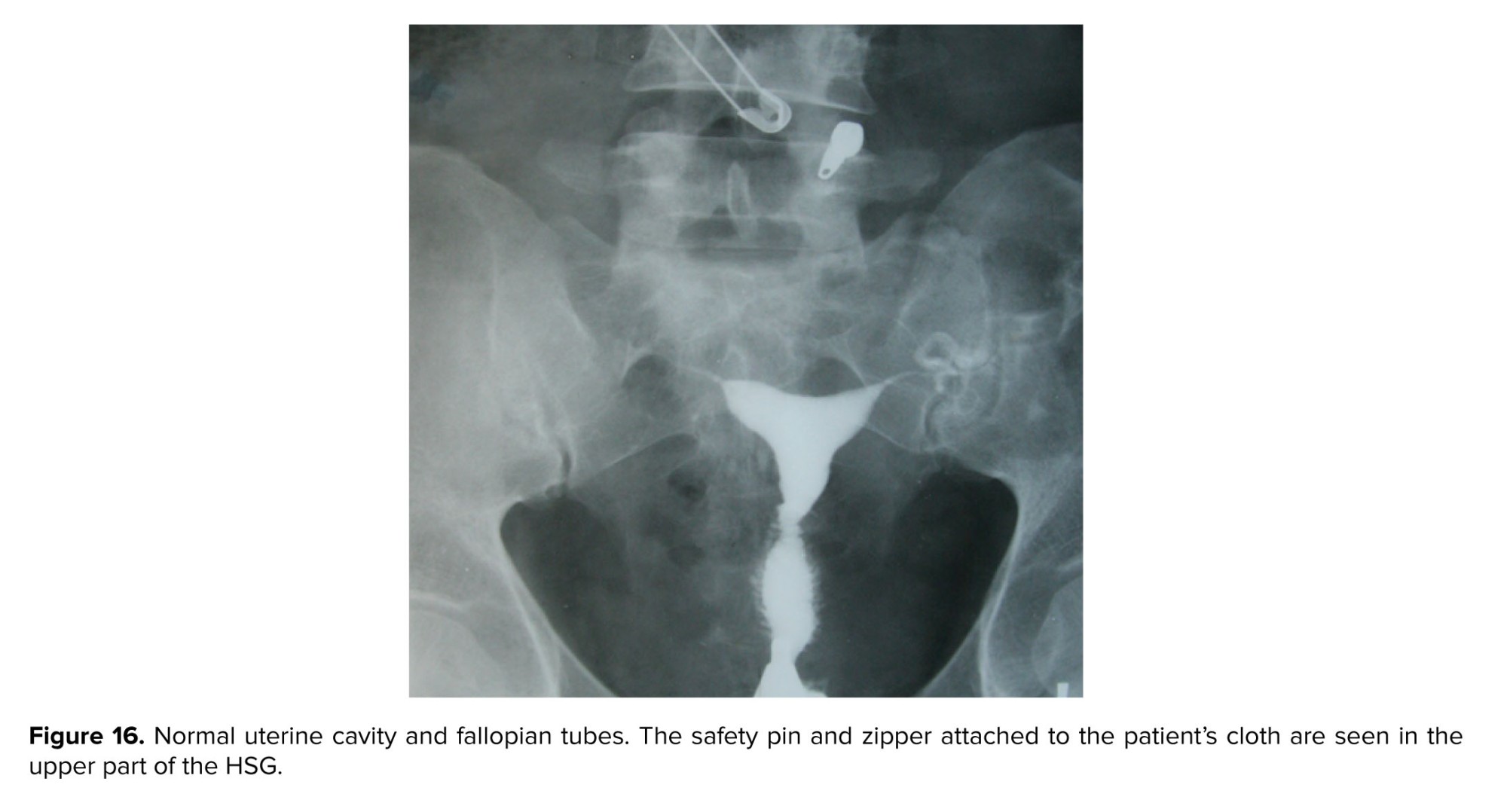

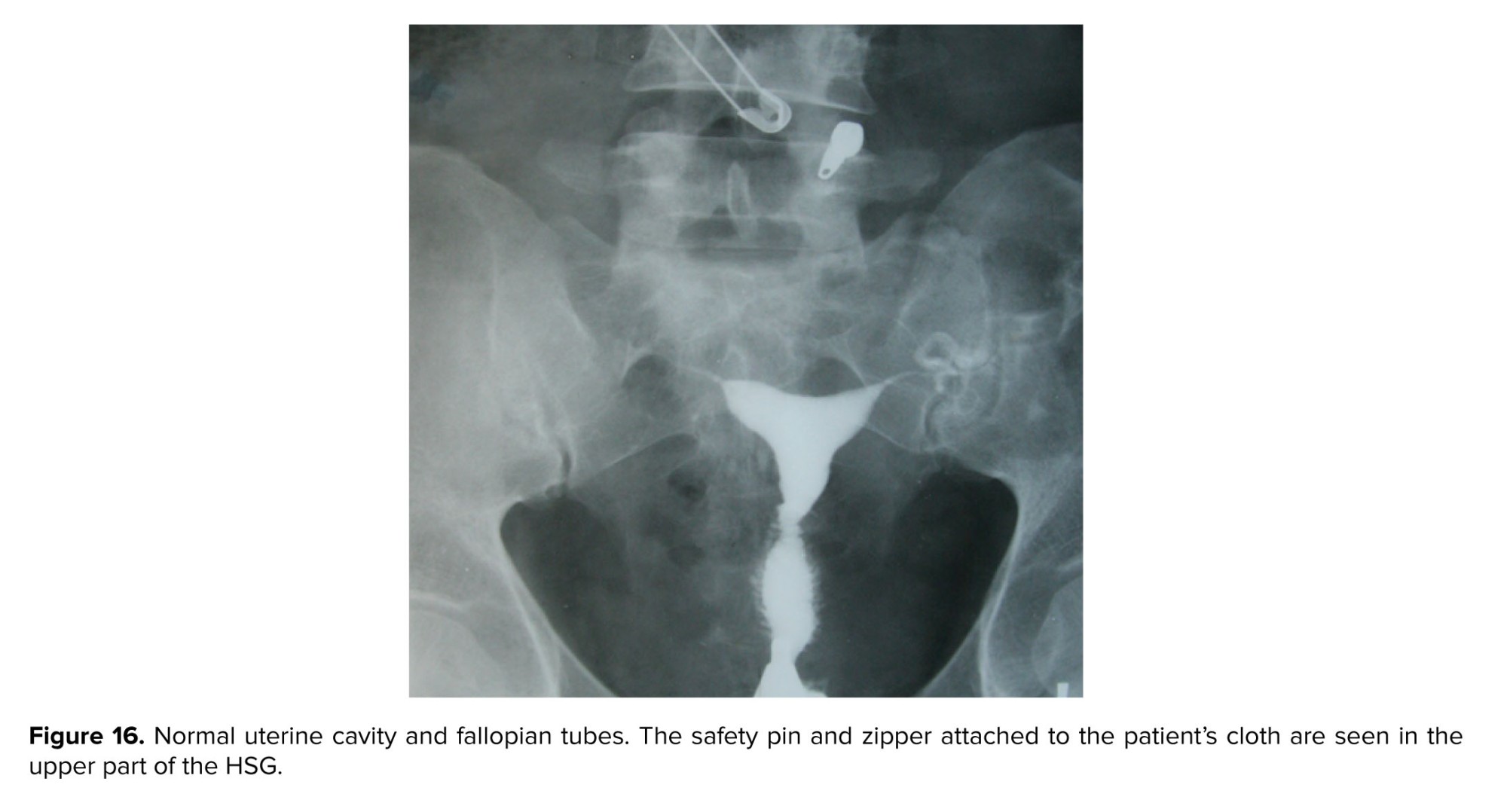

- External foreign bodies

-

External bodies and objects related to patient clothes appearing as dense structures in HSG may interfere with the diagnosis of pelvic anomalies. Opaque objects in clothes or on the skin may appear to be within the pelvis (Figure 16). In case of ambiguity, patients should be covered with a sheet after taking off all their clothes.

- Conclusion

Compared to other imaging and surgical procedures, HSG constitutes a reliable and cost-effective procedure for evaluating genital diseases. In addition to opaque areas showing the uterus and fallopian tubes patency, other soft tissues, pelvic bones, and their anomalies are visible in HSG.

Being familiar with the pathologies of pelvic tissues and accurately interpreting HSG images are therefore essential in identifying and treating gynecological diseases.

Data availability

Data supporting our findings can be sent by the co-author, upon request.

Author contributions

Firoozeh Ahmadi, Fattaneh Pahlavan, and Fereshteh Hosseini: participated in study design and data collection. Fattaneh Pahlavan and Fereshteh Hosseini wrote the manuscript. Firoozeh Ahmadi supervised the writing of manuscript. Fereshteh Hosseini collected and embedded images in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

In commemoration of the late Dr. Gholam Shahrzad, who donated an amazing and valuable collection of HSG images to us.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Being familiar with the pathologies of pelvic tissues and accurately interpreting HSG images are therefore essential in identifying and treating gynecological diseases.

Data availability

Data supporting our findings can be sent by the co-author, upon request.

Author contributions

Firoozeh Ahmadi, Fattaneh Pahlavan, and Fereshteh Hosseini: participated in study design and data collection. Fattaneh Pahlavan and Fereshteh Hosseini wrote the manuscript. Firoozeh Ahmadi supervised the writing of manuscript. Fereshteh Hosseini collected and embedded images in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

In commemoration of the late Dr. Gholam Shahrzad, who donated an amazing and valuable collection of HSG images to us.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Fertility & Infertility

References

1. Luczynska E, Zbigniew K. Diagnostic imaging in gynecology. Ginekol Pol 2022; 93: 63-69. [DOI:10.5603/GP.a2021.0209] [PMID]

2. Baușic A, Coroleucă C, Coroleucă C, Comandașu D, Matasariu R, Manu A, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound vs. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) value in endometriosis diagnosis. Diagnostics 2022; 12: 1767. [DOI:10.3390/diagnostics12071767] [PMID] [PMCID]

3. Gündüz R, Ağaçayak E, Okutucu G, Karuserci ÖK, Peker N, Çetinçakmak MG, et al. Hysterosalpingography: A potential alternative to laparoscopy in the evaluation of tubal obstruction in infertile patients? Afr Health Sci 2021; 21: 373-378. [DOI:10.4314/ahs.v21i1.47] [PMID] [PMCID]

4. Panda SR, Kalpana BJC. The diagnostic value of hysterosalpingography and hysterolaparoscopy for evaluating uterine cavity and tubal patency in infertile patients. Cureus 2021; 13: e12526. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.12526]

5. Martí-Bonmatí L. Hysterosalpingography and fertility: A technical relationship. Fertil Steril 2018; 110: 642. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.034] [PMID]

6. Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Olpin JD, Kennedy AM, Gaballah AH, Foster BR, et al. Nongynecologic findings seen at pelvic US. Radiographics 2017; 37: 2045-2062. [DOI:10.1148/rg.2017170083] [PMID]

7. Zulfiqar M, Shetty A, Tsai R, Gagnon M-H, Balfe DM, Mellnick VM. Diagnostic approach to benign and malignant calcifications in the abdomen and pelvis. Radiographics 2020; 40: 731-753. [DOI:10.1148/rg.2020190152] [PMID]

8. Heursen EM, González Partida MD, Paz Expósito J, Navarro Díaz F. Osteomesopyknosis-a benign axial hyperostosis that can mimic metastatic disease. Skeletal Radiol 2016; 45: 141-146. [DOI:10.1007/s00256-015-2216-3] [PMID]

9. Ahmadi F, Hosseini F, Javam M, Pahlavan F. Hysterosalpingography findings of leiomyomas and how they look in artistic eyes: New diagnostic signs. Br J Radiol 2021; 94: 20200019. [DOI:10.1259/bjr.20200019] [PMID] [PMCID]

10. Taborda F, Fernandes B, Lobão MJ. Calcified uterine myoma: An infrequent radiologic finding. Lusiadas Sci J 2021; 2: 82-83.

11. Zhu M, Li J, Duan J, Yang J, Gu W, Jiang W. Bilateral ovarian fibromas as the sole manifestation of Gorlin syndrome in a 22-year-old woman: A case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol 2023; 18: 118. [DOI:10.1186/s13000-023-01406-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Ahmadi F, Zafarani F, Shahrzad G. Hysterosalpingographic appearances of female genital tract tuberculosis: Part I. fallopian tube. Int J Fertil Steril 2014; 7: 245-252.

13. Siddiqui E. Calcifications. In: Eltorai AEM, Hyman C-H, Healey TT. Essential radiology review. USA: Springer; 2019. 277-278. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-26044-6_80] [PMCID]

14. Ladumor H, Al-Mohannadi S, Ameerudeen FS, Ladumor S, Fadl S. TB or not TB: A comprehensive review of imaging manifestations of abdominal tuberculosis and its mimics. Clin Imaging 2021; 76: 130-143. [DOI:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.02.012] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |