Thu, Feb 19, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 23, Issue 11 (November 2025)

IJRM 2025, 23(11): 911-926 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.UMA.REC.1403.031

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Farhadi A, Zolfagharpour F, Abdolmaleki A, Asadi A, Zabihi A. Protective effects of selenium nanoparticles against X-ray-induced testicular damage in rats: An integrated experimental and Monte Carlo simulation study. IJRM 2025; 23 (11) :911-926

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3595-en.html

URL: http://ijrm.ir/article-1-3595-en.html

1- Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,Zolfagharpour@uma.ac.ir

3- Department of Biophysics, Faculty of Advanced Technologies, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Namin, Ardabil, Iran.

4- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

5- AstroCeNT, Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland.

2- Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biophysics, Faculty of Advanced Technologies, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Namin, Ardabil, Iran.

4- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

5- AstroCeNT, Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland.

Full-Text [PDF 3644 kb]

(272 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (182 Views)

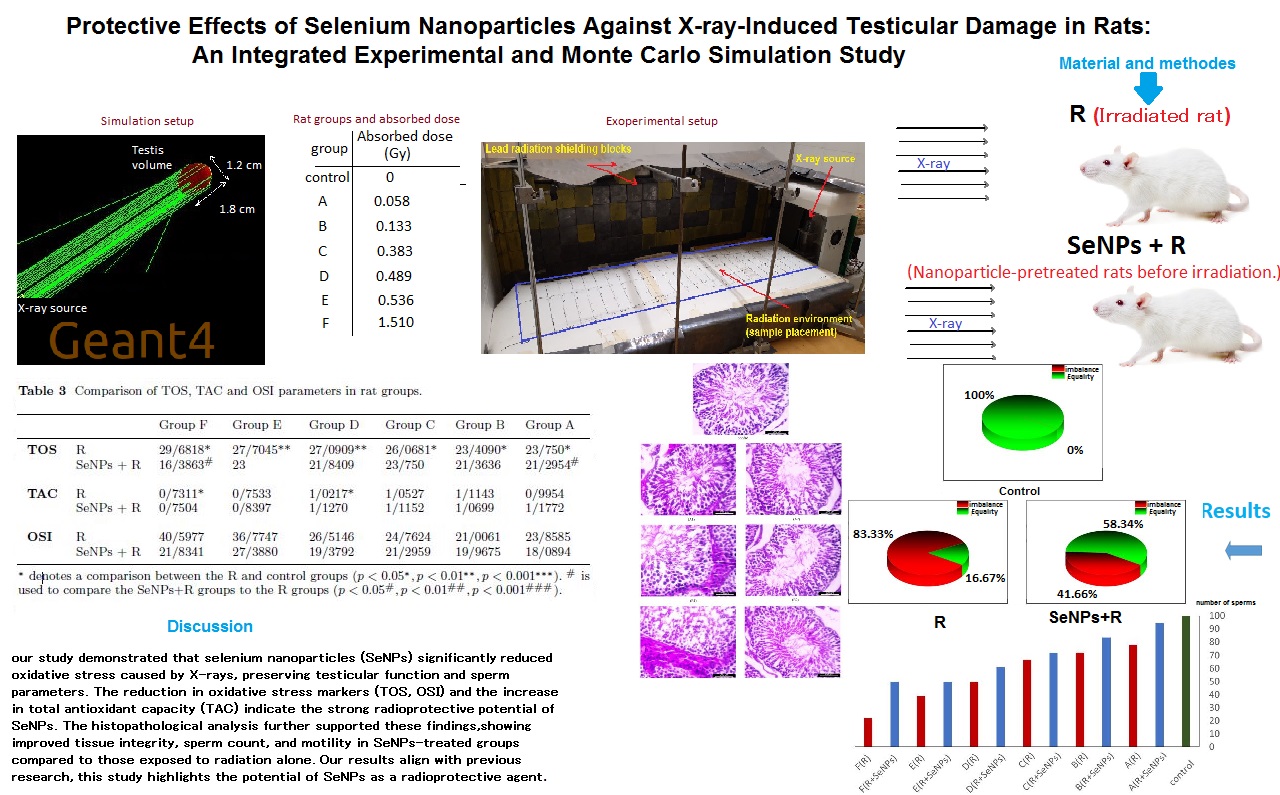

2.1.3. Radiation dose assessment

2.2.2. Average electron fluence calculation

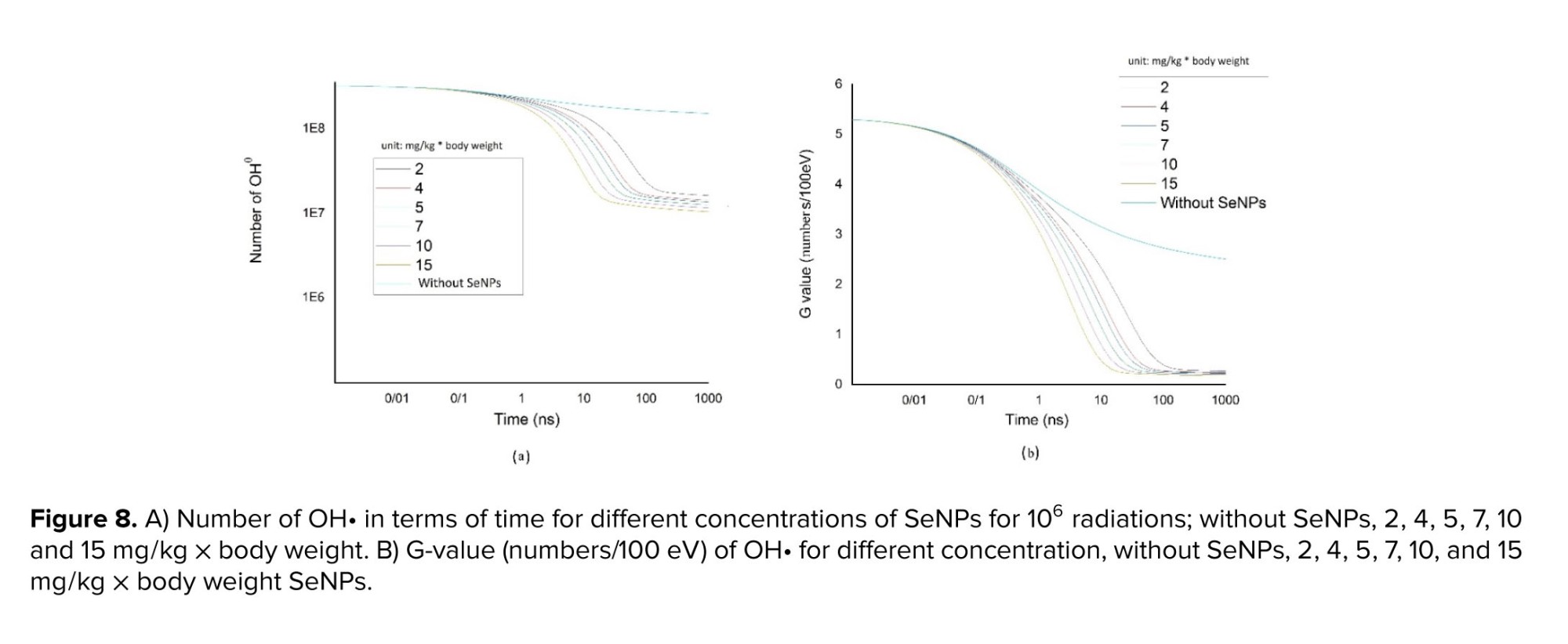

3.7. G-value result

Full-Text: (21 Views)

1. Introduction

Ionizing radiation was widely used in medicine, industry, and scientific research (1). However, its biological side effects, especially on the male reproductive system, were a growing concern. The testes were highly radiosensitive due to the abundance of water and the rapid division of germ cells, making them particularly susceptible to oxidative damage (2).

Radiation-induced testicular damage resulted primarily from the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydroxyl radicals (OH•), which caused lipid peroxidation, DNA fragmentation, and apoptosis of spermatogenic cells. These effects ultimately impaired spermatogenesis and reduced male fertility (2).

Previous studies demonstrated that antioxidants mitigated oxidative stress, a key factor in male infertility, by neutralizing free radicals (3, 4). Among these, selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) emerged as promising candidates due to their high bioavailability, low toxicity, and regulatory effects on redox signaling pathways (5). SeNPs were shown to protect testicular tissue by downregulating pro-apoptotic genes such as caspase-3 and upregulating anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2, thereby maintaining normal testicular function and morphology (6).

In various animal models, SeNPs improved sperm count, motility, and morphology, and reduced testicular damage caused by agents such as doxorubicin and monosodium glutamate (7). Furthermore, investigations demonstrated radioprotective effects of SeNPs in rats exposed to X-rays (8). However, few studies investigated their effects against X-ray-induced testicular injury using a combined approach of biological assessment and simulation-based modeling. In particular, the molecular mechanisms by which SeNPs interact with OH• during radiation-induced water radiolysis remain poorly understood. Rats were selected for this study due to their physiological and anatomical similarities to humans in testicular structure, sperm biology, and response to oxidative stress. Their use was well established in studies on radiation-induced testicular damage and male fertility (9). This study aimed to evaluate the radioprotective effects of SeNPs against X-ray-induced testicular damage in rats through a combination of biological experiments and Monte Carlo simulation using Geant4/Geant4-DNA, a well-established toolkit in radiation biology (10-12). Biological assessments included sperm analysis, antioxidant measurements, and histopathology. To complement these findings, Geant4-DNA simulations were used to model hydroxyl radical generation and scavenging by SeNPs during the chemical phase of radiation interaction. This integrated approach provided a novel and more comprehensive understanding of SeNPs' protective role at both the tissue and molecular levels in radiation-induced testicular injury.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental step

This research was designed as a integrated and Monte Carlo simulation experimental study conducted to evaluate the protective effects of SeNPs against X-ray-induced testicular damage in rats. All experimental protocols, radiation exposures, and analyses were performed under controlled laboratory conditions to ensure reproducibility.

The study was carried out at the Radiation Physics Laboratory and the Biology Laboratory of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (Ardabil, Iran) between June and September 2024.

To evaluate the protective potential of SeNPs against X-ray-induced damage in rat testicular tissue, administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg, and their antioxidant properties were assessed in a laboratory setting. The SeNP dose of 5 mg/kg was chosen based on established literature demonstrating both radioprotective efficacy and safety in rodent models (8, 13). The evaluation included biological parameters such as total antioxidant capacity (TAC), total oxidant status (TOS), oxidative stress index (OSI), body and testicular weight changes, histological analysis, and sperm quality assessment after radiation.

2.1.1. Animals

A total of 42 male Wister rats (8-10 wk, 200-250 gr) were used in this experimental study. Animals were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Unit of the Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran). They were housed in plexiglas cages in groups of 6, maintained at 22 ± 2°C with a 12-hr light/dark cycle, and given unrestricted access to standard rodent chow and water. At the conclusion of the radiation period, all animals were euthanized humanely using CO₂ inhalation, and their remains were incinerated according to biosafety protocols.

2.1.2. Sample size

Ionizing radiation was widely used in medicine, industry, and scientific research (1). However, its biological side effects, especially on the male reproductive system, were a growing concern. The testes were highly radiosensitive due to the abundance of water and the rapid division of germ cells, making them particularly susceptible to oxidative damage (2).

Radiation-induced testicular damage resulted primarily from the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydroxyl radicals (OH•), which caused lipid peroxidation, DNA fragmentation, and apoptosis of spermatogenic cells. These effects ultimately impaired spermatogenesis and reduced male fertility (2).

Previous studies demonstrated that antioxidants mitigated oxidative stress, a key factor in male infertility, by neutralizing free radicals (3, 4). Among these, selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) emerged as promising candidates due to their high bioavailability, low toxicity, and regulatory effects on redox signaling pathways (5). SeNPs were shown to protect testicular tissue by downregulating pro-apoptotic genes such as caspase-3 and upregulating anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2, thereby maintaining normal testicular function and morphology (6).

In various animal models, SeNPs improved sperm count, motility, and morphology, and reduced testicular damage caused by agents such as doxorubicin and monosodium glutamate (7). Furthermore, investigations demonstrated radioprotective effects of SeNPs in rats exposed to X-rays (8). However, few studies investigated their effects against X-ray-induced testicular injury using a combined approach of biological assessment and simulation-based modeling. In particular, the molecular mechanisms by which SeNPs interact with OH• during radiation-induced water radiolysis remain poorly understood. Rats were selected for this study due to their physiological and anatomical similarities to humans in testicular structure, sperm biology, and response to oxidative stress. Their use was well established in studies on radiation-induced testicular damage and male fertility (9). This study aimed to evaluate the radioprotective effects of SeNPs against X-ray-induced testicular damage in rats through a combination of biological experiments and Monte Carlo simulation using Geant4/Geant4-DNA, a well-established toolkit in radiation biology (10-12). Biological assessments included sperm analysis, antioxidant measurements, and histopathology. To complement these findings, Geant4-DNA simulations were used to model hydroxyl radical generation and scavenging by SeNPs during the chemical phase of radiation interaction. This integrated approach provided a novel and more comprehensive understanding of SeNPs' protective role at both the tissue and molecular levels in radiation-induced testicular injury.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental step

This research was designed as a integrated and Monte Carlo simulation experimental study conducted to evaluate the protective effects of SeNPs against X-ray-induced testicular damage in rats. All experimental protocols, radiation exposures, and analyses were performed under controlled laboratory conditions to ensure reproducibility.

The study was carried out at the Radiation Physics Laboratory and the Biology Laboratory of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (Ardabil, Iran) between June and September 2024.

To evaluate the protective potential of SeNPs against X-ray-induced damage in rat testicular tissue, administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg, and their antioxidant properties were assessed in a laboratory setting. The SeNP dose of 5 mg/kg was chosen based on established literature demonstrating both radioprotective efficacy and safety in rodent models (8, 13). The evaluation included biological parameters such as total antioxidant capacity (TAC), total oxidant status (TOS), oxidative stress index (OSI), body and testicular weight changes, histological analysis, and sperm quality assessment after radiation.

2.1.1. Animals

A total of 42 male Wister rats (8-10 wk, 200-250 gr) were used in this experimental study. Animals were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Unit of the Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran). They were housed in plexiglas cages in groups of 6, maintained at 22 ± 2°C with a 12-hr light/dark cycle, and given unrestricted access to standard rodent chow and water. At the conclusion of the radiation period, all animals were euthanized humanely using CO₂ inhalation, and their remains were incinerated according to biosafety protocols.

2.1.2. Sample size

The sample size (n = 6/group) was determined based on previous studies that evaluated radiation-induced testicular damage and the protective effects of SeNPs in rodents (8, 14, 15). A total of 42 male rats were randomly divided into 7 groups. This design was intended to provide sufficient power to detect biologically relevant differences in sperm quality, antioxidant markers, and histological outcomes, in line with ethical standards for animal research. The group sizes were consistent with previous studies and were expected to provide sufficient power (~80%) at α = 0.05 to detect moderate-to-strong biological effects.

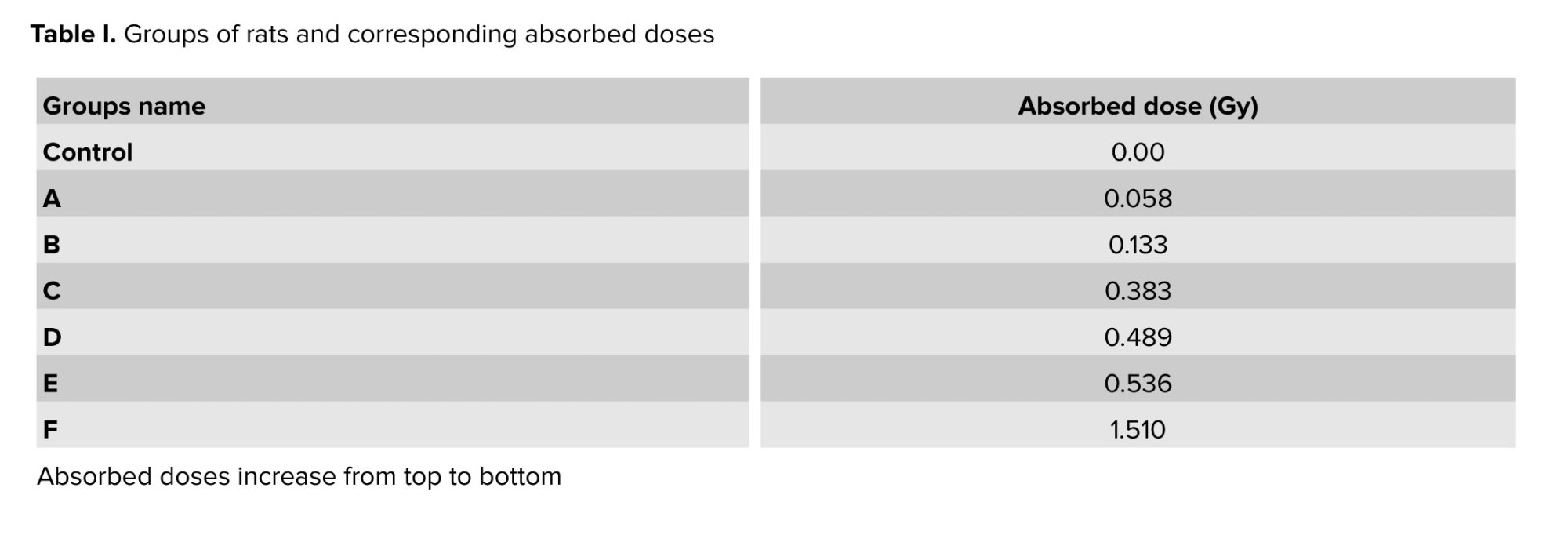

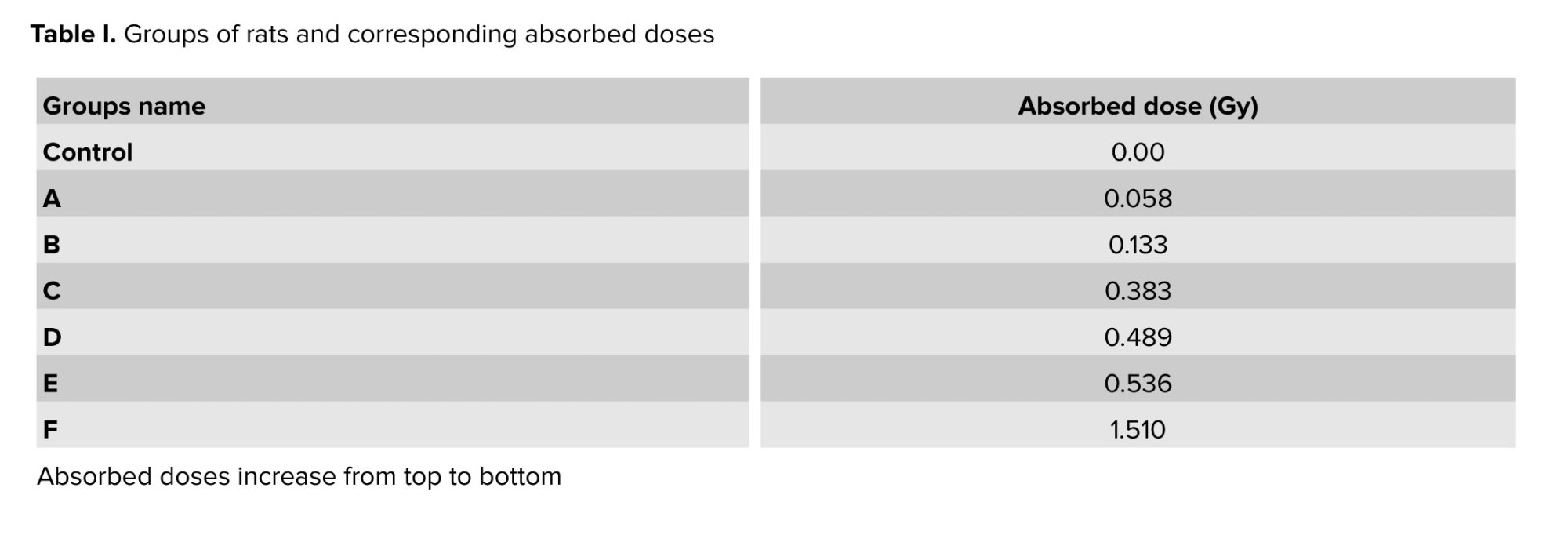

2.1.3. Radiation dose assessment

The irradiation setup is shown in figure 1. X-ray exposure was conducted using a Leybold (Germany) X-ray source, operating at 35 kilovolts (kV) and 0.1 milliamperes. The cages were positioned at varying distances from the source to achieve different dose levels. Dosimetry measurements were performed using a GRAETZ radiation dosimeter (Germany), which employs an energy-compensated Geiger-Müller counting tube for detection. The dosimeter was calibrated prior to measurements to ensure accuracy, and uncertainties were accounted for in accordance with standard dosimetry protocols.

The experimental setup included a cage divided into 9 sections to improve measurement accuracy, and the absorbed dose was recorded separately in each section over 1 hr. Since the rats moved freely within the cage, the statistical mean of these measurements was used as the representative absorbed dose. This approach accounts for the spatial distribution of radiation within the cage and the random movement of the rats, ensuring a statistically reliable estimation of their radiation exposure. The final absorbed dose was then integrated over the total exposure duration of 76 hr, yielding the total absorbed dose, as presented in table I.

2.1.4. Sample irradiation

The experimental setup included a cage divided into 9 sections to improve measurement accuracy, and the absorbed dose was recorded separately in each section over 1 hr. Since the rats moved freely within the cage, the statistical mean of these measurements was used as the representative absorbed dose. This approach accounts for the spatial distribution of radiation within the cage and the random movement of the rats, ensuring a statistically reliable estimation of their radiation exposure. The final absorbed dose was then integrated over the total exposure duration of 76 hr, yielding the total absorbed dose, as presented in table I.

2.1.4. Sample irradiation

7 groups of rats (n = 42) were randomly assigned, including a healthy control group that received no radiation or SeNPs. The remaining 6 groups, each consisting of 2 cages with 3 rats per cage, were exposed to X-ray irradiation for 76 hr, receiving absorbed doses ranging from 0.058-1.510 Gy (Table I). In each group, one cage received SeNPs before irradiation via intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight. The SeNPs-treated rats were identified by marking their tails.

The selected dose range (≈0.06-1.5 Gy) was chosen to induce measurable testicular injury without causing lethality. Previous radiobiological studies indicated that exposures within this interval reliably induced oxidative stress and disrupt spermatogenesis in rodents, while remaining below thresholds associated with systemic toxicity (16). This study, therefore, focused on relatively low absorbed doses, with higher-dose effects reserved for subsequent investigations.

To ensure identical irradiation conditions, both cages within a group were exposed simultaneously at the same distance from the radiation source to receive an equal radiation dose. The groups were irradiated separately over 76 hr period. To mitigate potential interference from water radiolysis, the irradiation process was paused twice daily for 1 hr, during which fresh water was provided to the animals. Given the maximum energy output of 35 kilo-electron volts (keV) from the X-ray apparatus, radiation protection measures were implemented. The apparatus was enclosed with 7-cm-thick lead bricks, while the upper and lower surfaces were covered with 2-mm-thick lead sheets (Figure 1).

2.1.5. Data collection and analysis

The selected dose range (≈0.06-1.5 Gy) was chosen to induce measurable testicular injury without causing lethality. Previous radiobiological studies indicated that exposures within this interval reliably induced oxidative stress and disrupt spermatogenesis in rodents, while remaining below thresholds associated with systemic toxicity (16). This study, therefore, focused on relatively low absorbed doses, with higher-dose effects reserved for subsequent investigations.

To ensure identical irradiation conditions, both cages within a group were exposed simultaneously at the same distance from the radiation source to receive an equal radiation dose. The groups were irradiated separately over 76 hr period. To mitigate potential interference from water radiolysis, the irradiation process was paused twice daily for 1 hr, during which fresh water was provided to the animals. Given the maximum energy output of 35 kilo-electron volts (keV) from the X-ray apparatus, radiation protection measures were implemented. The apparatus was enclosed with 7-cm-thick lead bricks, while the upper and lower surfaces were covered with 2-mm-thick lead sheets (Figure 1).

2.1.5. Data collection and analysis

2.1.5.1. TAC value

TAC of testicular tissue was assessed using a commercial assay kit provided by Kiazist Life Sciences Co. (Iran), following Erel’s protocol (17). The commercial assay is based on the reduction of a colored radical cation, where the decrease in absorbance at a specific wavelength, measured via spectrophotometry, reflects the antioxidant capacity of the sample. 24 hr after radiation exposure, testicular tissues were excised and mechanically homogenized in an appropriate buffer. The observed decrease in color intensity correlated with the concentration of antioxidant compounds. TAC levels were quantified and reported as micromolar Trolox equivalents per milligram of tissue protein (µmol Trolox Eq/mg protein).

2.1.5.2. TOS value

TOS in testicular tissue was quantified using a commercial assay kit from Kiazist Life Sciences (Iran), based on the protocol originally described by Erel (18). This method involves the oxidation of ferrous ions to ferric ions in the presence of oxidizing agents, followed by quantification with xylenol orange. TOS values were calculated as micromolar hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) equivalents per milligram of tissue protein, after calibration against a H₂O₂ standard.

2.1.5.3. OSI value

OSI was calculated by dividing the TOS value by TAC value and multiplying by 100 to express the result as a percentage. This index quantitatively assessed oxidative stress intensity, reflecting the balance between oxidant and antioxidant systems within the biological sample.

2.1.5.4. Histological evaluation

Histological evaluation of testicular tissue was performed using standard staining techniques, primarily hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (14). H&E staining is widely accepted as the standard method for the microscopic examination of fixed, processed, embedded, and sectioned tissues. Additionally, Masson’s trichrome stain was utilized for histological evaluation. Briefly, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-µm-thick slices using a microtome. These sections were subsequently deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained using Masson’s trichrome staining according to established protocols. After staining, the prepared slides were analyzed by light microscopy. In H&E-stained tissues, nucleic acids typically appear dark blue, while proteins exhibit red, pink, or orange shades.

2.1.5.5. Sperm parameters evaluation

Sperm analysis was performed in accordance with the World Health Organiation Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (19), with adaptations for rats. Following dissection, the cauda epididymis was placed in HEPES-buffered DMEM to allow spermatozoa to disperse. Sperm concentration was determined using a hemocytometer, with results expressed as the number of spermatozoa per milliliter. Motility was assessed by placing a drop of fresh suspension on a pre-warmed slide at 37°C, and at least 200 spermatozoa per sample were categorized as progressively motile, non-progressively motile, or immotile. For morphology, smears were prepared, air-dried, and stained with eosin Y. A minimum of 200 spermatozoa were examined under oil immersion (×1000) to identify normal forms and classify abnormalities in the head, midpiece, and tail. This standardized approach ensured a comprehensive and reproducible evaluation of sperm quality (9).

2.1.6. SeNPs

TAC of testicular tissue was assessed using a commercial assay kit provided by Kiazist Life Sciences Co. (Iran), following Erel’s protocol (17). The commercial assay is based on the reduction of a colored radical cation, where the decrease in absorbance at a specific wavelength, measured via spectrophotometry, reflects the antioxidant capacity of the sample. 24 hr after radiation exposure, testicular tissues were excised and mechanically homogenized in an appropriate buffer. The observed decrease in color intensity correlated with the concentration of antioxidant compounds. TAC levels were quantified and reported as micromolar Trolox equivalents per milligram of tissue protein (µmol Trolox Eq/mg protein).

2.1.5.2. TOS value

TOS in testicular tissue was quantified using a commercial assay kit from Kiazist Life Sciences (Iran), based on the protocol originally described by Erel (18). This method involves the oxidation of ferrous ions to ferric ions in the presence of oxidizing agents, followed by quantification with xylenol orange. TOS values were calculated as micromolar hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) equivalents per milligram of tissue protein, after calibration against a H₂O₂ standard.

2.1.5.3. OSI value

OSI was calculated by dividing the TOS value by TAC value and multiplying by 100 to express the result as a percentage. This index quantitatively assessed oxidative stress intensity, reflecting the balance between oxidant and antioxidant systems within the biological sample.

2.1.5.4. Histological evaluation

Histological evaluation of testicular tissue was performed using standard staining techniques, primarily hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (14). H&E staining is widely accepted as the standard method for the microscopic examination of fixed, processed, embedded, and sectioned tissues. Additionally, Masson’s trichrome stain was utilized for histological evaluation. Briefly, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-µm-thick slices using a microtome. These sections were subsequently deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained using Masson’s trichrome staining according to established protocols. After staining, the prepared slides were analyzed by light microscopy. In H&E-stained tissues, nucleic acids typically appear dark blue, while proteins exhibit red, pink, or orange shades.

2.1.5.5. Sperm parameters evaluation

Sperm analysis was performed in accordance with the World Health Organiation Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (19), with adaptations for rats. Following dissection, the cauda epididymis was placed in HEPES-buffered DMEM to allow spermatozoa to disperse. Sperm concentration was determined using a hemocytometer, with results expressed as the number of spermatozoa per milliliter. Motility was assessed by placing a drop of fresh suspension on a pre-warmed slide at 37°C, and at least 200 spermatozoa per sample were categorized as progressively motile, non-progressively motile, or immotile. For morphology, smears were prepared, air-dried, and stained with eosin Y. A minimum of 200 spermatozoa were examined under oil immersion (×1000) to identify normal forms and classify abnormalities in the head, midpiece, and tail. This standardized approach ensured a comprehensive and reproducible evaluation of sperm quality (9).

2.1.6. SeNPs

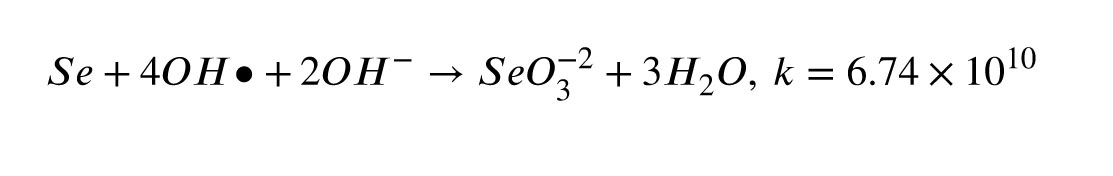

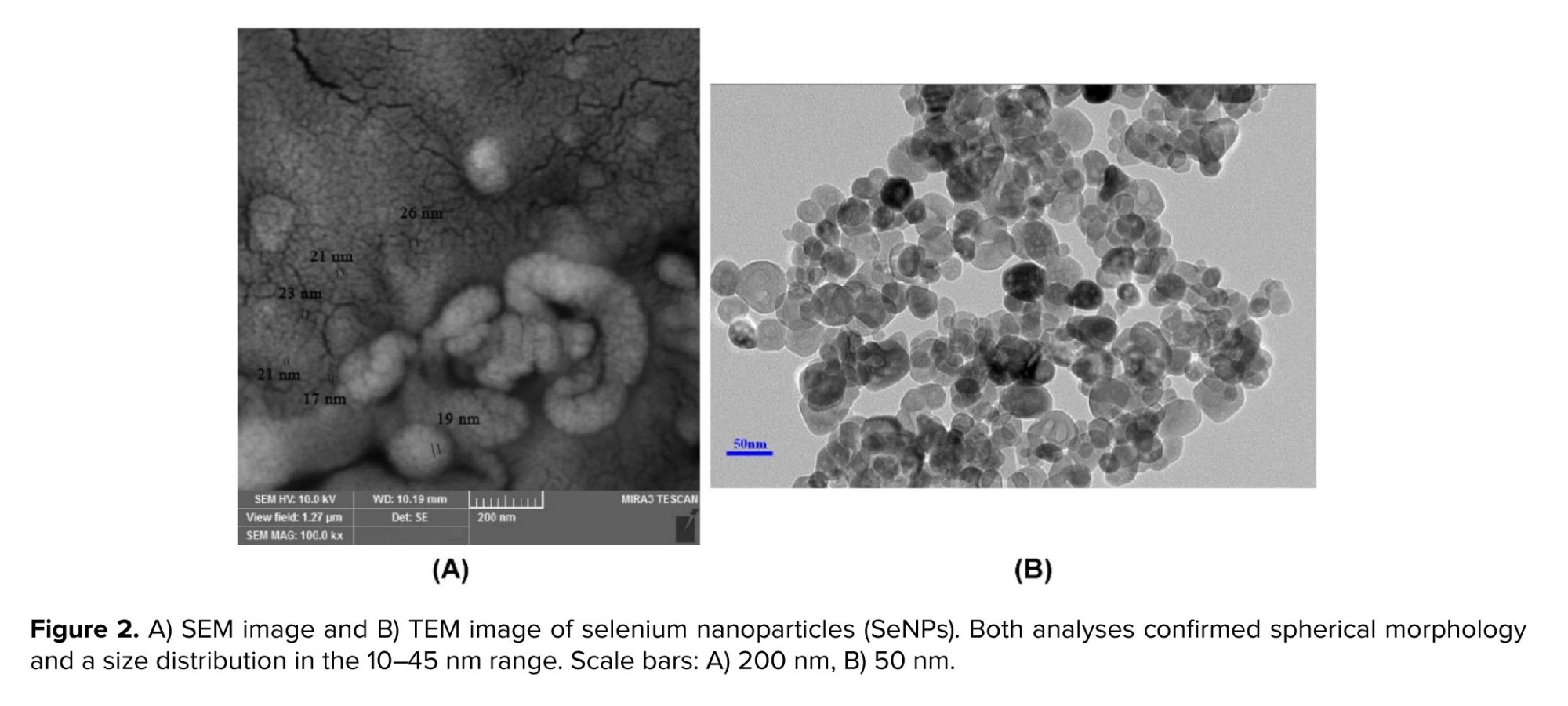

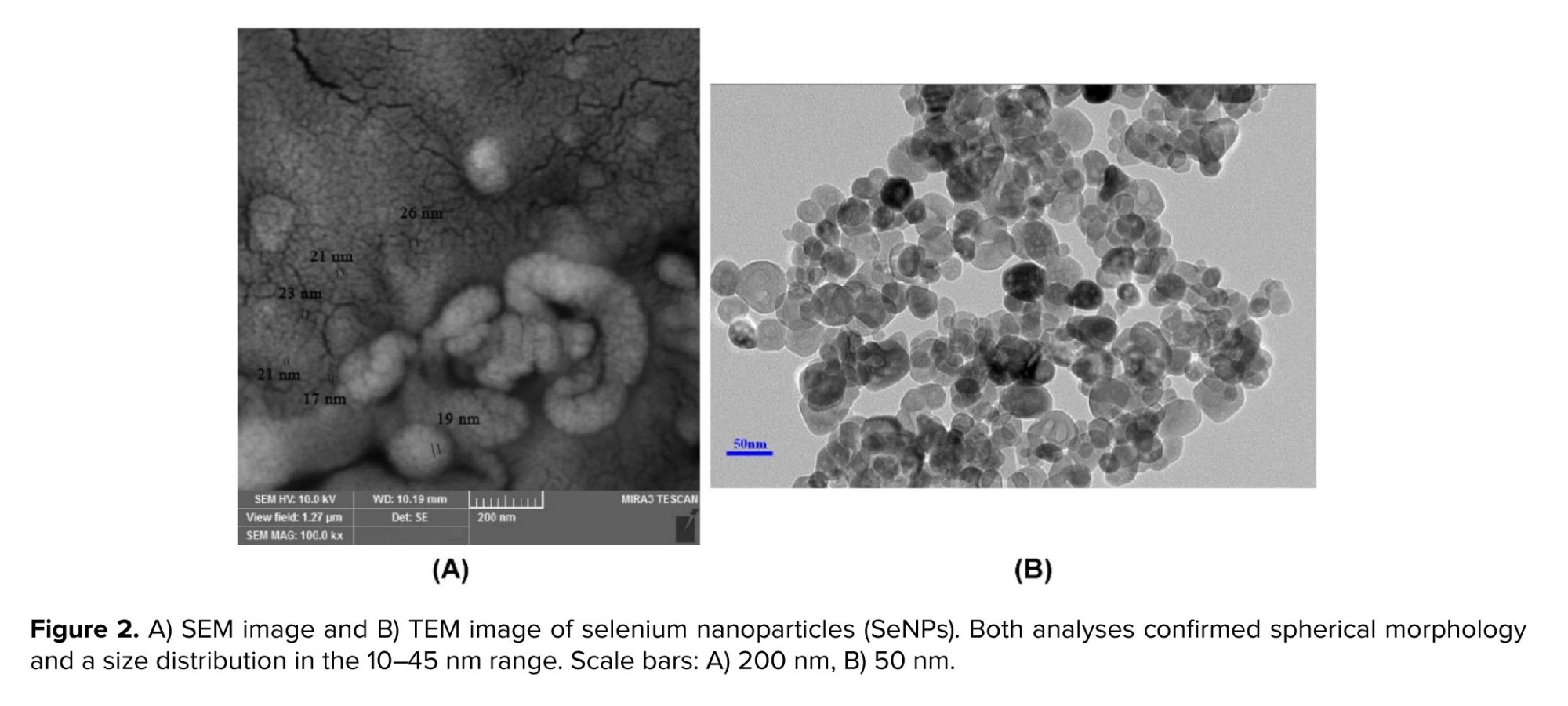

The article employs 99.99% pure SeNPs from Iranian Nanomaterials Pioneers Co., characterized by diameters between 10 and 45 nanometers. The morphology and size of SeNPs were confirmed in this study using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The SEM images showed the nanoscale spherical morphology with diameters consistent with the supplier’s specifications (Figure 2A), while TEM provided high-resolution confirmation of particle dispersion and uniformity (Figure 2B). SeNPs can scavenge OH• through the following reaction (20):

2.2. Simulation step

2.2. Simulation step

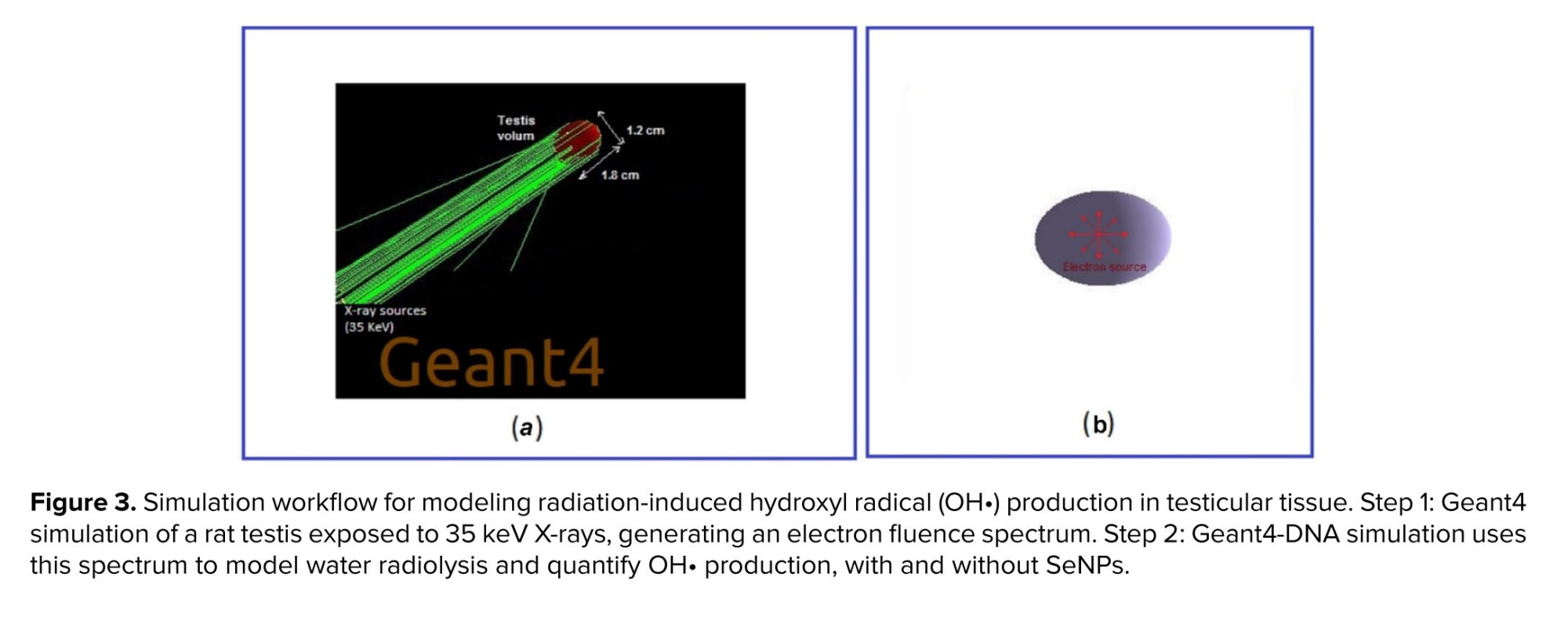

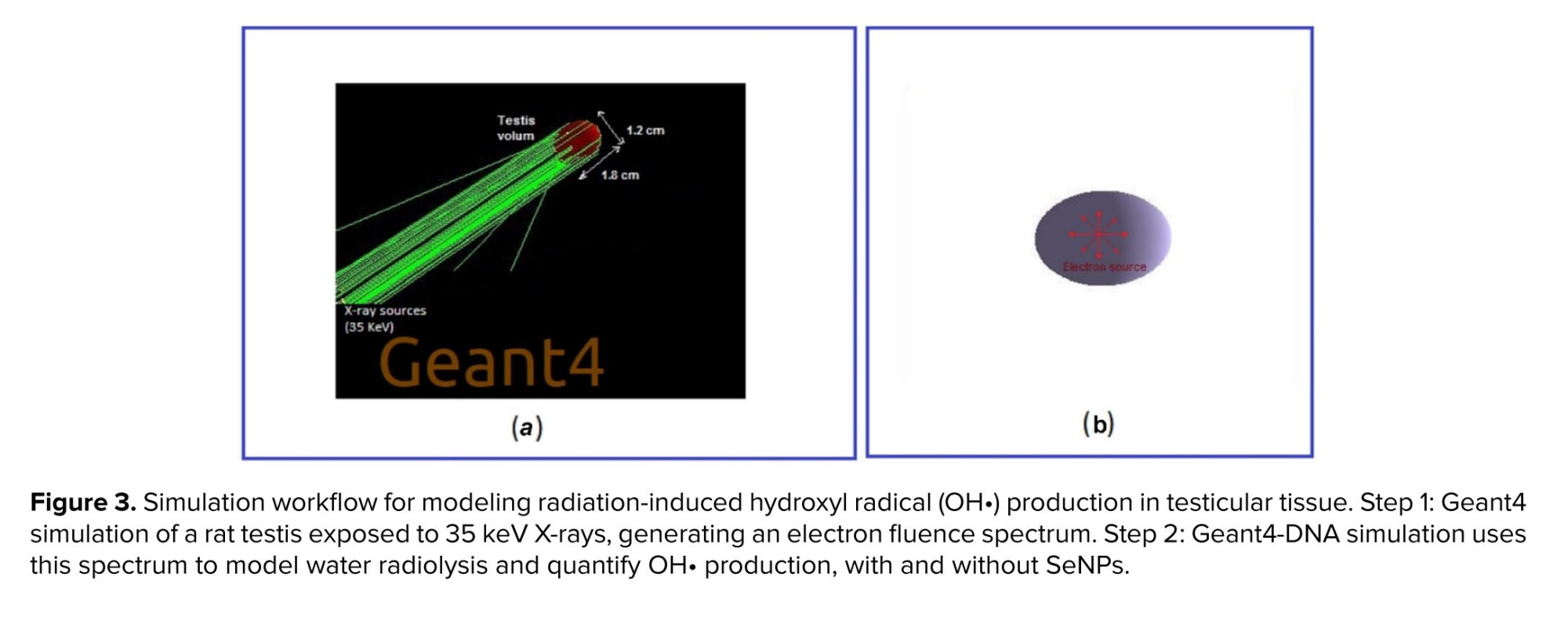

This phase simulated the sequential stages of radiation interaction: physical, physicochemical, and chemical processes in water. Initially, X-rays interacted with water molecules, causing excitation and ionization (physical stage), which resulted in the formation of radiolytic species during the physicochemical stage. These species subsequently diffused and participated in reactions throughout the heterogeneous chemical stage, where the presence of SeNPs modified the reaction dynamics.

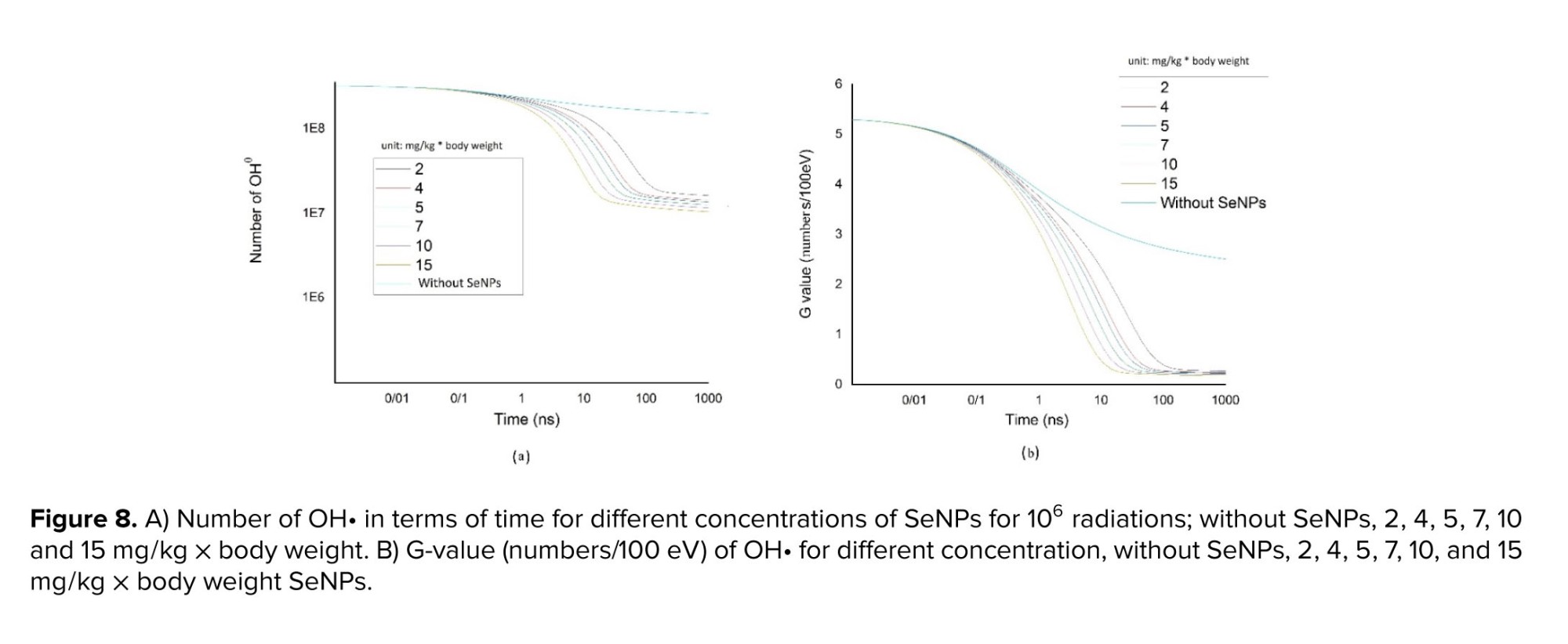

2.2.1. G-value determination

The G-value quantified the number of radical species, products, or molecules produced per 100 electron volts of energy absorbed (21). In this study, we simulated the production of free OH• and calculated the corresponding G-values during the chemical stage for various SeNPs concentrations based on 106 radiation beams.

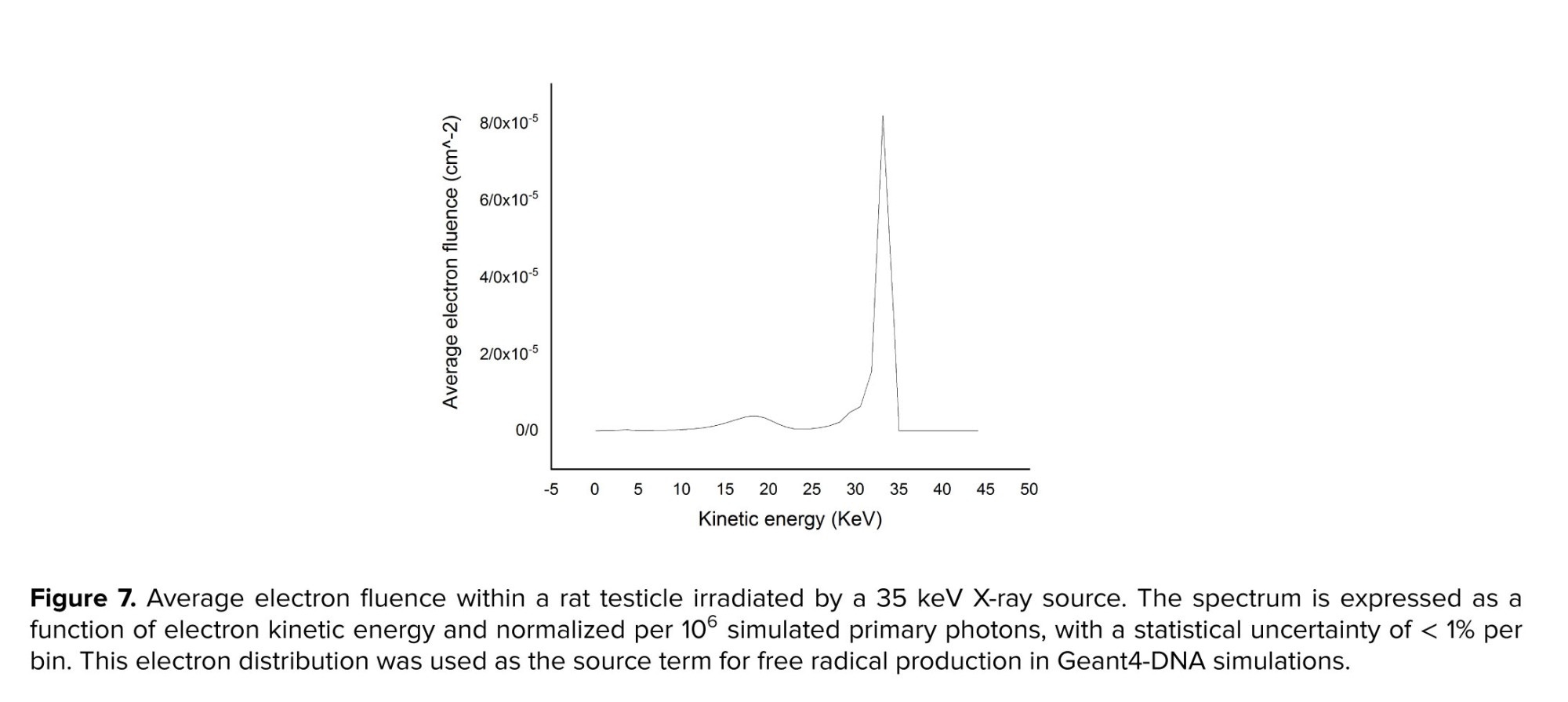

X-rays interacted with water, generated a range of secondary electrons, which, in turn, produced reactive free radicals. To model the influence of SeNPs on hydroxyl radical generation, a 2-stage computational approach was employed:

2.2.1. G-value determination

The G-value quantified the number of radical species, products, or molecules produced per 100 electron volts of energy absorbed (21). In this study, we simulated the production of free OH• and calculated the corresponding G-values during the chemical stage for various SeNPs concentrations based on 106 radiation beams.

X-rays interacted with water, generated a range of secondary electrons, which, in turn, produced reactive free radicals. To model the influence of SeNPs on hydroxyl radical generation, a 2-stage computational approach was employed:

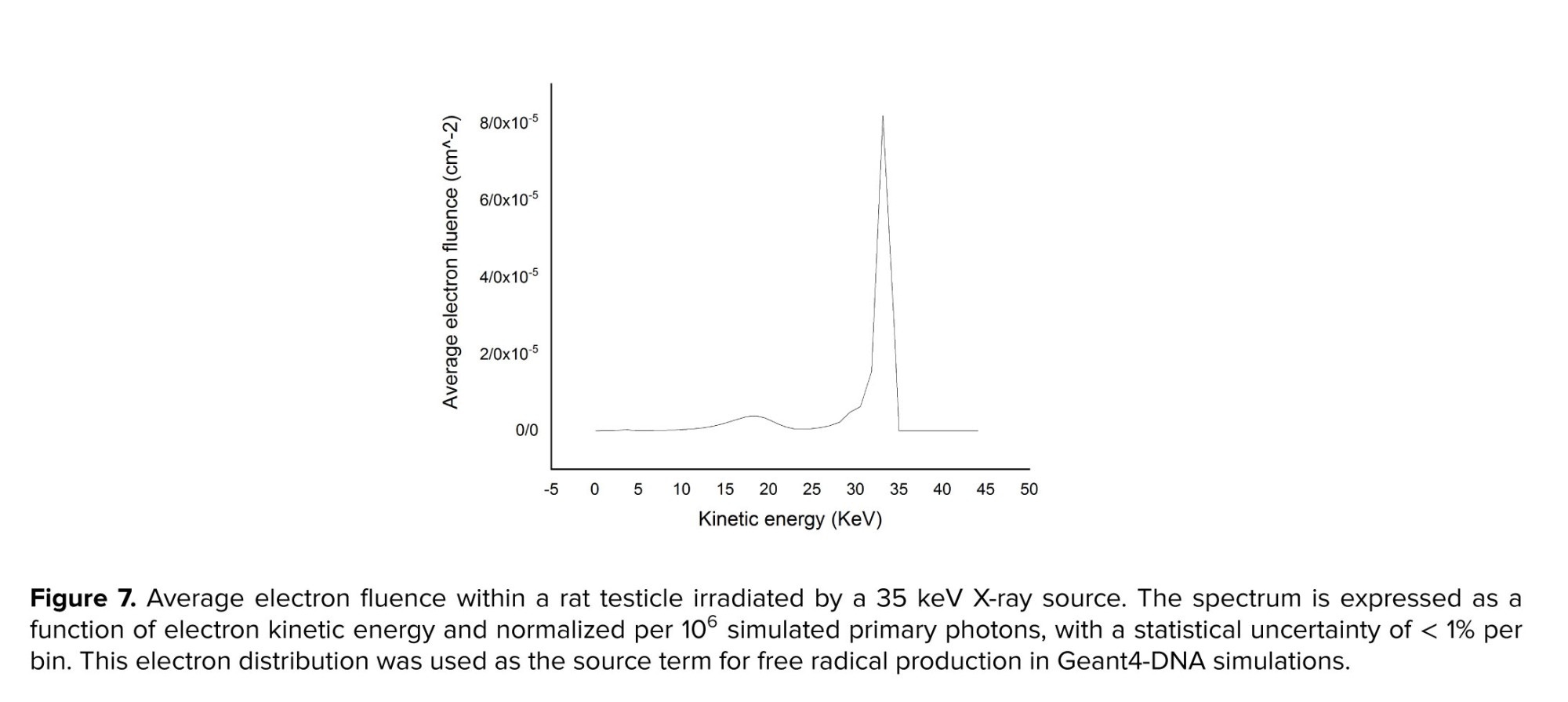

- Geant4 simulation: Geant4 (v11.2.1) was used to obtain the average electron fluence spectral distribution inside a testicle irradiated with 35 keV parallel X-rays.

- Geant4-DNA simulation: using the spectral distribution derived from the Geant4 results, Geant4-DNA (v11.2.1) was employed to simulate the radiolysis process in the presence of SeNPs.

2.2.2. Average electron fluence calculation

The average electron fluence, ∅ d ∅ / dE

In the first stage, a rat testis was irradiated with parallel 35 keV X-rays incident on one face, simulating 106 photons (Figure 3a). Subsequently, for the Geant4-DNA radiolysis simulation, an isotropic point-like electron source with a spectrum derived from a previous Geant4 simulation was positioned at the center of a testis volume containing 20 nm spherical SeNPs at concentrations from 2-15 mg/L (Figure 3b). The number of OH• produced, and the corresponding G-values were computed for each SeNP concentration.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This animal experimental study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the national guidelines for working with laboratory animals. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.UMA.REC.1403.031).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This animal experimental study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the national guidelines for working with laboratory animals. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.UMA.REC.1403.031).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

This section presented findings from both the experimental and simulation components of the study. The experimental results included differences in testicular weight, body weight gain, histopathological changes, oxidative stress markers (TOS, TAC, OSI), and sperm parameter evaluations. All animals tolerated the irradiation and handling procedures well, with no mortality or exclusions; all 42 rats completed the experimental protocol and were included in the final analyses (attrition = 0%). The simulation results reported the average electron fluence and G-values, quantifying hydroxyl radical scavenging efficiency.

3.1. Difference in testicular weight

3.1. Difference in testicular weight

SeNP administration reduced testicular weight asymmetry (> 5% difference) from 83.33%-41.66% of cases (50% relative reduction) and decreased the maximum observed difference from 16.33%-11.11% (32% relative reduction).

Previous studies have generally reported that no significant difference was observed in weight between the left and right testicles in healthy rodents (23). In the present study, the control group showed no measurable difference between testes (0% of cases with > 5% weight difference; maximum difference = 0.00%). In contrast, irradiated rats without SeNPs developed testicular weight asymmetry in 83.33% of cases, with a maximum difference of 16.33%. Administration of SeNPs before irradiation markedly attenuated these changes, reducing the occurrence of asymmetry (> 5% difference) to 41.66% of cases (50% relative reduction) and decreasing the maximum difference to 11.11% (32% relative reduction). These results suggested that SeNP treatment preserved bilateral testicular weight symmetry following radiation exposure.

3.2. Weight gain

Previous studies have generally reported that no significant difference was observed in weight between the left and right testicles in healthy rodents (23). In the present study, the control group showed no measurable difference between testes (0% of cases with > 5% weight difference; maximum difference = 0.00%). In contrast, irradiated rats without SeNPs developed testicular weight asymmetry in 83.33% of cases, with a maximum difference of 16.33%. Administration of SeNPs before irradiation markedly attenuated these changes, reducing the occurrence of asymmetry (> 5% difference) to 41.66% of cases (50% relative reduction) and decreasing the maximum difference to 11.11% (32% relative reduction). These results suggested that SeNP treatment preserved bilateral testicular weight symmetry following radiation exposure.

3.2. Weight gain

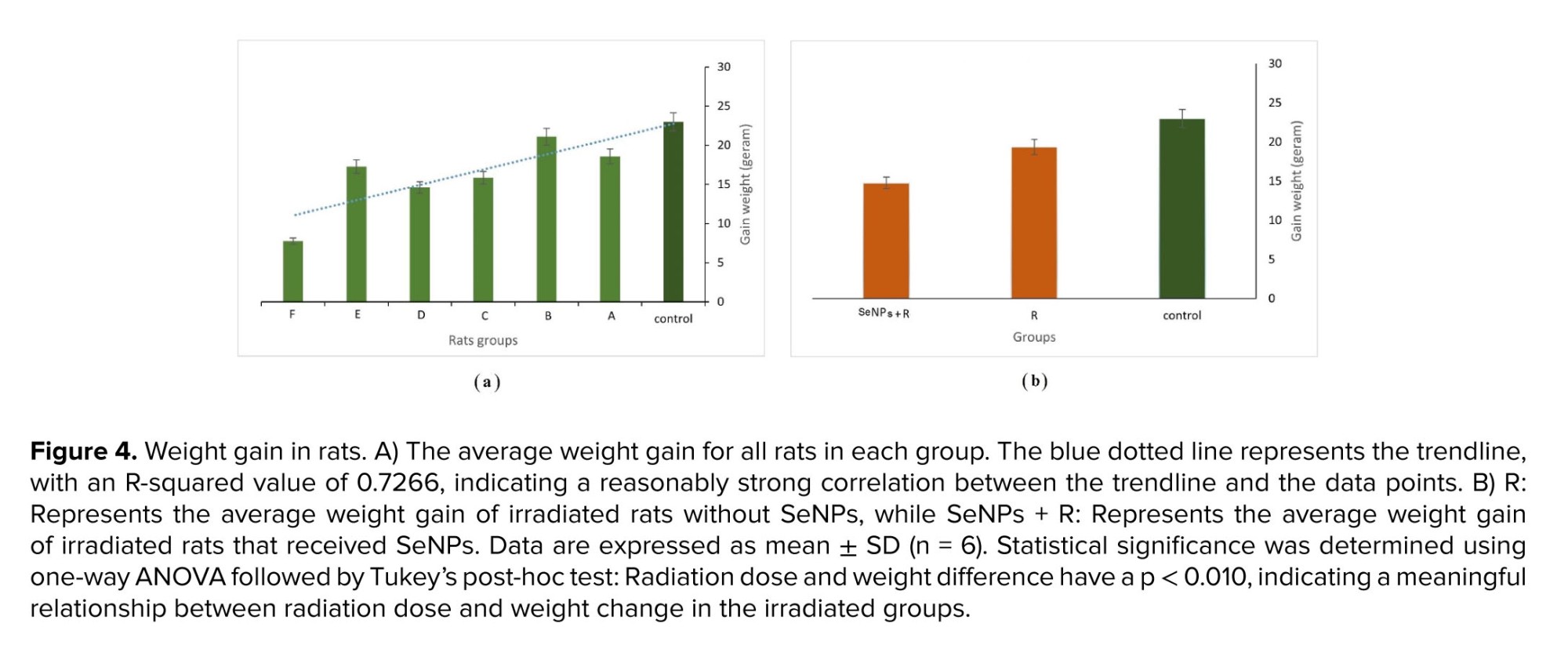

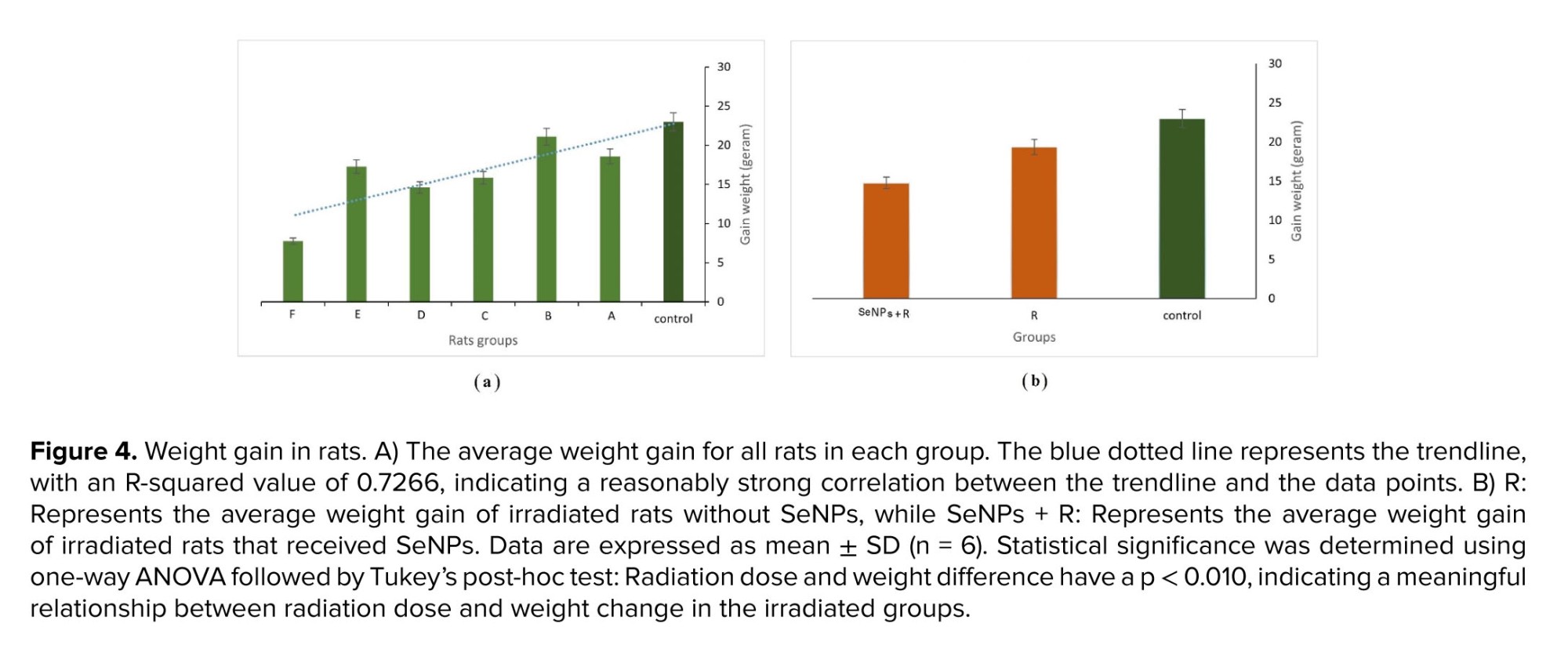

Several studies have examined the effects of radiation on rat weight gain, demonstrating a decrease in body weight gain with increasing radiation doses (24). In this study, rat weights were measured at the beginning and end of the radiation period. Figure 4a shows the average weight gain of rats in each group. Radiation exposure led to a significant decrease in weight gain among rats, particularly evident at doses higher than 0.4 Gy (p < 0.050 vs. control). Group F, which received the highest dose, exhibited the lowest weight gain. Generally, weight gain decreases with increasing absorbed dose, as indicated by the trendline (blue dotted line). The R-squared value of the trendline (0.7266) reflected a relatively strong correlation between the trendline and the data points. Additionally, rats exposed to radiation and treated with SeNPs showed significantly lower weight gain compared to rats exposed to radiation alone (p < 0.05), despite demonstrating protective effects in other parameters (Figure 4b).

3.3. Histopathological changes result

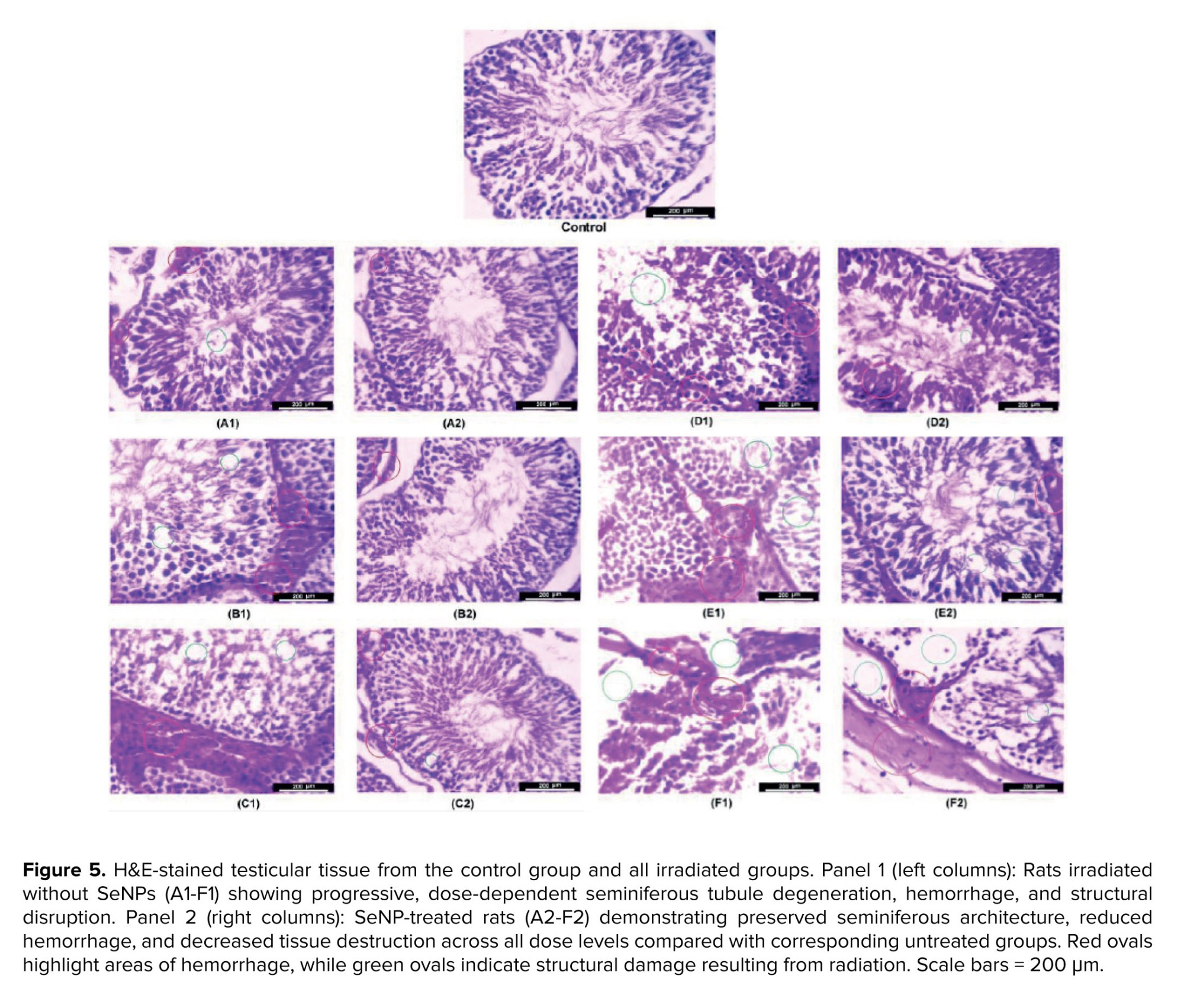

3.3. Histopathological changes result

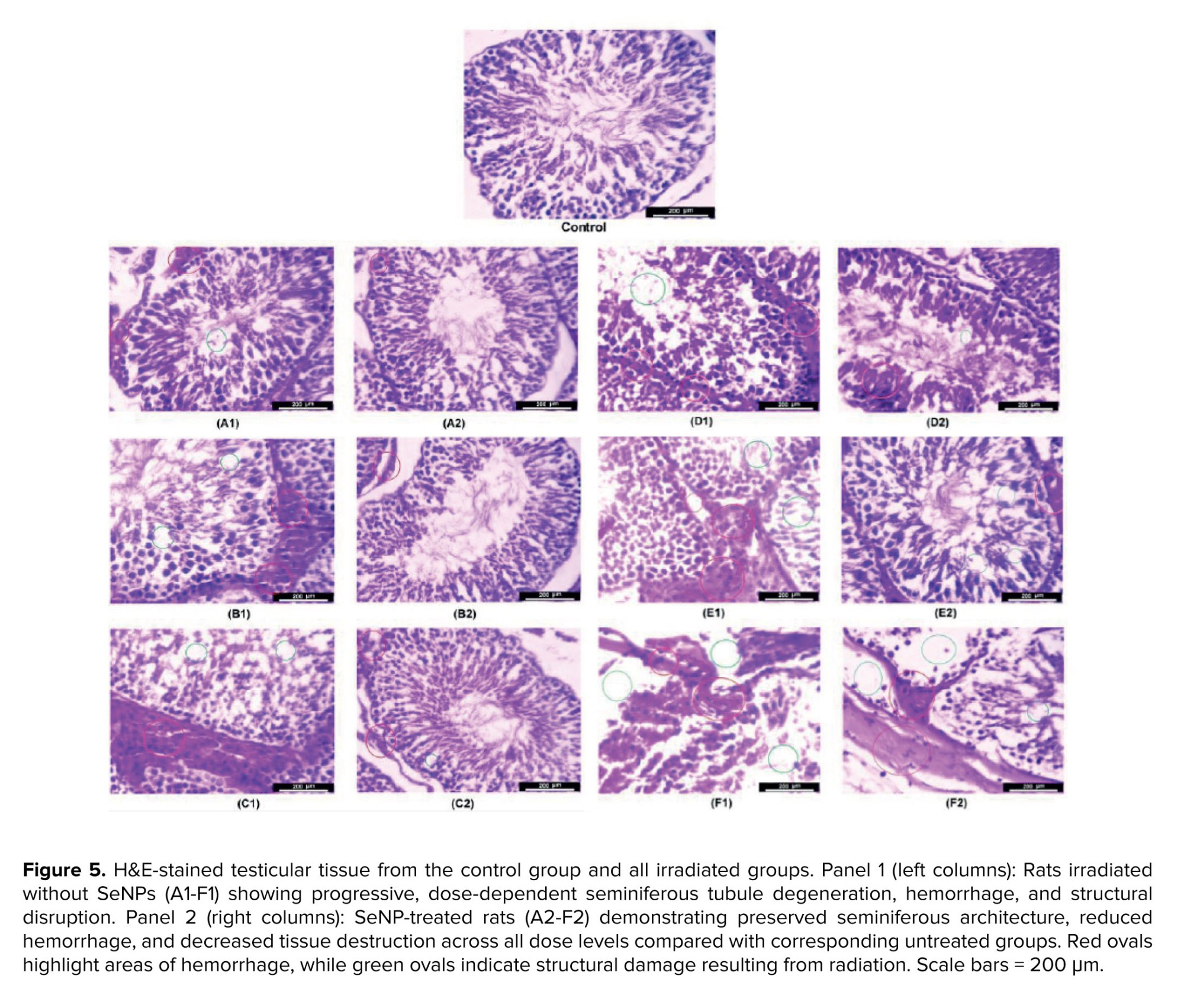

Figure 5 present histopathological examinations of testicular tissue across experimental groups. Panel 1 (left columns) shows irradiated rats without SeNPs, while panel 2 (right columns) displays rats pre-treated with SeNPs. In all groups, the severity of histopathological lesions increased with dose, from top to bottom.

In the upper panels (groups A-C), higher radiation doses led to progressively greater vascular congestion, interstitial hemorrhage, and vacuolization of Sertoli cells in A1, B1, and C1, respectively. In some tubules, germinal epithelium disorganization and detachment from the basement membrane were observed, along with pyknosis of spermatogonia at higher doses. In contrast, the corresponding SeNP-treated groups (A2, B2, C2) exhibited better tissue preservation, with more intact seminiferous tubule architecture, reduced congestion, and fewer degenerative changes in the germinal epithelium.

In the lower panels (groups D-F), increasing doses resulted in escalating germ cell depletion, thinning of the germinal epithelium, and widening of interstitial spaces in D1, E1, and F1. At the highest dose, some tubules were completely devoid of germ cells, with only Sertoli cell remnants remaining. However, the SeNP-treated groups (D2, E2, F2) demonstrated markedly better structural integrity. Many tubules retained normal epithelial layering, exhibited less interstitial edema, and showed preservation of the blood-testis barrier. Even at the highest radiation dose, some seminiferous tubules remained intact in F2 compared to F1.

Overall, testicular histology, ncluding parenchyma, seminiferous tubules, germinal epithelium, and interstitial tissue, was significantly better preserved in SeNP-treated groups than in untreated ones, correlating with the improved sperm parameters and oxidative stress profiles observed in these animals.

3.4. TOS, TAC, and OSI results

In the upper panels (groups A-C), higher radiation doses led to progressively greater vascular congestion, interstitial hemorrhage, and vacuolization of Sertoli cells in A1, B1, and C1, respectively. In some tubules, germinal epithelium disorganization and detachment from the basement membrane were observed, along with pyknosis of spermatogonia at higher doses. In contrast, the corresponding SeNP-treated groups (A2, B2, C2) exhibited better tissue preservation, with more intact seminiferous tubule architecture, reduced congestion, and fewer degenerative changes in the germinal epithelium.

In the lower panels (groups D-F), increasing doses resulted in escalating germ cell depletion, thinning of the germinal epithelium, and widening of interstitial spaces in D1, E1, and F1. At the highest dose, some tubules were completely devoid of germ cells, with only Sertoli cell remnants remaining. However, the SeNP-treated groups (D2, E2, F2) demonstrated markedly better structural integrity. Many tubules retained normal epithelial layering, exhibited less interstitial edema, and showed preservation of the blood-testis barrier. Even at the highest radiation dose, some seminiferous tubules remained intact in F2 compared to F1.

Overall, testicular histology, ncluding parenchyma, seminiferous tubules, germinal epithelium, and interstitial tissue, was significantly better preserved in SeNP-treated groups than in untreated ones, correlating with the improved sperm parameters and oxidative stress profiles observed in these animals.

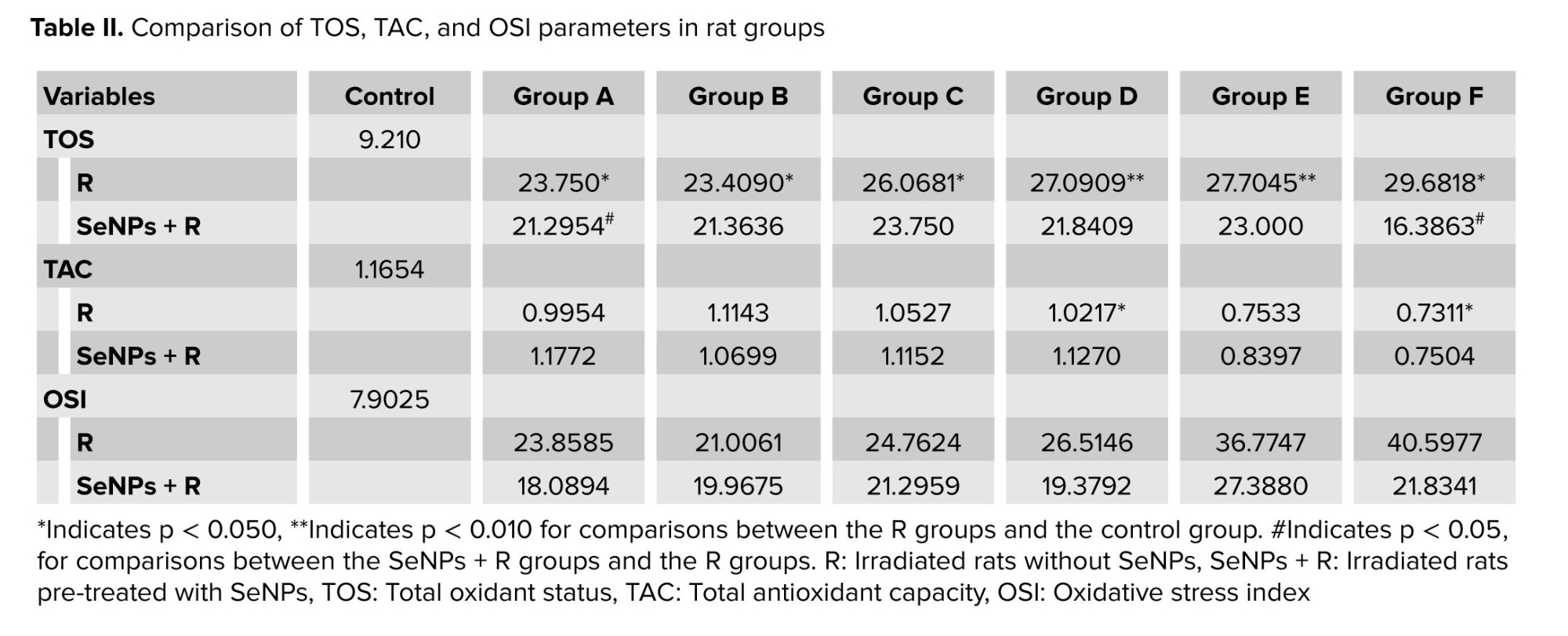

3.4. TOS, TAC, and OSI results

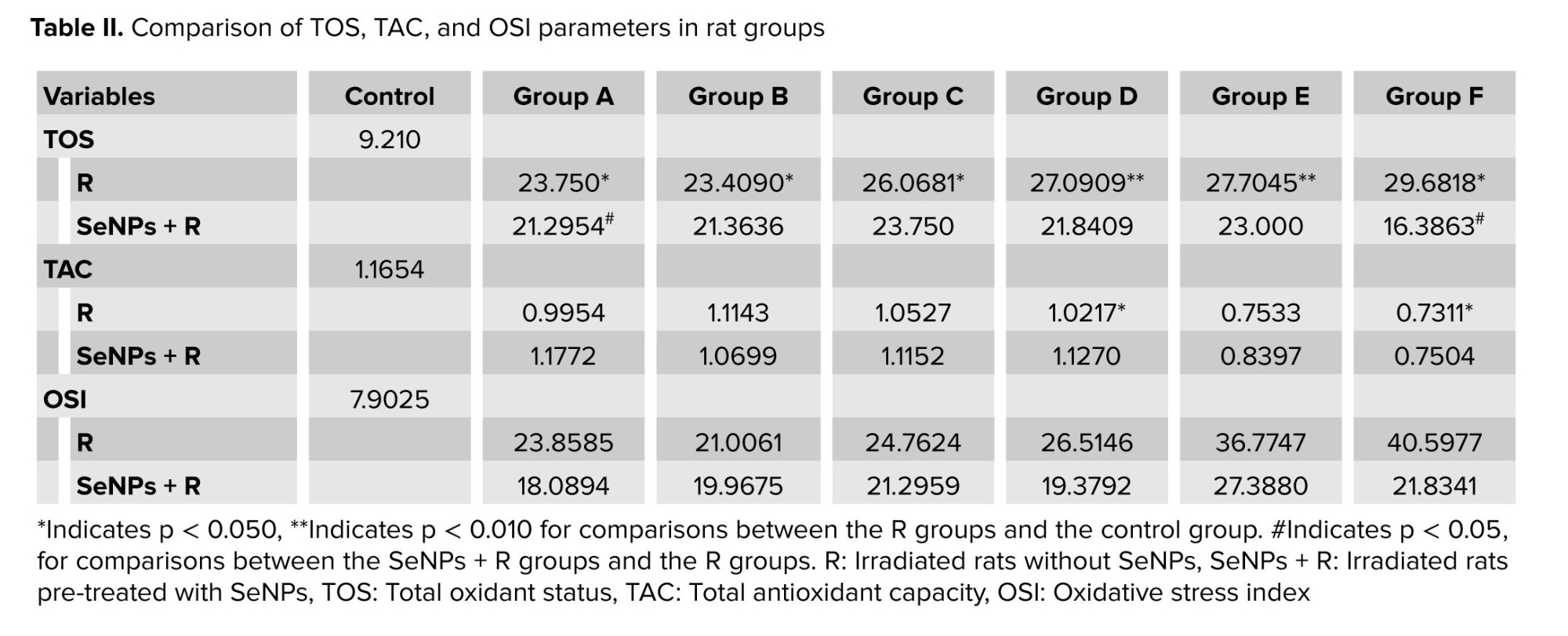

Comparing the control and R groups (irradiation groups without SeNPs), statistically significant differences were found in TOS (p = 0.005) and TAC (p = 0.044) values, with TOS increasing and TAC decreasing after radiation exposure (Table II). The effect of radiation on the TOS value was significant when comparing the R groups with the control group, with significant reduction in TAC values observed in groups D and F (Table II). Overall, results showed that after radiation exposure, TOS and OSI increased while TAC decreased. Additionally, increasing radiation dose led to higher TOS and OSI values and lower TAC values. Notably, SeNPs generally reduced TOS and OSI values while raising TAC values, as demonstrated in table II.

3.5. Sperm parameters evaluation results

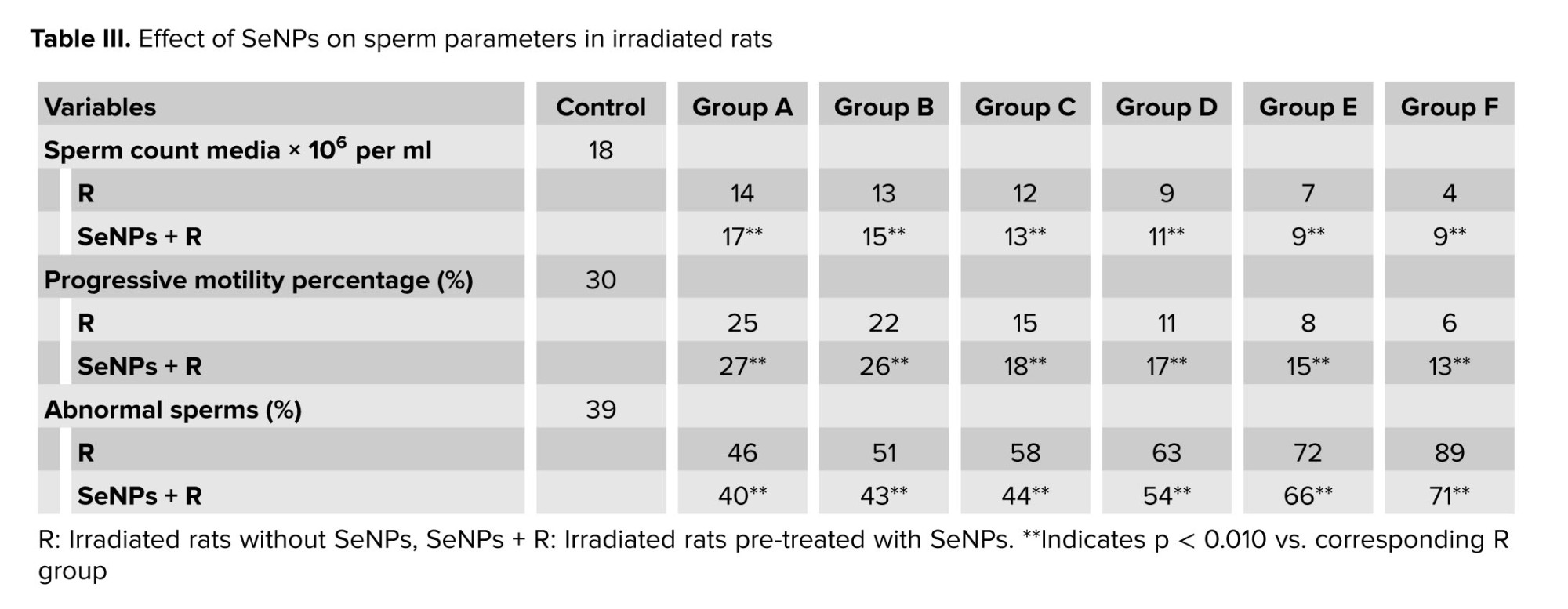

3.5. Sperm parameters evaluation results

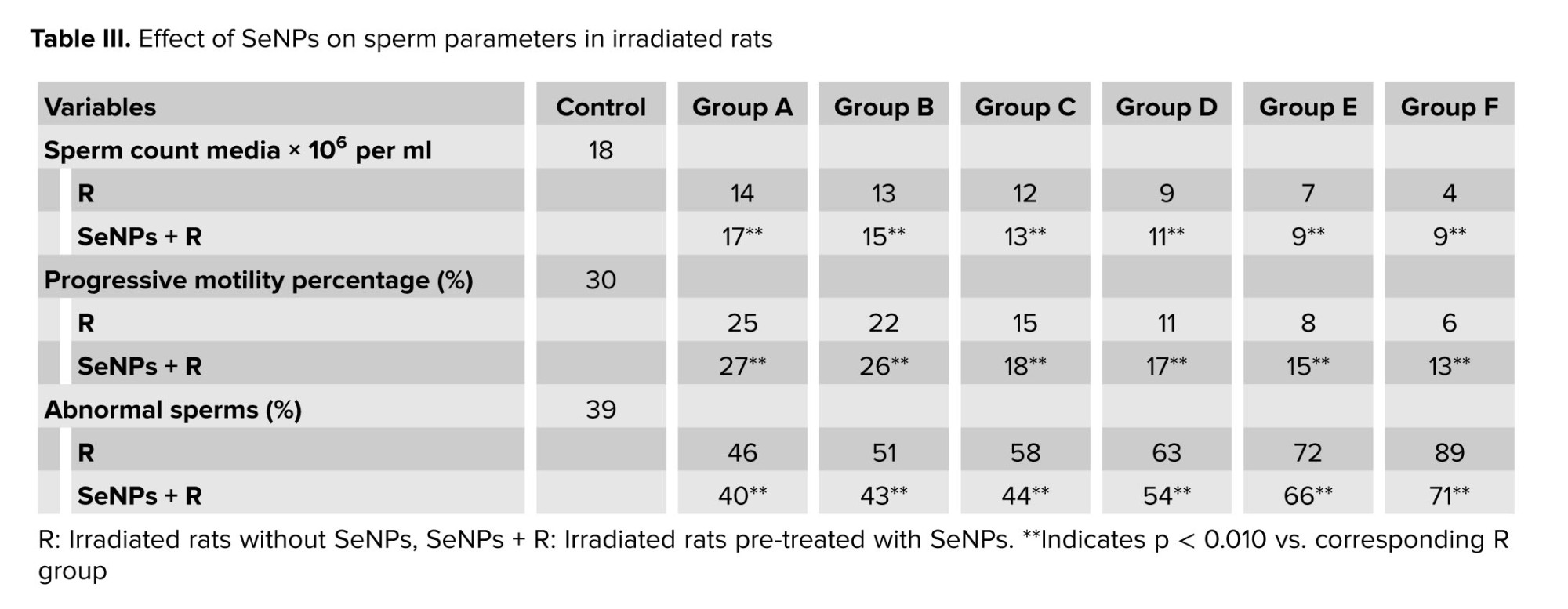

Table III presents the sperm count, median progressive motility, and abnormal sperm percentage for each group, compared with the control group.

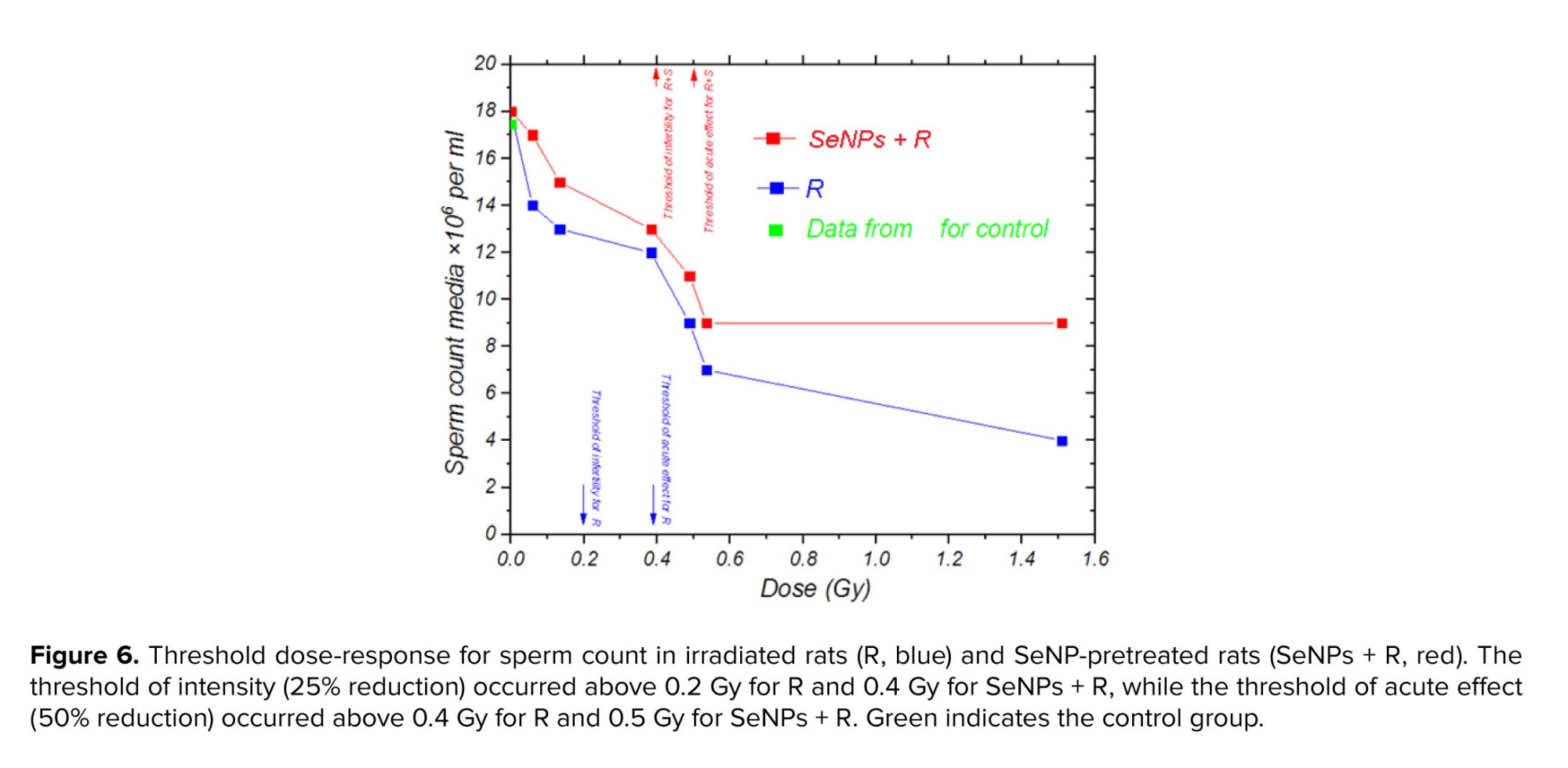

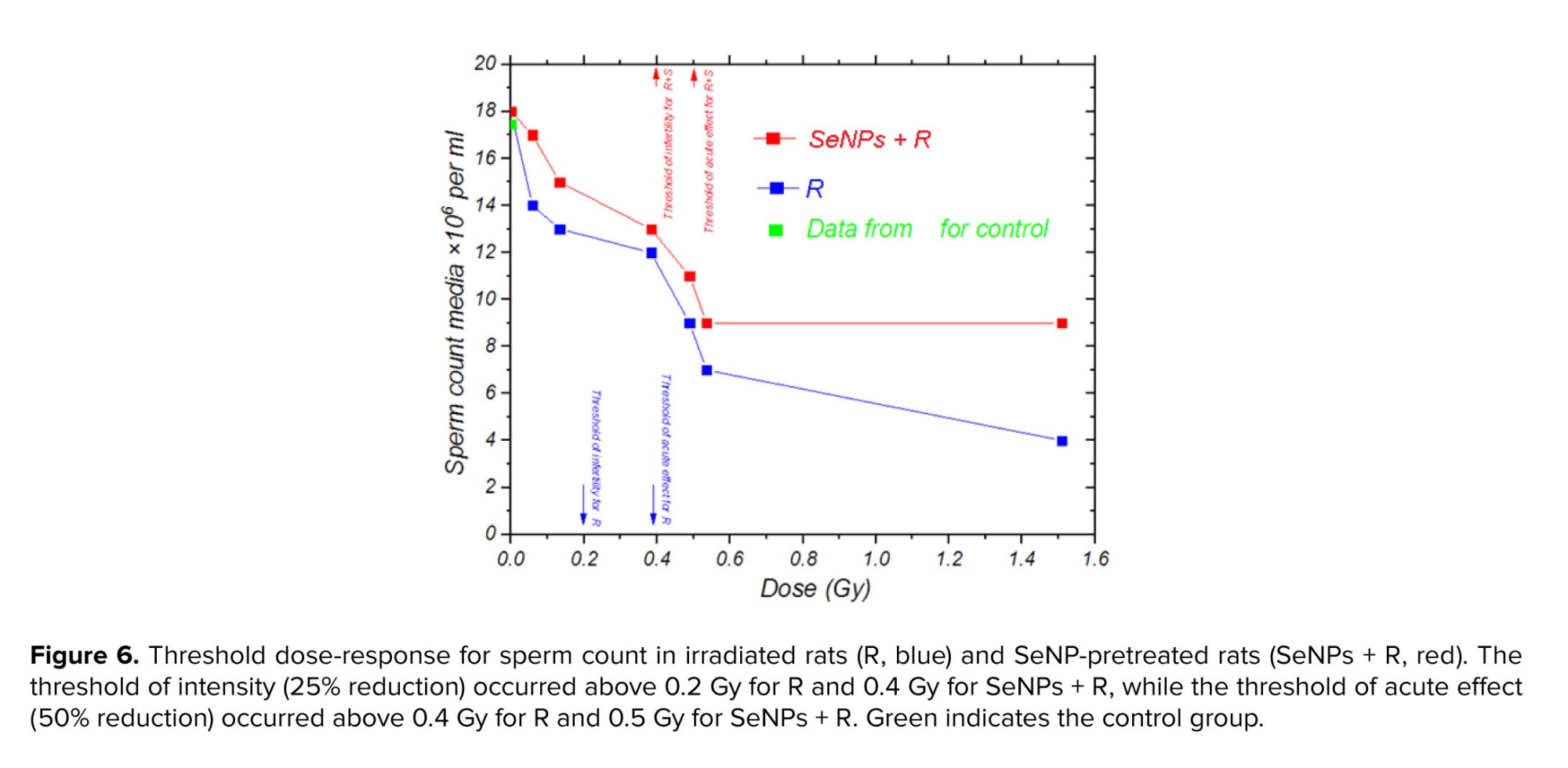

Across all the groups exposed to radiation, a significant decrease in sperm count was observed compared to the control group (ranging from 6-87%). Additionally, as indicated in table III, the sperm progressive motility decreased significantly with increasing absorbed dose compared with groups receiving lower radiation doses and control group. Conversely, in rats receiving SeNPs, both sperm count (increasing between 7% and 55%) and sperm motility (increasing between 2% and 7%) improved significantly compared to the R groups alone. Moreover, the proportion of abnormal sperm increased significantly in R groups compared to the control group (ranging from 7-50%), whereas the presence of SeNPs reduced abnormal sperm numbers compared to R groups (by 6-18%).

The laboratory results of sperm count, as illustrated in figure 6, demonstrated a 25% reduction at doses above 0.2 Gy (0.4 Gy in SeNP-treated rats), highlighting the high sensitivity of the male reproductive system to relatively low radiation exposures. A more pronounced decline of 50% was observed at doses exceeding 0.4 Gy (0.5 Gy in SeNP-treated rats). These findings suggest that infertility in rats may occur at doses above 0.2 Gy, with acute and severe alterations becoming evident beyond 0.4 Gy. The delayed onset of these effects in SeNP-treated rats likely reflects the antioxidant and radioprotective properties of SeNPs, which scavenge free radicals, attenuate oxidative stress, and protect DNA integrity. This result supports the potential of SeNPs as a mitigating agent against radiation-induced reproductive toxicity.

3.6. Average electron fluence

Across all the groups exposed to radiation, a significant decrease in sperm count was observed compared to the control group (ranging from 6-87%). Additionally, as indicated in table III, the sperm progressive motility decreased significantly with increasing absorbed dose compared with groups receiving lower radiation doses and control group. Conversely, in rats receiving SeNPs, both sperm count (increasing between 7% and 55%) and sperm motility (increasing between 2% and 7%) improved significantly compared to the R groups alone. Moreover, the proportion of abnormal sperm increased significantly in R groups compared to the control group (ranging from 7-50%), whereas the presence of SeNPs reduced abnormal sperm numbers compared to R groups (by 6-18%).

The laboratory results of sperm count, as illustrated in figure 6, demonstrated a 25% reduction at doses above 0.2 Gy (0.4 Gy in SeNP-treated rats), highlighting the high sensitivity of the male reproductive system to relatively low radiation exposures. A more pronounced decline of 50% was observed at doses exceeding 0.4 Gy (0.5 Gy in SeNP-treated rats). These findings suggest that infertility in rats may occur at doses above 0.2 Gy, with acute and severe alterations becoming evident beyond 0.4 Gy. The delayed onset of these effects in SeNP-treated rats likely reflects the antioxidant and radioprotective properties of SeNPs, which scavenge free radicals, attenuate oxidative stress, and protect DNA integrity. This result supports the potential of SeNPs as a mitigating agent against radiation-induced reproductive toxicity.

3.6. Average electron fluence

Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of average electron fluence within a testicular volume exposed to X-ray irradiation, as simulated using Geant4. The fluence spectrum reflected the kinetic energy of secondary electrons generated by 35 keV incident photons. This electron spectrum was subsequently used as the input for Geant4-DNA chemical stage simulations to estimate hydroxyl radical yields and G-values.

3.7. G-value result

The number of OH• species and G-values exhibit a decreased over time in the presence of SeNPs, as shown by figure 8a and b. Additionally, both figures demonstrated a further decline with increasing SeNPs concentration, with the steepest decline observed in time intervals ranging from 0.1-100 nanoseconds. The subsequent section will compare and analyze these simulation results with experimental data available from other studies.

4. Discussion

4. Discussion

Our experimental results demonstrate that SeNP pre-treatment effectively mitigated radiation-induced testicular damage, preserving the structural integrity of seminiferous tubules, germinal epithelium, and interstitial parenchyma. These structures were deliberately selected for evaluation because they are the functional units of spermatogenesis and androgen production, and are highly susceptible to oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by ionizing radiation.

Biochemically, SeNP administration reduced oxidative stress markers (TOS, OSI) and increased TAC by 2.5-15.5%, indicating restoration of redox balance. This finding is consistent with earlier reports on SeNP-mediated protection against cisplatin- and γ-radiation-induced oxidative damage (25) and is further supported by recent evidence showing that SeNPs scavenge ROS, stabilize cellular membranes, and modulate pro- and anti-apoptotic pathways (8). Other studies also emphasized the antioxidant and DNA-protective effects of SeNPs, particularly through regulation of redox signaling pathways and suppression of oxidative stress-mediated injury (26). Additional evidence highlighted the relevance of selenium and SeNPs in male fertility, demonstrating their ability to support spermatogenesis, improve sperm quality, and protect reproductive tissues from oxidative stress (27).

Histopathological findings paralleled these biochemical trends. Radiation-only groups showed marked degeneration of seminiferous tubules, germ cell depletion, and structural disorganization, while SeNP-treated groups maintained tubule architecture, reduced lesion severity, and exhibited higher sperm counts (7-55% increase), motility (2-7% increase), and lower abnormal sperm rates (6-18% reduction). These outcomes are consistent with evidence that SeNPs mitigate testicular apoptosis by activating Nrf2-HO-1 signaling, reducing Bax and caspase-3 expression, and enhancing Bcl-2 levels in chemotherapy-exposed rats (6). Other studies also demonstrated that selenium compounds activate the p53 pathway, contributing to DNA repair and cell cycle regulation, mechanisms that may underlie the structural preservation observed in this study (28). Additional findings indicated that selenium status directly influences DNA stability and telomere integrity during spermatogenesis, supporting the notion that SeNPs may protect against genotoxic stress at the chromosomal level (29). These findings indicate that the threshold for acute testicular alterations in rats occurs at doses above 0.2 Gy, consistent with reports of acute testicular effects in humans above 0.3 Gy, underscoring both the high radiosensitivity of the gonads and the protective role of SeNPs (30).

Although SeNP administration consistently improved oxidative stress markers, sperm quality, and histological preservation, an unexpected trend was observed in body weight gain (Figure 4b), where irradiated-only animals showed slightly greater weight gain than SeNP-treated irradiated groups. This modest difference was likely attributable to selenium’s metabolic effects, such as modulation of thyroid hormone activity, lipid metabolism, and energy expenditure, as well as normal inter-group variability in food intake. Importantly, this pattern did not correspond to negative outcomes in reproductive parameters, oxidative balance, or tissue histology, indicating it represents a secondary metabolic observation rather than diminished radioprotective efficacy (6, 26).

Simulation results showed an 82-93% reduction in OH• per unit absorbed energy (G-value), closely matching experimental OH• scavenging efficiencies of ~97% previously reported (31). The close agreement between computational and in vivo findings reinforced the role of SeNPs as effective ROS scavengers. Moreover, this was consistent with broader conclusions that nanoparticle morphology, size, and surface chemistry can significantly influence antioxidant potency (32).

However, it should be noted that the present simulation focused exclusively on OH• radicals due to their high reactivity, short diffusion range, and established role as primary mediators of radiation-induced DNA and protein damage. Other ROS species, such as superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) and H₂O₂, were not modeled, even though biochemical studies suggested that SeNPs may also neutralize these radicals (8, 26, 27). Future computational work incorporating multiple ROS types would provide a more comprehensive understanding of SeNP-mediated radioprotection.

(i) ROS, particularly OH•, were scavenged at the nanoparticle surface via redox cycling between Se (0) and Se (IV) (8, 30); (ii) bioavailable selenium was provided to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses by supporting selenoproteins such as glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase, and activating Nrf2/ARE signaling, thereby increasing glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activity (8, 26, 32); (iii) suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling (e.g., NF-κB/TNF-α), was suppressed, which limited secondary ROS/reactive nitrogen species production (8, 26); and (iv) DNA damage responses were facilitated, including p53-mediated repair and cell cycle regulation (28). Available evidence suggested that these protective effects were predominantly indirect, arising from ROS scavenging and redox modulation, rather than from covalent DNA binding (27).

Notably, SeNP administration attenuated testicular weight loss by up to 50%, suggesting protection of both spermatogenic and endocrine compartments. While Leydig cells preservation was evident histologically, functional assessment of testosterone and gonadotropin levels should be included in future studies.

Overall, our data underscored SeNPs’ capacity to protect reproductive tissues through a combination of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and DNA repair-promoting mechanisms. Future research should focus on molecular endpoint analysis (e.g., Nrf2, P53, Bcl-2, caspase-3 expression), assessment of long-term fertility, and exploration of nanoparticle optimization strategies for maximal radioprotective efficacy in reproductive health contexts.

5. Conclusion

Biochemically, SeNP administration reduced oxidative stress markers (TOS, OSI) and increased TAC by 2.5-15.5%, indicating restoration of redox balance. This finding is consistent with earlier reports on SeNP-mediated protection against cisplatin- and γ-radiation-induced oxidative damage (25) and is further supported by recent evidence showing that SeNPs scavenge ROS, stabilize cellular membranes, and modulate pro- and anti-apoptotic pathways (8). Other studies also emphasized the antioxidant and DNA-protective effects of SeNPs, particularly through regulation of redox signaling pathways and suppression of oxidative stress-mediated injury (26). Additional evidence highlighted the relevance of selenium and SeNPs in male fertility, demonstrating their ability to support spermatogenesis, improve sperm quality, and protect reproductive tissues from oxidative stress (27).

Histopathological findings paralleled these biochemical trends. Radiation-only groups showed marked degeneration of seminiferous tubules, germ cell depletion, and structural disorganization, while SeNP-treated groups maintained tubule architecture, reduced lesion severity, and exhibited higher sperm counts (7-55% increase), motility (2-7% increase), and lower abnormal sperm rates (6-18% reduction). These outcomes are consistent with evidence that SeNPs mitigate testicular apoptosis by activating Nrf2-HO-1 signaling, reducing Bax and caspase-3 expression, and enhancing Bcl-2 levels in chemotherapy-exposed rats (6). Other studies also demonstrated that selenium compounds activate the p53 pathway, contributing to DNA repair and cell cycle regulation, mechanisms that may underlie the structural preservation observed in this study (28). Additional findings indicated that selenium status directly influences DNA stability and telomere integrity during spermatogenesis, supporting the notion that SeNPs may protect against genotoxic stress at the chromosomal level (29). These findings indicate that the threshold for acute testicular alterations in rats occurs at doses above 0.2 Gy, consistent with reports of acute testicular effects in humans above 0.3 Gy, underscoring both the high radiosensitivity of the gonads and the protective role of SeNPs (30).

Although SeNP administration consistently improved oxidative stress markers, sperm quality, and histological preservation, an unexpected trend was observed in body weight gain (Figure 4b), where irradiated-only animals showed slightly greater weight gain than SeNP-treated irradiated groups. This modest difference was likely attributable to selenium’s metabolic effects, such as modulation of thyroid hormone activity, lipid metabolism, and energy expenditure, as well as normal inter-group variability in food intake. Importantly, this pattern did not correspond to negative outcomes in reproductive parameters, oxidative balance, or tissue histology, indicating it represents a secondary metabolic observation rather than diminished radioprotective efficacy (6, 26).

Simulation results showed an 82-93% reduction in OH• per unit absorbed energy (G-value), closely matching experimental OH• scavenging efficiencies of ~97% previously reported (31). The close agreement between computational and in vivo findings reinforced the role of SeNPs as effective ROS scavengers. Moreover, this was consistent with broader conclusions that nanoparticle morphology, size, and surface chemistry can significantly influence antioxidant potency (32).

However, it should be noted that the present simulation focused exclusively on OH• radicals due to their high reactivity, short diffusion range, and established role as primary mediators of radiation-induced DNA and protein damage. Other ROS species, such as superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) and H₂O₂, were not modeled, even though biochemical studies suggested that SeNPs may also neutralize these radicals (8, 26, 27). Future computational work incorporating multiple ROS types would provide a more comprehensive understanding of SeNP-mediated radioprotection.

(i) ROS, particularly OH•, were scavenged at the nanoparticle surface via redox cycling between Se (0) and Se (IV) (8, 30); (ii) bioavailable selenium was provided to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses by supporting selenoproteins such as glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase, and activating Nrf2/ARE signaling, thereby increasing glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activity (8, 26, 32); (iii) suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling (e.g., NF-κB/TNF-α), was suppressed, which limited secondary ROS/reactive nitrogen species production (8, 26); and (iv) DNA damage responses were facilitated, including p53-mediated repair and cell cycle regulation (28). Available evidence suggested that these protective effects were predominantly indirect, arising from ROS scavenging and redox modulation, rather than from covalent DNA binding (27).

Notably, SeNP administration attenuated testicular weight loss by up to 50%, suggesting protection of both spermatogenic and endocrine compartments. While Leydig cells preservation was evident histologically, functional assessment of testosterone and gonadotropin levels should be included in future studies.

Overall, our data underscored SeNPs’ capacity to protect reproductive tissues through a combination of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and DNA repair-promoting mechanisms. Future research should focus on molecular endpoint analysis (e.g., Nrf2, P53, Bcl-2, caspase-3 expression), assessment of long-term fertility, and exploration of nanoparticle optimization strategies for maximal radioprotective efficacy in reproductive health contexts.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that SeNPs significantly mitigated X-ray-induced oxidative stress, preserving testicular function and sperm quality. Improvements in oxidative stress markers (reduced TOS and OSI, increased TAC) and histopathological findings confirmed SeNPs’ radioprotective potential. These effects align with their known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, supporting their promise in protecting reproductive health from radiation damage. However, the study was limited to doses up to 1.5 Gy. Future research should examine higher radiation levels, longer observation periods, and more complex biological models to understand SeNPs, protective mechanisms. Overall, SeNPs show strong potential as radioprotective agents, warranting further investigation.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. Concept and design: A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Data acquisition (physics experiments, rat irradiation, dosimetry, biological sampling): A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki, A. Asadi, A. Zabihi. Simulation and coding (Geant4-DNA modeling): A. Farhadi, A. Zabihi. Data analysis and interpretation: A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Drafting of the manuscript: A. Farhadi. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors. Statistical analysis: A. Farhadi, A. Abdolmaleki, F. Zolfagharpour. Supervision: F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Accountability: All authors had full access to the data and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this study provided by the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (grant number: 1400/5109/13/D). No artificial intelligence was used.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. Concept and design: A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Data acquisition (physics experiments, rat irradiation, dosimetry, biological sampling): A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki, A. Asadi, A. Zabihi. Simulation and coding (Geant4-DNA modeling): A. Farhadi, A. Zabihi. Data analysis and interpretation: A. Farhadi, F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Drafting of the manuscript: A. Farhadi. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors. Statistical analysis: A. Farhadi, A. Abdolmaleki, F. Zolfagharpour. Supervision: F. Zolfagharpour, A. Abdolmaleki. Accountability: All authors had full access to the data and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this study provided by the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (grant number: 1400/5109/13/D). No artificial intelligence was used.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Reproductive Andrology

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |