Sat, Feb 21, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 11 (November 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(11): 937-952 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR-UU-AEC-32108

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Javanmard S, Najdegerami E, Razi M, Nikoo M. An experimental study on shrimp bioactive peptides restoring testicular function in a rat model of fatty liver disease via autophagy, redox balance, and energy transporters. IJRM 2025; 23 (11) :937-952

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3544-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3544-en.html

1- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran. ,e.gerami@urmia.ac.ir

3- Department of Basic Science, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

4- Artemia and Aquaculture Research Institute, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran. ,

3- Department of Basic Science, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

4- Artemia and Aquaculture Research Institute, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran.

Keywords: NAFLD, Bioactive peptides, Oxidative stress, Autophagy, Spermatogenesis, Gene expression, Rat.

Full-Text [PDF 6781 kb]

(259 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (170 Views)

Full-Text: (15 Views)

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by excessive hepatic lipid accumulation and may progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, or cancer (1). Oxidative stress (OS) is central to NAFLD pathogenesis (2) and causes Sertoli and germ cell dysfunction (3). NAFLD-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase lipid peroxidation and disrupt spermatogenesis (4). Approximately 40% of infertile men are affected by NAFLD (5). Since no specific treatment exists and chemical drugs often cause adverse effects, alternative strategies are being investigated, including natural antioxidants such as bioactive peptides, which have shown potential to mitigate OS and improve liver health.

Bioactive peptides are extracted from different protein sources using proteolytic enzymes and typically consist of 2-22 amino acids in their structure. Their antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory properties (6), and manipulation of cellular signaling pathways (7) are some of the proposed underlying processes. These peptides lessen OS, inflammation, and maintain cellular integrity, perhaps defending the function of the testicles under stressful situations (8). However, the precise effects might vary depending on the HPs composition and source, indicating the need for more study to completely understand these pathways.

Seminiferous tubules, the functional units of spermatogenesis, are composed of germ cells and Sertoli cells (SCs) (9). SCs regulate germ-cell development through structural, metabolic, and immunological functions (10) and their interactions with germ cells are highly vulnerable to inflammatory, oxidative, and hormonal disturbances (9). Glucose uptake by SCs occurs via GLUT-1 and GLUT-3, after which glucose is converted to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase; this lactate serves as the primary energy source for germ cells and is exported through MCT-4 and taken up by MCT-1 in spermatogonial cells (11). Despite expressing GLUTs and glycolytic enzymes, germ cells depend on SCs for nutrient supply (12). SC metabolism (including lactate synthesis and MCT-4 expression) is further shaped by growth factors, cytokines, and steroid hormones (13, 14). Evidence indicates that NAFLD disrupts GLUT1, GLUT3, and MCT4 activity in rat Sertoli and germ cells, thereby altering testicular glucose transport and energy homeostasis (15, 16).

OS also modulates the expression of autophagy-related genes in the testes. Autophagy, a central degradative pathway, is activated in response to oxidative injury and contributes to testicular homeostasis. Key autophagy regulators, including microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and Beclin-1, are upregulated in SCs to support germ-cell survival and differentiation under stress conditions (17).

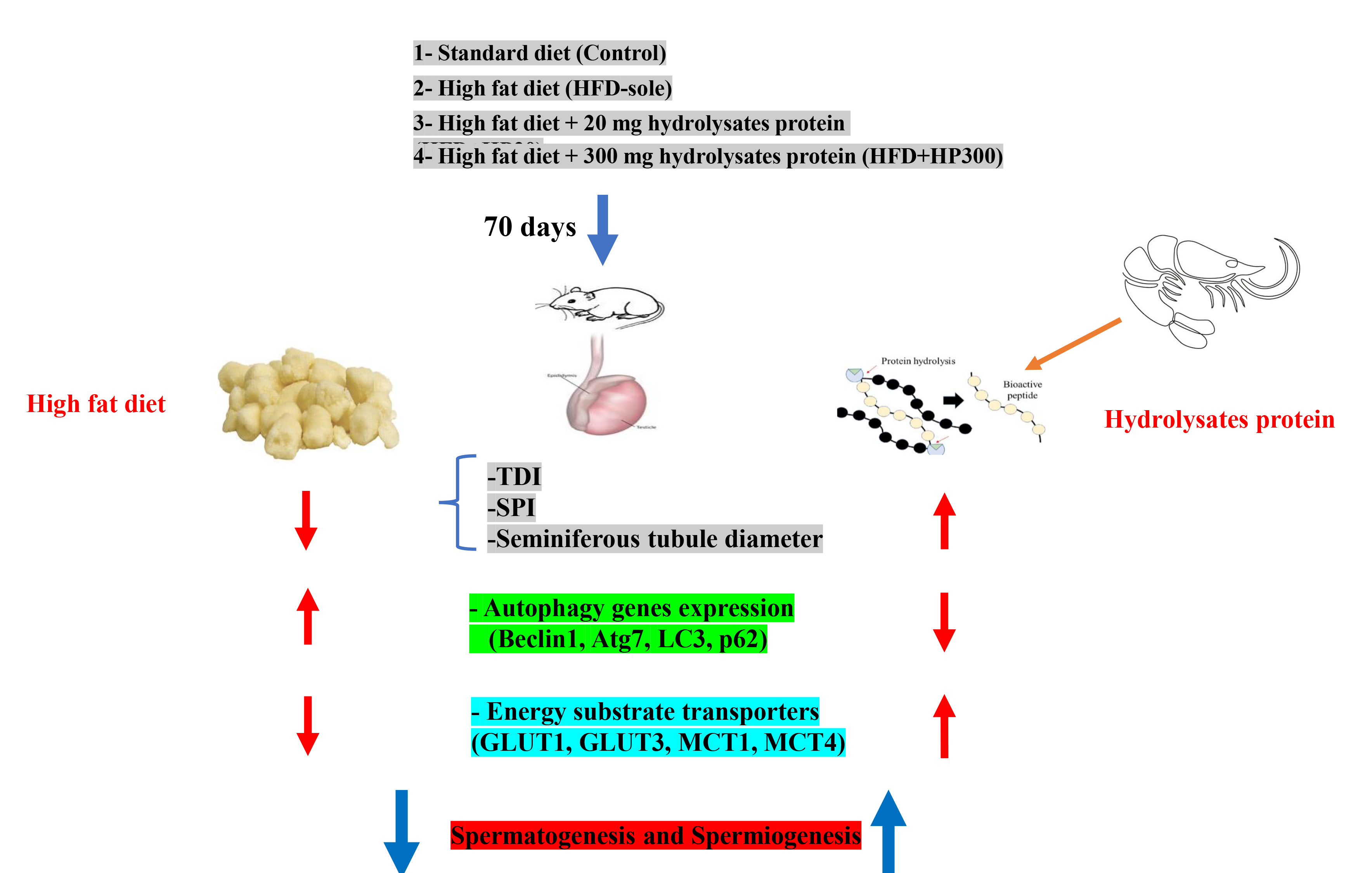

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the protective effects of whiteleg shrimp bioactive peptides against NAFLD-induced testicular dysfunction. Unlike prior work focused mainly on hepatic parameters, the present investigation examines testicular redox balance, autophagy-related gene expression, and the distribution of major energy-transport proteins (GLUT1, GLUT3, MCT1, and MCT4) in Sertoli and germ cells. By combining biochemical measurements with morphometric and histological analyses, such as seminiferous tubule diameter, SCs counts, tubular differentiation index (TDI), and spermiogenesis index (SPI), this study provides new insights into how shrimp peptides help preserve spermatogenesis and testicular structure under metabolic stress. Accordingly, we aimed to determine the effects of HPs on OS, autophagy-related gene expression, and key energy transporters (GLUT-3, GLUT-1, and MCT-4) in NAFLD-associated testicular dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioactive peptides preparation

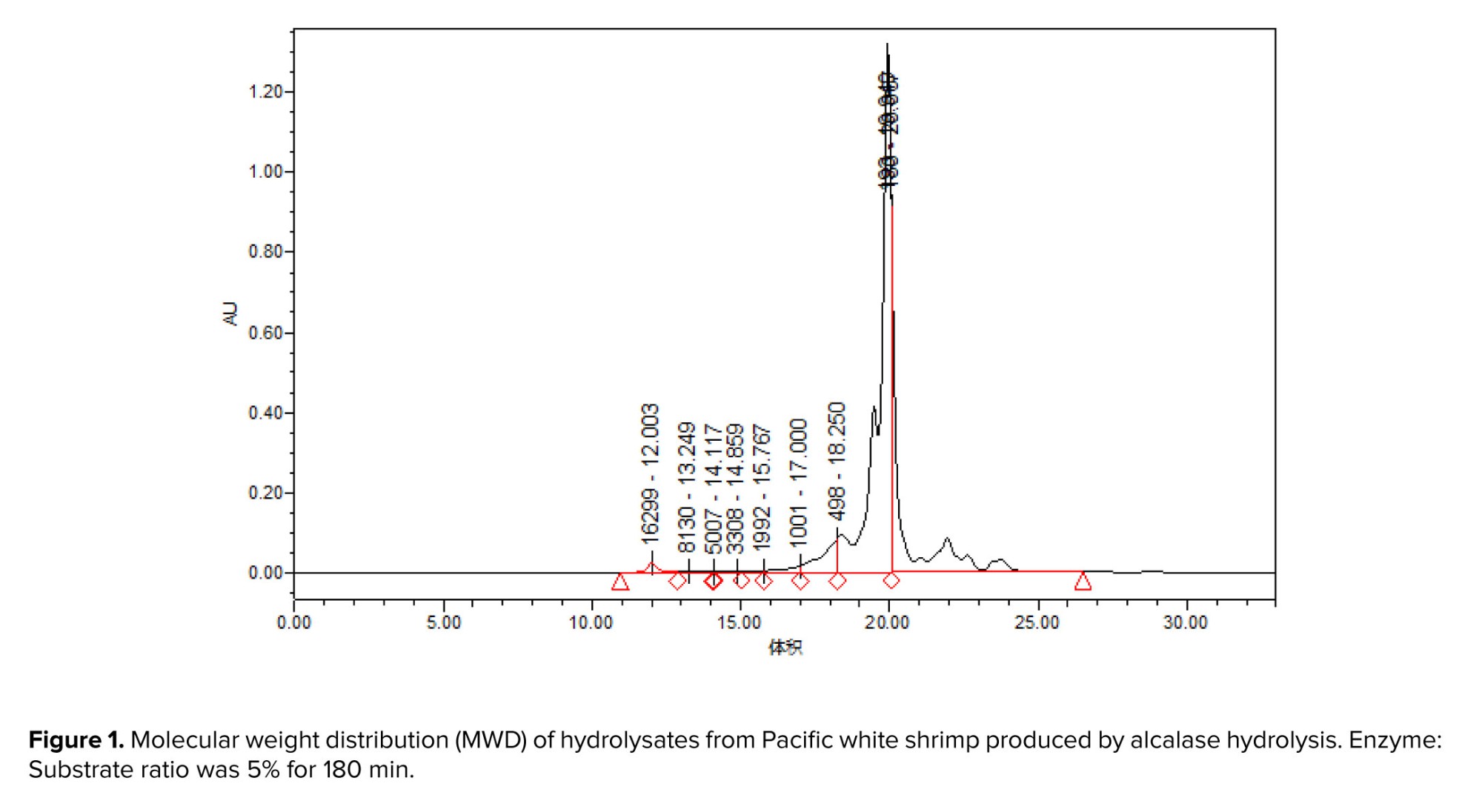

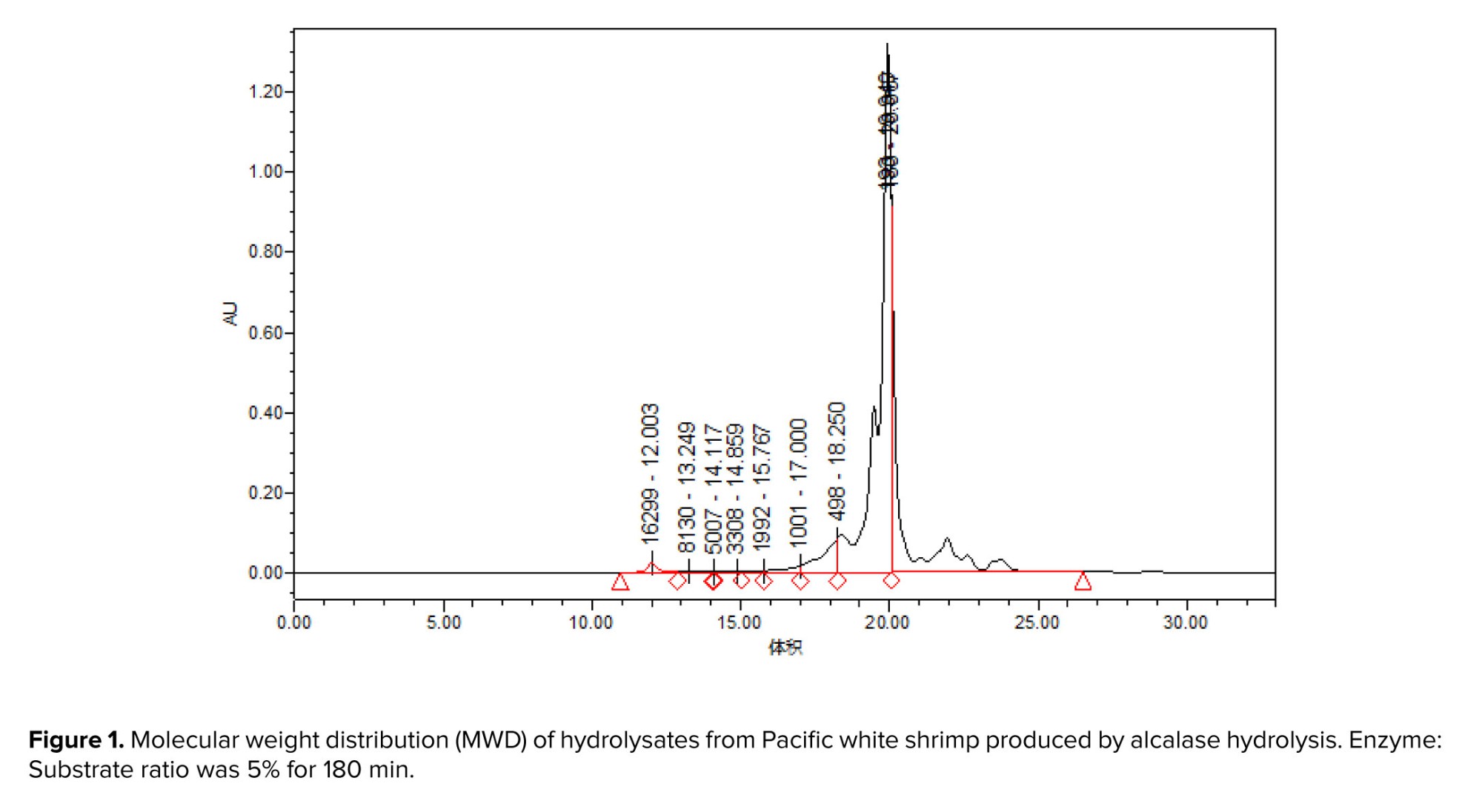

Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) processing by-products were obtained from Daryahodeh Co. (Bushehr, Iran) and subsequently delivered to the Artemia and Aquaculture Research Institute at Urmia University, Urmia, Iran for further analysis. The by-products were subsequently comminuted using a 3 mm grinder (Pars Khazar Co., Tehran, Iran) and homogenized with distilled water in a 1:1 weight-to-volume ratio for 2 min using a Heidolph DIAX900 homogenizer (Heidolph Instruments GmbH, Schwabach, Germany). Alcalase enzyme hydrolysis of the homogenized mixture was conducted at 40°C for 3 hr, maintaining an initial pH of 7.1. The homogenate was continuously stirred throughout the hydrolysis. Following hydrolysis, the reaction was terminated by incubation in a boiling water bath (95°C) for 10 min. The mixture was then filtered through cheesecloth, followed by centrifugation (4000 g, 20 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was subsequently lyophilized. Analysis of the resulting bioactive peptides revealed a distribution of peptide chain lengths following hydrolysis. Notably, approximately 40% of the total peptides exhibited a molecular weight below 500 Da (18) (Figure 1).

2.2. Experiment design, animals, and diets

In this experimental study, 24 male Wistar rats, weighing an average of 230.2 ± 23 gr (8 wk) at the start of the experiment, were obtained from the Department of Biology (Urmia University, Urmia, Iran). The rats were housed in groups of 6 under controlled conditions (25°C, 12-hr light/dark cycle) and acclimated to a standard chow diet for a week. The rats were randomly allocated to one of 4 experimental groups once they had acclimated: control (standard chow diet), HFD-sole (high-fat diet), HFD+HP20 (high-fat diet supplemented with 20 mg/kg BW bioactive peptides), and HFD+HP300 (high-fat diet supplemented with 300 mg/kg BW bioactive peptides) (19) and fed for 10 wk. The HFD was formulated by enriching a standard chow diet with 10% animal fat and 5% fructose.

Freshly prepared HPs were diluted daily in 4 ml of distilled water at designated concentrations (20 and 300 mg/kg BW) and administered orally to the rats in the HFD+HP groups using an oro-gastric feeding tube. The control group received a standard chow diet and 4 ml of distilled water via the same route.

2.3. Tissue preparation and histological analysis

To guarantee minimal stress during the procedure of blood sample and biopsy, the rats were humanely put to sleep using an overdose of sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (90 mg/kg). The tissues of the right testicles were removed, preserved in Bouin's solution, subjected to standard processing, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned using a rotary microtome (LKB, UK) at a thickness of 5 µm. Tissue slices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological examinations. Stained slides were examined under light microscopy (Leica, Germany) at various magnifications (200x, 400x, and 1000x) to assess seminiferous tubule morphology. For each animal (n = 5), 30 seminiferous tubules were evaluated across 5 tissue sections. Spermatogenesis efficiency was quantified using the SPI and the percentage of seminiferous tubules exhibiting a positive TDI. A positive TDI score signifies the presence of > 3 distinct germ cell layers within a seminiferous tubule. Evaluation adhered to established criteria for identifying spermatogenic stages within the tubules (20).

2.4. OS

To assess total antioxidant capacity (TAC), testicular tissue homogenates were subjected to a colorimetric assay. Protein content was determined using Lowry's method. TAC results were normalized to protein content. The ferric reducing antioxidant power assay was employed to evaluate the tissue's capacity to reduce ferric ions. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, an indicator of lipid peroxidation, were quantified using a thiobarbituric acid reactants assay (Arsam Fara Biot, Iran). Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels were determined using a 5,5'-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid based assay (Arsam Fara Biot, Iran), while oxidized glutathione (GSSG) was measured using a glutathione test kit (Navand Salamat, Iran). Absorbance measurements were taken at the specified wavelengths (412 nm).

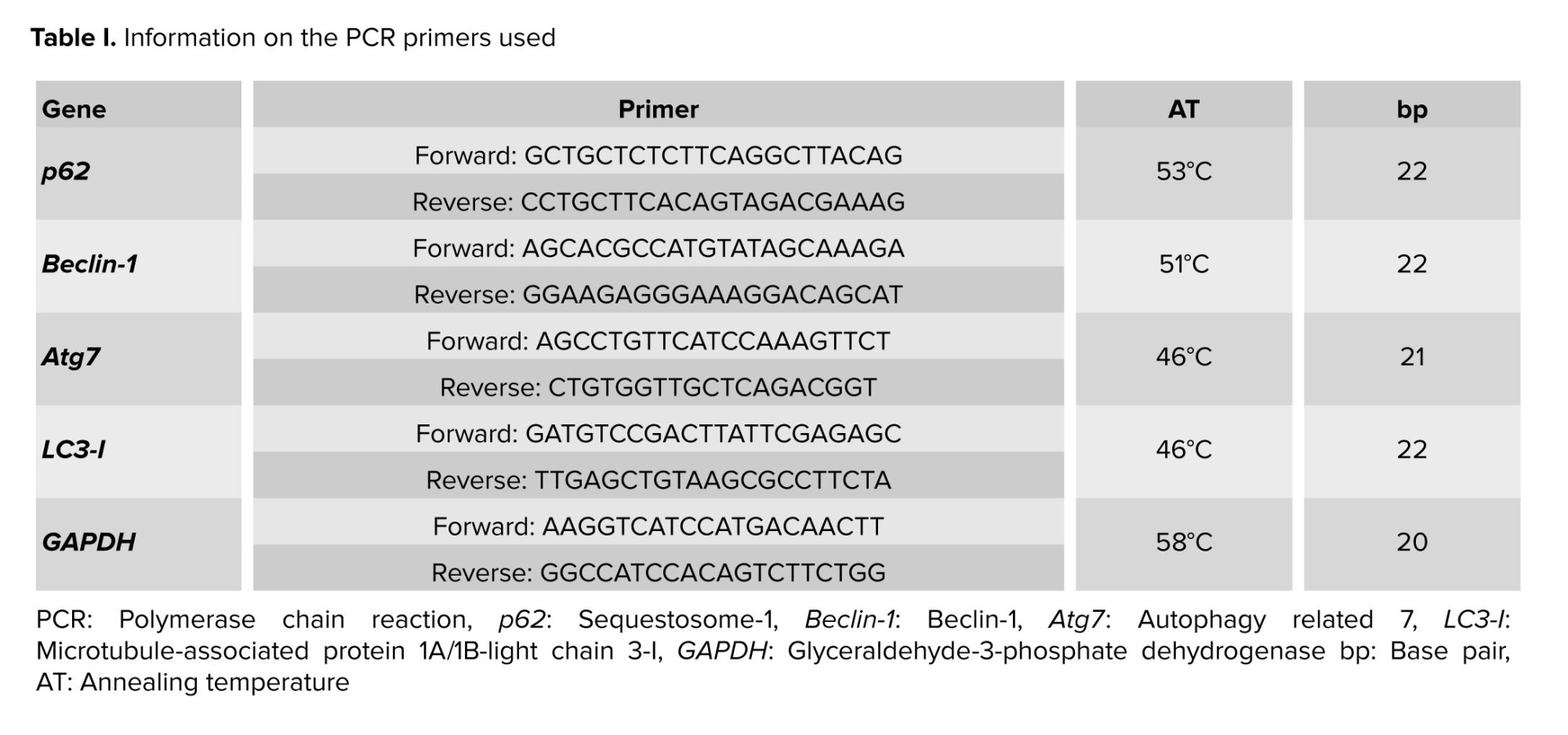

2.5. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and RNA isolation

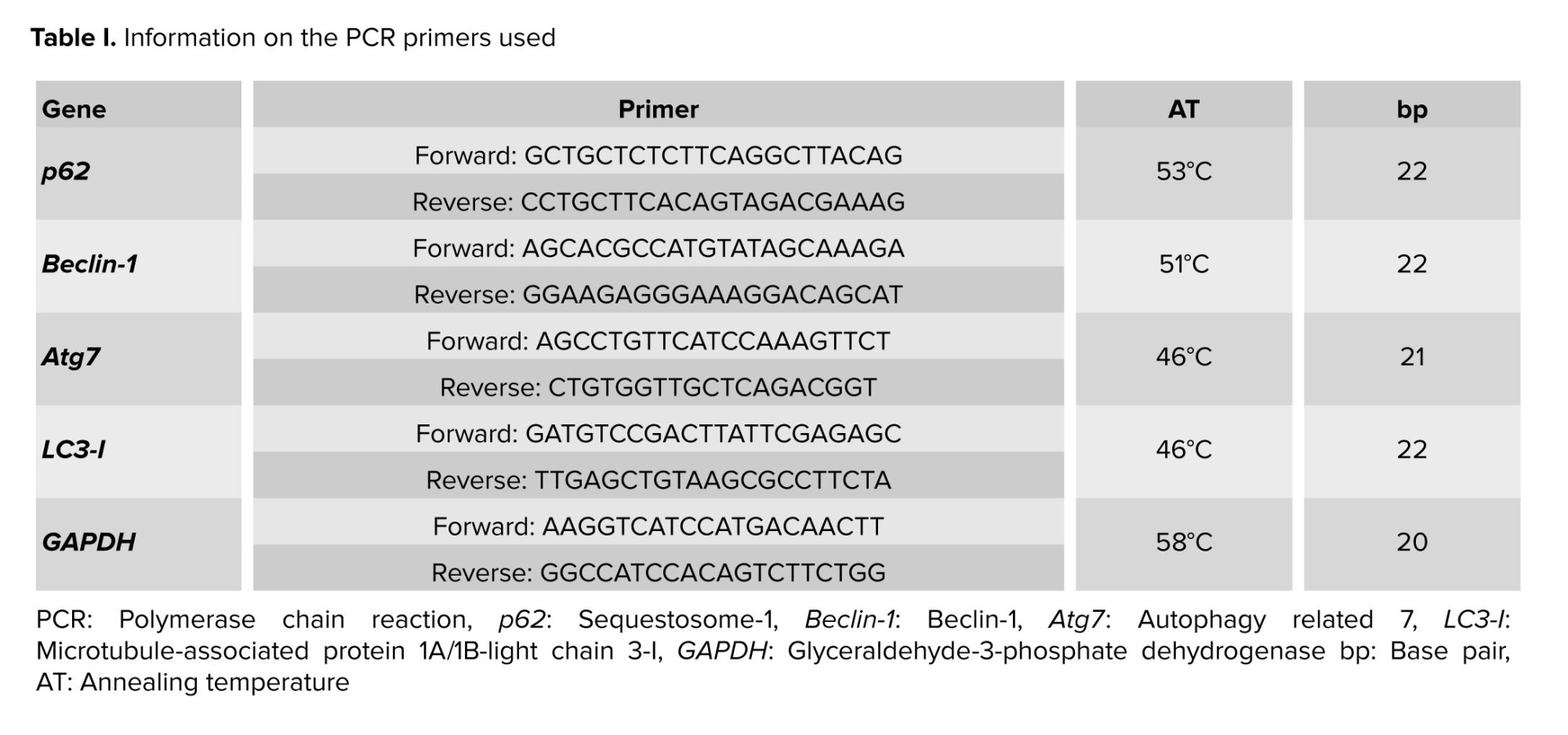

Total RNA was extracted from testicular tissue using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and assessed for quality and quantity using spectrophotometry. Only high-quality RNA samples were used for cDNA synthesis, which was performed using a commercially available reverse transcription kit. qRT-PCR was conducted on a MyGo PCR thermal cycler (Life Technologies) using SYBR green master mix (mention brand name and supplier) and gene-specific primers (Table I). GAPDH served as the internal control for calculating the relative gene expression levels using the 2^-ΔCt technique (21).

2.6. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Following preparation, heating, deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval, tissue slices were used for IHC procedures. The primary antibody (Elabsciences, USA) was added to the tissue sections and left in contact with them under controlled conditions (overnight at 4°C) so that the antibody could bind to its target antigens in the tissue. After that slides were treated for an hour at 37°C with a secondary antibody. Hematoxylin & Eosin was used to stain nuclei, and diamethybenzidine was used to stain proteins. Serving as a negative control was normal IgG. The presence of LC3-I/II+ protein was shown by brown stains. In the end, 20 seminiferous tubules were chosen per cross-section for the purpose of counting LC3-I/II+ cells, and these cells were then counted per one seminiferous tubule (ST, 3 sections/animal; in total: 18 sections/group). Also, for IHC staining of GLUT1 (spermatogonia, SCs), GLUT3 (spermatogonia, spermatocyte, SCs), MCT-1 (spermatogonia, spermatocyte, SCs), and MCT-4 (SCs) proteins, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies (Elabsciences, USA), anti-GLUT-3 antibody (Elabsciences, USA), and anti-MCT-4 antibody (Elabsciences, USA). The LC3-I/II protein expression analysis criteria were also utilized to assess the expression of the MCT-1, MCT-4, GLUT1, and GLUT3 proteins (15).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Urmia University, Urmia, Iran, for the care and handling of laboratory animals (Code: IR-UU-AEC-32108).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 20.0). The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were evaluated through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene's test, respectively. Group comparisons to identify statistically significant differences were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc multiple comparison tests, including Tukey’s honestly significant difference or Dunnett’s test, as deemed appropriate.

3. Results

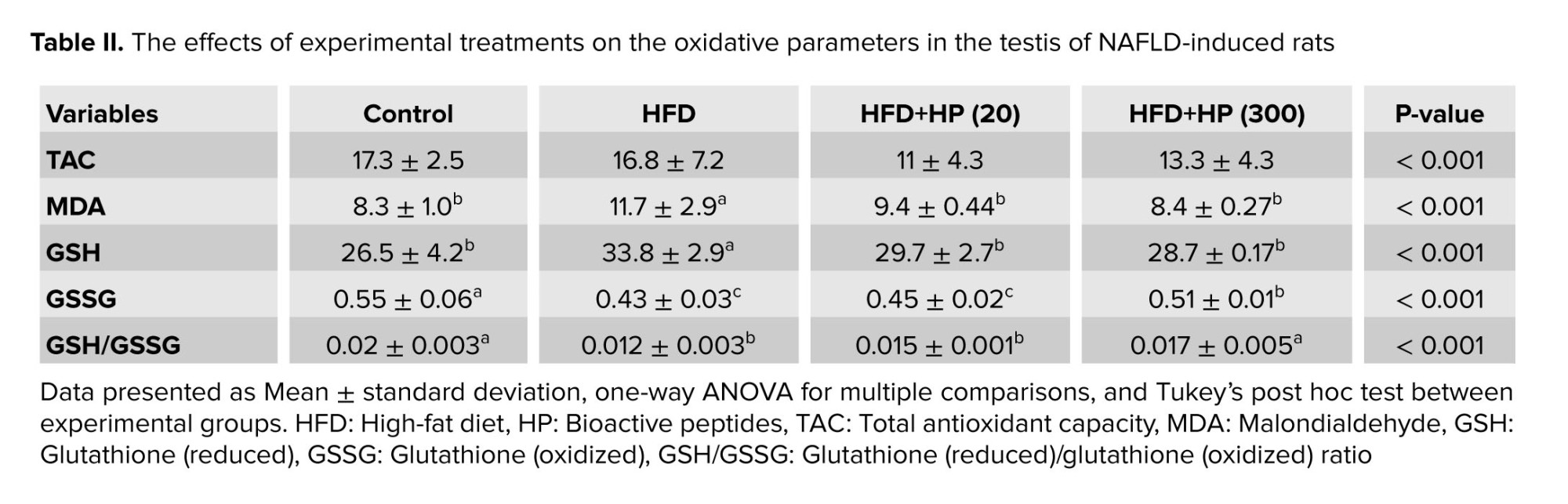

3.1. HPs and an imbalanced redox system in the testis

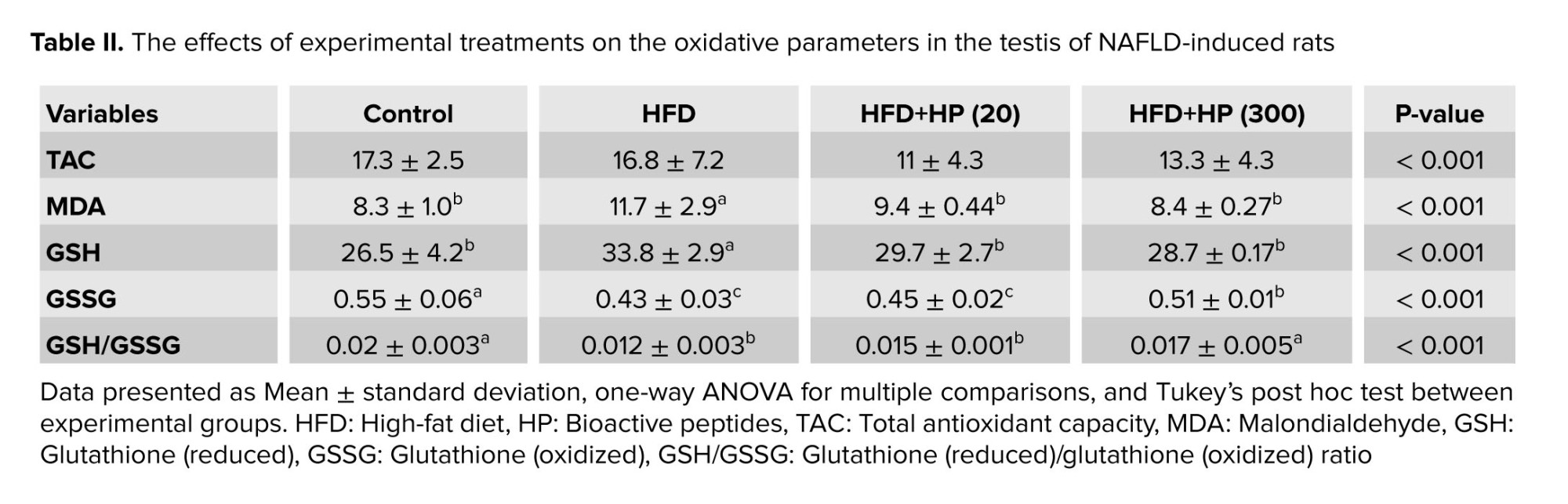

Table II presents the OS indices across experimental groups. Testicular TAC remained unchanged among treatments. The HFD-sole group showed a significant elevation in MDA levels compared with the control (p < 0.001), whereas both HP-treated groups (HFD+HP20 and HFD+HP300) exhibited significantly lower MDA content (p < 0.001). MDA values in peptide-receiving rats did not differ from the control. In the HFD-sole group, GSH levels increased and GSSG levels decreased compared to control, leading to a reduced GSH/GSSG ratio. HP supplementation normalized GSH, GSSG, and the GSH/GSSG ratio, with the most pronounced recovery observed in the HFD+HP300 group.

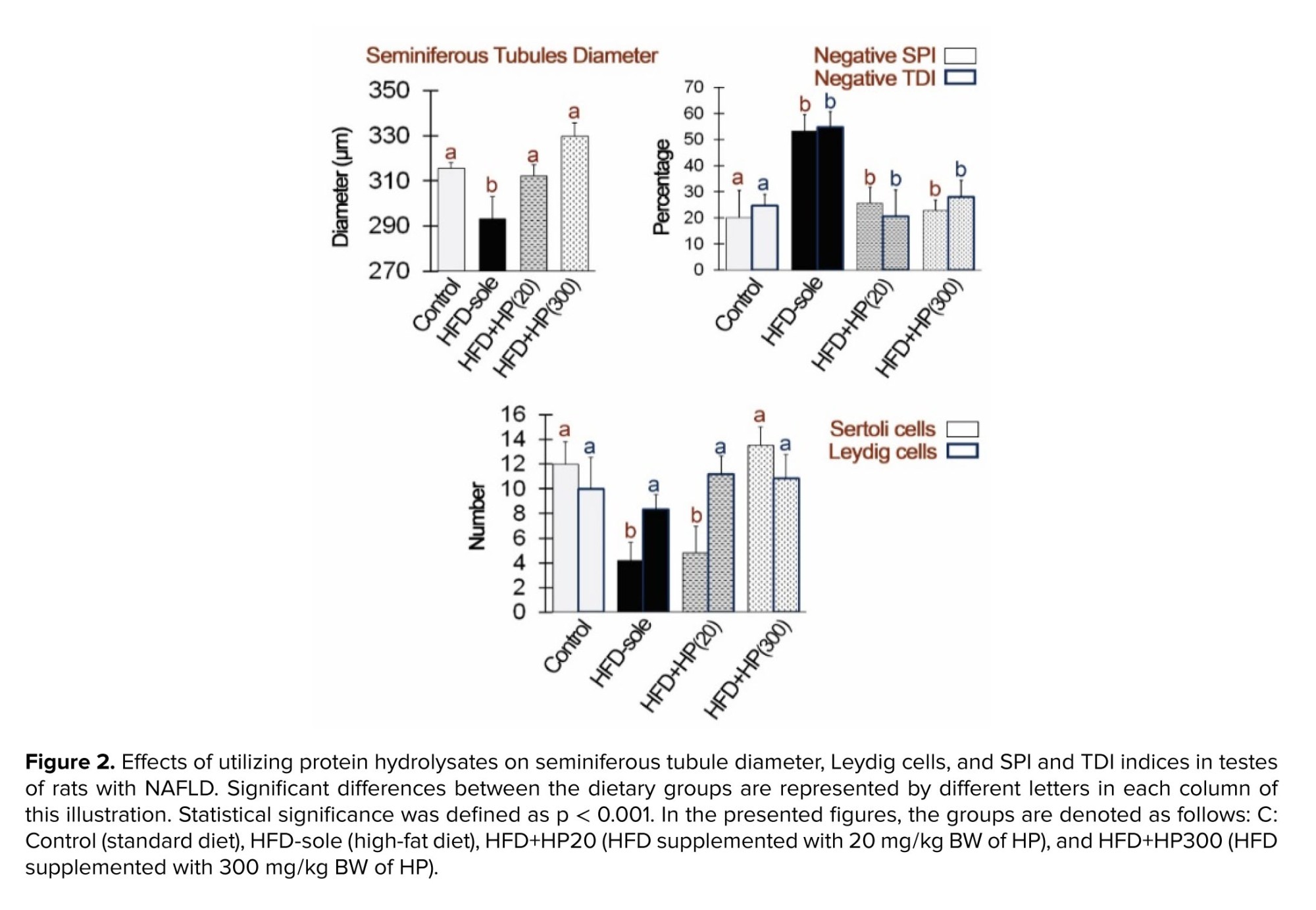

3.2. Effects of HP on germ cell differentiation and spermatogenesis ratios

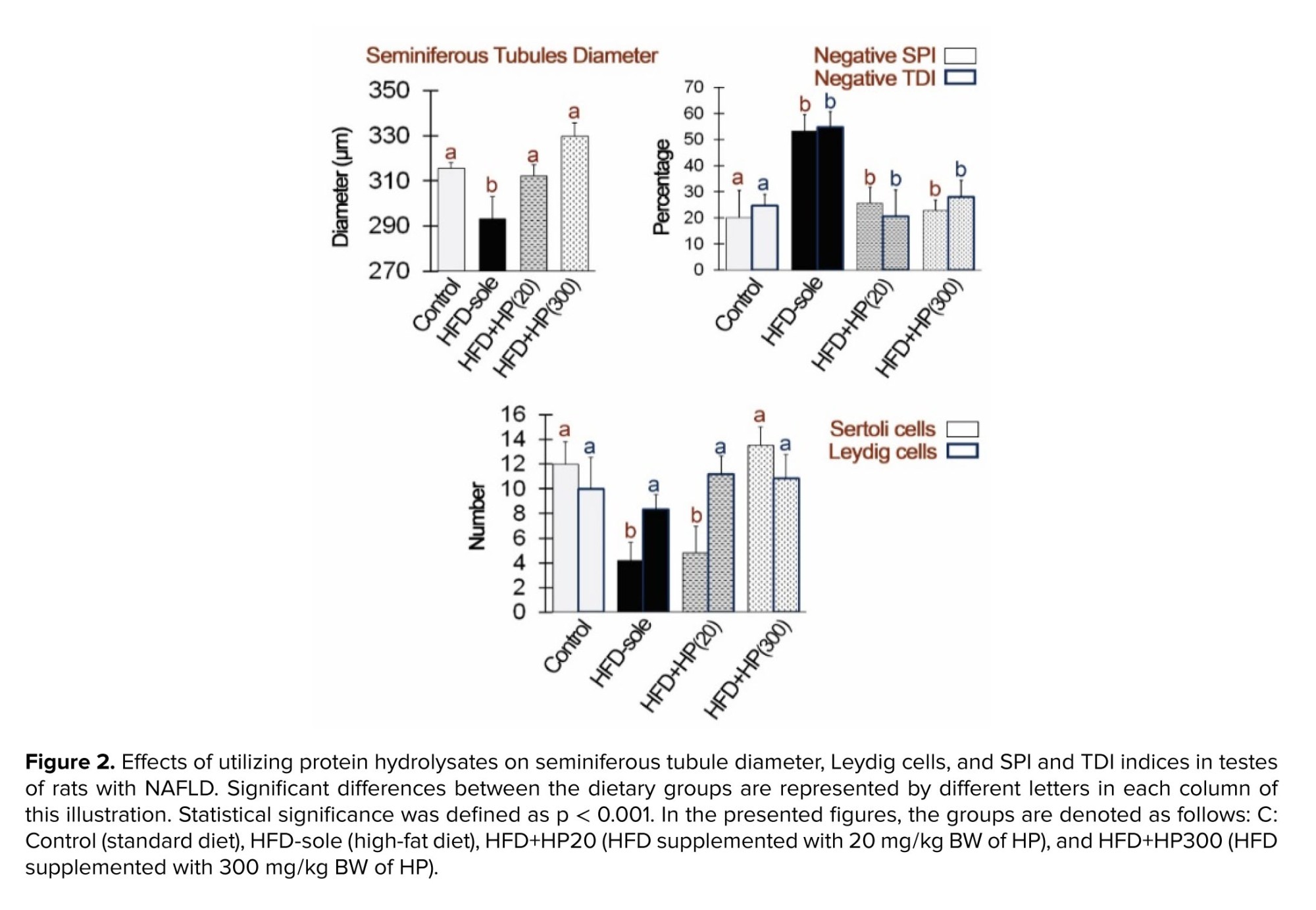

Figure 2 shows the influence of HP on Leydig and SC counts, as well as seminiferous tubule morphology. The HFD-sole group exhibited the smallest seminiferous tubule diameter and lowest SCs count, significantly differing from the control group (p < 0.01). Conversely, HP supplementation significantly increased seminiferous tubule diameter and SC numbers compared to the HFD-sole group (p < 0.01). While the number of Leydig cells remained comparable across all groups, the HFD-sole group demonstrated the highest levels of negative SPI and TDI, significantly differing from the control group (p < 0.01). HP administration significantly reduced these indices compared to the HFD-sole group (p < 0.01).

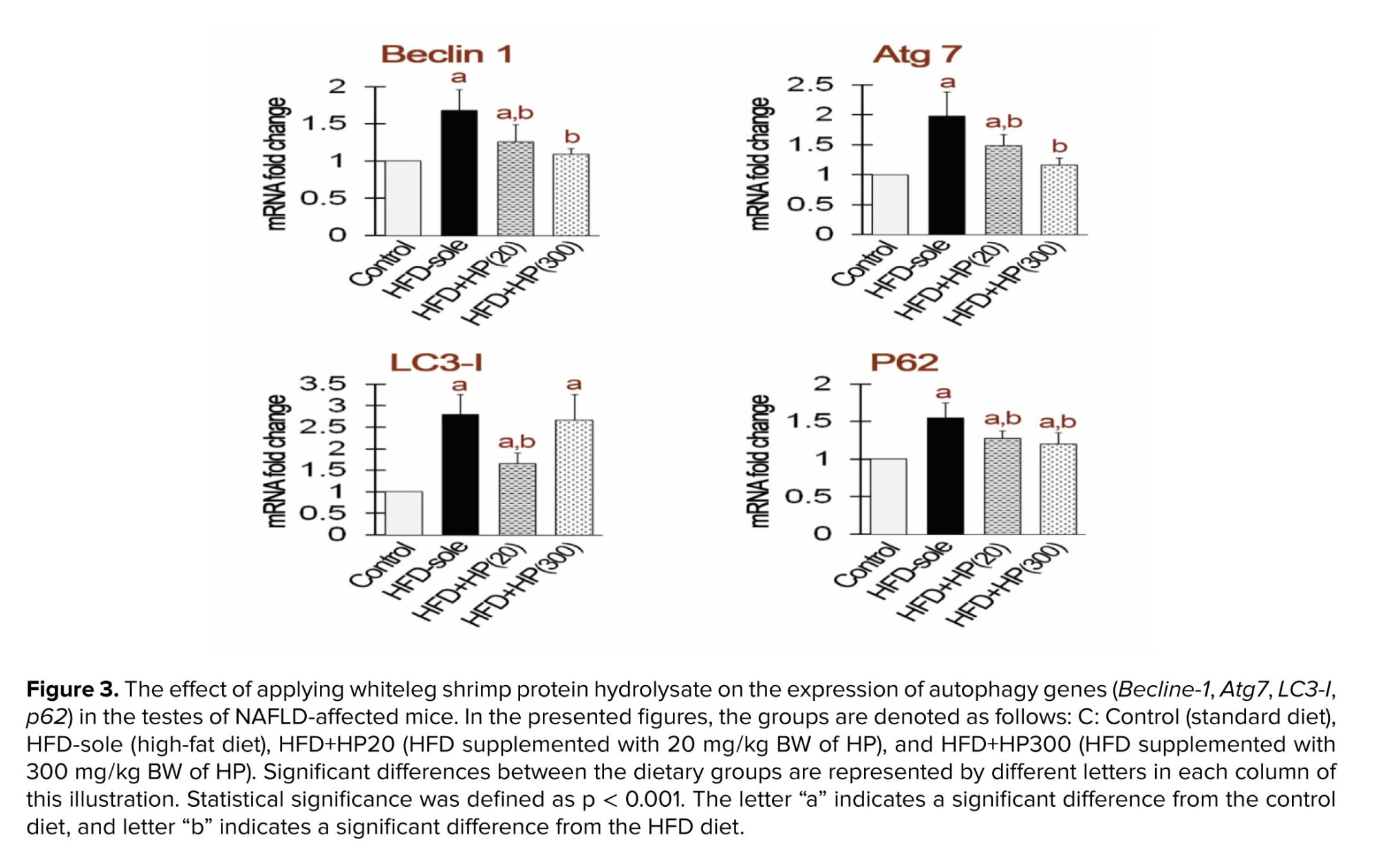

3.3. Impact of HP on autophagy gene expression in the testes

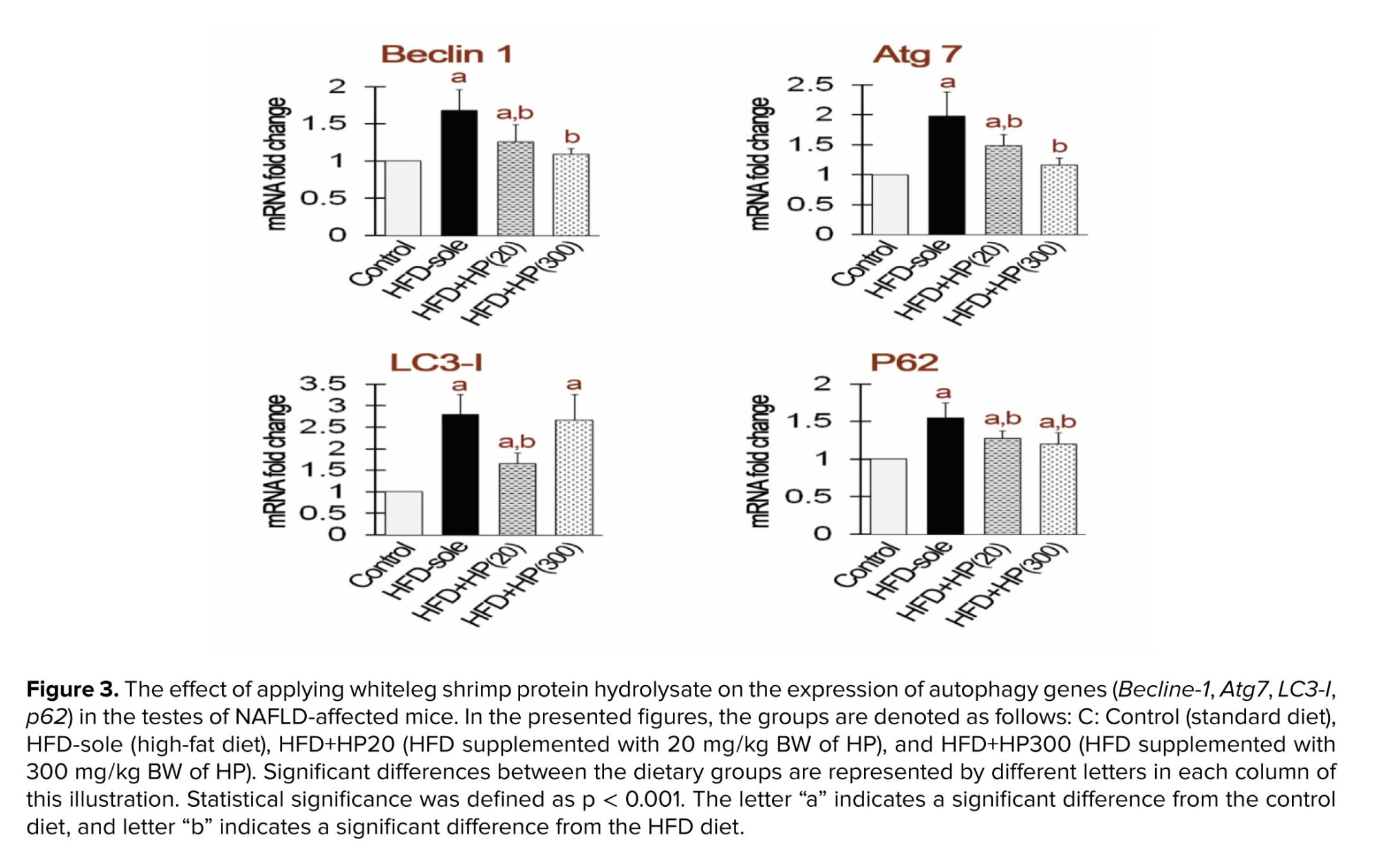

Figure 3 shows autophagy-related gene expression in testicular tissue. Both the HFD and HFD+HP20 groups showed significantly higher Beclin-1 and Atg7 expression than the control (p < 0.05), whereas HFD+HP300 significantly reduced their expression relative to the HFD group (p < 0.05). All treatments increased LC3 expression compared with the control (p < 0.05); however, LC3 levels in HFD+HP20 were significantly lower than in the HFD group (p < 0.05). No significant difference was detected between HFD+HP300 and HFD (p > 0.05). p62 expression decreased in all groups compared with control (p < 0.05). Although HP treatments lowered p62 relative to HFD, its levels remained above control values (p < 0.05).

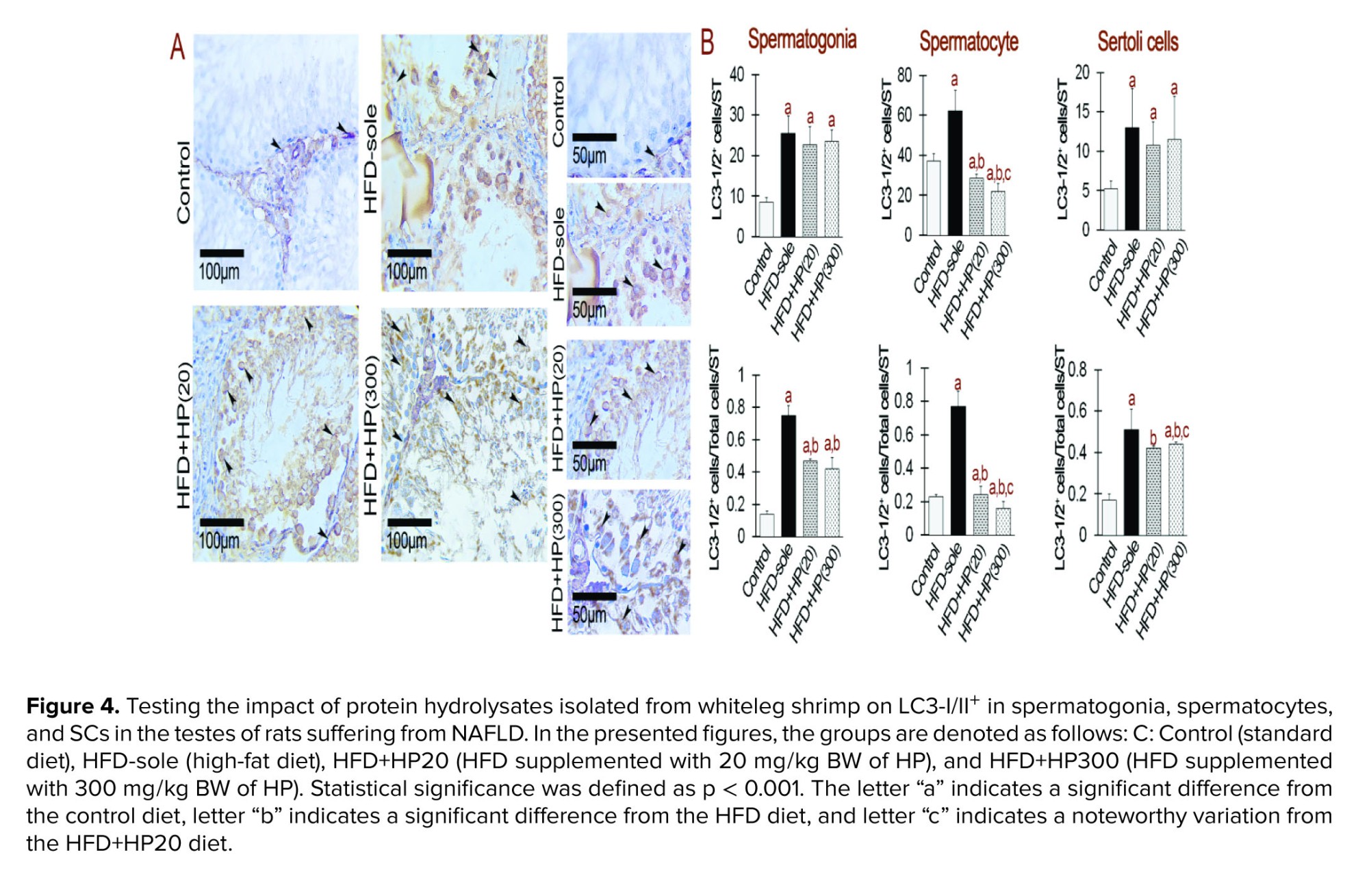

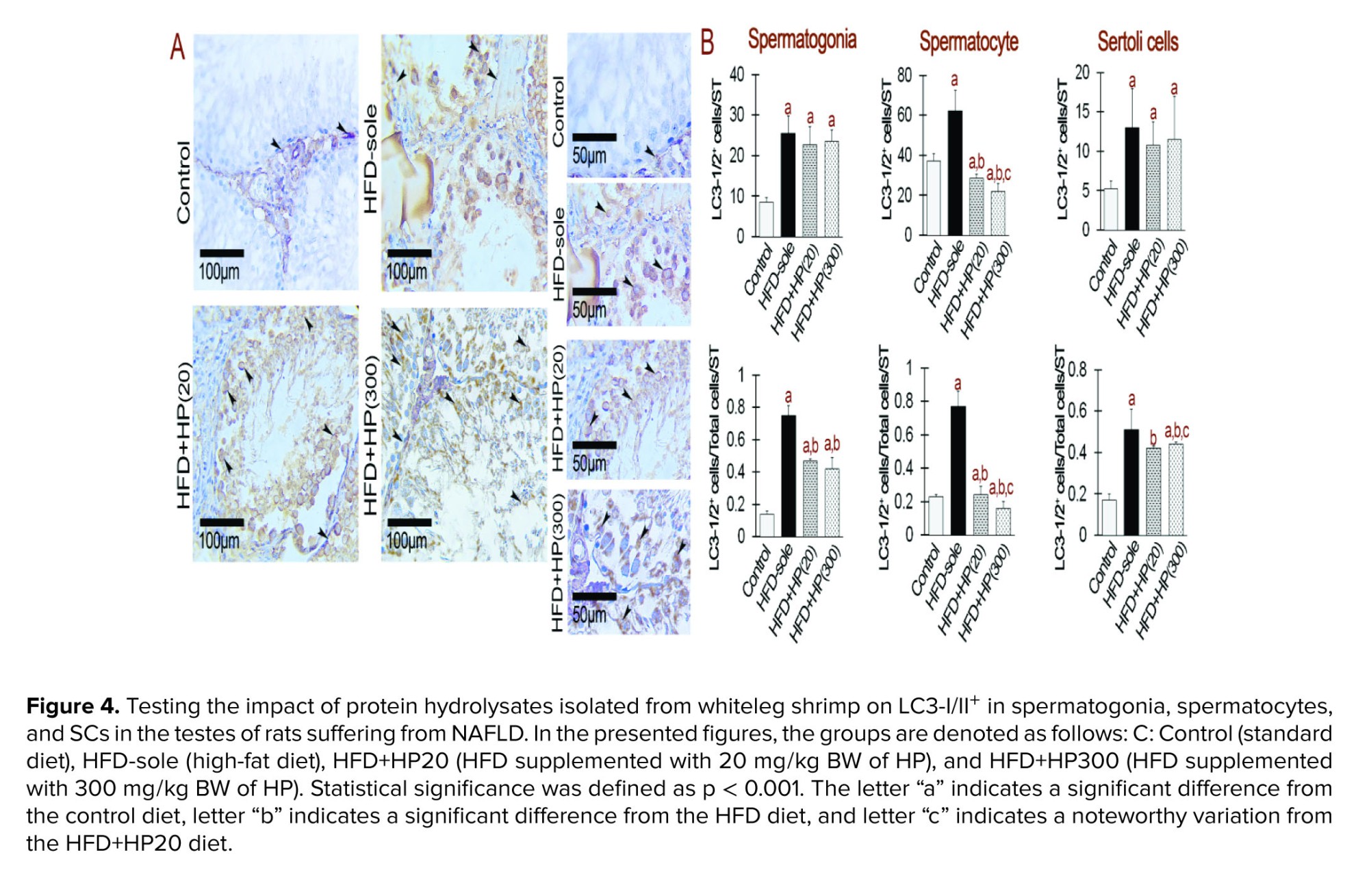

3.4. LC3-I/II staining indicates autophagy activity in experimental treatments

To evaluate the effects of different diets on autophagy, we used immunohistochemistry to stain LC3-I/II+, which is a major indicator of autophagy completion (Figure 4). The results showed that rats given HFD had higher expression of LC3-I/II+/total cells/ST, which differed statistically significantly from the control group (p < 0.001). Moreover, in comparison to the HFD group, the administration of HP significantly reduced the expression of LC3-I/II+ (p < 0.001). It is remarkable, nonetheless, that the expression level continued to be much greater than that of the control group (p < 0.001), suggesting that HP had a major effect. Interestingly, no statistically significant difference was observed between the 2 treatment groups' bioactive peptides concentrations (p > 0.001).

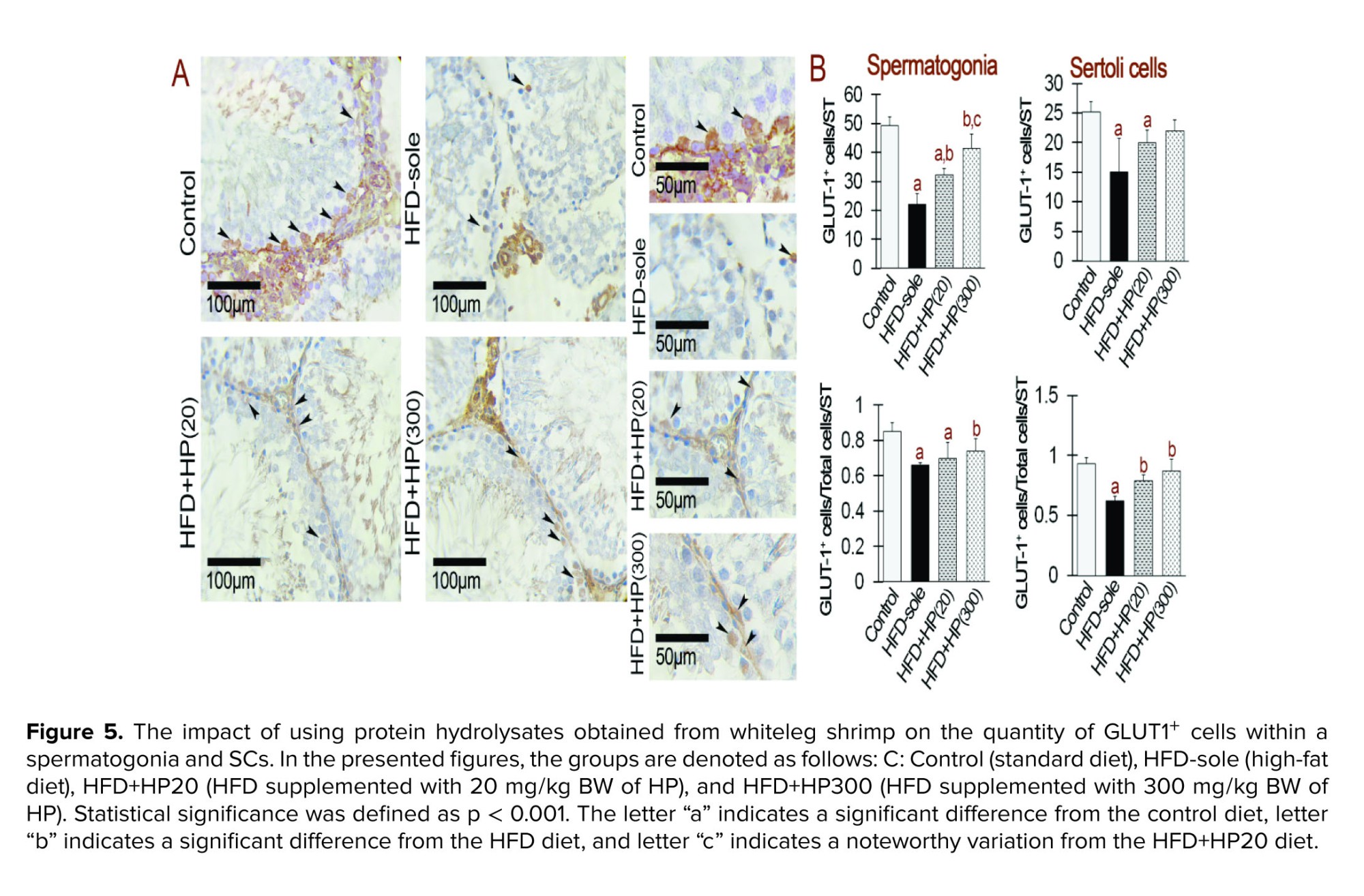

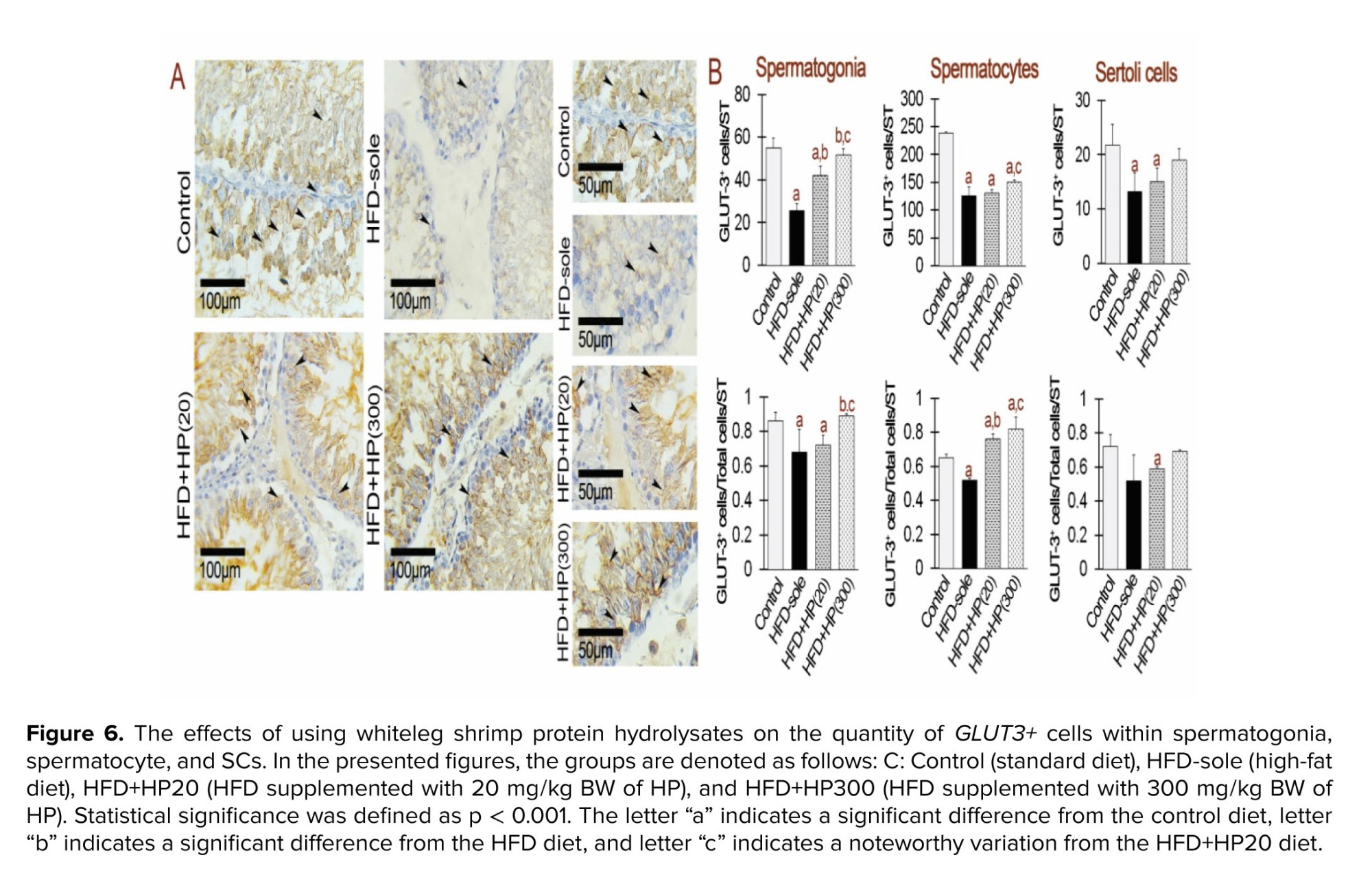

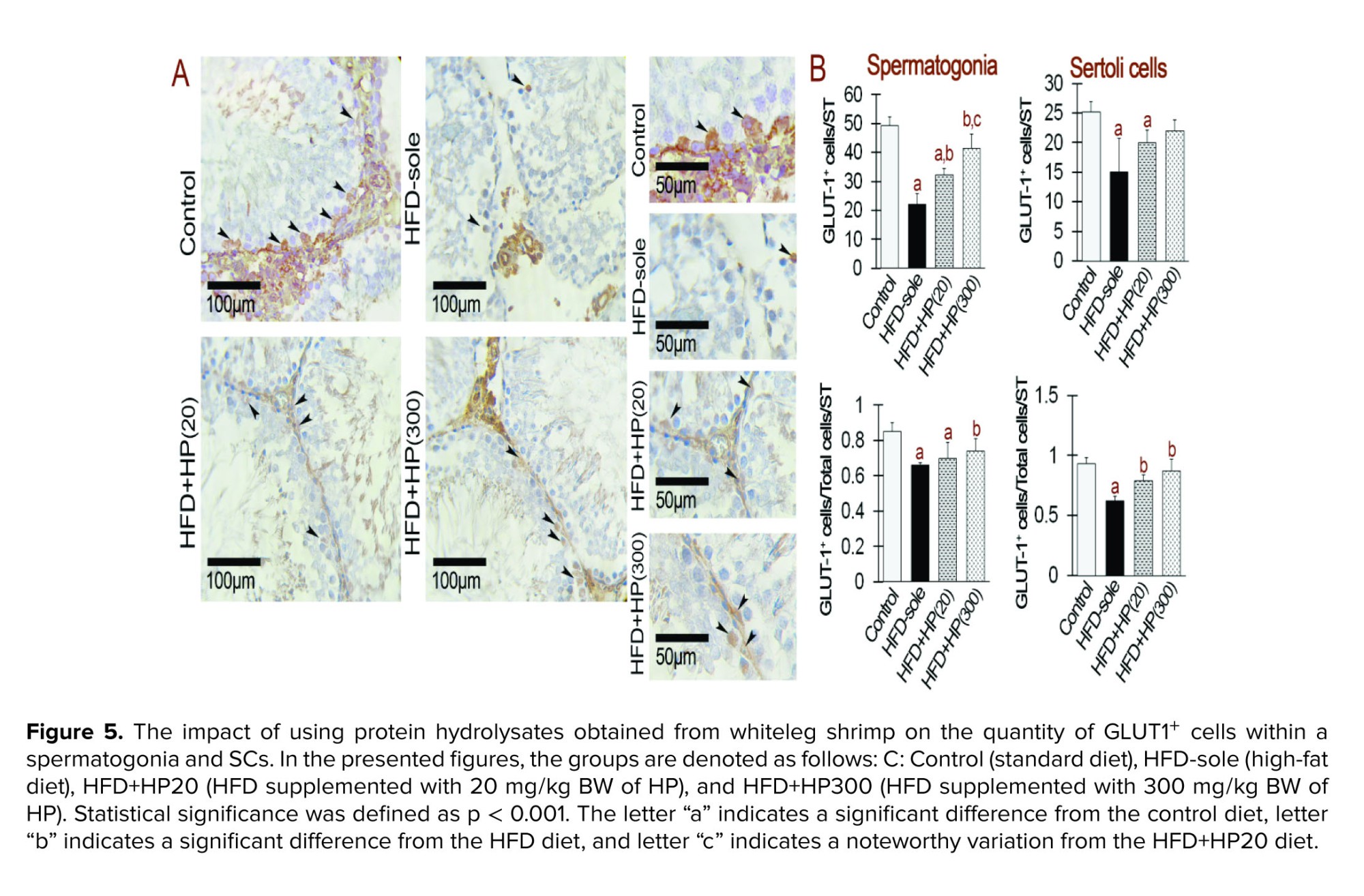

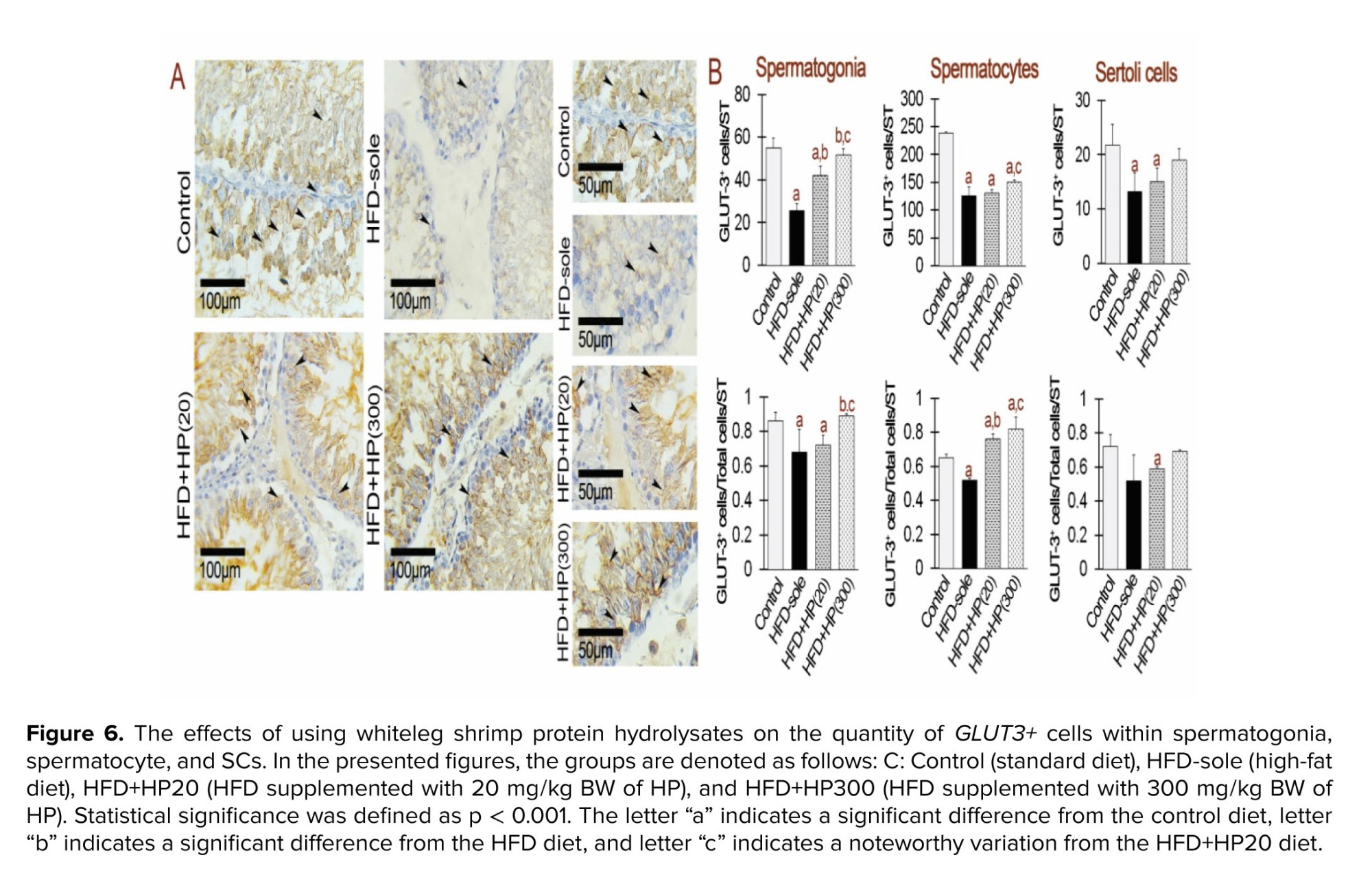

3.5. Upregulated signals with GLUT1 and GLUT3 staining using HP

IHC analysis showed marked changes in GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression in spermatogonia (Figures 5 and 6). Both the HFD and HFD+HP20 groups exhibited significantly reduced GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression compared with the control (p < 0.001), whereas HFD+HP300 significantly increased their expression relative to HFD (p < 0.001) and restored levels comparable to control. In SCs, GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression was similarly decreased in the HFD group (p < 0.001), while both HP doses significantly enhanced expression compared with HFD (p < 0.001), reaching values indistinguishable from the control group.

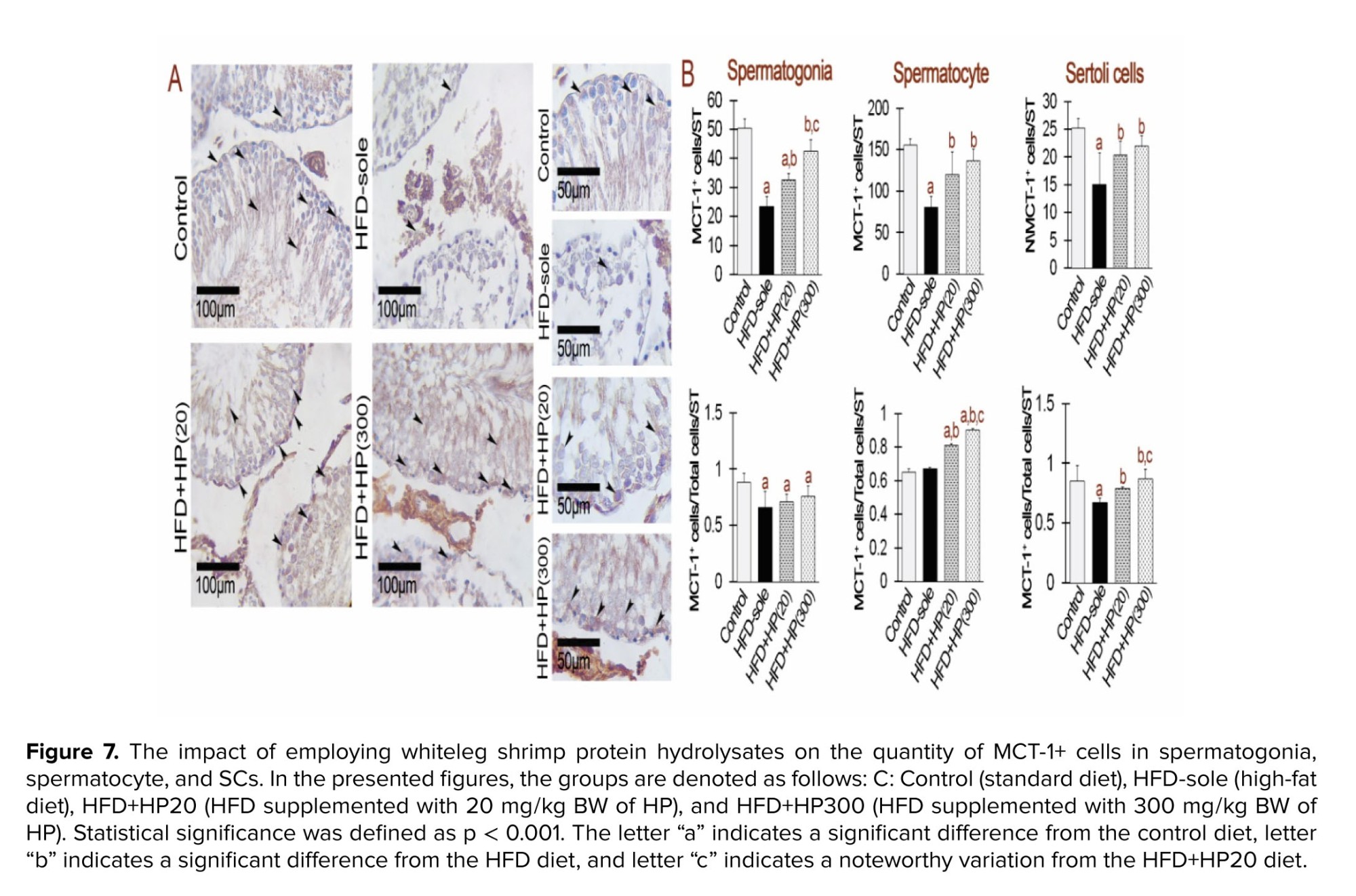

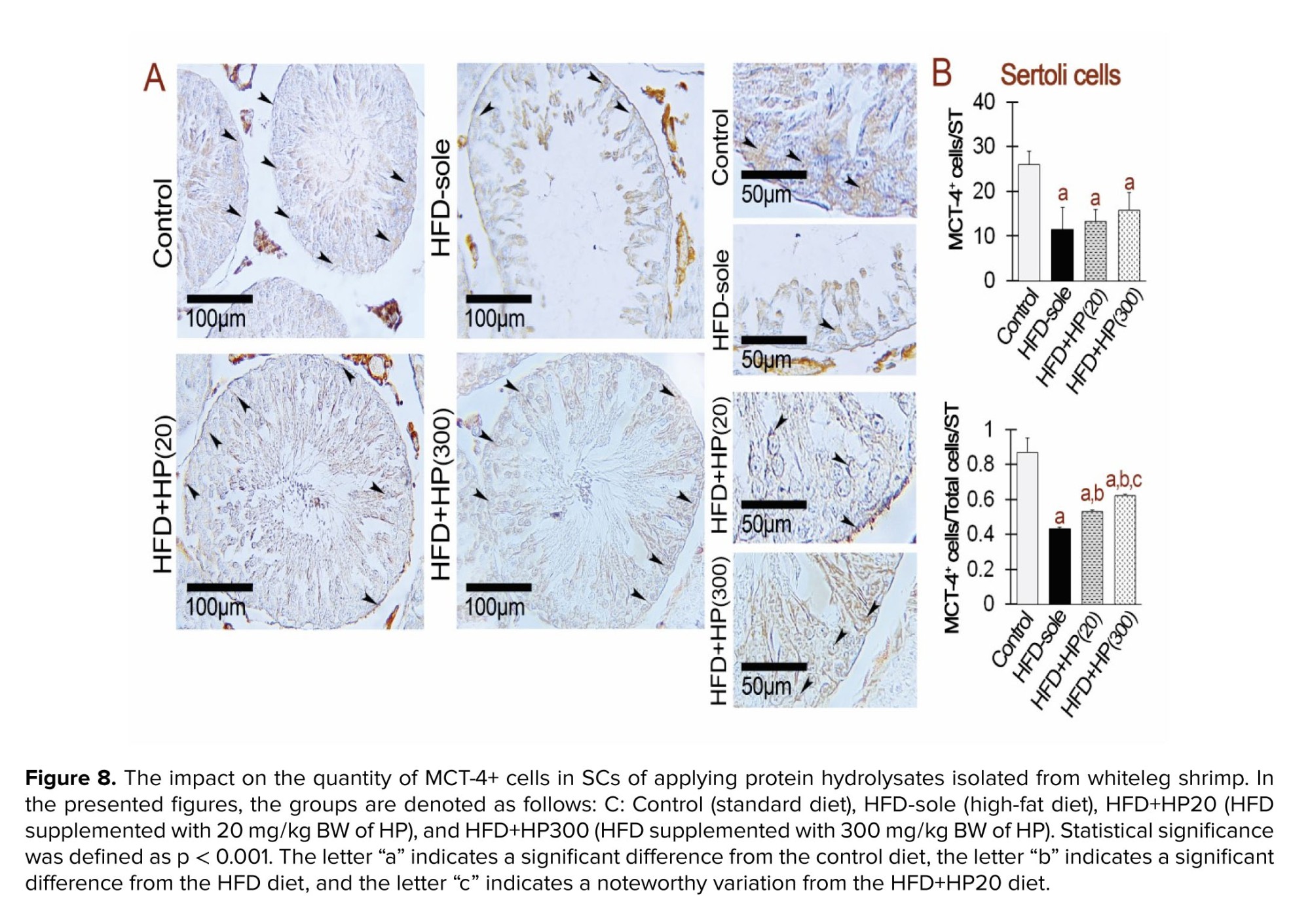

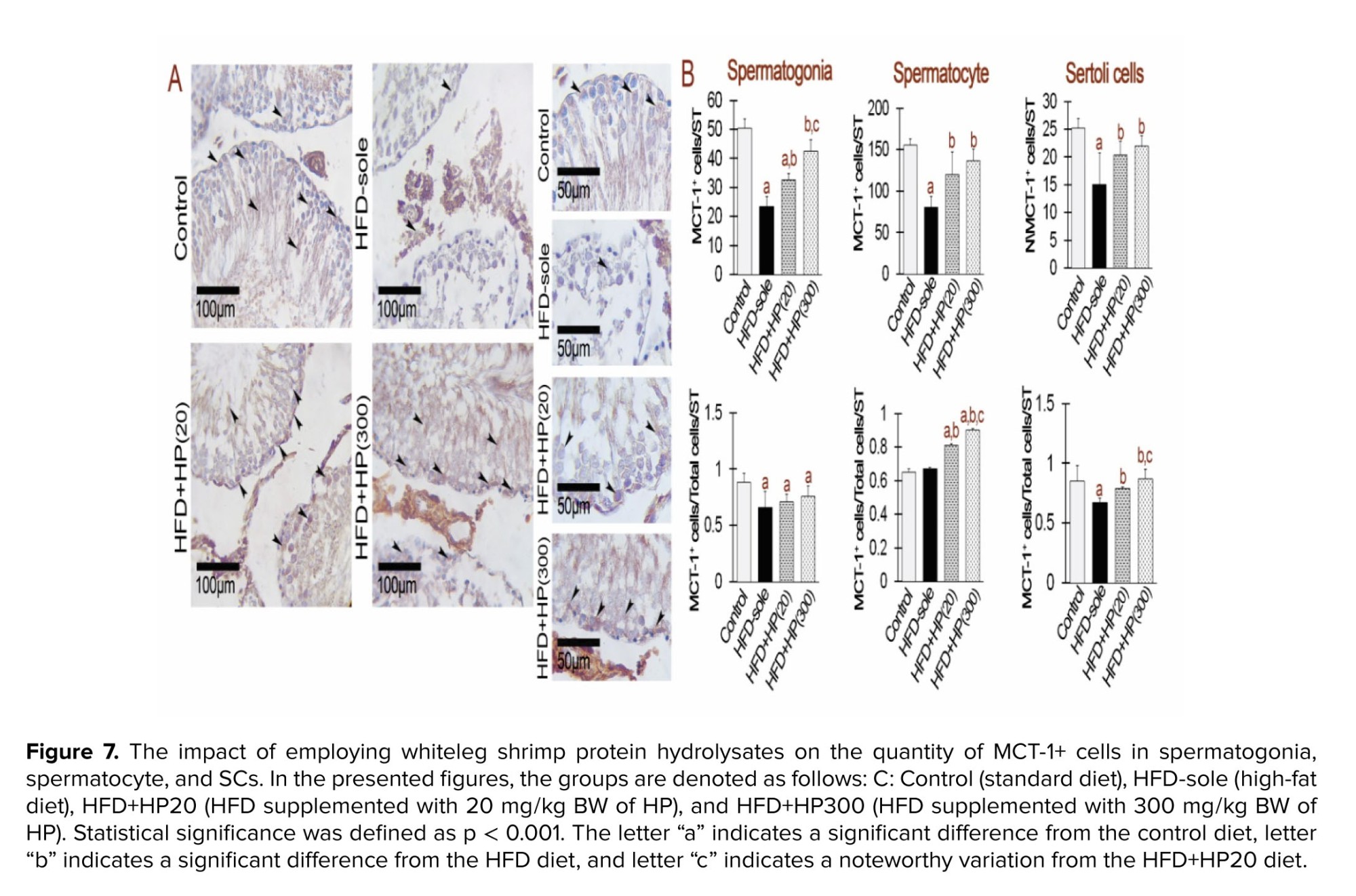

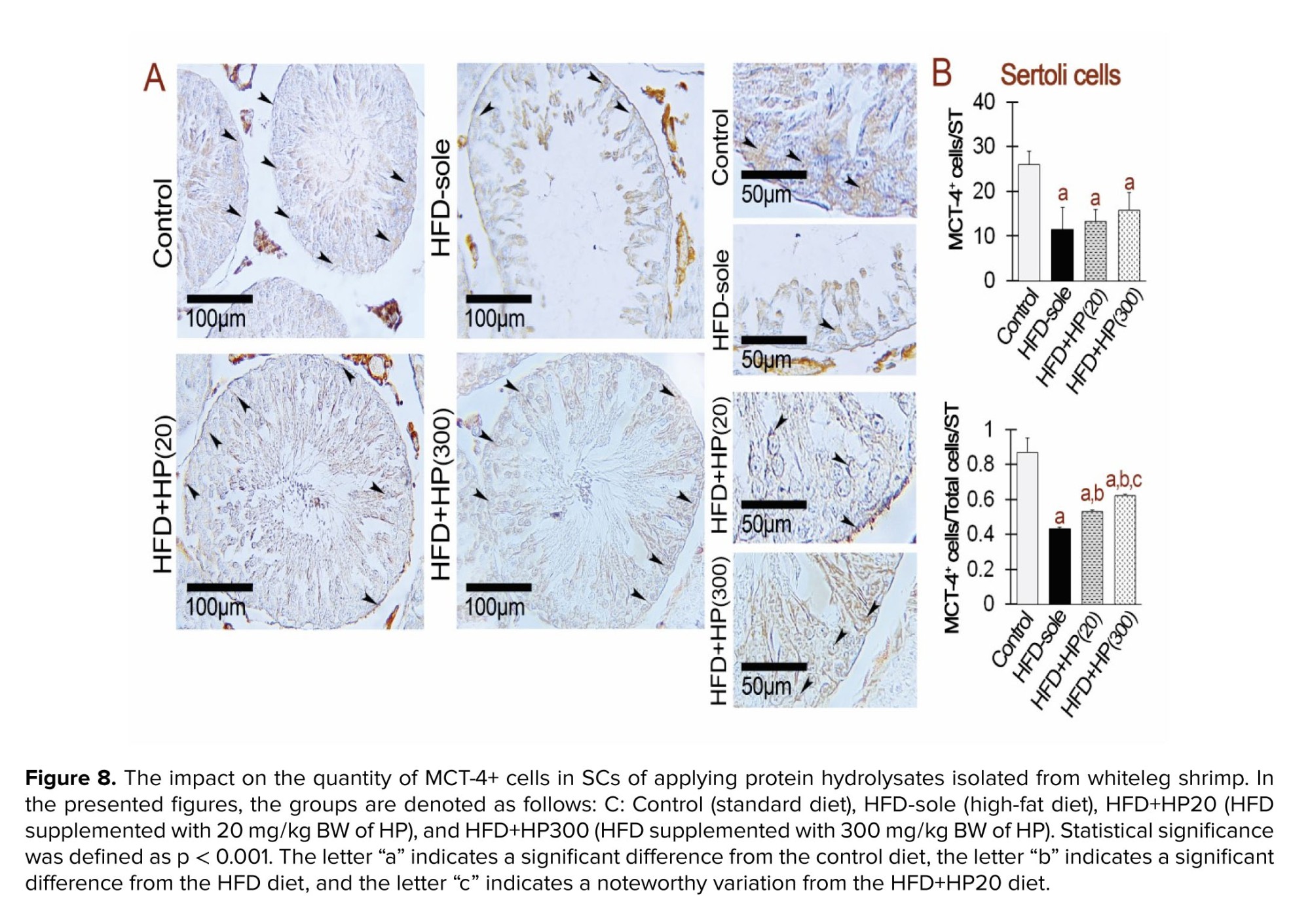

3.6. HP increased MCT-1+ and MCT-4+ cells in the testis

Figure 7 indicates the effects of HPs on MCT-1⁺ expression in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and SCs. In spermatogonia, both HFD and HP treatments induced a significant reduction in MCT-1⁺ expression compared with the control group (p < 0.001), with no significant differences between HFD and HP-treated rats (p > 0.001). Interestingly, HFD+HP300 significantly increased MCT-1⁺ expression relative to all other experimental groups (p < 0.001). Figure 8 shows that MCT-4⁺ expression in SCs was significantly reduced in all dietary groups compared with the control (p < 0.001). HP supplementation increased MCT-4⁺ expression relative to HFD (p < 0.001), although levels remained markedly lower than in the control group (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study investigated NAFLD model treated with different doses of HP. We focused on OS from the HFD, the changes in transporters (GLUT-1, GLUT-3, MCT-1, MCT-4), and some key genes related to autophagy (Beclin-1, LC3-I, Atg7, p62). We also checked histomorphometry, like the number of Leydig cells and SCs, tubular diameter, and TDI and SPI indexes, before and after HP treatment. The HFD group showed severe OS, higher expression of autophagy genes, and lower levels of transporter proteins. In contrast, HP treatment helped to balance the redox system, reduced autophagy gene expression, and increased transporter expression.

Results showed that structural damage to the spermatogenic epithelium was indicated by lowering of seminiferous tubular diameter, SCs number, TDI and SPI index values in HFD group. Tubular diameter is a well-established indicator of seminiferous tubule integrity and germ cell population, and when it decreases, it is typically associated with germ cell loss as well as a decline in sperm output (22). Likewise, SCs provide all the energy and paracrine support needed by developing germ cells, so if they are destroyed, lactate supply will decline too; as a result, differentiation becomes unfavorable to these immature cells. TDI and SPI are functional readouts of spermatogenesis efficiency. A low TDI means germ cells cannot follow through with differentiation, while a reduced SPI reflects disrupted spermiogenesis and release of fully formed spermatozoa (15, 23). Hence, the upgrading in tubular diameter, SCs number, TDI and SPI after HP treatment demonstrates that HPs restore not only redox balance and transporter expression profiles but also the framework of the seminiferous epithelium. This structural preservation is crucial for maintaining reproductive potential, because it safeguards an ample supply of metabolic energy from SCs to germ cells as well as the ability of these cells to progress successfully through spermatogenesis.

NAFLD has been associated with an increased accumulation of lipid in the liver, boosting ROS levels and disrupting redox balance (6). Indeed, the imbalance between the redox system and oxidants in the testicles has been shown to induce OS or RS in the testicles, crucially impacting physiologic interactions (21). In line with this issue, the key characteristics of RS include no significant changes in tissue/serum TAC level, a sharp increase in GSH levels, a changed GSH to GSSG ratio, and an elevated MDA content, pointing toward lipid peroxidation (24). In light of these phenotypes, we found a pronounced increase in testicular GSH and MDA levels in the HFD-sole group without any significant changes in TAC level. Conversely, HP supplementation improved these parameters. Specifically, the HFD+HP300 group showed reduced MDA and GSH levels and an improved GSH/GSSG ratio, suggesting ameliorated reductive stress (RS). Our recent findings corroborate previous reports indicating the antioxidant properties of HPs, which enable these agents to protect cellular DNA content against free radicals (8, 25, 26). By integrating our results with earlier findings about the protective effect of HPs on the redox system, we propose that HPs, especially in the HP300-treated group, can reduce oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation caused by HFD-induced ROS in the testicles by improving RS.

It has been well established that the redox system failure in testicular tissue can significantly impact the initiation of autophagy. Indeed, the imbalance between ROS and redox antioxidant defense system leads to RS and OS, key triggers for autophagy (27, 28). Accordingly, elevated ROS levels can damage cellular backbone components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, prompting the cell to initiate autophagy as a protective mechanism (29). Beclin-1, LC3-I, Atg7, and p62 are among the autophagy-related genes that are activated during this process. Autophagosomes are formed to break down and recycle damaged cellular components (27). In this context, it is important to highlight that phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, produced by the Beclin-1 complex, initiates the formation of autophagosomes. Moreover, Atg7 contributes to the lipid conjugation of LC3-I and the elongation of the autophagosome membrane in conjunction with other proteins (30). To finalize the formation of autophagosomes, LC3-I (the free form) is ultimately converted into LC3-II (the lipid-conjugated form) (31). Therefore, assessing changes in the expression levels of LC3-I/II and Atg7 is essential for exploring autophagy-related reactions. In line with this issue, we utilized IHC staining to determine alterations associated with LC3-I/II, a crucial autophagy marker, and measured the mRNA levels of Beclin-1 and Atg7, the key facilitator of autophagosome formation. The HFD-sole group showed a remarkable increase in the mean Beclin-1, Atg7, and LC3-I/II expressions vs. the control group. Moreover, the mean expression of the p62 was increased in the same rats. In fact, p62 is a substrate for autophagy that was employed as a reporter to target certain payloads for autophagy (32). The increased expression of p62 following HFD induction, coupled with elevated expression of LC3-I/II, suggests an accumulation of damaged cargoes in testicular tissue that are moving to be eliminated by autophagy. Furthermore, the synchronization of these changes with HFD-induced RS indicates that HFD can initiate autophagy through inducing RS in the testicles. To have a better understanding of the issue, one should be aware that Atgs primarily affect the control of autophagy gene expression (33). The activities of Atgs are significantly influenced by 2 key players: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and Forkhead box O. These factors respond to changes in OS and play a vital role in managing and creating autophagosomes (34). These transcription factors act like molecular switches, regulating Atg synthesis and the start and progression of autophagy (24).

Previous research has demonstrated that metabolic disorders, including diabetes and NAFLD, induce OS within the testes, subsequently disrupting autophagy primarily via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway (35, 36). This maladaptive autophagic response exacerbates oxidative damage and apoptosis in both germ and SCs, thereby impairing spermatogenesis and compromising the structural and functional integrity of the testes. As mentioned earlier, glucose transporters (GLUT-1, GLUT-3) and lactate transporters (MCT-1, MCT-4) are crucial for keeping metabolic balance in testicular tissue (15, 37). Disruption in their expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels, can detrimentally affect the transition of energy substrates, leading to metabolic OS and subsequent activation of autophagy pathways (27). In light of these considerations, we evaluated the mean distributions of GLUTs+ and MCTs+ cells in testicular tissue using IHC analysis. The HFD-sole group exhibited a significant reduction in the mean distribution of GLUTs (1 and 3) and MCTs (1 and 4) compared to the control group, a trend that was reversed in the HP-treated groups (HFD+HP20 and HFD+HP300). These changes were more prominent in the HFD+HP300 group. Nutritional status appears to be an important determinant, as reported in previous studies (38, 39). Their findings indicate that HFD and diabetes induce insulin resistance, escalate OS, and thereby, negatively impact energy transporters expression levels, particularly GLUT1, GLUT3 as well as lactate transporters MCT1, MCT4. Furthermore, their findings demonstrated that the administration of bee bread in obese rats and Gum Arabic in diabetic rats mitigated insulin resistance and decreased OS, thereby enhancing the expression of energy transporters in the testes of the studied rodents. Based on our findings, we can suggest that HFD-induced changes in GLUTs and MCTs may disrupt the metabolomic transition, leading to massive alterations in the redox system that can, in turn, end up with RS in the testicles. Thereafter, the RS can trigger autophagy pathways. Considering that the HFD-only group showed poor spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis, as indicated by TDI and SPI, while the HP-treated groups experienced improved TDI and SPI, it is clear that HP treatment, especially HP300, has a positive impact. This improvement is accompanied by a restored redox balance and reduced levels of autophagy markers in the HP-treated groups. Therefore, we can conclude that HP, particularly HP300, has the potential to boost germ cell growth and development by enhancing the redox system and managing autophagy in testicular tissue.

5. Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that HP treatment effectively ameliorated HFD-induced conditions in the testicles, as evidenced by the restoration of redox balance and the suppression of autophagy markers, particularly in the high concentration of HP (300 mg). Importantly, our study suggests that HP, particularly HP300, holds promise for enhancing germ cell proliferation and differentiation by modulating metabolomics transition, bolstering the redox system, and regulating eliminative autophagy in testicular tissue. These findings highlight how essential maintaining redox balance and metabolic regulation is for testicular health.

Data Availability

The individual responsible for the study and in possession of the complete dataset is Dr. Ebrahim Najdegerami.

Author Contributions

S. Javanmard designed and executed the practical experiments. E. Najdegerami and M. Razi contributed to the study design, supervised the research process, and performed the data analysis. M. Nikoo was responsible for the preparation of bioactive peptides. S. Javanmard wrote the manuscript, and E. Najdegerami, M. Razi, and M. Nikoo participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and are accountable for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Urmia University, Urmia, Iran (grant number: 5702). Additionally, the authors used ChatGPT AI solely for grammatical corrections, not for generating content, in certain sections of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by excessive hepatic lipid accumulation and may progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, or cancer (1). Oxidative stress (OS) is central to NAFLD pathogenesis (2) and causes Sertoli and germ cell dysfunction (3). NAFLD-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase lipid peroxidation and disrupt spermatogenesis (4). Approximately 40% of infertile men are affected by NAFLD (5). Since no specific treatment exists and chemical drugs often cause adverse effects, alternative strategies are being investigated, including natural antioxidants such as bioactive peptides, which have shown potential to mitigate OS and improve liver health.

Bioactive peptides are extracted from different protein sources using proteolytic enzymes and typically consist of 2-22 amino acids in their structure. Their antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory properties (6), and manipulation of cellular signaling pathways (7) are some of the proposed underlying processes. These peptides lessen OS, inflammation, and maintain cellular integrity, perhaps defending the function of the testicles under stressful situations (8). However, the precise effects might vary depending on the HPs composition and source, indicating the need for more study to completely understand these pathways.

Seminiferous tubules, the functional units of spermatogenesis, are composed of germ cells and Sertoli cells (SCs) (9). SCs regulate germ-cell development through structural, metabolic, and immunological functions (10) and their interactions with germ cells are highly vulnerable to inflammatory, oxidative, and hormonal disturbances (9). Glucose uptake by SCs occurs via GLUT-1 and GLUT-3, after which glucose is converted to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase; this lactate serves as the primary energy source for germ cells and is exported through MCT-4 and taken up by MCT-1 in spermatogonial cells (11). Despite expressing GLUTs and glycolytic enzymes, germ cells depend on SCs for nutrient supply (12). SC metabolism (including lactate synthesis and MCT-4 expression) is further shaped by growth factors, cytokines, and steroid hormones (13, 14). Evidence indicates that NAFLD disrupts GLUT1, GLUT3, and MCT4 activity in rat Sertoli and germ cells, thereby altering testicular glucose transport and energy homeostasis (15, 16).

OS also modulates the expression of autophagy-related genes in the testes. Autophagy, a central degradative pathway, is activated in response to oxidative injury and contributes to testicular homeostasis. Key autophagy regulators, including microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and Beclin-1, are upregulated in SCs to support germ-cell survival and differentiation under stress conditions (17).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the protective effects of whiteleg shrimp bioactive peptides against NAFLD-induced testicular dysfunction. Unlike prior work focused mainly on hepatic parameters, the present investigation examines testicular redox balance, autophagy-related gene expression, and the distribution of major energy-transport proteins (GLUT1, GLUT3, MCT1, and MCT4) in Sertoli and germ cells. By combining biochemical measurements with morphometric and histological analyses, such as seminiferous tubule diameter, SCs counts, tubular differentiation index (TDI), and spermiogenesis index (SPI), this study provides new insights into how shrimp peptides help preserve spermatogenesis and testicular structure under metabolic stress. Accordingly, we aimed to determine the effects of HPs on OS, autophagy-related gene expression, and key energy transporters (GLUT-3, GLUT-1, and MCT-4) in NAFLD-associated testicular dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioactive peptides preparation

Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) processing by-products were obtained from Daryahodeh Co. (Bushehr, Iran) and subsequently delivered to the Artemia and Aquaculture Research Institute at Urmia University, Urmia, Iran for further analysis. The by-products were subsequently comminuted using a 3 mm grinder (Pars Khazar Co., Tehran, Iran) and homogenized with distilled water in a 1:1 weight-to-volume ratio for 2 min using a Heidolph DIAX900 homogenizer (Heidolph Instruments GmbH, Schwabach, Germany). Alcalase enzyme hydrolysis of the homogenized mixture was conducted at 40°C for 3 hr, maintaining an initial pH of 7.1. The homogenate was continuously stirred throughout the hydrolysis. Following hydrolysis, the reaction was terminated by incubation in a boiling water bath (95°C) for 10 min. The mixture was then filtered through cheesecloth, followed by centrifugation (4000 g, 20 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was subsequently lyophilized. Analysis of the resulting bioactive peptides revealed a distribution of peptide chain lengths following hydrolysis. Notably, approximately 40% of the total peptides exhibited a molecular weight below 500 Da (18) (Figure 1).

2.2. Experiment design, animals, and diets

In this experimental study, 24 male Wistar rats, weighing an average of 230.2 ± 23 gr (8 wk) at the start of the experiment, were obtained from the Department of Biology (Urmia University, Urmia, Iran). The rats were housed in groups of 6 under controlled conditions (25°C, 12-hr light/dark cycle) and acclimated to a standard chow diet for a week. The rats were randomly allocated to one of 4 experimental groups once they had acclimated: control (standard chow diet), HFD-sole (high-fat diet), HFD+HP20 (high-fat diet supplemented with 20 mg/kg BW bioactive peptides), and HFD+HP300 (high-fat diet supplemented with 300 mg/kg BW bioactive peptides) (19) and fed for 10 wk. The HFD was formulated by enriching a standard chow diet with 10% animal fat and 5% fructose.

Freshly prepared HPs were diluted daily in 4 ml of distilled water at designated concentrations (20 and 300 mg/kg BW) and administered orally to the rats in the HFD+HP groups using an oro-gastric feeding tube. The control group received a standard chow diet and 4 ml of distilled water via the same route.

2.3. Tissue preparation and histological analysis

To guarantee minimal stress during the procedure of blood sample and biopsy, the rats were humanely put to sleep using an overdose of sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (90 mg/kg). The tissues of the right testicles were removed, preserved in Bouin's solution, subjected to standard processing, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned using a rotary microtome (LKB, UK) at a thickness of 5 µm. Tissue slices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological examinations. Stained slides were examined under light microscopy (Leica, Germany) at various magnifications (200x, 400x, and 1000x) to assess seminiferous tubule morphology. For each animal (n = 5), 30 seminiferous tubules were evaluated across 5 tissue sections. Spermatogenesis efficiency was quantified using the SPI and the percentage of seminiferous tubules exhibiting a positive TDI. A positive TDI score signifies the presence of > 3 distinct germ cell layers within a seminiferous tubule. Evaluation adhered to established criteria for identifying spermatogenic stages within the tubules (20).

2.4. OS

To assess total antioxidant capacity (TAC), testicular tissue homogenates were subjected to a colorimetric assay. Protein content was determined using Lowry's method. TAC results were normalized to protein content. The ferric reducing antioxidant power assay was employed to evaluate the tissue's capacity to reduce ferric ions. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, an indicator of lipid peroxidation, were quantified using a thiobarbituric acid reactants assay (Arsam Fara Biot, Iran). Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels were determined using a 5,5'-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid based assay (Arsam Fara Biot, Iran), while oxidized glutathione (GSSG) was measured using a glutathione test kit (Navand Salamat, Iran). Absorbance measurements were taken at the specified wavelengths (412 nm).

2.5. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted from testicular tissue using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and assessed for quality and quantity using spectrophotometry. Only high-quality RNA samples were used for cDNA synthesis, which was performed using a commercially available reverse transcription kit. qRT-PCR was conducted on a MyGo PCR thermal cycler (Life Technologies) using SYBR green master mix (mention brand name and supplier) and gene-specific primers (Table I). GAPDH served as the internal control for calculating the relative gene expression levels using the 2^-ΔCt technique (21).

2.6. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Following preparation, heating, deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval, tissue slices were used for IHC procedures. The primary antibody (Elabsciences, USA) was added to the tissue sections and left in contact with them under controlled conditions (overnight at 4°C) so that the antibody could bind to its target antigens in the tissue. After that slides were treated for an hour at 37°C with a secondary antibody. Hematoxylin & Eosin was used to stain nuclei, and diamethybenzidine was used to stain proteins. Serving as a negative control was normal IgG. The presence of LC3-I/II+ protein was shown by brown stains. In the end, 20 seminiferous tubules were chosen per cross-section for the purpose of counting LC3-I/II+ cells, and these cells were then counted per one seminiferous tubule (ST, 3 sections/animal; in total: 18 sections/group). Also, for IHC staining of GLUT1 (spermatogonia, SCs), GLUT3 (spermatogonia, spermatocyte, SCs), MCT-1 (spermatogonia, spermatocyte, SCs), and MCT-4 (SCs) proteins, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies (Elabsciences, USA), anti-GLUT-3 antibody (Elabsciences, USA), and anti-MCT-4 antibody (Elabsciences, USA). The LC3-I/II protein expression analysis criteria were also utilized to assess the expression of the MCT-1, MCT-4, GLUT1, and GLUT3 proteins (15).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Urmia University, Urmia, Iran, for the care and handling of laboratory animals (Code: IR-UU-AEC-32108).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 20.0). The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were evaluated through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene's test, respectively. Group comparisons to identify statistically significant differences were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc multiple comparison tests, including Tukey’s honestly significant difference or Dunnett’s test, as deemed appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. HPs and an imbalanced redox system in the testis

Table II presents the OS indices across experimental groups. Testicular TAC remained unchanged among treatments. The HFD-sole group showed a significant elevation in MDA levels compared with the control (p < 0.001), whereas both HP-treated groups (HFD+HP20 and HFD+HP300) exhibited significantly lower MDA content (p < 0.001). MDA values in peptide-receiving rats did not differ from the control. In the HFD-sole group, GSH levels increased and GSSG levels decreased compared to control, leading to a reduced GSH/GSSG ratio. HP supplementation normalized GSH, GSSG, and the GSH/GSSG ratio, with the most pronounced recovery observed in the HFD+HP300 group.

3.2. Effects of HP on germ cell differentiation and spermatogenesis ratios

Figure 2 shows the influence of HP on Leydig and SC counts, as well as seminiferous tubule morphology. The HFD-sole group exhibited the smallest seminiferous tubule diameter and lowest SCs count, significantly differing from the control group (p < 0.01). Conversely, HP supplementation significantly increased seminiferous tubule diameter and SC numbers compared to the HFD-sole group (p < 0.01). While the number of Leydig cells remained comparable across all groups, the HFD-sole group demonstrated the highest levels of negative SPI and TDI, significantly differing from the control group (p < 0.01). HP administration significantly reduced these indices compared to the HFD-sole group (p < 0.01).

3.3. Impact of HP on autophagy gene expression in the testes

Figure 3 shows autophagy-related gene expression in testicular tissue. Both the HFD and HFD+HP20 groups showed significantly higher Beclin-1 and Atg7 expression than the control (p < 0.05), whereas HFD+HP300 significantly reduced their expression relative to the HFD group (p < 0.05). All treatments increased LC3 expression compared with the control (p < 0.05); however, LC3 levels in HFD+HP20 were significantly lower than in the HFD group (p < 0.05). No significant difference was detected between HFD+HP300 and HFD (p > 0.05). p62 expression decreased in all groups compared with control (p < 0.05). Although HP treatments lowered p62 relative to HFD, its levels remained above control values (p < 0.05).

3.4. LC3-I/II staining indicates autophagy activity in experimental treatments

To evaluate the effects of different diets on autophagy, we used immunohistochemistry to stain LC3-I/II+, which is a major indicator of autophagy completion (Figure 4). The results showed that rats given HFD had higher expression of LC3-I/II+/total cells/ST, which differed statistically significantly from the control group (p < 0.001). Moreover, in comparison to the HFD group, the administration of HP significantly reduced the expression of LC3-I/II+ (p < 0.001). It is remarkable, nonetheless, that the expression level continued to be much greater than that of the control group (p < 0.001), suggesting that HP had a major effect. Interestingly, no statistically significant difference was observed between the 2 treatment groups' bioactive peptides concentrations (p > 0.001).

3.5. Upregulated signals with GLUT1 and GLUT3 staining using HP

IHC analysis showed marked changes in GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression in spermatogonia (Figures 5 and 6). Both the HFD and HFD+HP20 groups exhibited significantly reduced GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression compared with the control (p < 0.001), whereas HFD+HP300 significantly increased their expression relative to HFD (p < 0.001) and restored levels comparable to control. In SCs, GLUT1⁺ and GLUT3⁺ expression was similarly decreased in the HFD group (p < 0.001), while both HP doses significantly enhanced expression compared with HFD (p < 0.001), reaching values indistinguishable from the control group.

3.6. HP increased MCT-1+ and MCT-4+ cells in the testis

Figure 7 indicates the effects of HPs on MCT-1⁺ expression in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and SCs. In spermatogonia, both HFD and HP treatments induced a significant reduction in MCT-1⁺ expression compared with the control group (p < 0.001), with no significant differences between HFD and HP-treated rats (p > 0.001). Interestingly, HFD+HP300 significantly increased MCT-1⁺ expression relative to all other experimental groups (p < 0.001). Figure 8 shows that MCT-4⁺ expression in SCs was significantly reduced in all dietary groups compared with the control (p < 0.001). HP supplementation increased MCT-4⁺ expression relative to HFD (p < 0.001), although levels remained markedly lower than in the control group (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study investigated NAFLD model treated with different doses of HP. We focused on OS from the HFD, the changes in transporters (GLUT-1, GLUT-3, MCT-1, MCT-4), and some key genes related to autophagy (Beclin-1, LC3-I, Atg7, p62). We also checked histomorphometry, like the number of Leydig cells and SCs, tubular diameter, and TDI and SPI indexes, before and after HP treatment. The HFD group showed severe OS, higher expression of autophagy genes, and lower levels of transporter proteins. In contrast, HP treatment helped to balance the redox system, reduced autophagy gene expression, and increased transporter expression.

Results showed that structural damage to the spermatogenic epithelium was indicated by lowering of seminiferous tubular diameter, SCs number, TDI and SPI index values in HFD group. Tubular diameter is a well-established indicator of seminiferous tubule integrity and germ cell population, and when it decreases, it is typically associated with germ cell loss as well as a decline in sperm output (22). Likewise, SCs provide all the energy and paracrine support needed by developing germ cells, so if they are destroyed, lactate supply will decline too; as a result, differentiation becomes unfavorable to these immature cells. TDI and SPI are functional readouts of spermatogenesis efficiency. A low TDI means germ cells cannot follow through with differentiation, while a reduced SPI reflects disrupted spermiogenesis and release of fully formed spermatozoa (15, 23). Hence, the upgrading in tubular diameter, SCs number, TDI and SPI after HP treatment demonstrates that HPs restore not only redox balance and transporter expression profiles but also the framework of the seminiferous epithelium. This structural preservation is crucial for maintaining reproductive potential, because it safeguards an ample supply of metabolic energy from SCs to germ cells as well as the ability of these cells to progress successfully through spermatogenesis.

NAFLD has been associated with an increased accumulation of lipid in the liver, boosting ROS levels and disrupting redox balance (6). Indeed, the imbalance between the redox system and oxidants in the testicles has been shown to induce OS or RS in the testicles, crucially impacting physiologic interactions (21). In line with this issue, the key characteristics of RS include no significant changes in tissue/serum TAC level, a sharp increase in GSH levels, a changed GSH to GSSG ratio, and an elevated MDA content, pointing toward lipid peroxidation (24). In light of these phenotypes, we found a pronounced increase in testicular GSH and MDA levels in the HFD-sole group without any significant changes in TAC level. Conversely, HP supplementation improved these parameters. Specifically, the HFD+HP300 group showed reduced MDA and GSH levels and an improved GSH/GSSG ratio, suggesting ameliorated reductive stress (RS). Our recent findings corroborate previous reports indicating the antioxidant properties of HPs, which enable these agents to protect cellular DNA content against free radicals (8, 25, 26). By integrating our results with earlier findings about the protective effect of HPs on the redox system, we propose that HPs, especially in the HP300-treated group, can reduce oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation caused by HFD-induced ROS in the testicles by improving RS.

It has been well established that the redox system failure in testicular tissue can significantly impact the initiation of autophagy. Indeed, the imbalance between ROS and redox antioxidant defense system leads to RS and OS, key triggers for autophagy (27, 28). Accordingly, elevated ROS levels can damage cellular backbone components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, prompting the cell to initiate autophagy as a protective mechanism (29). Beclin-1, LC3-I, Atg7, and p62 are among the autophagy-related genes that are activated during this process. Autophagosomes are formed to break down and recycle damaged cellular components (27). In this context, it is important to highlight that phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, produced by the Beclin-1 complex, initiates the formation of autophagosomes. Moreover, Atg7 contributes to the lipid conjugation of LC3-I and the elongation of the autophagosome membrane in conjunction with other proteins (30). To finalize the formation of autophagosomes, LC3-I (the free form) is ultimately converted into LC3-II (the lipid-conjugated form) (31). Therefore, assessing changes in the expression levels of LC3-I/II and Atg7 is essential for exploring autophagy-related reactions. In line with this issue, we utilized IHC staining to determine alterations associated with LC3-I/II, a crucial autophagy marker, and measured the mRNA levels of Beclin-1 and Atg7, the key facilitator of autophagosome formation. The HFD-sole group showed a remarkable increase in the mean Beclin-1, Atg7, and LC3-I/II expressions vs. the control group. Moreover, the mean expression of the p62 was increased in the same rats. In fact, p62 is a substrate for autophagy that was employed as a reporter to target certain payloads for autophagy (32). The increased expression of p62 following HFD induction, coupled with elevated expression of LC3-I/II, suggests an accumulation of damaged cargoes in testicular tissue that are moving to be eliminated by autophagy. Furthermore, the synchronization of these changes with HFD-induced RS indicates that HFD can initiate autophagy through inducing RS in the testicles. To have a better understanding of the issue, one should be aware that Atgs primarily affect the control of autophagy gene expression (33). The activities of Atgs are significantly influenced by 2 key players: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and Forkhead box O. These factors respond to changes in OS and play a vital role in managing and creating autophagosomes (34). These transcription factors act like molecular switches, regulating Atg synthesis and the start and progression of autophagy (24).

Previous research has demonstrated that metabolic disorders, including diabetes and NAFLD, induce OS within the testes, subsequently disrupting autophagy primarily via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway (35, 36). This maladaptive autophagic response exacerbates oxidative damage and apoptosis in both germ and SCs, thereby impairing spermatogenesis and compromising the structural and functional integrity of the testes. As mentioned earlier, glucose transporters (GLUT-1, GLUT-3) and lactate transporters (MCT-1, MCT-4) are crucial for keeping metabolic balance in testicular tissue (15, 37). Disruption in their expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels, can detrimentally affect the transition of energy substrates, leading to metabolic OS and subsequent activation of autophagy pathways (27). In light of these considerations, we evaluated the mean distributions of GLUTs+ and MCTs+ cells in testicular tissue using IHC analysis. The HFD-sole group exhibited a significant reduction in the mean distribution of GLUTs (1 and 3) and MCTs (1 and 4) compared to the control group, a trend that was reversed in the HP-treated groups (HFD+HP20 and HFD+HP300). These changes were more prominent in the HFD+HP300 group. Nutritional status appears to be an important determinant, as reported in previous studies (38, 39). Their findings indicate that HFD and diabetes induce insulin resistance, escalate OS, and thereby, negatively impact energy transporters expression levels, particularly GLUT1, GLUT3 as well as lactate transporters MCT1, MCT4. Furthermore, their findings demonstrated that the administration of bee bread in obese rats and Gum Arabic in diabetic rats mitigated insulin resistance and decreased OS, thereby enhancing the expression of energy transporters in the testes of the studied rodents. Based on our findings, we can suggest that HFD-induced changes in GLUTs and MCTs may disrupt the metabolomic transition, leading to massive alterations in the redox system that can, in turn, end up with RS in the testicles. Thereafter, the RS can trigger autophagy pathways. Considering that the HFD-only group showed poor spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis, as indicated by TDI and SPI, while the HP-treated groups experienced improved TDI and SPI, it is clear that HP treatment, especially HP300, has a positive impact. This improvement is accompanied by a restored redox balance and reduced levels of autophagy markers in the HP-treated groups. Therefore, we can conclude that HP, particularly HP300, has the potential to boost germ cell growth and development by enhancing the redox system and managing autophagy in testicular tissue.

5. Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that HP treatment effectively ameliorated HFD-induced conditions in the testicles, as evidenced by the restoration of redox balance and the suppression of autophagy markers, particularly in the high concentration of HP (300 mg). Importantly, our study suggests that HP, particularly HP300, holds promise for enhancing germ cell proliferation and differentiation by modulating metabolomics transition, bolstering the redox system, and regulating eliminative autophagy in testicular tissue. These findings highlight how essential maintaining redox balance and metabolic regulation is for testicular health.

Data Availability

The individual responsible for the study and in possession of the complete dataset is Dr. Ebrahim Najdegerami.

Author Contributions

S. Javanmard designed and executed the practical experiments. E. Najdegerami and M. Razi contributed to the study design, supervised the research process, and performed the data analysis. M. Nikoo was responsible for the preparation of bioactive peptides. S. Javanmard wrote the manuscript, and E. Najdegerami, M. Razi, and M. Nikoo participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and are accountable for the integrity of the data.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Urmia University, Urmia, Iran (grant number: 5702). Additionally, the authors used ChatGPT AI solely for grammatical corrections, not for generating content, in certain sections of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Cellular and Molecular Biology of Reproduction

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |