Tue, Feb 17, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 11 (November 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(11): 867-880 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Malverdi N, Kazemi S, Tavakoli N, Deemeh M R, Abedinzadeh M, Vahidi S et al . A special perspective on human fertilization: The role of sperm capacitation proteins and channels: A narrative review. IJRM 2025; 23 (11) :867-880

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3646-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3646-en.html

Nasrin Malverdi1

, Sheida Kazemi2

, Sheida Kazemi2

, Negin Tavakoli3

, Negin Tavakoli3

, Mohammad Reza Deemeh3

, Mohammad Reza Deemeh3

, Mehdi Abedinzadeh4

, Mehdi Abedinzadeh4

, Serajoddin Vahidi5

, Serajoddin Vahidi5

, Peyman Salehi *6

, Peyman Salehi *6

, Sheida Kazemi2

, Sheida Kazemi2

, Negin Tavakoli3

, Negin Tavakoli3

, Mohammad Reza Deemeh3

, Mohammad Reza Deemeh3

, Mehdi Abedinzadeh4

, Mehdi Abedinzadeh4

, Serajoddin Vahidi5

, Serajoddin Vahidi5

, Peyman Salehi *6

, Peyman Salehi *6

1- Department of Cell and Molecular Biology and Microbiology, Faculty of Biological Science and Technology, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran.

3- Andrology Department, Nobel Mega-lab, Isfahan, Iran.

4- Department of Urology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Andrology Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

6- Andrology Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,dr_p_salehi@yahoo.com

2- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran.

3- Andrology Department, Nobel Mega-lab, Isfahan, Iran.

4- Department of Urology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

5- Andrology Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

6- Andrology Research Center, Yazd Reproductive Sciences Institute, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 614 kb]

(444 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (185 Views)

2.2. Data extraction

To identify research that specifically examined the function of particular proteins or channels in the physiological process of human sperm capacitation, the retrieved records were filtered by title and abstract. The eligibility of full-text publications of possibly pertinent research was then evaluated. To find any more relevant publications that might have been overlooked in the database search, the reference lists of important review articles and qualified primary research were searched manually.

3. Capacitation mechanism

One of the most significant changes occurs during capacitation when the cholesterol levels in the sperm membrane attenuate and drop (11). Many proteins serve as acceptors for cholesterol, allowing the substance to be transferred from the sperm membrane to the proteins themselves (12).

It is possible to think of these proteins as capacitation factors. When it is present in vivo, the lipid transfer protein I is a crucial cholesterol acceptor in the female reproductive system. Key proteins in this biological process include caveolin 1 and 2, flotillin 1 and 2, and several important gangliosides present in the membrane lipid rafts (13, 14). Interestingly, the albumin protein plays a crucial role as a cholesterol acceptor in both in vivo contexts, such as uterine and follicular fluids (15), and in vitro contexts, like culture media (12). Sperm capacitation is induced as a result of this disturbance of the cholesterol balance in the membrane, clustering of monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1), and aggregation of zona pellucida (ZP)-binding molecules (16, 17).

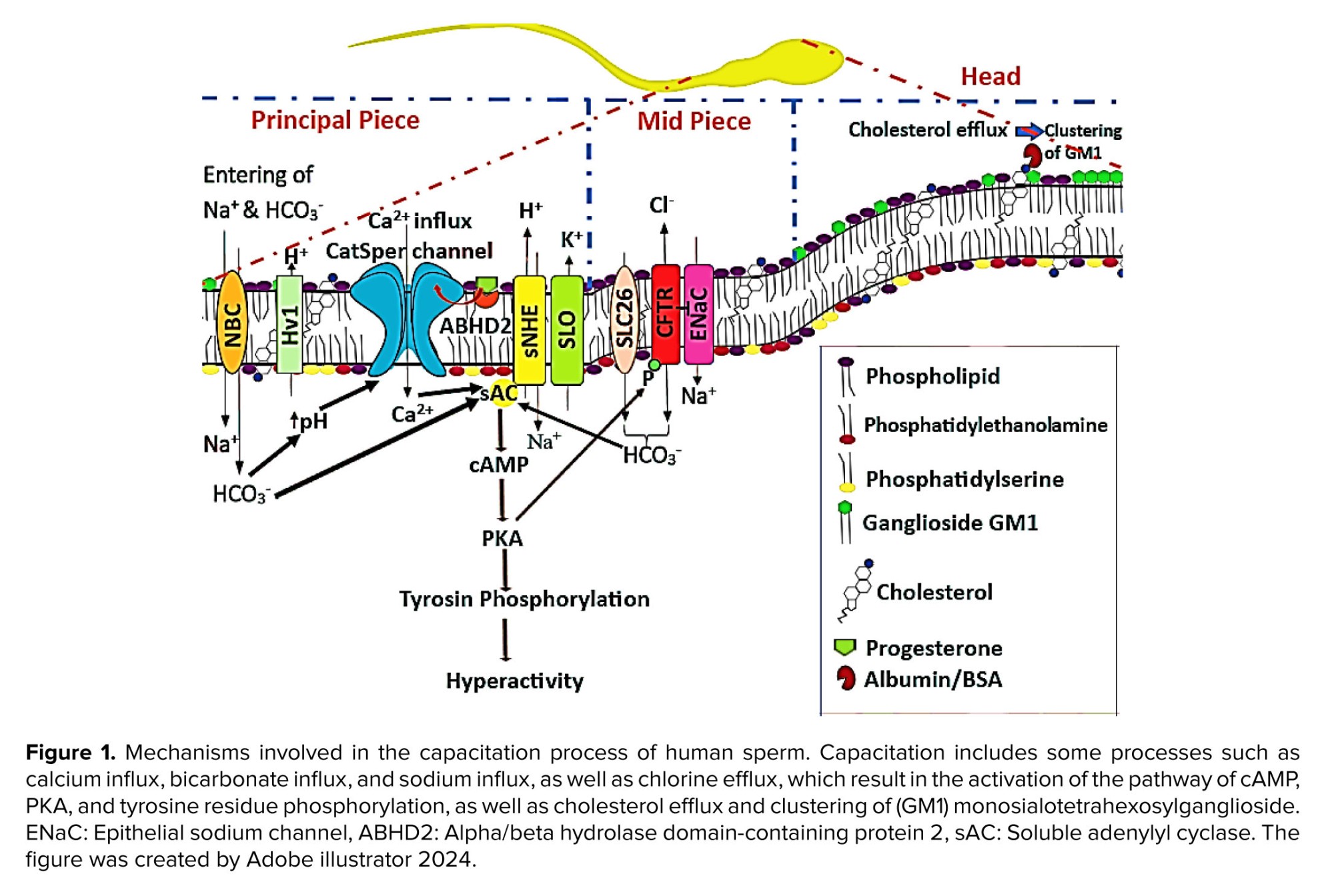

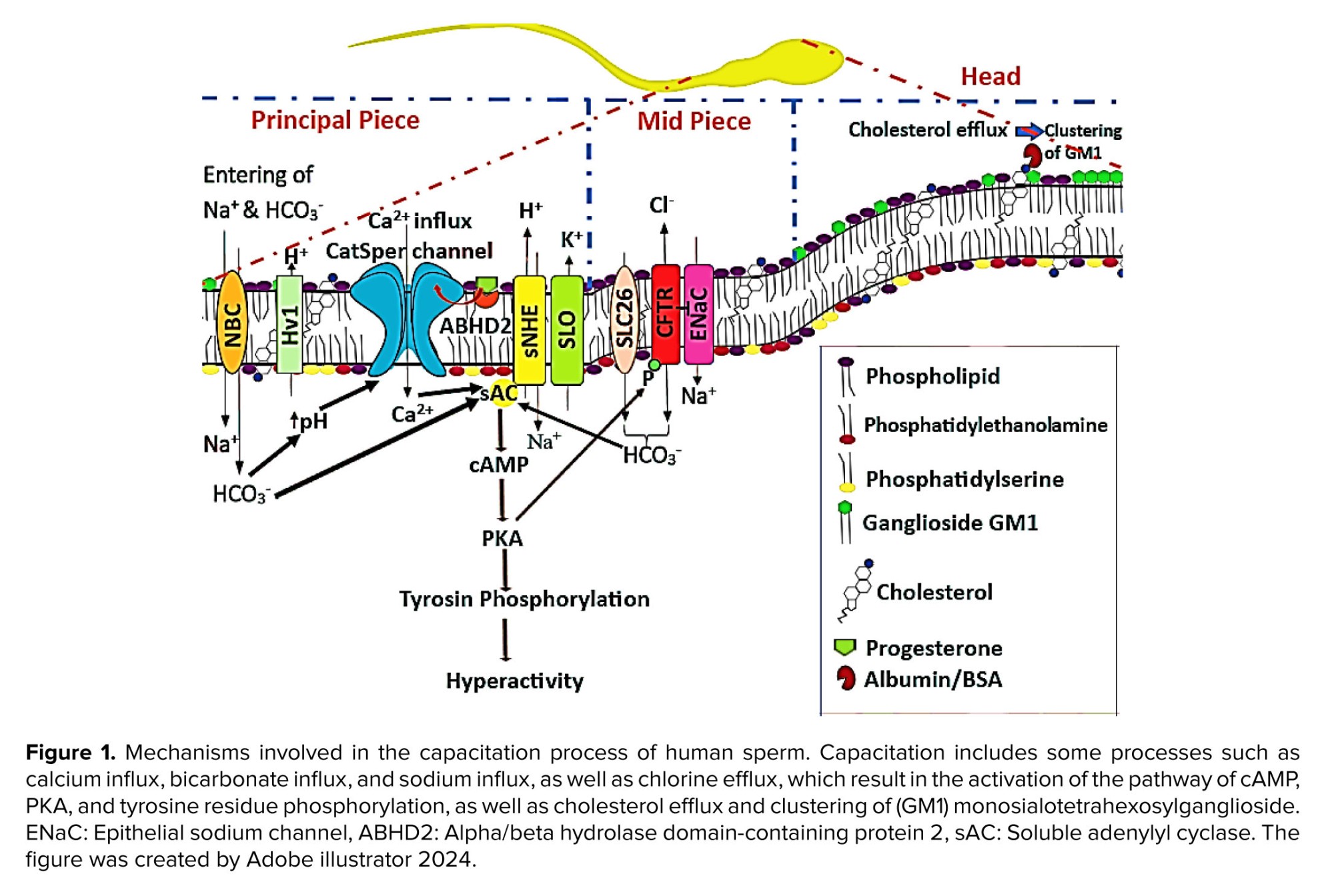

The concentration of electrolytes varies in the environments that sperm encounter during their migration into the oocyte. Variations in the amounts of intracellular and external electrolytes cause protein kinase activity to trigger the capacitation signaling pathway (18). As sperm approaches the egg, several electrolyte concentrations change, which surely affects the intracellular electrolyte concentration in the sperm. Furthermore, the specific channels in the sperm membrane that permit the passage of certain ions, like the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel (CFTR), Na+/HCO3- cotransporters (NBC), sperm specific Na+/H+ exchanger, and others, help regulate fluctuations in the concentrations of electrolytes (19). One important factor influencing the onset of capacitation signaling was elevated bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) concentrations. HCO3- is entered in the sperm by stimulating certain CFTR channels, particularly in the fallopian tube (20). Adenylate cyclase 10 is a solute found in the cytoplasm of sperm that is triggered instantly by an increase in HCO3- (21).

Intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) increases as a result of this mechanism (22). Proteins implicated in the capacitation route have their tyrosine residues phosphorylated by cAMP, which activates intracellular protein kinases, particularly protein kinase A (PKA) (23). PKA is more responsible for tyrosine residue phosphorylation of proteins involved in capacitation (24). Another electrolyte signaling pathway, induced capacitation, involves variations in hydrogen ion (H+) concentration or pH. Certain channels and the extracellular H+ concentration both affect pH control. Sperm pH regulation is mostly dependent on the bicarbonate exchange channels and the Na+/H+ exchanger, and also pH fluctuations depend on Hv families such as voltage-gated H+ channels (Hv1) (Figure 1) (25). The CFTR channel is one of the main HCO3- channels in sperm (26).

The CFTR interaction with solute carrier 26 channels (27, 28). One sign of cystic fibrosis, which is brought on by genetic anomalies in these channels, is the immobility of the sperm (29). Potassium ion (K+) channels, commonly referred to as calcium-activated potassium channel and 3 (K+ channels 1 and 3), are responsible for both causing and controlling pH changes (30). Sodium/potassium ATP pumps are also significant in this regard (18). Calcium is another essential electrolyte that helps with the initiation and progression of capacitation. Calcium can bind and strengthen binders found in several enzymes involved in the capacitation process (31) that lead to controls of the levels of key enzymes such as phosphatase, phosphodiesterase, adenylate cyclase, and protein kinases based on capacitation by binding calcium ion (Ca2+) to calmodulin receptors or in other ways (32).

Specific channels in sperm are responsible for transporting Ca2+, which precisely control their concentration. There are 2 main kinds of channels: the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase family, which releases calcium when ATP energy is present and stores it in cellular reservoirs (33); and the cation channels of sperm (CatSper) family, a significant family of voltage-dependent calcium channels that is crucial for supplying Ca2+and modifying the type of motility in sperm (34, 35). Particularly, CatSper 1, 2, and 4 are crucial in causing sperm capacitation by hyperactive motility (36). Sperm that do not have these channel genes are unable to produce agitated motions (18, 19). Figure 1 is a popular representation of the processes involved in human sperm capacitation. The remarks provided a summary of the molecular process of capacitation, with each pathway being covered in considerable depth.

4. Decapacitation factors

Although female vaginal tubes often include capacitation factors, there are occasionally outliers; seminal fluid generally contains decapacitation factors (9, 10). Sperm should not be kept capacitated in the seminal fluid for an extended period, as this might impair their physiological capacity to fertilize in a timely and suitable way (37). Semen includes a variety of proteins and non-protein components that help postpone early capacitation in addition to providing sperm with a nutritional environment that is conducive to their survival. Most of these substances preserve and stop the sperm membrane’s structure from altering in semen plasma. As majority of these chemicals are secreted by the accessory glands.

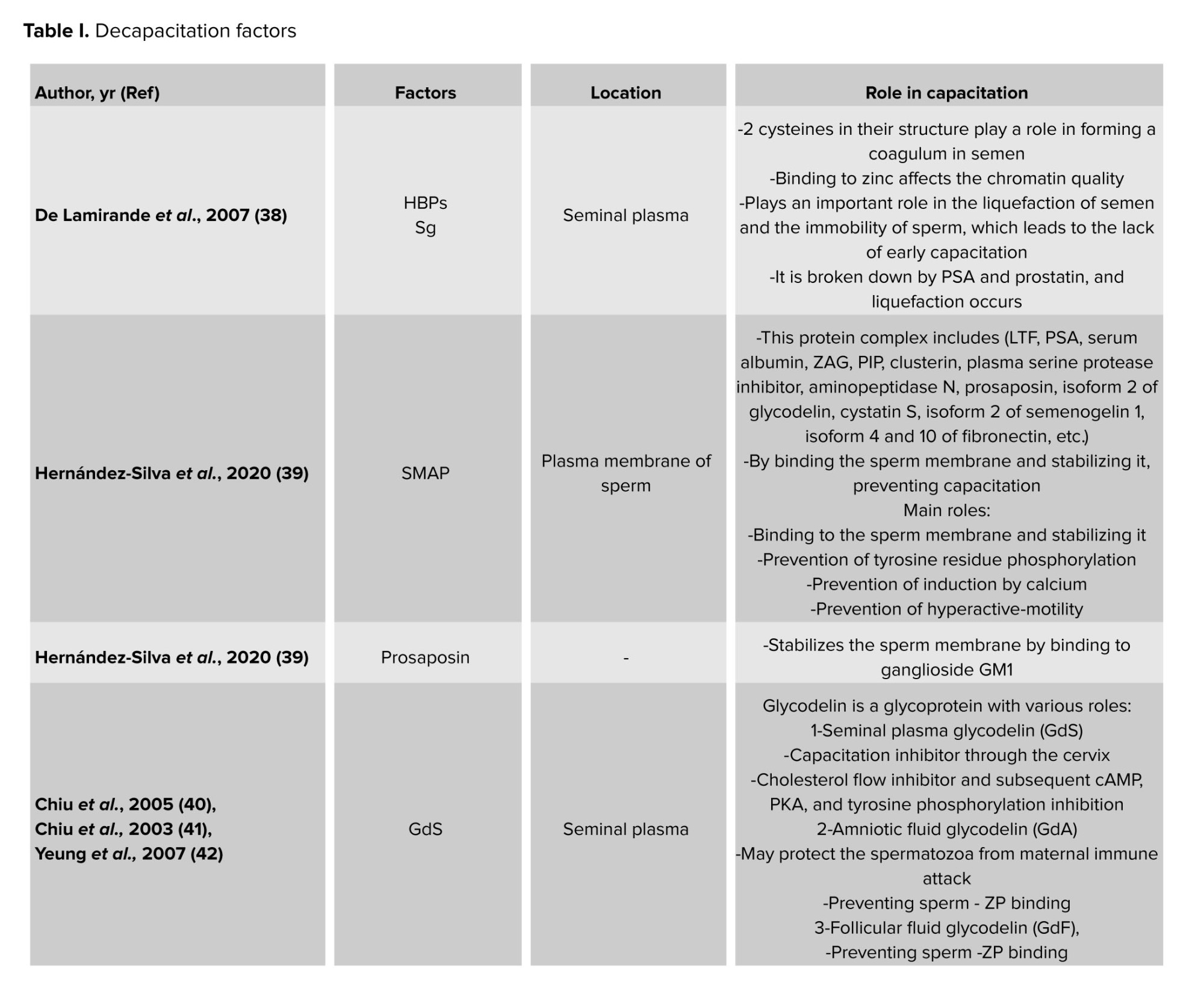

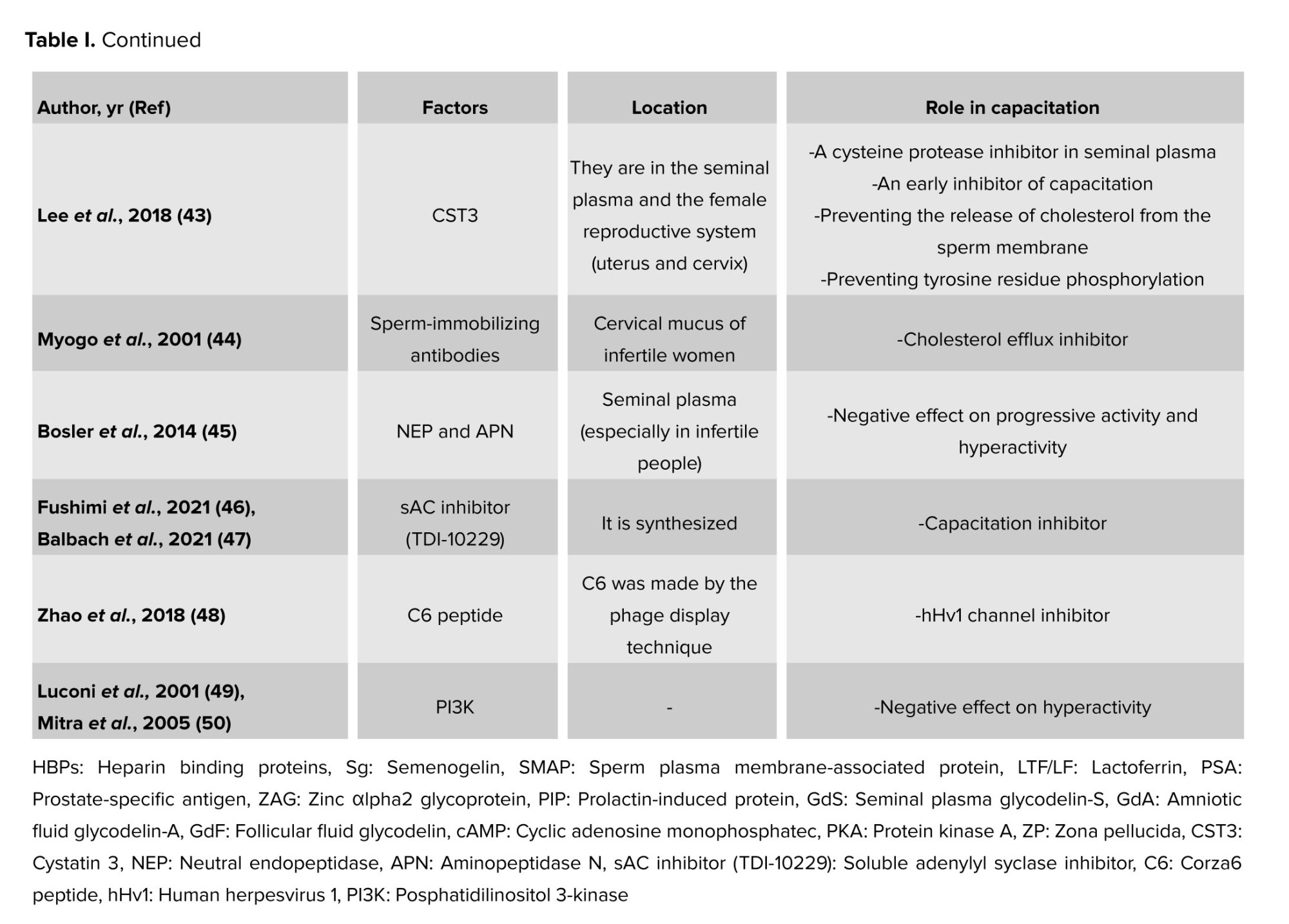

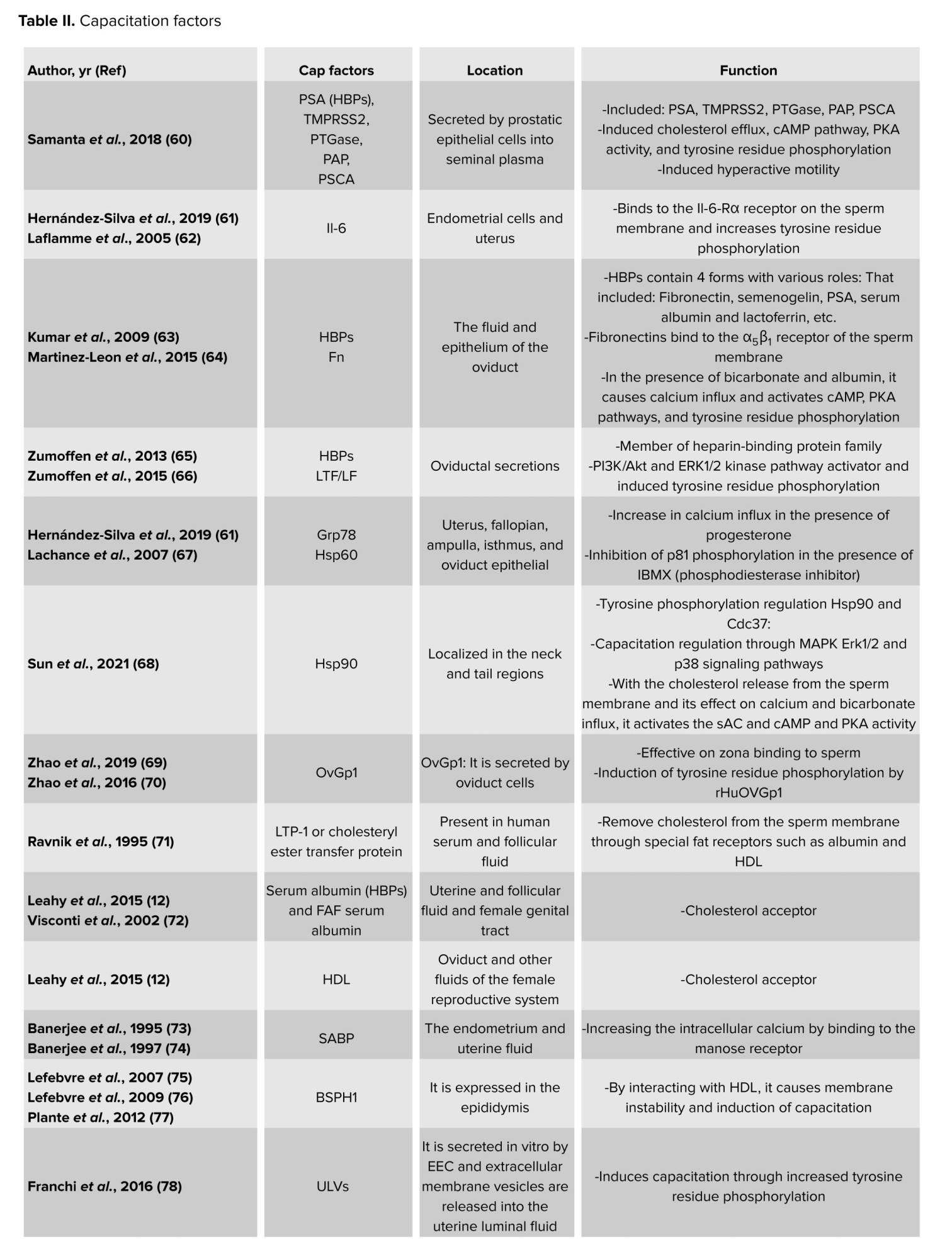

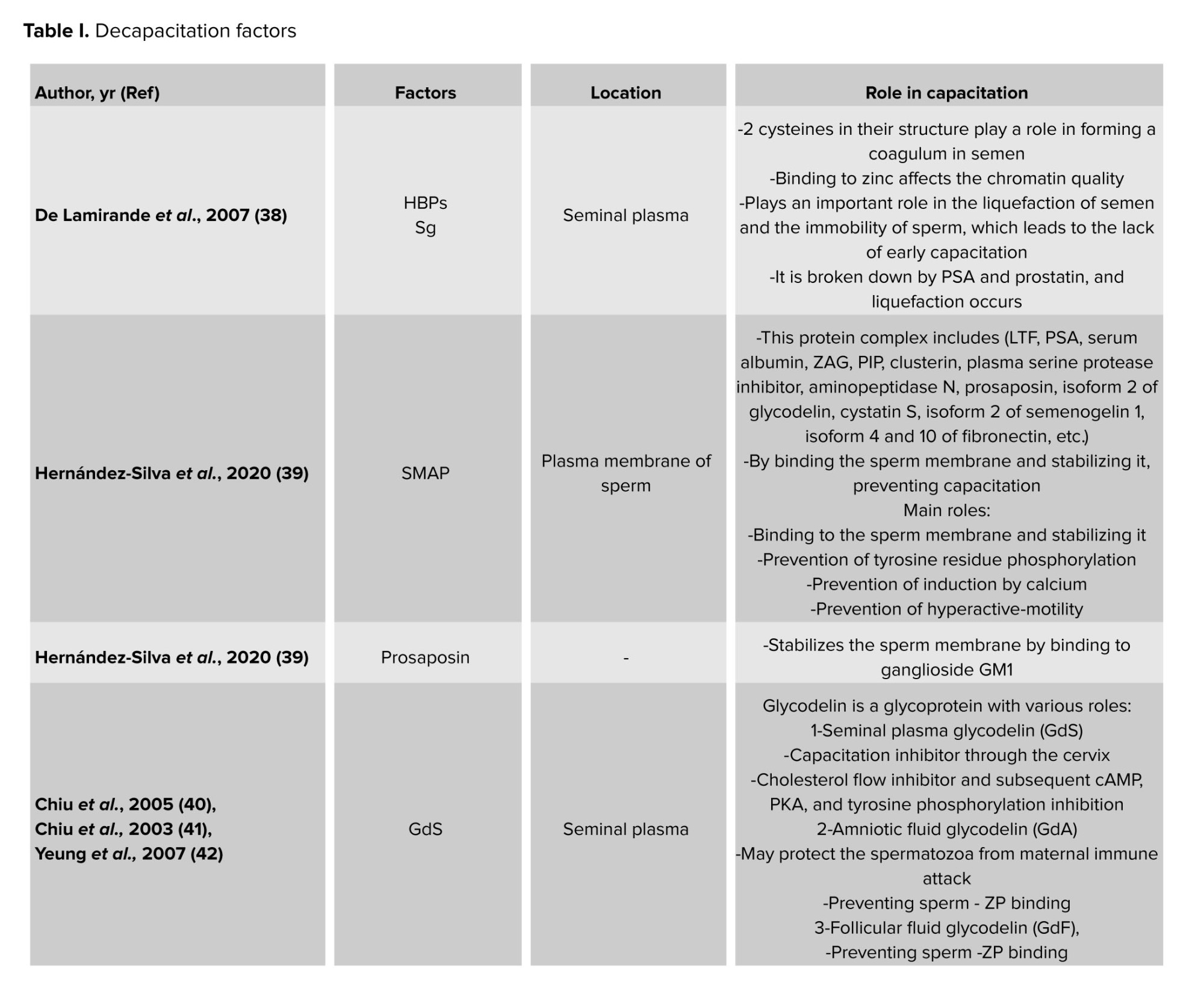

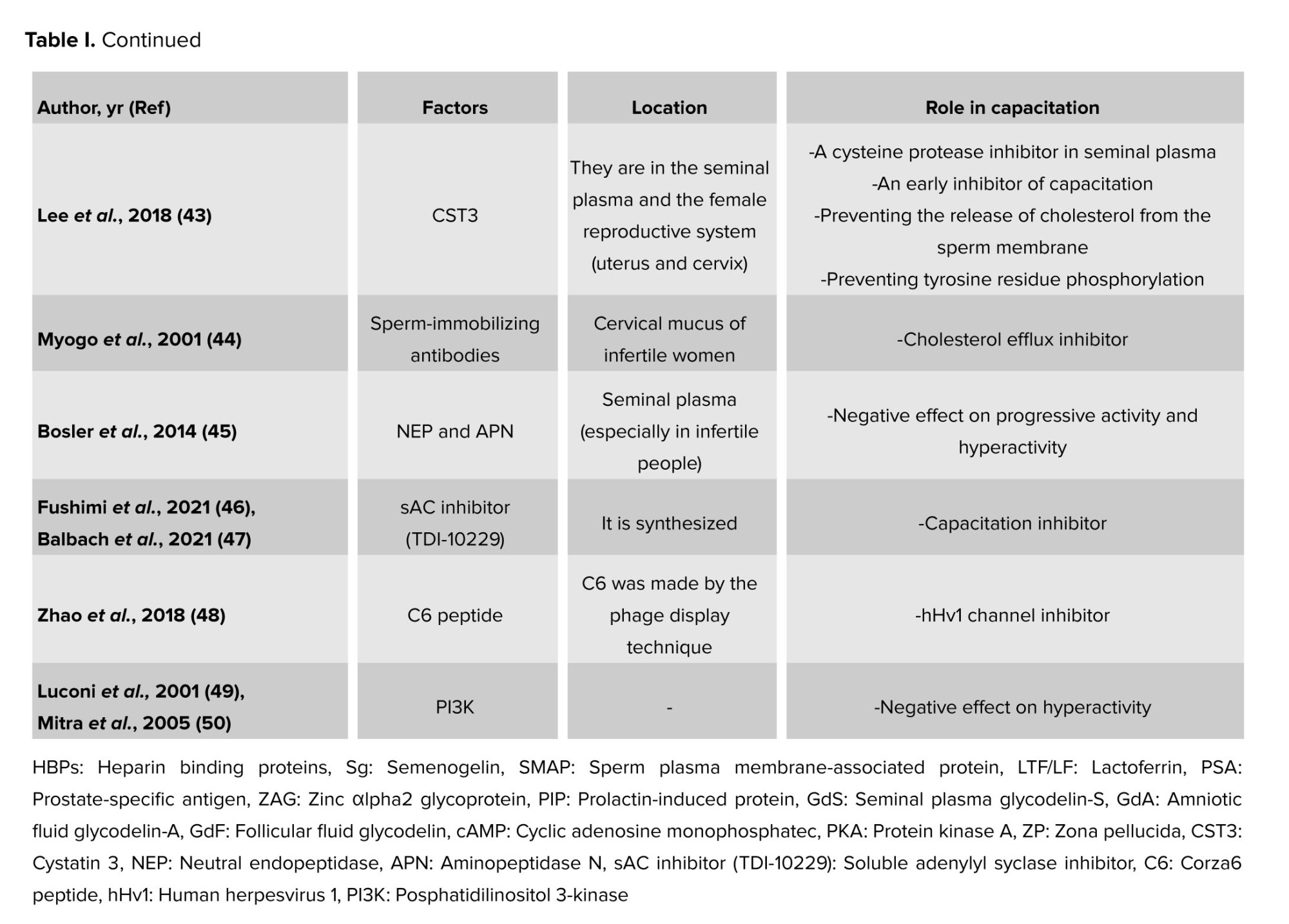

Nevertheless, some of these variables may also be involved in capacitation inhibition during sperm maturation because they have also been observed in the epididymis (8-10). A few of the crucial decapacitation protein factors are displayed in table I. The protein families that might have multiple proteins engaged in the decapacitation process are also included in this table.

5. Capacitation factors

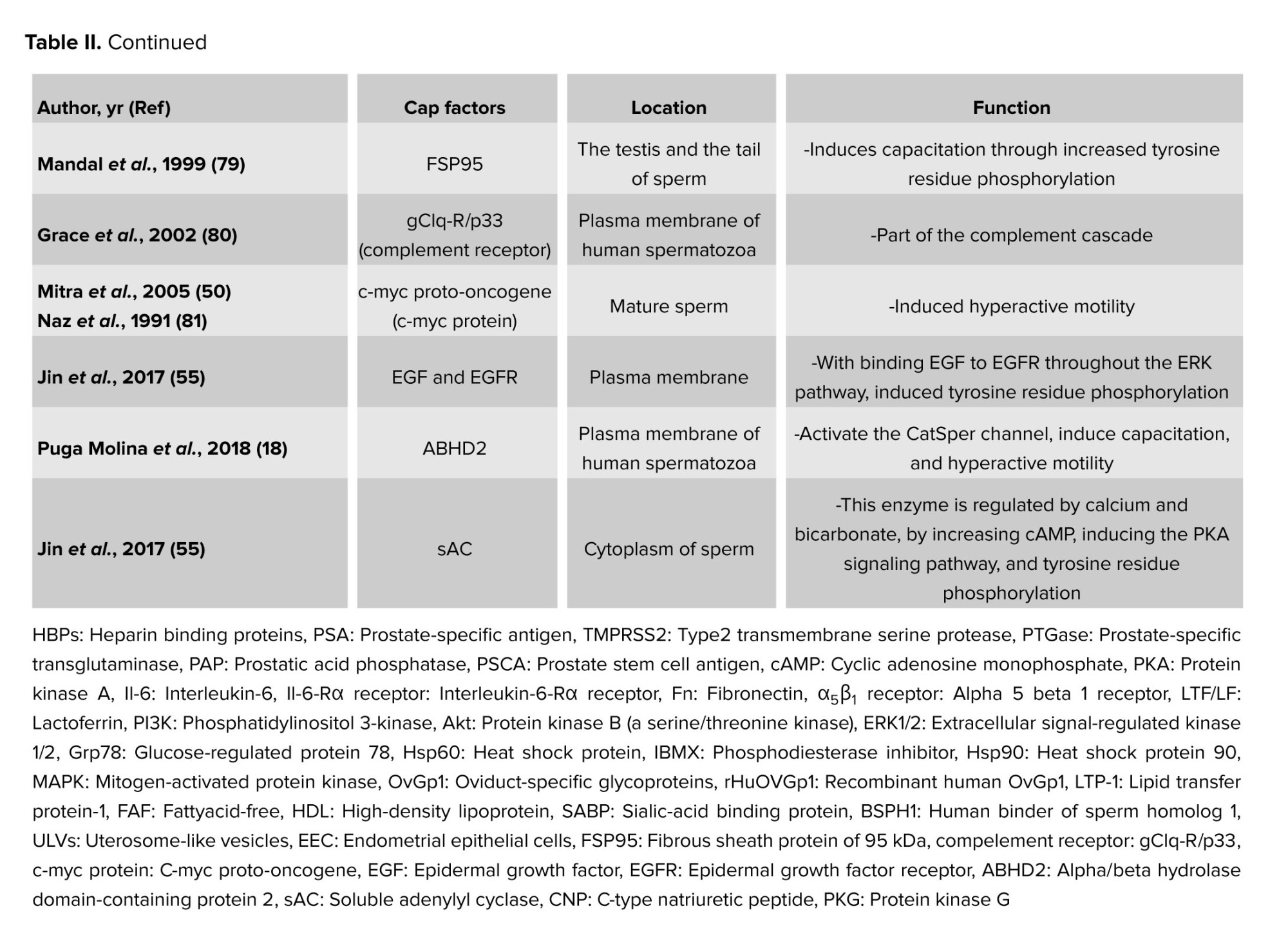

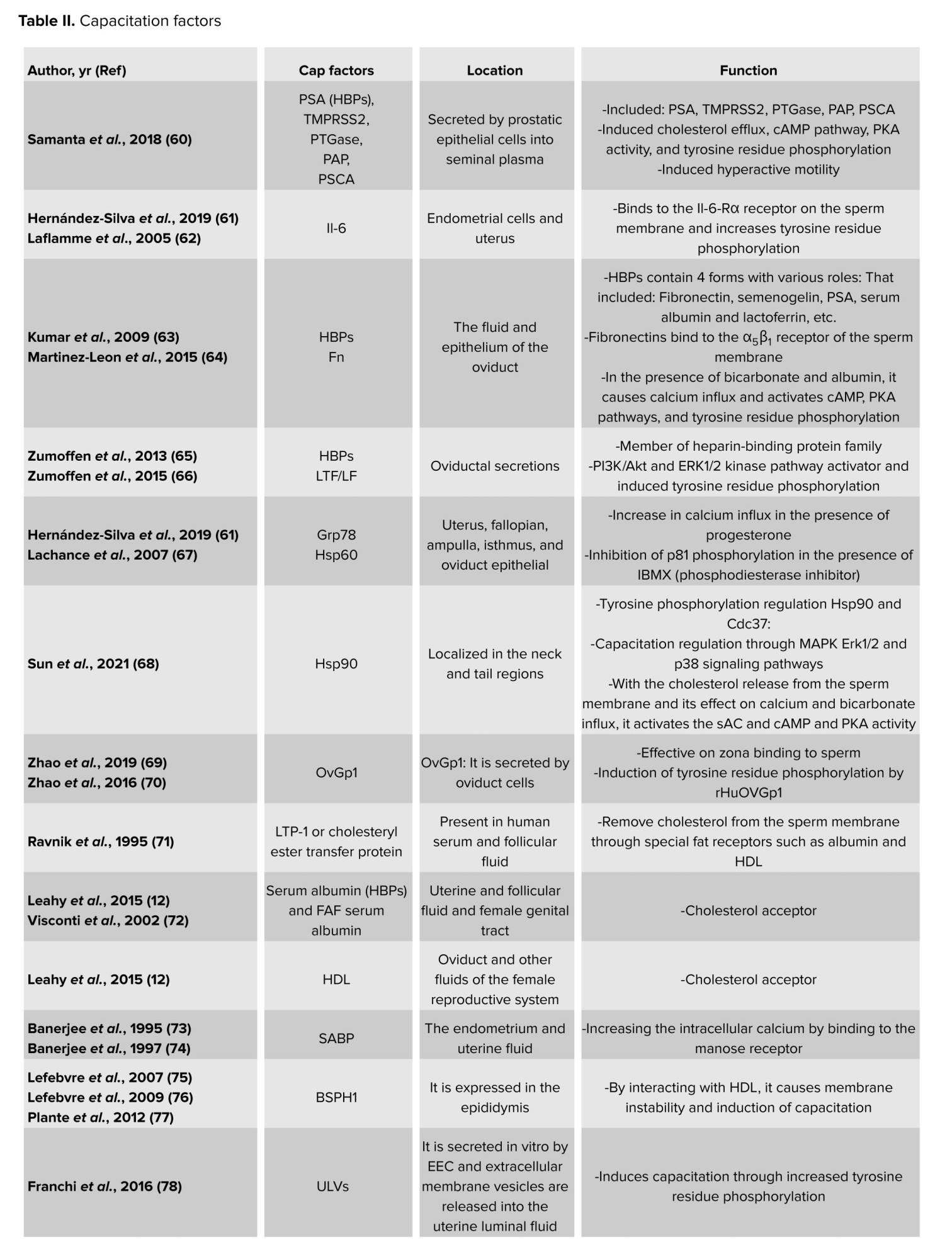

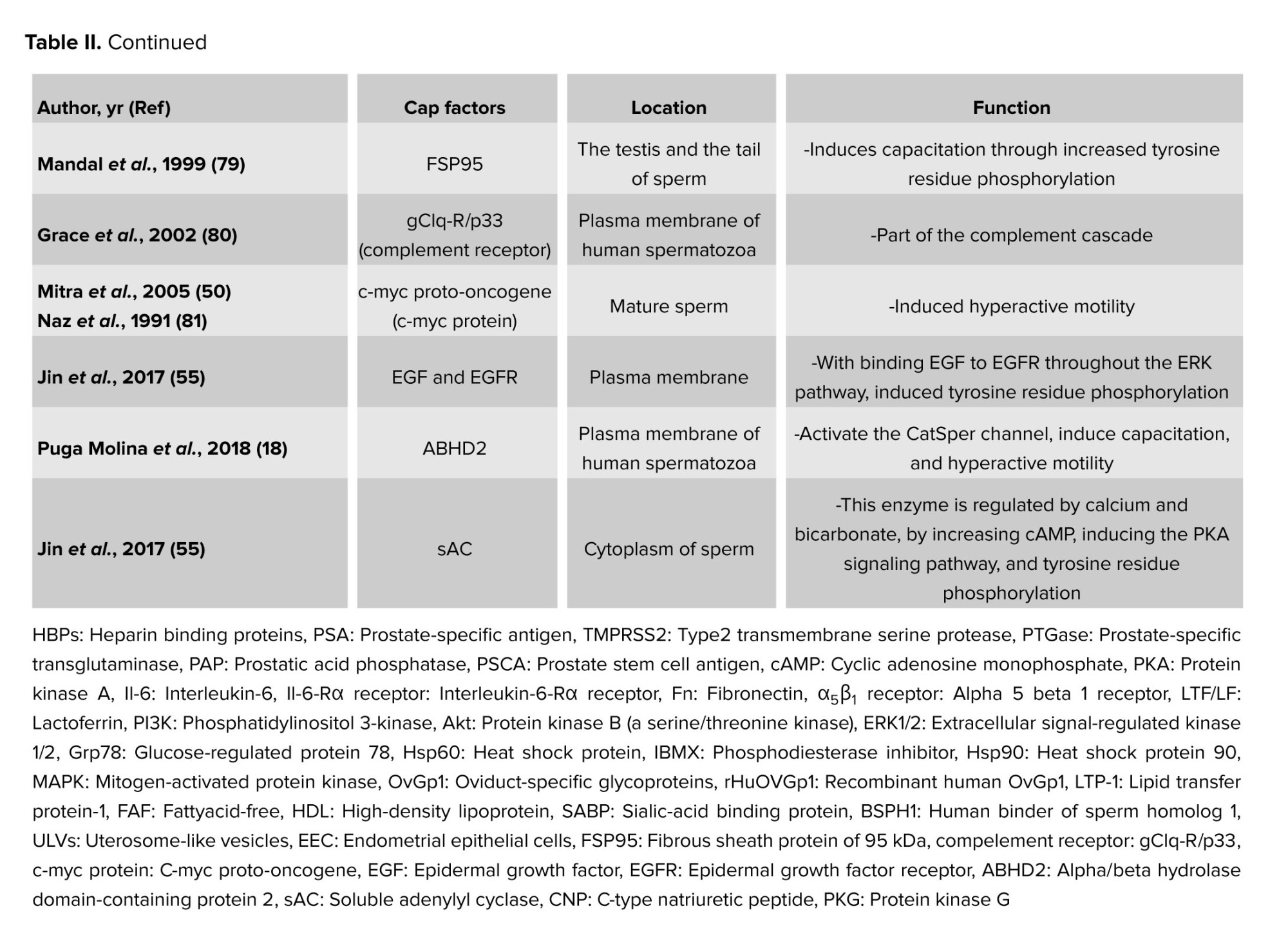

The first step for inducing capacitation is the extraction of sperm membrane-stabilizing elements in the cervical mucus. The last stages of sperm migration in the female reproductive system are the acrosome response and egg fertilization (51, 52). Decapacitation factors, as previously indicated, aid in stabilizing the cell membrane to prevent sperm from undergoing capacitation prematurely before reaching the female reproductive tract, thus protecting them from early capacitation processes (8-10). When sperm enter the female reproductive tract, the decapacitation factors are eliminated (53), and several molecular processes occur. These include the removal of cholesterol from the sperm plasma membrane, an increase in the membrane’s fluidity and permeability (54), the influx of Ca2+ into the sperm cell, the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in several proteins, the initiation of signaling cascade pathways that lead to capacitation, and the conversion of sperm motility to hyperactive motility (55). According to recent research, factors that cause capacitation or decapacitation may affect the processes involved in capacitation utilizing secretory routes or external membrane vesicles like prostasomes (56), which carry proteins, lipids, DNA, micro ribonucleic acid, and messenger ribonucleic acid (57-59). A selection of the key capacitation protein factors is displayed in table II. More protein families that could have several proteins engaged in the capacitation process are also included in this table.

6. Membrane channels and capacitation

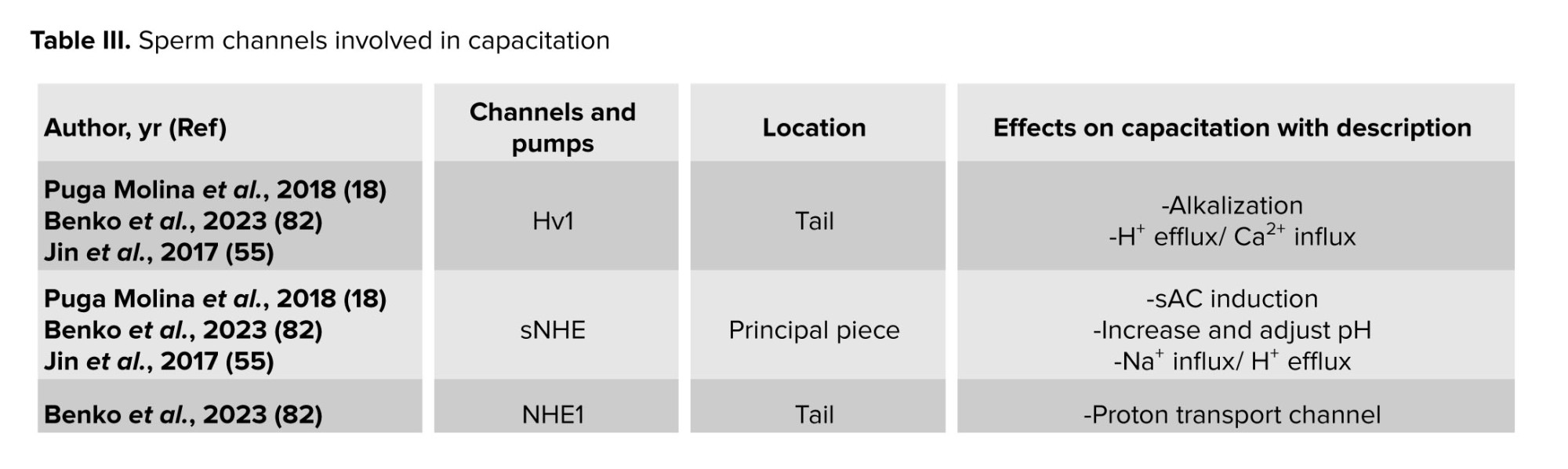

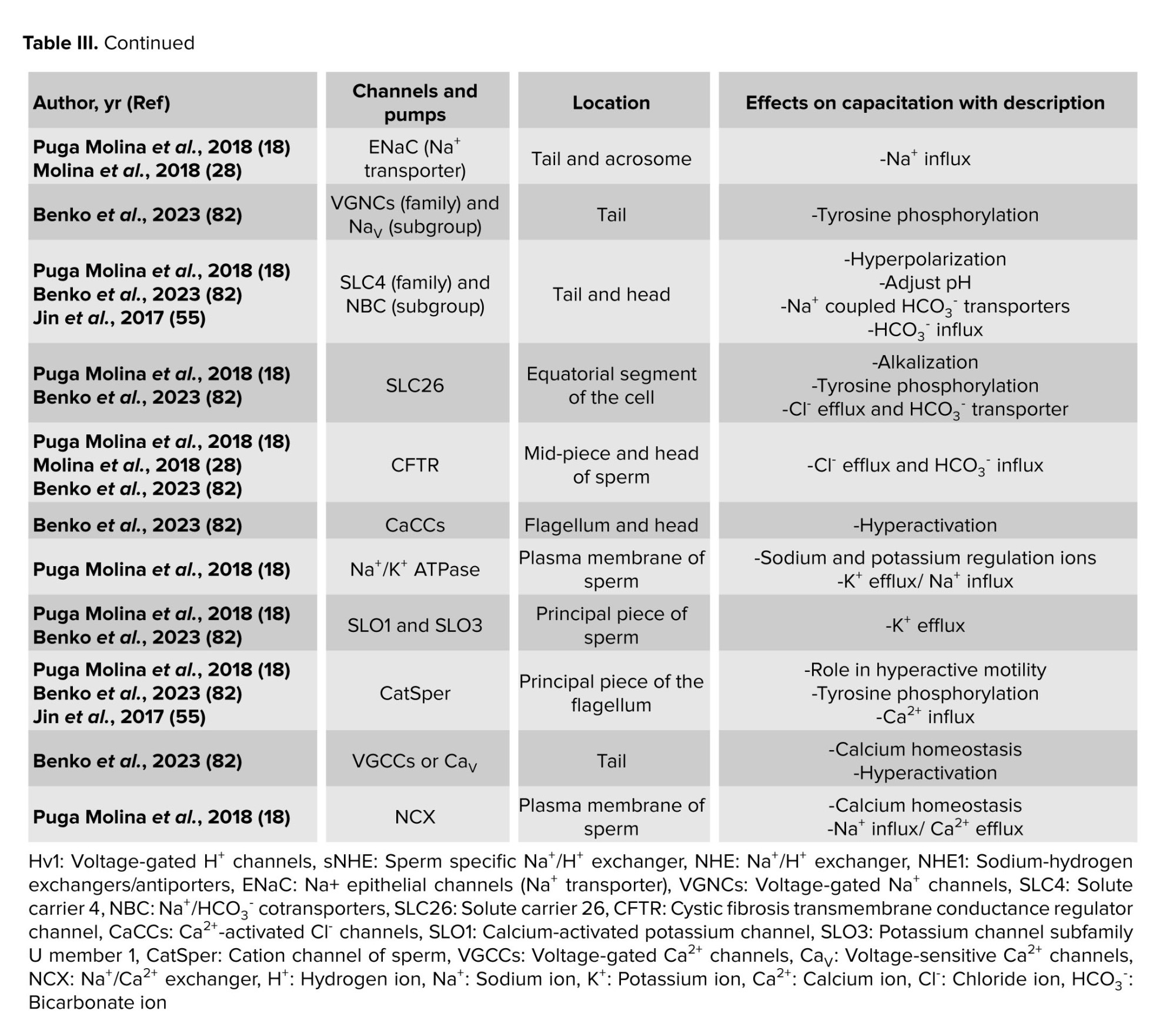

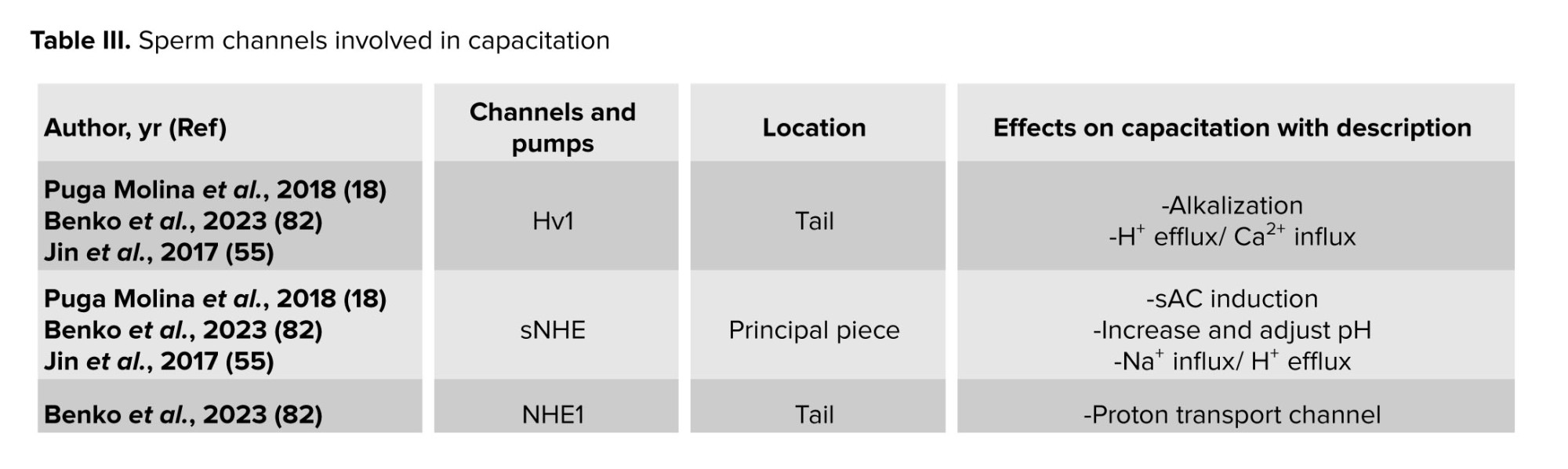

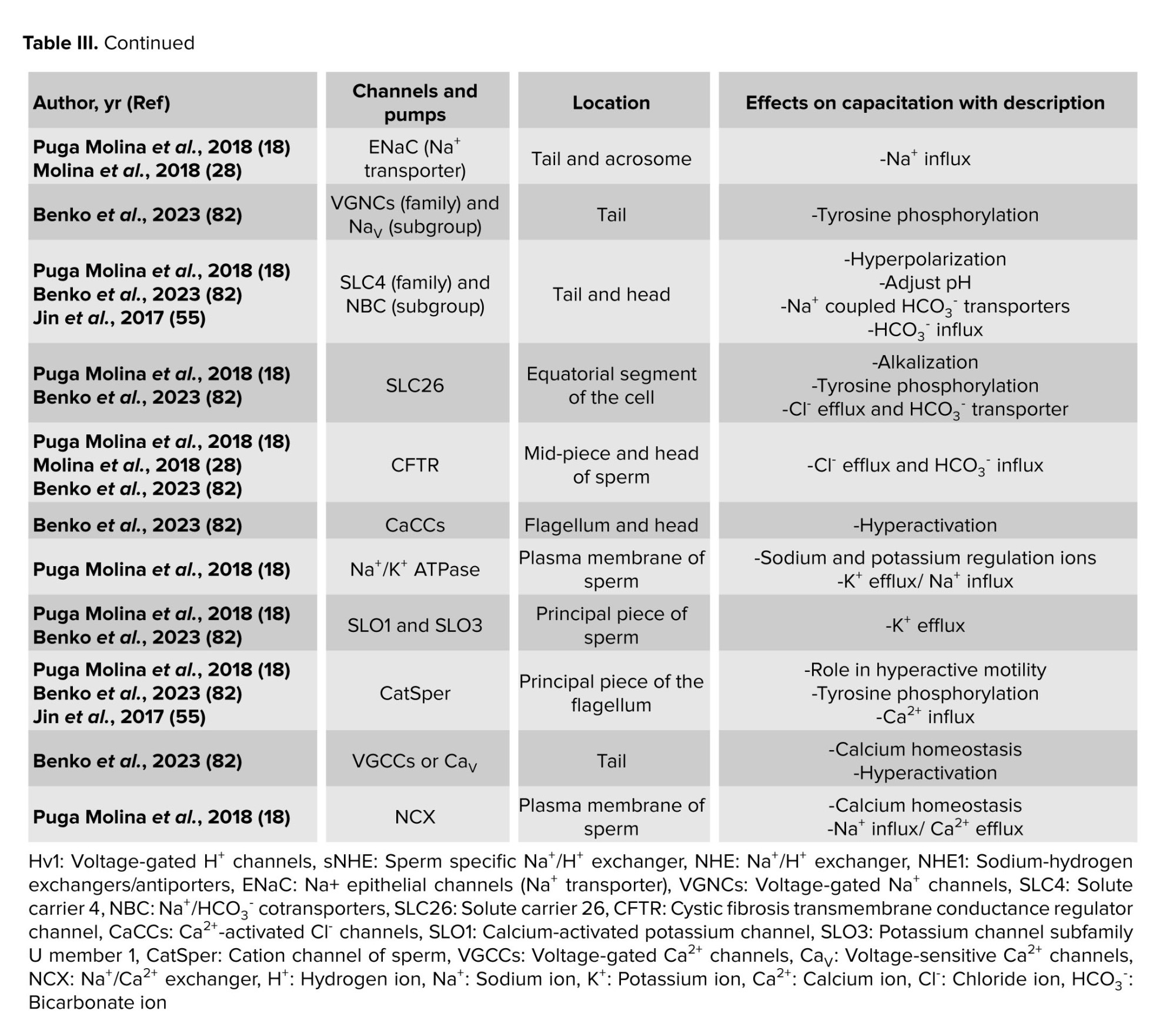

Certain ion channels in the sperm membrane, mostly made of proteins, aid in sperm capacitation. The behavior of these channels is dependent on the location and ionic changes of the surrounding environment. Consequently, capacitation is either caused by the activation or inactivation of these channels. The beginning of the capacitation cascades may be indicated by a change in the ions Ca2+, Na+, HCO3-, and H+. These channels may thus be referred to as both capacitation factors participating in the process and decapacitation factors that obstruct it (18). As a result, table III presents the individual sperm channels involved in determining the capacitation.

7. Conclusion

Capacitation is a crucial step in the journey of sperm toward fertilization, representing one of the final stages of sperm maturation. During this process, sperm undergo dramatic changes in their movement and membrane structure, preparing them to successfully penetrate and fertilize the egg. The timing and location of capacitation are tightly regulated, ensuring that sperm are ready at just the right moment and place. This delicate balance is maintained by a complex network of molecular signals, with various proteins and factors either promoting or inhibiting the process. In this review, we explored several key proteins that play a role in capacitation. Many of the factors that help capacitation are found in the fluid of the female fallopian tubes, while those that prevent it are mostly present in semen. The tables in this review highlight the different protein families involved. Interestingly, some proteins have dual roles, while their primary function may be unrelated to fertilization, they can still influence capacitation. For example, heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) helps capacitation, while semenogelin, which mainly prevents semen from liquefying, acts as a decapacitation factor. Other proteins, such as serum albumin, prostate-specific antigen, and lactoferrin, can both promote and inhibit capacitation depending on the context.

Looking ahead, a deeper understanding of these proteins and ion channels could transform how we approach male infertility and contraception. By uncovering the precise roles of capacitation-related molecules, researchers may develop new diagnostic tools and treatments that target these pathways directly. Advances in technologies like proteomics and single-cell analysis could reveal previously unknown regulators of sperm function, while improved imaging techniques may allow scientists to watch capacitation unfold in real time. In the clinic, this knowledge could lead to better culture media for assisted reproductive technologies, helping more couples achieve successful fertilization. Ultimately, unraveling the dual roles of capacitating and decapacitating proteins may pave the way for personalized fertility treatments and innovative approaches to reproductive health.

7.1. Strengths and limitations

Although this review offers a thorough summary of the state of the art regarding proteins and channels in human sperm capacitation, it is crucial to recognize its inherent limitations. First of all, a major limitation is the strong dependence on in vitro research, which is crucial for understanding mechanisms. The intricate physiological milieu of the female reproductive tract, which includes dynamic interactions with oviductal epithelia, follicular fluid, and hormonal changes, cannot be accurately replicated by these models. Therefore, it is still necessary to completely evaluate the in vivo significance of some postulated pathways (83).

Second, animal models provide a significant amount of the field’s evidence. As stated in our title and search criteria, we have attempted to concentrate our evaluation primarily on the “human path”, even though it is crucial for fundamental discoveries. However, because the molecular machinery of capacitation varies by species, it is frequently difficult to directly translate findings from model species to humans. This draws attention to a significant gap in the literature and a field that needs more targeted study on human sperm (84).

Lastly, the use of pharmaceutical inhibitors or antibodies is frequently necessary for the functional evaluation of numerous proteins and channels linked to capacitation. The precise function of some molecules may need to be confirmed using more focused genetic or molecular techniques, which are currently less practical in human sperm due to the possibility of off-target effects and partial pathway suppression with these tools. By pointing out these drawbacks, we hope to present a fair analysis and identify important topics for further research to further the subject (85).

The future of research on human sperm capacitation is represented by a number of intriguing directions that build upon the current knowledge and recognized limits. First off, there is great potential for using cutting-edge multiomics technologies on human sperm, such as lipidomics, phosphoproteomics, and single-cell proteomics. By exposing previously unknown protein targets, post-translational changes, and intricate signaling networks, these methods can offer an objective, systems-level perspective on the molecular cascades during capacitation (86, 87).

Second, more physiologically accurate in vitro models that more closely resemble the female reproductive system must be created immediately. This entails establishing co-culture systems with human oviductal cells and adding hormonal gradients and dynamic fluid flows. By enabling the study of sperm-oviduct interaction and the sequential exposure to various microenvironments, these models are crucial for bridging the gap between traditional in vitro results and the actual in vivo environment (88).

Moreover, pharmacological inhibition alone is insufficient for the functional confirmation of candidate proteins and channels. In order to selectively alter protein function without endangering sperm viability, the future will involve creating new molecular tools that are compatible with human sperm, such as molecular decoys, nanobodies, or sophisticated CRISPR-interference approaches. More accurate causal conclusions will be possible as a result (85, 89). Last but not least, putting this basic knowledge into practice is a top priority. Finding distinct protein signatures or channel activities linked to capacitation success may help develop new diagnostic tests for male infertility and therapeutic targets for its treatment; for example, certain channel agonists or inhibitors may be used to suppress or strategically enhance capacitation in vitro for assisted reproductive technologies, thereby increasing success rates (86, 89).

Author Contributions

N. Malverdi: Conceptualization, editing and writing. Sh. Kazemi: Conceptualization, editing and writing. N. Tavakoli: Writing. MR. Deemeh: Conceptualization and editing. M. Abedinzadeh: Editing. S. Vahidi: Editing. P. Salehi: Editing and supervision.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their special thanks to the Nobel Mega Laboratory of Isfahan, Iran for their cooperation. No artificial intelligence tool was not used in this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Full-Text: (19 Views)

1. Introduction

All in all, for fertilization, sperm must be alive and have appropriate changes in terms of membrane, morphology, and motility, and also their DNA should be healthy (1-3). After the production and maturation of sperm in the testes and epididymis, and during the sperm migration after ejaculation in the female genital tube, a variety of physiological events occur for prepared sperm that lead them to attach and penetrate the oocyte and fertilize it. One of the most important physiological changes in sperm is capacitation (4).

Capacitation includes a series of cellular and molecular events that assist in modifying the sperm membrane’s structure and shape, affect how well ionic channels work, and unfold certain receptors (5). Moreover, during capacitation, sperm motility alters in type, resulting in hyperactive motility patterns (6). For fertilization to be effective, capacitation in the female genital tube must occur at the appropriate times and locations. Capacitation typically begins in the uterus and becomes stronger in the fallopian tube and lasts until the sperm reaches the released egg (7).

However, certain components of the semen prevent sperm from prematurely capacitation before they ever get to the uterus. Due to these decapacitation factors found in semen, capacitation does not occur until the sperm are in seminal fluid. Furthermore, since the uterine and fallopian tubes contain components that promote capacitation, sperm entrance into the uterus is stimulated (8-10).

In this review, protein factors that either promote or inhibit capacitation, also referred to as “capacitation and decapacitation factors”, as well as their effects on capacitation signaling, will be discussed. This article concentrates on the human process assisting in identifying proteins and creating a proteome map.

2. Search methodology

2.1. Search strategy

To find pertinent research on the proteins and ion channels involved in human sperm capacitation, a thorough and organized literature search was carried out. Ensuring a reproducible and objective compilation of the most important studies in the field was the main objective. The majority of the research in this field was done using Google Scholar, Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus. Lastly, the human route was the subject of further research.

To cover the whole contemporary age of capacitation research, the search included works published from each database until 2024. Medical subject headings terms and keywords were combined.

The core search string was built around the following concepts:

All in all, for fertilization, sperm must be alive and have appropriate changes in terms of membrane, morphology, and motility, and also their DNA should be healthy (1-3). After the production and maturation of sperm in the testes and epididymis, and during the sperm migration after ejaculation in the female genital tube, a variety of physiological events occur for prepared sperm that lead them to attach and penetrate the oocyte and fertilize it. One of the most important physiological changes in sperm is capacitation (4).

Capacitation includes a series of cellular and molecular events that assist in modifying the sperm membrane’s structure and shape, affect how well ionic channels work, and unfold certain receptors (5). Moreover, during capacitation, sperm motility alters in type, resulting in hyperactive motility patterns (6). For fertilization to be effective, capacitation in the female genital tube must occur at the appropriate times and locations. Capacitation typically begins in the uterus and becomes stronger in the fallopian tube and lasts until the sperm reaches the released egg (7).

However, certain components of the semen prevent sperm from prematurely capacitation before they ever get to the uterus. Due to these decapacitation factors found in semen, capacitation does not occur until the sperm are in seminal fluid. Furthermore, since the uterine and fallopian tubes contain components that promote capacitation, sperm entrance into the uterus is stimulated (8-10).

In this review, protein factors that either promote or inhibit capacitation, also referred to as “capacitation and decapacitation factors”, as well as their effects on capacitation signaling, will be discussed. This article concentrates on the human process assisting in identifying proteins and creating a proteome map.

2. Search methodology

2.1. Search strategy

To find pertinent research on the proteins and ion channels involved in human sperm capacitation, a thorough and organized literature search was carried out. Ensuring a reproducible and objective compilation of the most important studies in the field was the main objective. The majority of the research in this field was done using Google Scholar, Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus. Lastly, the human route was the subject of further research.

To cover the whole contemporary age of capacitation research, the search included works published from each database until 2024. Medical subject headings terms and keywords were combined.

The core search string was built around the following concepts:

- Concept 1: sperm capacitation

- Concept 2: proteins/ion channels

- Concept 3: human

2.2. Data extraction

To identify research that specifically examined the function of particular proteins or channels in the physiological process of human sperm capacitation, the retrieved records were filtered by title and abstract. The eligibility of full-text publications of possibly pertinent research was then evaluated. To find any more relevant publications that might have been overlooked in the database search, the reference lists of important review articles and qualified primary research were searched manually.

3. Capacitation mechanism

One of the most significant changes occurs during capacitation when the cholesterol levels in the sperm membrane attenuate and drop (11). Many proteins serve as acceptors for cholesterol, allowing the substance to be transferred from the sperm membrane to the proteins themselves (12).

It is possible to think of these proteins as capacitation factors. When it is present in vivo, the lipid transfer protein I is a crucial cholesterol acceptor in the female reproductive system. Key proteins in this biological process include caveolin 1 and 2, flotillin 1 and 2, and several important gangliosides present in the membrane lipid rafts (13, 14). Interestingly, the albumin protein plays a crucial role as a cholesterol acceptor in both in vivo contexts, such as uterine and follicular fluids (15), and in vitro contexts, like culture media (12). Sperm capacitation is induced as a result of this disturbance of the cholesterol balance in the membrane, clustering of monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1), and aggregation of zona pellucida (ZP)-binding molecules (16, 17).

The concentration of electrolytes varies in the environments that sperm encounter during their migration into the oocyte. Variations in the amounts of intracellular and external electrolytes cause protein kinase activity to trigger the capacitation signaling pathway (18). As sperm approaches the egg, several electrolyte concentrations change, which surely affects the intracellular electrolyte concentration in the sperm. Furthermore, the specific channels in the sperm membrane that permit the passage of certain ions, like the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel (CFTR), Na+/HCO3- cotransporters (NBC), sperm specific Na+/H+ exchanger, and others, help regulate fluctuations in the concentrations of electrolytes (19). One important factor influencing the onset of capacitation signaling was elevated bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) concentrations. HCO3- is entered in the sperm by stimulating certain CFTR channels, particularly in the fallopian tube (20). Adenylate cyclase 10 is a solute found in the cytoplasm of sperm that is triggered instantly by an increase in HCO3- (21).

Intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) increases as a result of this mechanism (22). Proteins implicated in the capacitation route have their tyrosine residues phosphorylated by cAMP, which activates intracellular protein kinases, particularly protein kinase A (PKA) (23). PKA is more responsible for tyrosine residue phosphorylation of proteins involved in capacitation (24). Another electrolyte signaling pathway, induced capacitation, involves variations in hydrogen ion (H+) concentration or pH. Certain channels and the extracellular H+ concentration both affect pH control. Sperm pH regulation is mostly dependent on the bicarbonate exchange channels and the Na+/H+ exchanger, and also pH fluctuations depend on Hv families such as voltage-gated H+ channels (Hv1) (Figure 1) (25). The CFTR channel is one of the main HCO3- channels in sperm (26).

The CFTR interaction with solute carrier 26 channels (27, 28). One sign of cystic fibrosis, which is brought on by genetic anomalies in these channels, is the immobility of the sperm (29). Potassium ion (K+) channels, commonly referred to as calcium-activated potassium channel and 3 (K+ channels 1 and 3), are responsible for both causing and controlling pH changes (30). Sodium/potassium ATP pumps are also significant in this regard (18). Calcium is another essential electrolyte that helps with the initiation and progression of capacitation. Calcium can bind and strengthen binders found in several enzymes involved in the capacitation process (31) that lead to controls of the levels of key enzymes such as phosphatase, phosphodiesterase, adenylate cyclase, and protein kinases based on capacitation by binding calcium ion (Ca2+) to calmodulin receptors or in other ways (32).

Specific channels in sperm are responsible for transporting Ca2+, which precisely control their concentration. There are 2 main kinds of channels: the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase family, which releases calcium when ATP energy is present and stores it in cellular reservoirs (33); and the cation channels of sperm (CatSper) family, a significant family of voltage-dependent calcium channels that is crucial for supplying Ca2+and modifying the type of motility in sperm (34, 35). Particularly, CatSper 1, 2, and 4 are crucial in causing sperm capacitation by hyperactive motility (36). Sperm that do not have these channel genes are unable to produce agitated motions (18, 19). Figure 1 is a popular representation of the processes involved in human sperm capacitation. The remarks provided a summary of the molecular process of capacitation, with each pathway being covered in considerable depth.

4. Decapacitation factors

Although female vaginal tubes often include capacitation factors, there are occasionally outliers; seminal fluid generally contains decapacitation factors (9, 10). Sperm should not be kept capacitated in the seminal fluid for an extended period, as this might impair their physiological capacity to fertilize in a timely and suitable way (37). Semen includes a variety of proteins and non-protein components that help postpone early capacitation in addition to providing sperm with a nutritional environment that is conducive to their survival. Most of these substances preserve and stop the sperm membrane’s structure from altering in semen plasma. As majority of these chemicals are secreted by the accessory glands.

Nevertheless, some of these variables may also be involved in capacitation inhibition during sperm maturation because they have also been observed in the epididymis (8-10). A few of the crucial decapacitation protein factors are displayed in table I. The protein families that might have multiple proteins engaged in the decapacitation process are also included in this table.

5. Capacitation factors

The first step for inducing capacitation is the extraction of sperm membrane-stabilizing elements in the cervical mucus. The last stages of sperm migration in the female reproductive system are the acrosome response and egg fertilization (51, 52). Decapacitation factors, as previously indicated, aid in stabilizing the cell membrane to prevent sperm from undergoing capacitation prematurely before reaching the female reproductive tract, thus protecting them from early capacitation processes (8-10). When sperm enter the female reproductive tract, the decapacitation factors are eliminated (53), and several molecular processes occur. These include the removal of cholesterol from the sperm plasma membrane, an increase in the membrane’s fluidity and permeability (54), the influx of Ca2+ into the sperm cell, the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in several proteins, the initiation of signaling cascade pathways that lead to capacitation, and the conversion of sperm motility to hyperactive motility (55). According to recent research, factors that cause capacitation or decapacitation may affect the processes involved in capacitation utilizing secretory routes or external membrane vesicles like prostasomes (56), which carry proteins, lipids, DNA, micro ribonucleic acid, and messenger ribonucleic acid (57-59). A selection of the key capacitation protein factors is displayed in table II. More protein families that could have several proteins engaged in the capacitation process are also included in this table.

6. Membrane channels and capacitation

Certain ion channels in the sperm membrane, mostly made of proteins, aid in sperm capacitation. The behavior of these channels is dependent on the location and ionic changes of the surrounding environment. Consequently, capacitation is either caused by the activation or inactivation of these channels. The beginning of the capacitation cascades may be indicated by a change in the ions Ca2+, Na+, HCO3-, and H+. These channels may thus be referred to as both capacitation factors participating in the process and decapacitation factors that obstruct it (18). As a result, table III presents the individual sperm channels involved in determining the capacitation.

7. Conclusion

Capacitation is a crucial step in the journey of sperm toward fertilization, representing one of the final stages of sperm maturation. During this process, sperm undergo dramatic changes in their movement and membrane structure, preparing them to successfully penetrate and fertilize the egg. The timing and location of capacitation are tightly regulated, ensuring that sperm are ready at just the right moment and place. This delicate balance is maintained by a complex network of molecular signals, with various proteins and factors either promoting or inhibiting the process. In this review, we explored several key proteins that play a role in capacitation. Many of the factors that help capacitation are found in the fluid of the female fallopian tubes, while those that prevent it are mostly present in semen. The tables in this review highlight the different protein families involved. Interestingly, some proteins have dual roles, while their primary function may be unrelated to fertilization, they can still influence capacitation. For example, heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) helps capacitation, while semenogelin, which mainly prevents semen from liquefying, acts as a decapacitation factor. Other proteins, such as serum albumin, prostate-specific antigen, and lactoferrin, can both promote and inhibit capacitation depending on the context.

Looking ahead, a deeper understanding of these proteins and ion channels could transform how we approach male infertility and contraception. By uncovering the precise roles of capacitation-related molecules, researchers may develop new diagnostic tools and treatments that target these pathways directly. Advances in technologies like proteomics and single-cell analysis could reveal previously unknown regulators of sperm function, while improved imaging techniques may allow scientists to watch capacitation unfold in real time. In the clinic, this knowledge could lead to better culture media for assisted reproductive technologies, helping more couples achieve successful fertilization. Ultimately, unraveling the dual roles of capacitating and decapacitating proteins may pave the way for personalized fertility treatments and innovative approaches to reproductive health.

7.1. Strengths and limitations

Although this review offers a thorough summary of the state of the art regarding proteins and channels in human sperm capacitation, it is crucial to recognize its inherent limitations. First of all, a major limitation is the strong dependence on in vitro research, which is crucial for understanding mechanisms. The intricate physiological milieu of the female reproductive tract, which includes dynamic interactions with oviductal epithelia, follicular fluid, and hormonal changes, cannot be accurately replicated by these models. Therefore, it is still necessary to completely evaluate the in vivo significance of some postulated pathways (83).

Second, animal models provide a significant amount of the field’s evidence. As stated in our title and search criteria, we have attempted to concentrate our evaluation primarily on the “human path”, even though it is crucial for fundamental discoveries. However, because the molecular machinery of capacitation varies by species, it is frequently difficult to directly translate findings from model species to humans. This draws attention to a significant gap in the literature and a field that needs more targeted study on human sperm (84).

Lastly, the use of pharmaceutical inhibitors or antibodies is frequently necessary for the functional evaluation of numerous proteins and channels linked to capacitation. The precise function of some molecules may need to be confirmed using more focused genetic or molecular techniques, which are currently less practical in human sperm due to the possibility of off-target effects and partial pathway suppression with these tools. By pointing out these drawbacks, we hope to present a fair analysis and identify important topics for further research to further the subject (85).

The future of research on human sperm capacitation is represented by a number of intriguing directions that build upon the current knowledge and recognized limits. First off, there is great potential for using cutting-edge multiomics technologies on human sperm, such as lipidomics, phosphoproteomics, and single-cell proteomics. By exposing previously unknown protein targets, post-translational changes, and intricate signaling networks, these methods can offer an objective, systems-level perspective on the molecular cascades during capacitation (86, 87).

Second, more physiologically accurate in vitro models that more closely resemble the female reproductive system must be created immediately. This entails establishing co-culture systems with human oviductal cells and adding hormonal gradients and dynamic fluid flows. By enabling the study of sperm-oviduct interaction and the sequential exposure to various microenvironments, these models are crucial for bridging the gap between traditional in vitro results and the actual in vivo environment (88).

Moreover, pharmacological inhibition alone is insufficient for the functional confirmation of candidate proteins and channels. In order to selectively alter protein function without endangering sperm viability, the future will involve creating new molecular tools that are compatible with human sperm, such as molecular decoys, nanobodies, or sophisticated CRISPR-interference approaches. More accurate causal conclusions will be possible as a result (85, 89). Last but not least, putting this basic knowledge into practice is a top priority. Finding distinct protein signatures or channel activities linked to capacitation success may help develop new diagnostic tests for male infertility and therapeutic targets for its treatment; for example, certain channel agonists or inhibitors may be used to suppress or strategically enhance capacitation in vitro for assisted reproductive technologies, thereby increasing success rates (86, 89).

Author Contributions

N. Malverdi: Conceptualization, editing and writing. Sh. Kazemi: Conceptualization, editing and writing. N. Tavakoli: Writing. MR. Deemeh: Conceptualization and editing. M. Abedinzadeh: Editing. S. Vahidi: Editing. P. Salehi: Editing and supervision.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their special thanks to the Nobel Mega Laboratory of Isfahan, Iran for their cooperation. No artificial intelligence tool was not used in this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Biology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |